Death of a Virgin

by Jennifer Falkner

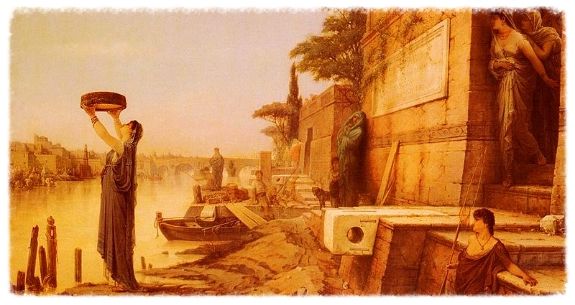

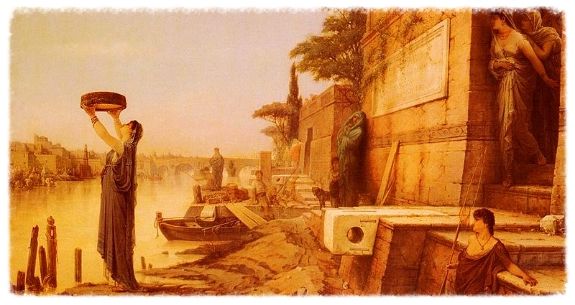

Rome, 44 AD

The shrill scream streamed down the hall and into my room, causing the slave who was braiding my hair to give it a hard, unintentional tug as she jumped.

It was the first of March, the day of the traditional re-lighting of the sacred flame to mark the new year and Thetis was helping me weave the elaborately braided crown of false hair into my own, the traditional style for a Vestal Virgin on parade, a style which took hours to achieve. I was remembering the first time I was having my hair arranged in this way. Nine years old and full of pride at being selected as an initiate in the service of the goddess Vesta. And terrified of leaving my family for the first time, leaving my brother, my only playmate. Thetis, with a fistful of my own curls, yanked me out of my memory. Vibia burst in just as I was rebuking the slave.

“What is it? Has something else gone missing? Thetis has told me she can't find my hair pins.”

“Oh, Valeria, it's horrible. Cornelia Quinta is dead!” There were traces of tears that had rivered down her cheeks and her voice trembled, but her eyes gleamed with excitement.

“What do you mean dead?”

“Aemilia Cana found her. She went to wake her early this morning, but she --” At this, the poor girl's chin trembled and I could see hysteria was going to triumph over excitement. I handed her over to Thetis' care with instructions to make her some hot borage tea, while I went with hair half-braided to see what was going on.

Aemilia Cana, the Chief Vestal, sat at the foot of Cornelia's bed with the dignified stillness of a statue. I entered softly.

“What happened?”

She gestured with one graceful, ringed hand to Cornelia's head. I took a closer look. Her skin had become an inhuman waxy shade and the blueness of her lips made me shudder. The blankets looked dishevelled and the plain woollen shift she wore at night had bunched around her body and under her arms, as if she had been flailing and tossing in her sleep.

When Aemilia Cana finally spoke, her voice was thick. “There was a wine cup on the floor. It smelt of honey, but just to be certain I gave it to the dog. Poor Argus.”

Poisoned.

“Are you alright, Valeria? You've gone quite grey.”

“Yes, yes, I'm fine. What is to be done?”

“We must continue with the ceremony. And I,” she said, as if trying to summon the strength, “must send word to the emperor. He is returning from Britain this month.”

The death of Cornelia Quinta brought the number of Vestals living in the temple down to six. Traditionally only six virgins are needed to serve the goddess Vesta: two initiates, two performers of prescribed ritual and two senior Vestals to instruct the youngest. Until that summer there had been eight of us, including the Chief Vestal. Two of our most senior Vestals preferred not to leave the security of the temple when their thirty year tenure ended. Who could blame them? To go from being among the most venerated personages in the city to the relative obscurity and dependence of unmarried women thrust back into the arms of a family that thought it had done with them. I certainly wouldn't. But Numeria Publia, a frail, well-meaning old thing, was taken by fever last August, and we became seven.

