A Sword for the King

Translated by G. K. Werner

Translator’s Note: Like Robin Hood, Arthur Pendragon’s legend grew in the telling, from the 6th century tales of Taliesin and other Welsh bards (later collected in the 14th century Mabinogion), to an explosion of medieval romances culminating in Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (c.1470). And of course, as with Robin Hood, modern movies and novels abound.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (c.1139) popularized King Arthur’s exploits for the Clerk’s generation. The Normans loved it. But for them, Geoffrey’s ‘history’ was a two-edged sword. It portrayed Arthur as their ancestor, bequeathing Normans a heroic past comparable to the legends of Charlemagne. But, by not recording Arthur’s death, Geoffrey may have inadvertently fostered their foe’s eternal hope: the Welsh hope that Arthur, Wales’ greatest warrior, would return at the time of Wales’ greatest need. And what greater need could there be than freeing Wales from the Norman yoke?

From the Clerk of Copmanhurst’s first letter: Robert Hood rode and hunted and dined with Henry, accompanying the king in all his endeavors (save womanizing)—and Robert a Saxon! Such a thing had been unheard of in past reigns, but Henry was marvelously open-minded. And Robert was a man of learning; this above all the king admired in him. Henry devoured books as voraciously as he did women and kingdoms. He gathered to his side the scholars and wise men of the day, men like Foliot of London, Walter Map, and John of Oxford—men like Gerald of Wales and Thomas a Becket, he who had once been Henry’s best friend, a man Robert greatly admired.

The Tale:

Glastonbury Tor(1), October, 1163

The small party approached the hill on foot from the southwest, following a barely discernable twilit path through treacherous bogs and low-lying mist. Gerald of Wales(2) guided them, followed by Robert Hood, the king’s builder; Brother Michael Tuck of Fountains Abbey; Thomas a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury; and several monks from nearby Glastonbury Abbey.

Robert’s eyes were on the hill rising above Gerald’s head, eyes wide with hope and excitement despite his better judgment. Could this towering hill, this tor, as the locals called it, indeed be Avalon, the legendary isle to which mysterious damsels had ferried Arthur to heal his mortal wound? More to the point, could it be the place in which even now Excalibur(3) rested?

It certainly looked like an island in the twilight, rising out of misty marshland. The only dry approach was Pomparles which they had crossed—the Bridge Perilous spanning River Brue at the point where, according to legend, Bedwyr returned Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake after the Battle of Camlann. Robert had always loved tales of Arthur Pendragon. The name, Avalon, had something to do with apples, he recalled; and sure enough, apple trees grew here in abundance. Ynys Witrin, the ancients had named this hill—“The Island of Glass,” Robert translated aloud.

“And the remains of Caer Wydyr?” Michael suggested, pointing to the man-made terrace, an ancient structure as old as Stonehenge, winding its way around the tor’s base. “FORT of Glass!” Michael boomed suddenly in the misty stillness as though he could shatter it.

“Caer Wydyr also happens to be one of the names for the Celtic Otherworld,” said their guide, Gerald of Wales. “Some ancient sources maintain that Glastonbury Tor is hollow and its summit conceals the entrance to Faerie.”

“The place to which druids sent dying kings.” Michael made his voice quake with awe. “Perhaps we’ll discover their ghosts.” He winked at Robert who had missed his old friend, seldom together in recent years. But Michael’s habitual playfulness seemed irreverent in this place.

“It is my hope,” said Gerald, ignoring Michael’s mocking tone, “that we will discover merely Arthur Pendragon’s tomb, and unearth his sword for Henry. Though I did choose this night, the eve of All Saints(4), as our best chance of entering Faerie, should we have to, and if in fact is this place touches it.”

“A magical place,” muttered one of the monks who had accompanied them from Glastonbury Abbey.

“Ho ho!” burst from Michael’s huge belly. “Magic, you say? What sort of magic might that be?” Michael performed magic these days—so Robert had heard. In addition to plying his gift for languages and marvelous swordplay, Michael had become Fountain Abbey’s first physician and surgeon. To the folk knowledge acquired from his mother he had added the medical experience of Hippocrates and Dioscorides. After translating Pliny’s Historia Naturali he had planted Fountain’s first medicinal garden(5). Plants and minerals surrendered their secrets to him one by one.

“Folk have had visions up there,” said the Glastonbury monk.

“Hah! Visions!” said Michael. “What sort of visions, brother? Visions conjured by unseen agencies? Or visions carried up with them?”

“Carried with them? How so?”

“In a flask, brother! In a skin!”

The monk pondered this as the path turned up the hill, and then suddenly looked indignant. “I should hope not, Brother Michael. We discourage lingering over the wine-cup.”

“Now there’s an evil practice!” said Michael, not specifying which he meant—the lingering or the discouraging. “Who has had these visions then?”

