The Elder Brother Washing His Hands

by Adrian Van Young In the early hours of morning, in the State of Virginia, in the summer of 1862, a light could be seen on a dark staircase as a brother and sister ventured down. The brother’s name was Grady. He was thin and wire-strung. His pale, thin face was crowded with freckles. He went ahead of his sister down the stairs laden with a tangle of her things: valises, petticoats, strops hung with shoes, a leather-bound brace of books. The sister, who was younger, held a candle in a dish, which lit the stairs for only her, and she picked her way down one step at a time lifting the hem of her dress out before her, while the brother, up ahead, had to toe his way down, weaving for balance between the banisters, leaning on one to adjust his load and going blindly on. From a distance she appeared to descend alone, enclosed in a private haze of light, making small sounds of surprise or hesitation when her feet got ahead of her eyesight. Her brother was waiting for her at the bottom in a tight atoll of travel-things.

You walk as if you’re made of glass, the brother called up through the dark to his sister.

So what if I am? she said, concentrating. Leastways I won’t knock my head.

When he had her situated among her things, the brother told the sister he’d return in a minute. Going into the parlor, he left her to wait beneath a huge portrait of their great-grandfather, a pale, whiskered man decked in serge and epaulets who surveyed the front hall with a tragic intensity. The girl made a game out of whipping around to catch the painting unawares, or raising her candle to the height of its chin and turning away in horror.

Devil take you, Grandpappy, she said with a giggle, awaiting her brother’s return.

In the parlor, the brother climbed up on the couch and parted the curtains on the drive. His father and the houseboy Aloysius were loading up the family coach, the young Negro holding a lantern to see by while the father overburdened the luggage train. The brother’s older sister and mother stood near in pale but ill-considered dresses, fanning themselves against the heat like fey refugees of the season in Charleston. The Negro tracked the father at an uncertain distance and his lantern fell short of the axel-tree. The father had to feel the suitcases into place, wrenching them out when they would not fit, cursing Aloysius and vanishing again beneath the raised hood of the train. When he’d found a good geometry he stood, gulping breath, and let his gaze wander up the house’s façade, but the thick parlor curtains had since swayed to and the rest of the windows were blind with night.

Back in the foyer, the brother found the sister peering up at the portrait between her fingers. He put a hand on her shoulder and she startled around with the fingers still raised in front of her face.

Go on outside. It’s safe, he said.

Aren’t you coming?

I ought not to.

What do you mean you oughtn’t?

I can’t.

What do you mean to prove?

He did not answer.

Then where are you fixing to go? she said.

Up north, I guess.

To the war?

No ma’am.

Don’t ma’am me, Grady, she said. I’m a Miss.

He smiled at her pluck and smoothed her hair.

All right, Miss. Around it then. I figured I’d shimmy on by just for fun.

She stared at him intently in the dark of the hall. I do insist you write me, Grady.

I will, he said. I’ll write you silly. Now get out there before you’re stranded.

She took a couple steps towards the door, then turned. What would the rest of them say if they knew?

Nothing good, he said. But you can tell them if you want.

I won’t, she said. But they might ask.

He smiled at her again but did not speak.

What about all my things? she said.

Pa’ll get them, he said.

I’ll ask Aloysius.

No, he said. Ask Pa.

All right.

He opened the door and stood behind it, but she dawdled in the doorway with the candle in her hands.

Did the rest go to fight in the war with Cal?

Cal didn’t go there to fight. He’s a doctor.

Well maybe they’re doctoring too. Helping folks.

I don’t reckon so. He urged her forward. They’ve got enough trouble just helping themselves.

Can niggers be doctors like white folks can?

It’s looking that way, said the brother. We’ll see.

She appeared to consider this for a time. Her face was long and dull with sleep.

Go on, he said. You hear that whistle? You’ll want a window seat on the way out to Auntie’s.

He gently nudged her through the door and she tottered outside with the candle still lit. She looked back once, then twice, over her shoulder, and turned around as if to speak, but a voice called her name and she began to run towards it and her candle extinguished as she ran. A thin reef of smoke hung over the drive. The brother closed the door.

He’d roped a bindle sack full of food and loose matches to the upper brickwork of the hearth. At once he went to fetch it down and rushed through the house with it cocked on his shoulder, the rest of the rooms as dark and still as the stairway and hall had been. As stricken.

He walked outside through the kitchen’s back door to a shrill explosion of cicadas, allowing its springs to bend only so far and muffling the clap of the wood with the sack. Between the kitchen door and the old slave-quarters was a stretch of twenty yards or so and the brother went half-sized through the dark, stopping sometimes on all fours in the grass to investigate the way ahead, his face oddly feral in the haze of moonlight and his spine knuckled up beneath his shirt. Near the slave-quarters, he stopped again while an instance of shadow evolved on the grass. Voices came too growing steadily louder, voices the brother recognized, and five large men emerged from the alley that ran between the shacks. Each of them carried an unlit torch. The brother knew this by the smell of lampoil and the sheen of the wicks in the moon. The men talked back and forth in unhurried tones, though what they said he could not hear. Cyrus nudged Tom and Tom nudged back and carried the motion down to Jim and Jim, at the end, clapped Simon beside him, who muttered, Lawd, lawd, and craned to see Tom. At the back gallery of the house, they stopped. A match was struck and passed among them. One by one the torches fired and hunted along the house’s trellises, showing the woodwork higher up where a Secessionist flag hung limp from the gables. But the brother did not wait to see. He had risen from his crouch and was weaving through the buildings. He turned down the alley where the men had emerged, pursued by the light of the burning porch.

Near the final outbuilding where the property sloped and tended away into limitless trees, the brother saw a figure sitting high on a stump busy with something in its lap. He approached with his hand fumbling at his waist for the knife he’d brought to skin his food.

I know where you going, said the figure.

Who’s that?

Yessuh, it said. I sholly do.

The stump was chest high on the brother and thick, with a bole at its center and squid-like roots. The legs of the figure swung down in his path, scooting the air around. They were shoeless.

Stokely? said the brother.

Yessuh. It’s me.

What you doing crouched up there like a bobcat?

Biding my time, said the figure. Hounddogging. Hate to be the Negro to tell you suh, but in case you ain’t noticed your house is on fire.