Now we are six.

The body was removed. I had somehow to put it from my mind. It was the first of March and the sacred flame had to be relit, preparations for the sacrifices to follow still had to be made. Cornelia and I had always shared this duty. Now I took Hortensia Calvina with me as my assistant. She and Vibia Paulina were our youngest members and were only meant to be students for their first ten years as Vestals. Eight years had to be enough. I couldn't do this alone. The three senior Vestals, including Aemilia Cana were suddenly nowhere to be found, and Vibia herself was too emotional to be reliable.

Hortensia Calvina walked close beside me as we were escorted by our eunuch guards through the chilly grey dawn to the circular Temple of Vesta. Modelled on the wooden huts of our Etruscan ancestors, it was made eternal in marble. Already a crowd had gathered in front of the temple steps; it parted politely as we approached. Hortensia leaned in and asked me if I thought it was suicide.

“Whatever makes you say that?”

“Because if it wasn't suicide, then it must be murder, mustn't it? At least, that's what Vibia says. Vibia says that Cornelia Quinta had a lover and they were about to be found out, so rather than be buried alive, she --”

“Killed herself,” I finished. “I think that is highly unlikely. Besides, where would she find the poison?” Cornelia Quinta was possibly the least likely of any of us to have a lover. Her mannish features, blunt and heavy, made one wonder why the fates should form the rest of her as a girl. It is true she did have a gentle, almost musical voice and her every action and gesture was possessed with a delicacy which was not without its attraction, even if it were only cultivated to compensate for the masculinity of her appearance. But Cornelia was so very proper. It was hardly credible that she should find a lover, let alone arrange secret trysts, when she felt it barely appropriate to appear in public outside of the performance of her duties to the goddess. Truth be told, I've seen her completely abashed into an awkward silence when merely addressed by a member of the opposite sex. No, our Cornelia Quinta could not have been on the verge of discovery in the arms of a man. It was impossible.

“Until Aemilia Cana has given us instructions, I think it wise not to discuss the matter at all.”

The relighting of the flame and the sacrifices that followed proceeded well. Since Cornelia and Hortensia were much of a height, and Vestals are heavily veiled in public, I don't think anyone even noticed the last minute replacement. I admit that had been one consideration when I selected Hortensia to assist me over the diminutive Vibia. It would never do to upset the populace and produce all kinds of rumours of heavenly disfavour on an auspicious day. The augurs would never hear the end of it and certainly our movements would be curtailed. Better to wait for Aemilia Cana to give us instructions.

I raised my arms to the sky and prayed to the goddess, while Hortensia expertly relit the flame. Its smoke floated through the vent in the roof. As the expectant hush was relieved by exclamations of joy and general rejoicing, I felt a familiar tremor of pride. I was proud to be able to serve the goddess and the Roman people in this way. They looked to me for assurance of their safety and prosperity. They prayed to me for guidance and succour. For a moment I quite forgot the events of the morning and, caught in the drama of ancient ritual, gazed triumphantly on the crowd. One of the temple slaves led the two white cows to the small stone altar at the foot of the steps. Their throats were quickly slit and Hortensia and I held silver bowls up to their spouting wounds, another offering for the goddess.

Soon it was over and the large fire at the temple steps was roasting the goddess' offering and the afternoon's feast. The acrid smell of burning flesh rose through the cool spring air. Without warning the memory of the morning returned and a lump of bile rose to my mouth. I could imagine in a very short time inhaling the same furls of smoke, this time emanating from a funeral pyre. Fortunately a Vestal's veil can obscure many things.

When we returned, Aemilia Cana solemnly led us into the dining room. She was quiet in a way that checked our own desire for talk. Small fragrant dishes of dainties had been prepared and presented on the two circular tables, a tradition on the sacred day and a contrast to the plainer fare we normally endured. At any other time they would been quickly demolished by our mob of hungry women, but today they remained untouched.