“Why, our own Saint Collen(6), for one.”

“Did he have a vision of Arthur’s ghost?”

“Nay. Visions of the Fair Folk and—“

A sign from the Archbishop silenced the monk. At forty-six, Thomas a Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, was a man in his prime: tall, vigorous, dark-haired and handsome despite a pale complexion and prominent nose. He spoke with gentle authority. “This place was sanctified, long since. Let us not speak of those defeated at the cross.” Demons, the Archbishop meant, disguised as ghosts and faeries. Robert had discussed the topic with him more than once—theoretical discussions disturbingly relevant here and now on their way to opening a hoary king’s grave at twilight of an All Saints eve for the purpose of stealing his sword.

They climbed out of the heavy mist that soaked hair and tunic, and the buildings on the tor’s summit came clearly into view against a dark blue velvety sky.

“Your Grace,” said Michael, “do you believe the little church up there was truly founded by Joseph of Arimathea?”(7)

“Holy Writ does not reveal the answer to that, Brother Michael,” Thomas replied. Like Michael, he had read the Bible cover-board to cover-board and possessed a remarkably keen memory. “And there is no reliable evidence to suggest that Joseph ever set foot in England.”

“But what of the Thorn?” asked Michael, and everyone glanced back at Wearyall Hill, another ‘isle’ rising above marsh and mist. At its summit a lonely wisp of a tree, permanently bent by the wind, leaned against the full moon. “Thorn trees are not indigenous to our land. Could that indeed have sprouted from Joseph’s thorn-staff as these scholarly monks maintain?” Robert knew his friend loved a good folk tale or legend, but gave little credence to either.

Thomas glanced at Robert as if to say, You invited him along, can you not contain him? “Who is to say?” said Thomas aloud. “This ground has been called by some ‘the holiest earth in all the land’. Only here has there been an unbroken line of Christian worship in England from the first missionaries till now.”

This comforted Robert, somewhat. Not that he was any more superstitious than Michael. Father Wilibald had taught him better than that, and Christ in him would keep him safe from demons, or whatever ghosts and faeries might be.

Their path now became quite vertical as they climbed rough-cut stone steps leading to Glastonbury Tor’s summit. To dispel the gloom, Michael broke into a song about midnight rambles and chance meetings, a dalliance and a duel.

The Archbishop fell into step with Robert. “Did he learn that ballad at Fountains?”

Robert shook his head. Michael enjoyed scandalizing fellow monks with tavern songs he picked up on his ‘pilgrimages’. “Not at Fountains Abbey, your grace.”

“I am relieved to hear it, Robert. It would be dull business to follow a sword quest with an abbey inspection.” He leaned close to Robert’s ear to speak beneath Michael’s ribald song. “You know why Henry chose you for this ‘quest,’ do you not?”

The question startled Robert. But the answer was obvious. “Because, I am his builder. I know stone work and the cairn up there must be opened with respect and safety. And if there is a passage leading…elsewhere…I may judge its safety as well.”

“Is that the only reason? Think about it.”

What was the archbishop after? Why the conspiratorial tone? “Henry trusts me,” said Robert, remembering the king’s words: You alone I trust to fetch my sword—you, my Bedwyr.

Thomas raised a ringed finger. “Why does he want the sword?”

The blasted Welsh still stand in my way, Henry had raged at Thomas a Becket not many days ago. Why should I not claim Arthur as my beloved forefather and, with his sword, unite all of England under my rule? Norman, Saxon, Welshman, and Scott? Can you imagine? Then he’d gone a step too far for the pious archbishop, Robert there to witness. The secular and the divine united in the God-given sword of my ancestors!

Folly! Thomas had countered. If the sword ever existed and is, in fact, now revealed to us—it is a sword, not of God, but of the Devil.

Fashioned in the world of Faerie, Becket.

Destined for Hell, Henry.

Destined for my hand. A legend unearthed in our day—a miracle, surely.

The Archbishop’s mastery of extemporary speech and debate was only ever foiled by Henry. The Father of Lies performs miracles as well, Henry. False miracles!

Bah! And so we should let it lie for any Tom, Dick or Harry(8) to dig up? I tell you, I shall have Excalibur.

“The king wants to keep it from falling into the wrong hands,” said Robert.

“Then why did he not come for it himself?” asked Thomas.

And why did you? Robert wondered. He and Michael and their guide, Gerald of Wales, had been surprised to find Canterbury’s Archbishop waiting for them at an inn along the way, cloaked against the chill October weather, deep-hooded and, most surprising of all, unattended. Robert was pleased to have Thomas’ company, but strongly doubted Henry knew of it. Or that Henry would be pleased!

“Nearly there,” Gerald called down to them. The tall young man paused on the hillside for everyone to almost catch up, before springing onward and upward, skipping steps like a mountain cat, his enthusiasm drawing them up and up and up toward the cairn.