I know it, said the brother. I saw them coming.

Well suh, I awful sorry, but yonder she burn.

You still haven’t answered my question, said the brother.

I ain’t got a answer but the one I done told.

The brother picked a match from the box in his bindle and dragged it to life down the side of the tree. Within its flare, the Negro sat, wood-shavings piled in his lap. He’d been whittling.

We a sorrowful whip scarred lot, said Stokely. Can’t blame us much for the houses we burn.

I don’t, said the brother. I believe it’s your time.

Stokely laughed softly. Yessuh. It seem so.

The matched had burned down to the brother’s finger-pads. He shook it dead and let it drop.

So where do you think I’m headed? said the brother.

You on a dark path, Lawd bless you, suh.

And you’re on the path to freedom, I reckon?

Stokely gave a whistle and kicked his legs. Close as I can get, he said.

Well aren’t they the same but dressed up different?

Young Marse got notions of his own, he do.

I’m going where I’m needed, said the brother. And you?

You going where you think you is needed, said Stokely.

And who’s to say I’m not? said the brother.

I know for a fact you ain’t.

They were silent.

Moving on tomorrow, I expect? said the brother.

Moving on something fierce, said Stokely.

Best loot the house before it goes, said the brother.

He could feel the Negro searching out his eyes in the dark.

Yessuh, he said. I’ll pass the word.

Good luck to you, Stokely, he said and reached out.

But the Negro had moved down off the stump and stood out of range of the brother, staring at him. He stared at him a moment more and then he walked away.

The brother walked to Maryland because he knew that the war would be there to greet him. He forsook the state road where his family had gone and where his eldest brother had gone before them, a road that ran north and then forked east up the kindly plateaus at the hem of the mountains, and one that would have brought him across the state line with a minimum of danger. He was for the mountains that would cradle him up to the top of the state as far as Leesburg, and there, at the mouth of the Potomac River, he could follow the fighting north. They were thin and ragged mountains, like the spine of a lizard, and riddled with spruces peak to base. The brother gained a ridge where he crouched chewing bread and watched his birthright smolder in the valley below, the wind drawing huge bloats of smoke up the cut that broke against the base of the mountains. In the blueness of dawn, the fire burned brighter; an island of flame, impossibly orange. He could see figures milling in the field, among the shacks, and within sparking distance of the fire, in three groups. No one there came on with water. Pity the man who would have tried. The last potential water-bearers had quit that place the night before.

Then the brother noticed a trio of figures who were walking away from the fire, right toward him. They were as dark and anonymous as the shrubs that grew downgrade of the ridge where he crouched, and they moved in a processional, one by one, in a manner ceremonial and militant both. He watched them make across the fields and across the plateaus to the mouth of trail, but did not wait to watch them climb for fear of being spotted. He shouldered his bindle, stretched, and went on, up the rock-studded spine of the mountains.

* * *

* * * Night of her birth, a violent storm. Rain sluicing off the eaves, down the gutters. Wind full-throated in the trees. The moon reticent behind the rain like a fortuneteller’s face behind a curtain of beads. Old Negro spirituals carrying up from the glowing doorways of the shacks, contrapuntal to the cries of a difficult labor and the drumline of the falling rain. Then sudden silence among the shacks. Hallelujah’s and Hosannah’s from the birthing room, new clamor. The stooped Negro doctor emerging in his shirtsleeves, treasuring the newborn aloft to the storm.

* * * Roundabout dawn he stopped to rest in a meager plot of grass by the side of the trail. He had not been eating nor had he been drinking in accordance with the strain that his travels took on him, and his decision to rest, just one day out, was one that his flesh had made out of necessity. He fell into slumber so complete it seemed refined of even dreams, and when he awoke in the bright afternoon it was only with considerable effort. But scarcely had he forced his eyes than dust from the trail convulsed them shut. A confusion of horses’ hooves stormed past; he rolled over sneezing to hide his face. When at last he was able to see again, a horseman sat above him, tin-stamped against the sun.

He was one of a company of six, the other five waiting ahead in the trail. He was grizzled, red-eyed, unwashed to negritude. His hat looked like something that had died in the road.

What’s your company?

I’m not enlisted.

Want to be?

No, but I thank you.

All right.

The horseman spit, removed his hat, and clawed his fingers through his hair.

We’re going to rendezvous with Lee. Most of us just joined up this morning. What’s your business round this way if it ain’t with them blue-suited mott-lickers North?

I’m hunting somebody, said the brother.

Blue or grey?

He’s an independent agent.

No such thing these days, said the horseman. Every man’s got to take a side.

Well, technically he’s blue, said the brother. He’s doctoring under McClellan.

How’s that different, to your thinking?

Not much different, I guess. It’s complex.

Sounds pretty simple. Your man’s a backslider.

It’s personal business between him and me.

Well, said the horseman. My offer stands. If you’ve a mind to, you can ride on with us.

The brother nodded sharply. I thank you, but no.

The horseman regarded him for a moment. How are you for food and drink?

I’ve still got a couple of mile’s worth yet.

The horseman grinned and shook his head in a kind of wondrous disbelief. He withdrew his canteen, dislodged the rubber stopper, and reached it to the brother, who nodded his thanks.

Good luck to you, then, said the horseman, while he drank. I’ll commend your stupidity on to the General.

The brother stopped the canteen and handed it up. I’ll commend it to him myself, if I see him.

Long live the south, said the horseman.

All right.

And long live brothers of the cause. The horseman gave pause. Are you at least one of those?

I’d be hard-put to decide just yet.

Well, come on to Maryland when you do. We’ll skewer some Union boys together.

He tipped his hat, toed his mount and rode double-time to gain his fellows, who were now advancing in single-file along the bluffs to the east.

The brother surveyed the country round. His legs had done well for him thus far. The staggered rock-faces, the spruce-choked gulleys, and the narrow mountain passes of the land he had crossed, looked ugly and fierce, inconceivably treacherous. Yet there were the figures, ranked and solemn, sure-footed as goats on the lower escarpment, making across the ground he’d covered with a grace that suggested their feet never touched. A family of Negroes who had not stayed to watch their prison fall to ashes, or perhaps refugees from the languishing guard, old knights of the South who had traded their linen for a penitent’s cloth befitting the hour. And the brother could see now it was day that they were cowled from head to toe, and that the one in the middle was shorter than the others, its vestments dragging on the ground. They seemed to be walking in remembrance of something, though what this was he could not say.