The Chief Vestal spoke. The thickness in her voice from this morning had been washed away, replaced by grim determination. “I have received word from the emperor.” That got our attention. Even Hortensia and Vibia, who had been eyeing the fragrant dainties on plates, looked up sharply. The emperor was also by virtue of his office the Pontifex Maximus and as such bore the responsibility for the priestesses of Vesta. Replacing our fathers, he was our sole earthly authority. “He is on his way home from the campaign in Britain and has already re-entered Italy. He is concerned and deeply saddened by the death of our sister, Cornelia Quinta. He is also concerned by the possible ramifications of her death. If it was accidental, he would like to know and have the possibility of future accidents removed. If it was suicide, he would like to know that as well.”

“What if it was murder?” Of course, it was Vibia who had piped up. Aemilia Cana stared hard at the girl, who wilted only slightly under her glare.

“Do you have reason to believe it was murder, Vibia Paulina?”

Vibia shook her head mutely.

“Well then I would thank you not to add the possibility of scandal to our personal tragedy. We shall all feel the loss of our sister very deeply.” Oh yes, I thought drily, glancing at the two senior Vestals, Fulvia and Laelia, who now whispered together at one end of the far table. Very deeply, I'm sure.

Aemilia Cana did not stay to eat with us. Which was just as well, considering the gossip the others girls were dying to indulge in before the emperor's arrival.

“Herminius Gallus returned today,” announced Vibia, her blue eyes gleaming.

“How do you know?” I couldn't help asking.

“Thetis said her sister saw him in the Forum.”

“Do you think there is any truth in the rumour?” Hortensia said.

“You mean, him and Cornelia? I should hardly think so. But then, it is a bit of a coincidence that he should have returned today. Or possibly late last night.”

“That's quite enough, Vibia.” I couldn't keep the sharpness out of my tone. Hortensia's eyes widened, but Vibia simply smirked.

“You're quite right. We wouldn't want such evil tales polluting the ears of Aemilia Cana's favourite, would we?” Before anyone else could interject, Vibia flounced out of the room.

Laelia leaned in toward me confidentially. “It could be murder though. We shouldn't rule it out.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Don't you remember? Six years ago, when Numeria Publia dropped the lamp containing the sacred flame and the old emperor was furious. He whipped her. The old pervert. It happened right here, in this room.”

How could I not remember? It had been a horrific sight. He attacked the poor woman with the beaded leather whip used on slaves and criminals, spittle flying out of his mouth. His eyes glittered with perverse excitement. At least the current emperor, Claudius, with his stammer and his limp, seems, if not harmless, at least less ruthless. Quietly exiling criminals to the furthest reaches of the empire seems more his style. Like Augustus sending Ovid to Tomis on the Black Sea.

“What's that got to do with Cornelia?”

“Why, she informed on Numeria. Aemilia Cana wanted to cover up the mistake. It was a private ceremony, nobody needed to know. But that Cornelia was such a stickler for doing things by the book. Didn't want the improper observance of ritual to anger the goddess and endanger the city, or some such nonsense. As if the goddess cares about a silly mistake like that. She insisted the ritual be performed again and when Aemilia Cana refused, she informed the emperor. Went right over Aemilia Cana's head. Neither Aemilia Cana nor Fulvia fully forgave her.”

“Are you saying one of them --”

“Shhh. I'm not saying anything. Just that I haven't seen Fulvia Petreia shed a tear. Or look all that surprised when the alarm was sounded this morning for that matter.”

“But she's dotty. She wouldn't --”

“She might. They were very close, Fulvia and Numeria, remember.”