Robert had witnessed how Gerald’s energy and self-assurance had immediately endeared him to Henry. That, and his scholarship—particularly his research into a certain prophecy attributed to Merlin, recorded on an ancient parchment and buried in Glastonbury’s extensive archives—a prophecy that had apparently sent him galloping off to the king in London—and back again to Glastonbury to guide them up the tor to the ancient cairn he hinted was the entrance to Faerie, the very place to which the Lady of the Lake had taken Arthur and his sword.

“Ask yourself this, as well,” said Thomas at Robert’s ear. “How it is that a novice finds a parchment-prophecy missed by archivists and scholars for more than six centuries?”

Atop the tor, Gerald ushered them across open turf. They passed a large stone cross, (Saxon-built, Robert noted); the Old Church, fallen into disrepair, a wattle and daub(9) structure far older than the cross; several wooden buildings with extinguished hearths; an abandoned furnace and rotting bellows; a latrine of later design—and arrived at the cairn, a mound of stones as large as a small, upside-down ship of Danish design.

“Here it is,” Gerald declared, his strikingly handsome face glowing with excitement.

“By it, do you mean what I think you mean?” asked Michael.

“According to my sources, this is Arthur’s tomb, possibly the entrance to Faerie.”

“An ale-barrel’s a more likely entrance to Faerie Land than a barrow.”

Ignoring Michael, Gerald addressed the party: “Within this mound—”

“Where is the entrance to Faerie’s entrance?” asked Michael.

Gerald indicated a stone that only a giant could have placed. “Beyond this door-stone—“

“How do you propose we move it, brother?” Michael asked.

“The monks of Glastonbury Abbey have graciously supplied us with tools.” Another flourish of Gerald’s hand drew their attention to pikes and shovels lying nearby in the short grass. “And a man of your prodigious strength, coupled with my own—”

Michael groaned loudly. “The stone’s thrice my size!”

But proved easier to move than any would have guessed. It popped off and rolled down the hill, missing toes by inches.

They stood before the open grave, a hole in the hillside that led to hell for all any of them knew or guessed, a gaping maw out of which might crawl all manner of fell creature. Everyone crossed themselves, some muttered prayers, leaning on shovels and pikes or hunching with hands on knees to peer into its depth (at a safe distance), their breath ghosting in the cool night air.

“The land of the dead,” someone said.

“Not by its aroma,” Michael noted. “Earthy and old in there. A bit mildewy perhaps, but hardly the stench of death.”

“The cairn is ancient,” said Thomas. “Its occupant long since decayed.”

“Unless,” said Gerald, eyes sparkling in the torchlight, “it was not built as a tomb.”

Thomas shook his head. There was no love lost between these two churchmen, not since Thomas learned of Gerald’s heart’s desire—the Bishopric of Saint David’s(10) independent of Canterbury’s authority—the very thing Henry would contrive for Gerald if he successfully delivered Excalibur. “It is simply the grave of a forgotten warrior,” said Thomas.

“And yet,” said Gerald, “according to my sources, raised upon the very spot in which Faerie touches our world. In fact, ‘tis said, on this night each year, at midnight—”

“And you believe this drivel?” said Thomas. “You, who aspire to become a Christian bishop?”

Gerald scowled at him. “Drivel? Does Your Grace so readily dismiss supernatural agencies? According to my sources—”

“A mythical wizard’s prophecy? Retold by a legendary bard, and recorded by an unknown cleric?”

“A divinely inspired unknown cleric.”

Thomas snorted derisively.

“Why not, Your Grace? Have you ever considered that the Fair Folk might be an angelic order, and not mere superstition?”

“Yes I have. But whose angels would they be?”

“Shall we enter and see for ourselves?” asked Gerald, bowing.

Thomas lifted his eyebrows. “You first.”

* * *

Gerald had no intention of allowing anyone else to be first, though Robert who had strung his bow, and Michael who “Miracle of miracles!” had discovered a sword in his suspiciously rigid bedroll, both volunteered. That left Thomas a protected fourth in line, and the Glastonbury delegation to bring up the rear.

A narrow corridor led through the cairn’s interior. By torchlight they made their way down its length. Inspecting the walls as they went, Robert assured them the structure was sound despite great age. From outside, the stones appeared to have been haphazardly placed, but the corridor within had been built with close-fitting, well-placed stones, framed by heavy rectangular supports at regular intervals, and capped by flat, rough-cut slabs. The corridor ran north fourteen paces and ended in a small hive shaped chamber.

“Watch your step here,” said Gerald as he entered the chamber.

The others filed in to discover, several steps away, a pit yawning before them, a circle within a circle at the center of the dirt floor.

“What do you suppose this could be?” asked Michael.

“A well?” one of the monks suggested.

“In a tomb?”