I see you, the brother said. Can whoever it is you are see me?

* * * Congruent upbringings, his and hers. He in the house, and she in the shacks. Butterfly chases and firefly hunts throughout the milder of the seasons, he among the trellised bougainvillia and wisteria, she among the kudzu and the weeds between the shacks. Mason jars and corkboard squares, perched in like arrangements on their windowsills and bedsteads. She of the explosive hair, skin cooked smooth like exposed saddle-leather. He of the cowlick, unaccustomed white hands, well-fed rolls above the belt. Aunt Berenice, his soft Negro Mammy, making out the limits of his play on the lawn. Sometimes Margaret with him too, driving her shadow abreast of his, while Cal sat collected and strange on the porch, learning his anatomy. She with her mother Antoinette in whatever hours the woman was afforded for this office, her little brother Stokely capering through the tall grass, clapping his small cushioned hands. Hemispheres aligned but separate. The old questions mounting between them like song. One light, one dark, observing each other, across a field of nascent cotton.

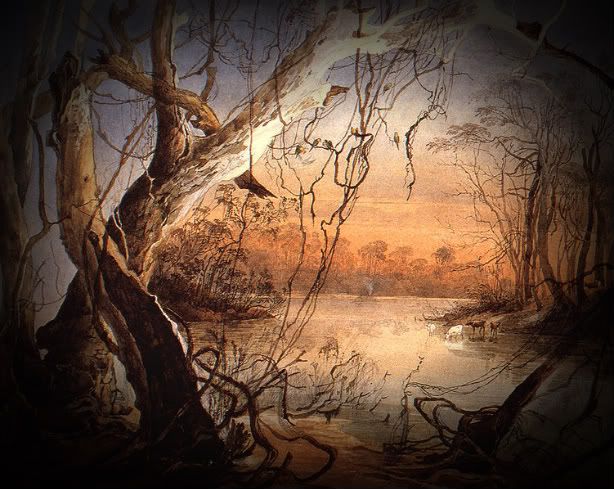

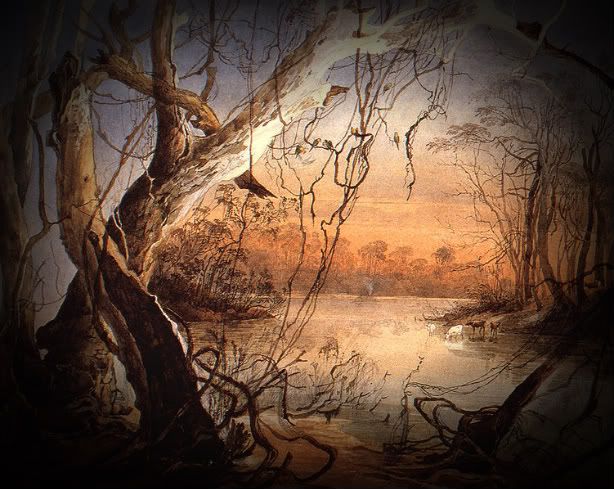

* * * That night he came into a dry, wooded valley that lay in the void between two mountains. A place where the moonlight could not reach, and by the look of it, the sunlight neither, for the trees were arthritic, the shrubs desiccated, the ground as featureless as a pan. Mindful of the local character, he found himself drawing in shallower breaths. The trees were more tangled the further he went, growing all which ways but up, and in the absence of moonlight a soft phosphorescence seemed to radiate from the ground itself. Up ahead, a sort of throne made by two embroidered oaks, from the low boughs of which hung a cast-off robe that the brother only noticed when it brushed along his forearm. He stopped in the darkness, fingered the robe, and made to pass between the trees, but the voice of a woman spoke his name from the black recesses of the throne. He froze.

Grady Earl Coontz, the strange voice said. Rest your bones a while with me.

Show yourself, he said. Who’s there? I’ve got a knife here, and it’s needing some work.

Now the voice did not respond. He approached the wooden throne with his knife at the ready. An ancient woman sat cross-legged, faintly luminous, like an idol in a niche. She was totally nude, very pale in the ground-light. Withered paps and ropy arms. White hair parted either side of her face like a thicket she’d emerged from. Behind her long and knotty head, a colossal armature of spine, as if she possessed the bone structure to fly great wings now shorn from her body. A foul archangel cursed to walk, or was he cursed to walk with her.

He asked the canopy above him, Am I asleep by any chance?

But the woman was real, for the woman was speaking.

The Vengeful are ugly, in thought and in deed. Share we this, in spite of age, in spite of origin and sex, in spite of sundry opposites that present circumstances vex, and thus am I disposed this night to speak to you of what may come that you might come yourself, and soon, to curse the day or see it won. For Vengefulness will take you far, from mountains high to valleys low, through heat unholier than hell’s and darkness darker yet than death, across doldrums where no winds blow, and through limbos of life bereft. Despite dead men laid in your path, and war-scarred regions in your wake, where fires burn and structures lean such as the fire could not break. Against the omens of we three, your vengefulness will drive its prow, and trammel too your soul’s unease, or such of it you will allow. But be you vehicle of hate, or architect of just design, I cannot say, for know I not. This shall you yourself define.

You could just as well save me the trouble, he said. Or the headache of listening to you, at that. He scrubbed at his face with his palms and stepped back. Now I’m going to blink my eyes.

When he opened his eyes, the hag was gone. Likewise the tree-branch of her robe. He was crouched absurdly in the alcove, scarring the wood of the tree, like a lover, when suddenly the moon appeared to show him where he was.

* * * He walked through the night and through the coolness of the morning until the land greened and then leveled out, and he slept off the hottest of the day in a sheltering thicket of spruce, undreaming. He woke as the last of the afternoon sun was threading itself between the trees, and rose with the sweat still drying on his face. Leaves and dirt clinging to his cheeks. Sore feet. He ate a bleak sandwich of white bread and chocolate, rationing sips from his canteen to chase it.