* * *

We Vestals are not so secluded as many would think. Not that we are able to walk freely down the street or attend the more licentious satyr plays on state holidays. But we do have our own special boxes at the Circus, opposite the Imperial boxes. We have our own litters and slaves ready to take us, as long as we return before curfew. Many noble matrons are honoured to have one of our number drink tea with them and their friends in the afternoons. Even attending dinner parties, as long as Aemilia Cana gives her permission, is not unheard of. If a lover were desired, an enterprising Vestal could find a way to manage it. Hortensia's suggestion was perhaps not so far-fetched, if it weren't for considerations of Cornelia Quinta herself. No doubt this is why the punishment for an unchaste Virgin is so severe. Live interment near the Colline Gate. I shudder when I think of it. Being led down rocky steps to a small room dug out of the hill, left with a small amount of food and oil for the lamp, enough to last maybe a day or two. Enough that her judge and jury, the emperor and senators, could pretend they weren't her executioners as well. And then to have the entrance closed up with earth. The small mound would be made smooth so no one could ever tell where the entrance had been. I used to have nightmares of being trapped between earth walls beneath the city, gasping for breath, forgotten.

I had no lover, nor wanted one. These nightmares were not the product of a guilty conscience. But I did regret having to refuse my invitation to dinner at the house of Rufus Calvinus. Calvinus had chosen his wife well and the dinner parties she gave were lavish affairs and often advantageous to their guests in ways they couldn't at first guess at. There was a lot of frivolous conversation, fine food and political back-scratching at these gatherings, and a Vestal properly on the outside of such wheelings and dealings had a fund of amusement provided for her in the antics of others.

There were to be no antics that night. We were still within the nine days of official mourning and the boughs of cypress nailed to our door had not yet begun to wilt. The hush within the walls of the House of the Vestals and the muted sounds without made it difficult to believe there was anything but mourning in all of Rome. I couldn't stand the silence beating on my ears any more. I sought out Aemilia Cana.

I found her in her room, gazing through the narrow window toward the temple, as still and vigilant as the marble statues of previous Chief Vestals that watched over the flame from the long courtyard outside. The flame glimmered palely in the inky darkness. She was perched on the old curule chair. Only a few members of society had the honour of sitting in a curule chair, a symbol of authority; the emperor, consuls, senators, the Chief Vestal. Aemilia Cana had appropriated this one, with its flaking gold paint and faded importance, for personal use after Senator Vibianus, Vibia's father, had donated a new one last year.

“Mother,” I began respectfully, keeping my head bowed, “I seek permission to leave the House of the Vestals.”

“Yes,” she sighed, turning to me. “I expected this. This is about your brother?”

“He hasn't got long left.”

“No, he hasn't. These are special circumstances. Under no other would I allow anyone leave for visiting during the period of official mourning. You may go tomorrow. You will return within two hours and take the plainest of the litters, so you don't draw attention to yourself. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, Aemilia Cana.”

She got up slowly, carefully closed the door I had left open, poured us each a small glass of wine and returned to her seat. Age seemed to have caught up with Aemilia Cana very suddenly. Her hand trembled as she sipped.

“I've just learned that the Emperor has returned to Rome. He is concerned about the current state of affairs and what, if anything, can be done to limit any rumours that could be detrimental to the House of the Goddess. I would like you to come with me to the Palatine the day after tomorrow.”

“Me?”

She looked hard at me. “You've always been a bright girl. Level-headed. I'm sure your contribution would be welcome. And,” she said, softening, “you've been such a comfort to me since Numeria Publia was taken from us last summer.”

I was speechless. I had been invited to a private consultation with the Emperor himself.

* * *

* * *

My mother held herself stiffly, as if she could repel any intrusive word or touch simply by the stillness of her posture. Her voice at first sounded forced, but even that could not disguise its soft, vaguely musical cadence. I noticed that despite the official period of mourning after Cornelia's death and the precarious fortunes of the family at the moment, my mother had not neglected the elegantly styled and absurdly tall wig that was the height of fashion just now. Her make-up was also flawless, her green eyes outlined in kohl with a steady hand, her face properly paled with white lead. As if being perfectly coiffed could stave off disaster.

“Have you seen him? How is he?” Her body barely moved as she reached forward and tightly grasped my hand.