On a ledge of limestone by the side of the trail he stood to watch the sun’s decline, and the valley below seemed a volcanic waste in the brilliance of the moment when it dropped behind the hills. Going across the lower climes was the band of pursuers diminished by one; a twosome now, one tall and one short, their staggered shadows gliding across the rocks and stretching out in front of them like taller, leaner selves. The hag was no longer among them, it seemed, if hag there had ever been at all, for when the brother tried to fasten on last night’s events they seemed more plausibly ones he had dreamed. And indeed, sometimes, the figures wavered, grew closer to him and then more distant, seemed solid enough to block the light that wrought their shadows on the ground and yet other times seemed shadows themselves, projected up slant from the earth of their making. He wondered again if they were real and then he wondered did it matter.

I’ll be waiting for you, the brother said. A few pebbles skittered down the grade; he had kicked them. I’ll be waiting for you. He was shouting it now. The cliffs to either side pitched his voice back.

* * *

* * * Tragedy in his fourteenth year when his Bay, Thurgood, tore a hole in the fence, half-disembowling itself in the process. The ragged edges of its belly where it had failed to clear the jump. Eyes rolling white and muzzle frothing for him to deliver it peace. But he could not. Him sitting down among the leakage, smoothing its fearful ears flush, crooning to it. She emerging from the shacks, not eleven years old, but attuned to his misery. A harrow cradled in her arms, sharp edge shining down the furrows. ‘Are you all right?’ ‘My horse is done for.’ ‘I can see that, but are you all right?’ Now she was there, he was, and he said so. Inordinate beauty for just one soul. Hair a mist above her head, copper in the afternoon. Her eyes seeing him and yet through him at once. ‘I brought this here for you. He’s hurting.’ ‘I don’t think I can do what you’re saying I should.’ ‘You’ve got to do it. It’s only what’s right.’ ‘I know,’ he said, ‘but I can’t.’ ‘ Then I’ll help you.’ Handing him the harrow. ‘On the count of three,’ she said. ‘Maybe the count of ten.’ ‘No, three. You’re not the one losing blood by the quartful.’ ‘How old are you?’ ‘I’m twelve,’ she said. ‘You’re keen for twelve.’ ‘So I’ve been told.’ Eyes meeting for an instant, then shying away. ‘Where am I supposed to strike?’ ‘Right about here,’ she said. The horse’s temple. Skin twitching gently with the soft engine of it. He brained the horse quickly, and it lay still. ‘That was even harder than I thought it would be.’ ‘But you did it,’ she said, ‘And now it’s done.’ ‘What’s your name?’ he said. ‘It’s June.’ ‘I’m Grady,’ he said. ‘I know your name.’ ‘Well, now we know each other’s.’ ‘So we do.’ And he was hers.

* * * In the higher altitudes, things greened. Creepers, kudzu, weeping willows, Japanese wisteria. It was the middle of the night but it might have been noon for all the unique smells and birdcall. Lilies-of-the-valley by the side of the trail like diminutive ghosts in the moonlit haze, not unlike the ground-fog in the valley of the hag, but with something frenetic, unhealthy, unnatural. Hares and foxes streaked the path. Owls interrogated from on high, looking famished. Rodents tunneled through the bramble, fleeing from death on the wing.

After a while he came into a clearing which was just a slim crescent among the trees. At the opposite end, with its back to him, a figure rooted in the dirt. About the size of a child were it not for its head, which was, at a glance, twice the size of his own. It appeared to be digging something up, digging something under, or maybe just digging. The muscles of its naked back were dense and electric with strain.

The figure noticed him, and turned. An odd feral jerking of the head, waist twisting, hands curled up at the chest, like a lizard’s. He thought that it would spit at him but then it drew upright.

The child stared at him for a time. The brother stared back, a bit sick in his stomach. Its head was so huge that it might have belonged to a heftier child who now went around headless. Below the neck it was hairless, and below the waist sexless, with thin, double-jointed-looking legs, like a foal’s. Its eyes were coin-sized pools of black without any iris to speak of.

The thing made a dash for a nearby tree and scurried up among the boughs. It took up a crouch, staring down the brother, with its long toes twisted around the branch. The mouth in its face, when it opened to speak, was a perfectly black and toothless hole.

I was never born, but am. And I follow on the heels of the Vengeful, for she made me.

Well, I’m sorry to hear that, said the brother, and started to approach the tree, but the child disappeared in a chaos of leaves and emerged through a parting five feet higher up.

Vengefulness will take you far and long sustain you with its heat. So far have you come, Young Coontz, and two of us yet chanced to meet. But Vengeance is a second savored, perpetrated in half that, so weigh you carefully its merits before you serve it, tit for tat. But alas where Vengefulness propels, Vengeance must needs issue forth, so who are we, mere agents three, to reroute you upon your course? Which brings us to the hour of Vengeance, verily, an hour of death, though in your case, midst war and waste, death, like blood, will call to death. Indeed, Vengeance may warp and pale, as I have warped and paled myself, though hasten judgment must we not, humble agents three, one less. And yet less two, now I have spoke; our last remaining minion comes. Recognize his face will you by the fact that he has none.

Slowly, the brother shook his head. His palms, outstretched, began to tremble. And then with a howl of disbelief that had the while been boiling in him, he ran to the base of the tree, where he stopped. The child’s face was gone and the canopy dark. There was only a tossing of shadowy boughs to suggest it had been there at all.

* * * Through the following day, a poisonous heat. Mirages of water and shade on the trail. Gnats and mosquitoes, in the nighttime voracious, wallowing by in disinterested arcs. Every half-mile the brother stopped to wipe off the sweat from his brow with his shirtfront. He had taken to turning around when he did this to count the miles that he had come, although he had promised himself before leaving that this was a thing he would not do. But he stopped to count the miles regardless, subtracting them from the miles ahead, and found that he was either too close to the war, or too far from home to turn back.

He went along a mountain pass where there was barely room to walk. The trail spiraled upwards, and then funneled down, as if undecided which way it should tend. Going around another bend, a pair of feet resting in the middle of the trail. On closer inspection it was one of the company that the brother had encountered on his second day out, and this ragged stranger dead for days, with none but the flies grouped there in remembrance. The man’s leg was swollen to outlandish dimensions; suggestive, he thought, of an untended wound, or a run-in with a deadly snake. There were coins upon his sightless eyes, though one of them slightly less in value, as if those who he rode with had emptied their pockets, unable to find two coins the same. The brother read the man’s name-tag. Ennis McHolister Sage, it said.

The corkscrew passage channeled straight at what the brother judged to be the summit of the ranges, and now the sun was cooking into twilight below, he stopped for a while to feel the breeze on his face. The last and tallest of the figures was making up the grade behind him with a slow and effortless locomotion, with nothing whatsoever of the clumsiness of man. Its black robe fluttered out behind it with such voluminosity it might have been wings, or a dark ectoplasm that it labored at the center of, bearing it up against gravity’s custom.

The brother hailed the figure. Ho, there. It did not waver. Ho, there, he repeated, you laggard spook. But then it was lost to the hills.

He went on.

* * * From Thurgood’s death onward, contrary polarities. He fascinated, then enraptured by her, this siren of the garden hanging laundry out to dry, or by the river of an evening with the other washerwomen as they slapped out the bedding from soaking to damp. No rest for these laundresses, these shiners of brass, these fillers of decanters and platers of meals; no more than there was for the lovesick, this boy, crouched in the thicket for a fleetness of thigh, or the quiver of a backside through the cloth of a dress. ‘Hello June,’ he would say. ‘Massah Grady,’ she would answer. ‘Your hair looks powerful fine in braids.’ ‘I thank you, Massah.’ ‘No need. And it’s Grady.’ ‘Well, I thank you Massah. Most girls got braids.’ ‘Not like yours, they don’t,’ he said. Days of her kneeling in the garden, skirts hitched up past her knees while she weeded. Nights of her passing through the rooms, on this or that errand in the hours before sleep, when the fires stretched their spines on the manicured hearths and the kerosene lamps burned low in their niches. Cal taking notice along with him much to the detriment of his studies, and the two brothers rising from their chairs, or craning around where they stood to observe her, or shadowing her, even, at the minutest distance, as if they themselves were unaware of desiring her, for they often found themselves within an inch of her person, mutually blind as to how they had got there, or wherefore they had been propelled, knowing only that here was a creature to contemplate, and with her, a whole way of life. Cal putting down his anatomy book and sliding his pince-nez down his nose, the same two motions every evening and to think the brother noticed neither. June pretending not to see, but not unwelcome to it, either, this awkward, foolish, forthright passion that Cal had conceived for the house nigger’s daughter, and one that he planned to see out to its end, little had the brother known. And then when Chestnut hit Fort Sumter and Cal suited blue as he’d promised he would, the younger brother ran to find him, wanting to ask him was he scared, wanting, again, to hear his reasons why he would not fight for Dixie, even though he knew that Cal would never fire a musket but was looking to tend to those that did, so that he, in a way, was the loftier hero, in his very disdain for such gory romance. Not just Cal he found, however, bursting unannounced into the parlor off the kitchen, having searched every inch of the house and the grounds and this the one place he’d not looked. Hair, her hair, pressing under the shelf where the sacks of biscuit flour were lined, and Cal was driving up inside her, using the backs of her shoulders for leverage. Even worse, the brother felt, was that he could not see her face. In the moment their crisis came upon them Cal clapped his hand over her mouth, and with the other one wrapped around her stomach, guided her through their cycling down. The brother watching them with such immense force of feeling that gradually they turned around. But the brother had gone—was out walking the fields, and walking through the bloody cotton, with the image of their violent coupling returning to gall him again and again. There in the drive when he got back, his brother’s midnight coach departing, and nothing from Cal in the way of farewell but what he had seen in the parlor that night. Figures at the edge of the slave barracks, watching, murmuring among themselves.

* * * Along the northern ridges, long views of the country. Forsaken tracts of farmland, grotesquely overgrown. Wooden plows appointed to stand in the corn like pointless contraptions of torture. Along an isthmus of rock, the brother crept, looking to the west for any sign of recent life. Pebbles trickling down the grade, the rough, corroded sound of his breath in his throat and now a dry wind among the birch-boughs were the only natural sounds in hearing. Soon the air grew clogged with smoke that densened and darkened down the valley, and suggested low fires that could not be seen for the sheer amount of it they spewed, so that the smoke appeared, from where he stood, to be emanating from the earth itself, as if the Negroes and the Yanks had gone so far as to set their blazes at its core. What land he could see through rifts in the smoke was vaingloriously ravaged after Carthage or Cannae, with the furrows tossed and leveled, and in places scorched fallow, and with the galleried houses and outbuildings chewed and ransacked to their girders. Even the gaunt, sporadic slums that leaned from the hills surrounding the houses had been met with the same itinerant violence. And not a soul in sight.

A night to redefine the word. Black and still beyond all reckoning. So dark, in fact, that he began to disbelieve in the world he had witnessed by daylight. Branches, shrubs, and hanging moss made a gauntlet of the trail, but the brother tore free of their claws and loped on without nothing but his fear to guide him.

Then he passed a curious shape. At first he took it for a birch with uncommonly white, reflective skin, but then he saw there was no moon, so how could it be shining? On closer inspection, it was a man, standing idly in his path. Or maybe not idly, the brother considered, for the man was too still to have no purpose, but seemed to be awaiting the arrival of something, there in the limitless dark. To make matters stranger, he appeared to be blind, for he did not mark the brother coming, and stood with an aspect of blindness about him, listing slightly to one side.

Grady Earl Coontz, he said, without affect. Come and stand a while with me.

You’re number three, I expect? said the brother.

Indeed, said the man, with a nod. I am he.

He was in a sorry state of nature. Piebald chest and withered shanks. And as the brother drew closer, he was chilled to discover that the pale stranger’s face was entirely featureless. While the body was that of an ancient man, with its collapsed musculature and general gauntness, the face was like a wall of gauze; he could scarcely imagine where the voice was coming from. The horrid figure’s cast-off robe had been spread on the ground beneath its feet, and here he stood, as on a dais, suspended in the element around him.

Where Vengefulness will drive you long, and Vengeance satiate your gall, it is I, the Avenged, at cycle’s end, who shows withal an inkless page, upon whose regions yet are writ the dicta of one damned or saved. For the Avenged, his hatred slaked, or thirsting still within his breast, may live to see his enemy against all odds become a friend. But lo for pride he will see lost a part of him to which blood beats, and taste of his hypocrisy with all nature imparts, one less. The path remaining wants your toe. Or else the path behind your heel. Give it fore or aft, young Coontz. Smear the wax or the plant the seal.