“Not yet. I'll visit him after I leave here. I wanted to see you first.”

“Yes,” she said absently. “Yes, that's nice of you, dear. I'll send a basket with you, some bread and sausage. He loves my Lucanian sausage. Do you have any news?”

“I do. Because the city is in official mourning, no executions can take place for nine days. We have some time.”

She allowed a ripple of relief to lighten her features before they hardened again, this time with resentment. “My poor boy. And what did he do to deserve this? Merely quash a rebellion of dirty barbarians and save Roman lives. This is how Rome thanks him.”

“It wasn't quite like that, mother.” I tried to correct her gently, but her attitude was beginning to irritate me. Titus was no more a hero of Rome than I was. Heroism does not run in our family, I think. Though I would like to think there was a streak of pragmatism in there instead.

My brother, Titus Valerius Fulvius, always had an uneasy relationship with his commander in his posting in Gaul. No doubt his commander distrusted Titus' pragmatism. He would rather get things done, usually by doing them himself, than jump through the necessary bureaucratic hoops. In order to facilitate the delivery of certain necessary supplies, Titus told me he often made deals with the locals. That way they didn't have to wait months for requests and replies to make their way through the official channels. Forms written in triplicate sent to Lugdunum or Rome for approval. In one such deal, he caught wind of an uprising, took some men with him, threw their muscle about in a local tavern, roughed up a few malcontents. It was a small skirmish, as these things go, but the commander, his pride wounded, and possibly more than a little afraid of Titus, had him arrested for insubordination and mutiny. There was only one punishment.

Generally such things are executed with despatch, but my mother has powerful friends. She managed to have Titus brought to Rome, but no more. She couldn't prevent or downgrade his sentence, although she had already spent a fortune on lawyers trying. If only Titus had had a greater respect for protocol, we wouldn't be in this mess.

I stood up and pecked her on the cheek.

“Can't you do something? Run him over in a carriage or something? Isn't that how Vestals achieve pardons for criminals? Can't somebody do something?”

“Mother,” I sighed. “I have to go.”

From my mother's formal and fashionable house on the Esquiline, I turned back toward the Palatine Hill, heading to the Tulllianum prison.

Titus' face had a grey cast, as if part of him had already begun its journey to the underworld. A dusty marble statue, not yet adorned with the garish colour we Romans seem to like so much. I kissed his cheek but it raised no answering colour. He gripped my hand, but, unlike our mother's, his grip was not strong. He clung to my hands as if they could stop his from trembling. Skin hung slackly from his cold fingers.

“I was hoping you would come. Tell me, what is happening?”

“One of the Vestals, Cornelia Quinta, is dead. The city is in mourning, so you have another chance. We've got nine days.” I whispered into his cheek as we embraced. Always mindful of who might be eavesdropping.

“Poor Cornelia. I knew her brother. This is not how things were supposed to turn out, is it? I don't think it's worth it. You should just leave me be.”

“Have you ever heard about anything between Cornelia and Herminius Gallus?”

“No,” he said, surprised. “That would be suicide, wouldn't it? Herminius is far too ambitious for that. Why? Was there something?”

“No. I don't know. It's not important. The important thing is we have another opportunity to get you out of here. Wait for word from me. I'll send it the usual way if I can't visit you myself.”

“Calvinus?”

I nodded. “Don't lose hope.”

“Lollus might need something extra this time.” He gestured to the closed door, behind which I had no doubt the guard was listening to every word he could.

I sighed. More money.

“I'll take care of it. Don't worry. Just wait for a message from me.”

* * *

The following day passed slowly. There was more sun and warmth that we usually had in March and we were all glad of the chance to sit outside in the garden for a few hours after being cooped up in small rooms, made stifling by braziers and smoking lamps, while we waited for the cypress boughs to wilt. Laelia Longina brought out cushions for the stone benches that we used for dining in the summer. The angle of the sun meant that we had to squint at each other but our bodies were gently and evenly warmed. The breeze was soft and sweet, wafting away any lingering plumes from this morning's pyre. I stretched out like a cat and watched from the corner of my eye the industrious spinning of Hortensia and Laelia Longina. By the nimbleness of their fingers and the grace with which they pulled the long thread from the wooden spindle, the difference in their ages seemed to melt away. Vibia was as idle as I was and Fulvia Petreia, our oldest member, was snoring gently in the far corner. But slowly the relief elicited by the sun was overtaken by the needling irritability that had plagued all of us for days.

“How many brothers do you have, Valeria?” Vibia, again.

“Just one. Why?”

“You seem to be visiting him a lot then.”

“What are you talking about, Vibia?” Hortensia seemed to be as tired of Vibia's malicious tongue as I was.

“Nothing. Just that Valeria seems to be going out all the time. All these little trips by herself. We are supposed to be mourning. I don't know why Aemilia Cana allows it.”

“You're just jealous. Your family is quite happy not to receive any visits from you.” She turned back to her spinning.

The sun passed over the tile roof of the peristyle and the caress of the early spring breeze became colder.

* * *

The first thing to go wrong was the litter Aemilia Cana selected. Vibia Paulina had asked permission to dine with Geminus Gallus, who was celebrating his son's return from studies in Athens, and the Chief Vestal had allowed her the use of her own highly decorated litter. Mourning or no, Vibia usually got what she wanted. No doubt she was trying to ferret out any truth to the rumour about Herminius and Cornelia. Another possible complication. Aemilia Cana told me she preferred to travel discreetly, in one of the plain litters that looked like a thousand others in the city. It was quite late and the ban on wheeled traffic within city walls had been lifted for the night. The narrow streets were echoing with the thunderous rumbling of wooden wheels dragged heavily over cobblestones. I kept peering out of the gauzy yellow curtain, hoping to see Titus. He should be somewhere on the Clivus Capitolinus, near the Basilica Julia, which lay between the House of the Vestals and the prison.

“I had a visit from Cornelia's father this morning. He was beside himself, poor man. He thought I had been concealing her illness. As if I would, after the fuss he kicked up the last time she was ill. Do you remember, Valeria?”

“I remember.”

“It was only a bad cold. But only his doctors were good enough, only his slaves could nurse her properly. I had to swear then on the spirits of my ancestors that we would take her to his house if she was ever taken ill again.”

“But there wasn't time.”

He would be looking for Aemilia Cana's trademark litter, with its figures carved in relief and painted and its multicoloured drapery billowing from the windows with each sway of the litter, not this nondescript box. I had to give him some sort of signal. If I could see him.

“No, there wasn't time. I think we're passing the road to his house now. Have there been any more thefts, Valeria?”

“Hortensia mentioned a pair of earrings, and I lost some ivory hair pins the other day.”

“Not the ones I gave you? With the heads of the Graces carved on them?”

“Yes, I'm afraid so.” It was impossible to see anything. The traffic, the unevenly lit street. I didn't even know which side of the street he might be on.

“I hate to say this, but I think we'll have to get rid of Thetis. You girls trust that slave far too much and left temptation in her way. Never trust a Greek.”

“Yes, Aemilia Cana.”

“Are you even listening to me, Valeria?”

We might have already passed him.

“Of course.”

Then, suddenly, there he was.

“Valeria, replace that curtain at once. Do you want all of Rome to know our business?”

I waved a hand quickly, jerkily, in his direction before pulling it in and folding it on my lap. I couldn't be sure he had seen it. All he had to do now was cross in front of the litter before being recaptured by the guards. Oh, they were being patient tonight, I must reward them doubly in the morning. Worth all the jewellery and hair pins in Rome, because when Titus had crossed the path of a Vestal, he would have to be pardoned.

The noise outside increased. There was shouting, a scream. Our litter stopped.

“What is it?” I was anxious now. “What's happened?”