The man passed a hand over its face to illustrate the blankness there, and the shadow of its fingers rippled and raked an instant behind the hand that made it.

At once the forest bloomed with moonlight. Footlamps reigniting on a vaudeville stage. The trees revealed themselves as such, then the shrubs and hanging moss. The man without a face was gone, though where the brother could not guess, for certainly one so strange as he had no way to live among men unmolested; materializing, prophesying, standing naked in the dark, preceded always by the hag and the malformed child—for him the brother felt, unexpectedly, a kind of misdirected pity; but none, contrarily, for himself, because what was he doing standing here with so many miles yet to cover? But he stood there for a good while longer, pivoting dreamily in the glade, wondering not what he should do, but how he should go about doing it.

* * * First weeks of Cal’s absence, the summer in earnest. The bushes releasing their berries, all skin. Lovesickness, boredom, and bitter frustration became for him states cooked down by heat into one paranoid master-state, and caused him to appear to lurk even in places natural for him to be in. She hurrying through the fog of his stare, sometimes with a frank disgust, so that occasionally he would order her to clean or mend things just to hear her acquiesce. In the meanwhile came letters she could not read, but that she got the old doctor to read aloud to her, and then in the halting, emotionless tone of one accustomed only to reading prescriptions and procedurals from outdated medical books so that the elder’s account of doctoring for McClellan had all the impact of a Sunday school pamphlet. Nothing the doctor had said or inflected, hopeless as he was at imparting a subtext, but through a certain over-length in the telling of events and the way their author tried to parse them, rationally, surgically, inside and out, with a poverty of likeness that haunted the diction. The younger one starting to intercept, first experimentally, then as a rule. As glad of the elder’s pronouncements of love as he was of the hardship and trauma of war, because he could not decide which brought him more pleasure, to feel his hatred justified or to know his older brother suffered, and since the letters dealt in both, he read and reread them again and again. And abusing those letters more practically now, not for their content but places of origin, plotting the postmaster’s seal from each city in between predictions from the Herald in town, and when he could get it, The Richmond Dispatch, as to which way the tide of war would presently pitch its bulk, and when. These latter marks with headless pins, the former with ones tipped black to mean certainty. Courses emerging like spirit-trails across the map’s contested regions. But which to take, he agonized, for a course once taken would be set, and he knew this. Across the Appalachians to collide with Lee’s army, or around the base of them to melt in with Hood’s? Then one day while she stood washing dishes at the big metal sink that abutted the scullery he crept up behind her on hasty feet, wrapped his arms around her waist and buried his nose in her hair. ‘Nom, Massah Grady. Ain’t what you think. Ease off now,’ she said, ‘Ease back.’ But him clinging to her, absorbing her smell, such a rare, garden smell, but also mammalian. He could not remove his poor, drunk nose from the hair at the base of her skull. So she levered herself around to face him and launched from the sink to drive him back, shouting at him, ‘Off. Get off, I said.’ Which was left reverberating in the kitchen. Releasing her startled, ashamed, enraged. Walking from the kitchen towards a place where she wasn’t, but no place existed, he found soon enough. Stumbling around for the rest of the day, he forgot to intercept the mail, and with it a letter from his brother, the fifth unanswered of its kind, calling for her to quit the house and join him in Kentucky.

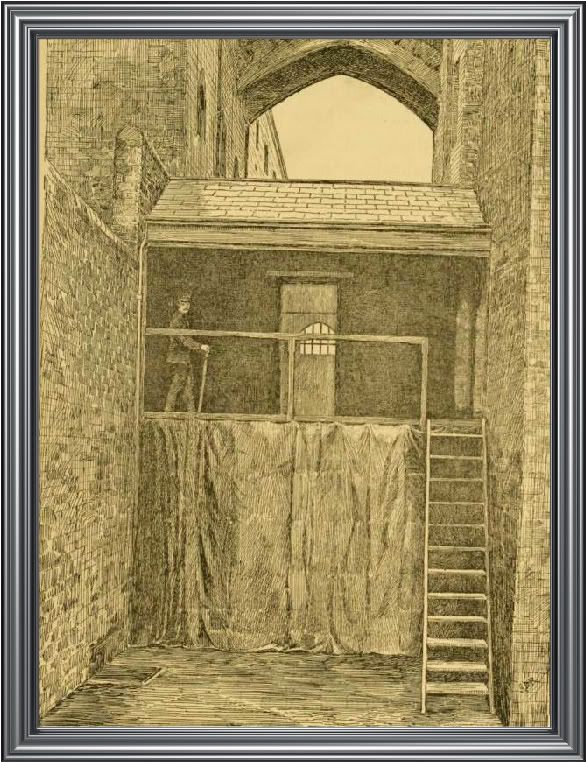

* * * The brother reached Sharpsburg just after dawn, on the fourteenth day of his journey. The woods outside the town were hung with smoke and the murderous percussion of cannons and muskets could be heard in the cornfield beyond. Only where the woods began to thin, did the brother first encounter the fallen. They lay in the dirt in grim disarray, blue coats and grey coats alike, unbreathing. Some of them prone, and others upright, and yet others still who sat slumped against trees in an audience of wordless sorrow. He found no living soul among them. Muskets and cavalry swords lay strewn. He availed himself of a stray Enfield and began to creep around the corn. He watched a Union volley and a Rebel response, hasty and smoke-blinded shots to the man. The battled was divided into narrow vignettes between the spaces in the trees as he passed along the field, and not until a ball chewed into an oak after shaving along his hairless cheek did the brother come back to himself and remember the bedlam in which he’d fetched up. He found he could not fathom such a simple contention resolving itself in such chaos, but lo. Gaps opened up along both lines after another reciprocal volley and men knelt silently in the dirt and pitched face-first out of formation, while the horses of the cavalries reared and plunged, trying to buck their cursing riders. Cannonballs also broke the lines, atomizing some and raining dirt upon others, while the officers aft of these unlucky few steered their horses round the flank and glassed the field to count the fallen. The center of the field was a smoky limbo where only the stubble of cornstalks remained.