“Ask one of the litter bearers. He would be able to tell you better than I.” Aemilia Cana sounded irritable. I stuck my head out the window, the soft curtain attaching itself disagreeably to my hair.

“Glaucus?”

“There's been an accident, my lady. Someone's been trampled. Some tramp, it looks like.”

Up ahead in the dim light, almost obscured by a crowd of gawkers closing in on the sight, I saw a heap of dirty tunic and over-long hair lying pathetically in the middle of the street. He should be alive, if he was trampled he could be seriously injured, but still alive. Still alive. Why wasn't he moving?

A man was berating the crowd. “What was he doing in the middle of the street like that? Idiot. My horses didn't have time to stop. Wagon rolled right over him. Someone pull him to the side of the road. I have to get a move on or I'll be late with my deliveries.”

Having justified his actions to his own satisfaction, the driver and another man began dragging the body, one on each end, out of the way of the backed-up traffic. I don't remember even leaving the litter, or Aemilia Cana's protestations, though knowing her there must have been many. It was all so improper. I was just there, at his side, holding his dirty face between my hands, trying to wash it with my tears. His torso had an oddly crushed look and his legs were bent at an unnatural angle. He wasn't moving. He didn't breathe.

For a long while, neither did I.

* * *

Someone handed me a beaker. It was warm, steaming. Borage tea. I didn't want it but held on to it anyway. I lacked the thought processes necessary to find a table in order to put it down. Its heat began to scald my palms. There were murmuring voices of a man and a woman on the far side of the room. It was an enormous room, lavishly frescoed. Good acoustics. I recognized one of the voices. My own voice leapt from my throat to accuse her.

“You killed him, Aemilia Cana! You took the wrong litter and you killed him. My brother!”

“I?” Aemilia Cana turned from her interview with the Emperor to look at me. “I did nothing. Perhaps it was you, doing rather more than you should. What was Titus doing on that road?”

I couldn't answer her. Where I thought there was one man, I realized there were two. They were both familiar, one from the coinage and one from countless dinner parties.

The Emperor Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus spoke. “Valeria Fulvia. My friend Rufus Calvinus has told me about some interesting acquaintances of his wife's. Herbalists, some of them. They enjoy a good dinner party, these herbalists, though I can't think I would enjoy a meal as thoroughly if I were sharing a table with them. Would you, Valeria?”

I said nothing. I wondered if I could now sip my tea and not appear rude; I was starting to shiver.

“It was very imaginative of you to have planned for your brother to cross the path of a Vestal this evening in order to achieve his pardon. I'm sorry it didn't work out quite as you hoped.” His voice was gentler than I expected. So different from his predecessors. Tears pricked my eyes and I looked deeper into the brown tea. Small dark flecks, pieces of borage leaves, circled in its murk.

“It wasn't the first attempt, I am given to understand. Was Cornelia Quinta supposed to have crossed paths with him first?”

I said nothing. I couldn't speak.

“She had an unfortunate and, I hope I may say, unplanned reaction to the drug you gave her. Mandrake, wasn't it, Rufus? Enough to make her feel ill and want to return to her father's. Where Titus would be waiting to cross before her litter.” He paused and I looked up. His expression held such sadness.

“And now, what are we going to do with you, Valeria?”

I sighed; it was all finally over.

Vesta would need two new attendants for her flame.

* * *

Jennifer Falkner’s stories have appeared or are forthcoming in

THEMA, The First Line, OneTitle and

Flashquake, among others, and last year she received the Reader's Choice Award from Fiction Fix. She lives in Ottawa with her husband and daughter.

What inspires you to write and keep writing?

The best way I can answer this question is by quoting Kurt Vonnegut. “The arts are not a way of making a living. They are a very human way of making life more bearable. Practicing an art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow, for heaven’s sake. Sing in the shower. Dance to the radio. Tell stories. Write a poem to a friend, even a lousy poem. Do it as well as you possibly can. You will get an enormous reward. You will have created something.”