Then, up ahead of him, small drama. Two boys tussling in the leaves. One of them blue, brass-buttoned, bugle-hatted, with a rusty blue sash around his waist, and the other one not grey, per se, but clearly allied with the stripe of that army, for the rags that he wore had been leached of their color like the grave cerements of a beggar. They were strangely isolated from the battle at large, in a glade where the sun filtered down among the trees, and the brother crouched down to watch their struggle with a look of scientific curiosity. Too close to charge muskets and fire with any accuracy, they had opted for their bayonets, and were currently locked in an awkward seesaw with the bores of the muskets pitted tensely together, their boyish arms shaking with the strain of the impasse, and their dirty faces twisted up. Trading curses back and forth as to which would be off to the Summerland first. But if either of them knew what the other one threatened, the brother would be damned—they were children. The Yankee boy slipped in a silk of pine needles and the Reb, caught off balance, slipped forward in turn, whereon the blade of the latter sank into the former, and he fell with the gun sticking out of his gut. But owing to the suddenness of his kill, the Reb fell forward along with him, and after a moment of dangling high in a pantomime of schoolboy antics, the Reb let go of the butt of his gun, and pitched over backwards with a startled expression. In the following silence, while the Union boy died, both of them sat in the dirt.

By the time he reached the Union line, his ears were ringing something awful. No one paid him any mind, Confederate though he might have been, as if any man mad enough to reconnoiter with such a traffic of lead in the air as there was would have neither the wits nor wherewithal to sabotage their camp. He passed along the rampart with his commandeered gun like a child in a spirit photograph, and as silent, while all around him muskets flashed and men fell down the whole field over. Since there was little correspondence between shots fired and men who fell before the shots, death was occurring in no right pattern, and the skirmish seemed happen much slower than it did. A cannonball carved a long fatal valley into the Union’s western flank, and a bright red mist hung there for a time while soldiers in the area yelped, took cover, dusted off bits of their brethren and marched. But a survivor broke rank running forward with his musket in a fog of violence so intense that he scarcely resembled a man any longer with his mouth twisted wide, his dark eyes agog and his limbs swinging crazily all which ways, yet stopped in his charge when he saw, looking down, that one of his legs had deserted him. He he fell beneath his comrades’ boots, who passed over him with indifference, and marched. Meanwhile a Reb on the opposite side veered like a drunk amidst the smoke while his fellows tried to pass him to the margins of the battle for the piece of shrapnel lodged in his neck, but they could not. Like the Yank without a leg, he was cordially trampled, and the brother could not see what happened to him after that. And in the meantime Rebs and Yanks alike were picked apart slowly by minie balls until they were all but racks of bone to which sinew and vitals clung, left there to teeter among the scorched corn like mutilated scarecrows.

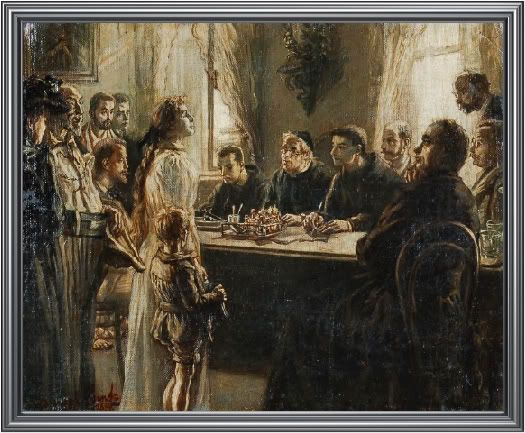

Then behind the breastworks, off among some trees, the brother saw a medic’s tent. There were men queued up for fifteen yards to gain admittance at the flap, some of them clipped of arms or legs, or bleeding from the ears, or disfigured by shrapnel. For every man who went inside there were three carried out by the feet, or on stretchers, most of them dead and others close to it who gibbered old names that no one knew, or tried to make their peace with God. The brother sat against a spruce with the musket bridged over his knees and waited. After a while he took up the gun and started to load it as best as he recalled. He cloth-wrapped the cartridge and jimmied it down, once and then two times, with the ramrod; he pressed the primer into place, then dusted the barrel and breach with gunpowder. He hefted the gun and drew a bead on an adolescent bugler to the left of the tent, but when the boy walked out of range he propped it stock-first in the ground at his feet.

A man in a bloody surgeon’s apron parted the flap of the tent and stepped out to direct the flow of traffic inward. The brother stared intently at this man, who was distant. He reassessed his weapon’s readiness. The man had the same thin face as the brother, but ending in a long and imperious chin, and the same ropy muscles as him too but less haphazard and twisted together. He made more sense in his skin overall. His apron was dyed to the hem with blood and he held in his right hand a bright bonesaw that he absently started to gesture with, indicating to a corporal where the dead men should go, where the fatally wounded, where the barely intact, three different camps up ahead in the trees that were staffed, the brother saw, by yet other surgeons. The corporal nodded at him and the man spoke onward. The corporal seemed to hang on his every word. When the man was done speaking they just stood there and regarded one another through the thick drifts of smoke, their worn, dirty figures hunched in on themselves, and their faces very pale.

The brother drew a bead on the man in the apron. He cocked the hammer into readiness. His hands began to shake, which made the muzzle waver. He sat it in the dirt and raised it again.

Goddamn you, you meddling spooks. He canted his aim to the left, and fired.

The shot spent wide of the man in the apron and a puncture wound opened in the canvas of the tent. The man in the apron looked wildly about him but the brother was hidden among the trees, and the corporal, who was halfway in front of the man as if to take the bullet for him, had instinctively drawn his long carbine and described the clearing with it. The brother reloaded without meaning to. It was all he could think to do at the moment. The corporal advanced across the grass to see about this hidden scout.

A pretty Negro woman came out of the tent and reached awkwardly for the man in the apron. She was wearing an apron herself, just as bloody; her hair was tied up in an old ragged scarf. The woman reached and reached again, a frail, stunted motion, like the gathering of air, but no matter how close she got to the man, no matter how wide she spread her arms, it was never close or wide enough, as if she were poised on a spindle. Then the brother saw she could not stand, was staggering with the effort to, her arms not level at her sides but clutched around her ribs. She started to fall, past the man in the apron, who turned around and caught her up. He tried to make her stand but she would not. So he laid her in the grass and knelt down above her.

On seeing her, the brother dropped his musket and walked mechanically out from the trees. He walked despite the snooping corporal, who had judged his position from the shot. The man had a Spencer repeating rifle. He riddled the brother’s whole left side. The brother veered crazily on his path and fell into the thin, scorched grass. He stared across the clearing with a long, titled vantage towards the body of the girl who had fallen near the tent, but the boots of the corporal stomped into view. The man’s dirty face, with its trailing mustaches, leaned over close into his.

Hand of war stings a good bit, don’t it, son? Sure can deal you backhand, he said.

When the brother lost consciousness his left side was numb, but a numbness that promised great pain, given time. The last thing he saw were the corporal’s hands lowering onto his collar.

He woke in the gloom of the medic’s tent with the man in the apron standing above him. The man was looking at him with profound concentration, as if he could not make him out. The tent’s inside had an aqueous look, and a warm, metallic smell abided. Every so often the relative calm was distressed by the cries of other wounded, but no one demanded the surgeon’s attention so much as the brother himself. The sounds of the skirmish were strangely muffled, as if it were happening miles away. The brother felt pain burrow down along his arm and into the gaps between his ribs, as if a living creature were eating its way from the top of his shoulder inward.

He lurched up suddenly on his palette, gripping aproned man’s wrist.

I was aiming for you. But I missed, he said.

You never were much of a shot, said the man.

Where is she laid up? said the brother. Take me to where she is. I can walk.

The man in the apron shook his head. You think you can walk, but you can’t, he said.

But she’s all right. She’s got to be. Just tell me she’s all right, he said.

When the aproned man said nothing and continued to stare, the brother did a shallow laugh.

Take me to where she is, he repeated.

It’s not something you want to see.

If you’re sparing me, then don’t, said the brother. I don’t need to be protected.

You’re about to lose your arm. You’re in no condition to go anywhere.

The brother let his eyes drift down to where the cob of his arm lay stretched alongside him. Portions of bone were showing through, glaringly white, with a finely wrought grain. There was a big swath of cotton soaking blood on his ribs and bandages wrapped around and around him to keep the pressure constant.

She’s dead, isn’t she?

She is, said the man. She was standing right behind me when you fired. You heart-shot her.

I didn’t see her.

I reckoned as much.

The brother sat up. Someone’s got to tell her people.

You’d be the logical choice for that. As soon as you’re fixed, you can go on and tell them. But first things first, he said. That arm. It’s got to go soon if you want to keep breathing.

When this arm is gone, I will still have the other. And men have done worse, with just one arm. Besides, said the brother, eyes softening some. To let me off easy is the worst you can do.

If it gladdens your twisted sense of right, I reckon I’ll go it without anesthetic.

You do that, the brother said. And wake me up if I pass out.

Though he appeared on the verge of responding to this, the man in the apron shook his head. He set the freezing saw-teeth in a deep groove of muscle just below the brother’s shoulder. When the brother looked up he was gritting his teeth and tearing up a little in the corners of his eyes. But the man regained composure with a powerful stroke that freckled his face and smock with blood.

How long he slept he could not say, for he woke in unspecified dawn, alone. The man in the bloody smock was gone, and the only other presences that he could detect were those of the men laid up to either side of him. He rose on the cot and scanned the room for something to help him take his bearings, but all he saw were supine figures half-submerged in pale blue light. His posture felt off and he looked himself over. A mummified stump where his left arm had been. He willed the stump twitch, and it did. He lay back. Then sat up again. He was sweating profusely. A dull, diffuse pain, or the specter of pain, was running up and down his side. He lowered his feet to the floor with a grimace, settled himself against a stake, and strategically leaned left—right, right—left, to get a sense for his new equilibrium. He emerged from the tent on a crutch at his right, a Union issue blanket cowled about him in the heat. Woodsmoke and gunsmoke and spirits and blood encumbered the air now the battle was through. The field was hot, festooned with bugs, and windless as a bayou.

Medics of both allegiances trolled through the slaughter on foot or by deadcart, scaring up weapons for redistribution. They collected stray rations, compasses, telescopes, spurs, saddle-winches, shot-pouches, horseshoes, odds and ends of uniforms as small as gold braids, brass buttons, and tassel, or as integral as riding boots, cavalry jackets and three-cornered hats. The solider’s kit they tossed en mass into huge sacks hanging over their shoulders; with the uneaten rations they did the same, unless they could be made a meal of; and with the effects of the deceased they let their consciences contend, for there was many a man among their party who knelt to bite an unclaimed ring, or to slip a fob-watch from a cavalry jacket and twine it around his wrist, with four others. Weaving among their legs went hogs, and scurvied dogs, and plume-tailed foxes, flirting with the meals that they would make of the unburied before the day was out.

The brother watched these scavengers, cold despite the heat. One-armed and lucky to be, all considered. And he expected to see among these men, resplendent in their robes of doom, the hag and the child and the faceless man come to claim his soul. But they were nowhere. He looked for them and looked for them, scanning the field twice over, then thrice. First among the medics, then the dead, then the field officers smoking their pipes beneath canvas tents pitched along the perimeter, then the haggard infantry fanning themselves, crouched in their blood-stiffened clothes, drinking coffee, while a chaplain in his wide, blue sash gathered some men around for prayer. And here was his brother, crouched over a bucket, washing the blood from his hands in the dawn. They were the hands of a surgeon, strong and dexterous, twice the size of Grady’s own. He was watching the battlefield in profile, not aware of Grady yet, and he seemed to see nothing but what was in front of him: the humdrum blasphemy of war. But what else did he see in that broad killing field? What manner of angel? What manner of man? What did he see that his brother could not, who now crutched back inside the tent? His brother, who lay on his cot in the heat, and tried to conceive of what he’d done.

* * *Adrian Van Young teaches writing and literature at the Buckingham, Browne and Nichols School, Boston College, and Grub Street, in Boston. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in Lumina, Gigantic, and The Believer. He is currently writing a historical novel based on the life of William H. Mumler, the father of spirit photography, and his clairvoyant wife, Hannah Mumler.

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?Having your characters speak not only out of the past, but out of the present as well.