“It could be a fire-pit,” said Thomas. “Some ancient tribes burned their dead as heathen Vikings do.”

“No scarring from fire,” said Robert on one knee, examining the stone rim. “And no bottom in sight,” he added, holding his torch over the opening. “Crematoriums would not be so deep.”

“Where does it end?” whispered a monk.

“In Faerie, no doubt,” said Michael, and his laughter echoed loudly in the chamber, causing the Glastonbury monks to cross themselves again. Robert found a small stone and tossed it in. They waited six heartbeats for it to strike bottom. No splash—a dry well, if well it was. “The land of Nudd(11) has solid ground at least,” said Michael.

Thomas clucked his tongue disapprovingly.

“Ho!” Michael boomed. “That is why we have come, is it not? To find Faerie? To seek the lost Excalibur?”

“Or prove the fallacy,” said Thomas.

He and Michael stared at each other.

“Agreed,” said Michael.

Thomas smiled.

Gerald looked askance at them, put out by their exchange.

“I find no evidence of a concealed closet or nook,” said Robert who, torch in hand, had been working his way around the chamber’s wall, running his fingers over the stonework, here and there applying a pry-bar from his tinker’s kit.

“Our quest lies beneath our feet,” said Gerald. “According to my sources—”

“No steps,” said Michael.

“I have the next best thing,” said Gerald, producing a coil of rope from his pack.

“What foresight!” said Michael. “Though I’d hardly call it the next best thing.”

Robert dropped his torch into the shaft. The stones appeared to be rough-cut but with no outcroppings or jagged points to tear skin or crack pates(12). Neither did he spot handholds in the torch’s swift plunge. “The floor looks flat down there,” he said. “I think the shaft ends some feet above it, which indicates an open area, a gallery or man-made chamber.”

“Safe, do you think?” asked a monk.

“Relatively,” said Robert.

“But what might greet us down below?” asked another.

Robert looked at Michael. Michael shrugged.

“The Fair Folk of the Undying Realm,” said Gerald, tying his rope to a jutting stone.

“Do you believe in goblins as well?” asked Thomas.

Robert and Michael studied the pit. “Close quarters for a bow,” said Michael. “Close quarters for a sword,” said Robert.

“No need for either,” said Gerald, tossing the other end of his rope down the shaft. “According to the old legends, the only evil in Faerie is that which a man brings with him.”

Robert and Michael, unconvinced, slung longbow and broadsword to their back and drew their shorter sax-knives in preparation for the descent.

But, once again, Gerald took the lead, nimbly slipping over the rim and down his rope.

The Underworld

“Sheath your blades, my friends,” said Gerald as Robert and then Michael dropped down beside him. “Mustn’t insult our hosts.”

Was he serious?

The shaft ended ten feet above their heads, and a crystalline gallery opened in every direction. Its rocky formations glistened in their torchlight—a palace of columns and spears and intricately tapestried walls—a breathtaking sight. “The Isle of Glass indeed,” muttered Michael.

“Nudd’s palace?” asked Gerald. “Truth behind the legend?”

Thomas arrived with a grunt. “I’m getting too old for this sort of thing,” he said, then noticed his surroundings. “Miraculous!” he managed after a moment.

“Your blades,” said Gerald. Robert and Michael complied this time, reluctantly sheathing their sax-knives.

The three monks from the abbey descended the rope without incident, young men, chosen for strength of limb as well as honest witnessing.

“Which way?” asked Robert. There looked to be four passageways leading in four different directions.

“This one,” said Gerald, pointing to the widest.

“Why?” asked Thomas.

“North,” replied Gerald. “Faerie always lies north.”

“According to your sources?” asked Thomas.

“Common knowledge,” said Gerald.

“The wide road that leads to destruction?”(13) Michael suggested.

“Watch out for gaps and precipices,” Robert warned as they set off, Gerald, as always, in the lead.

The passageway, dazzling by torchlight, twisted this way and that till all sense of north was confounded. It descended in slopes and ankle twisting, step-like formations. At length they came to believe they had passed beneath ground level under the tor. If the passageway had branched at any point, they would have been lost, but as it was, they need only go back the way they had come to reach the cairn’s shaft.

The crystalline nature of the rock darkened into grey surfaces as they descended.

“How far must we go before giving up the ghost?” asked Michael. Though one of the party’s youngest, the night’s exertions winded him the most.

“A little further,” Gerald urged.

Around the next bend, the passageway widened suddenly into a small gallery, its walls and vaulted roof pure crystal once more. At its center, stood a block of crystal cut in the shape of an altar and impaled by something tall and slim—an empty, jewel encrusted scabbard which, by its size, must once have held a mighty broadsword.

“But where’s the sword?” someone asked as they cautiously approached it.

“And what is that?” asked Robert, pointing to a darkness at the altar’s center—a huge, man-size object.

“Who is that, you mean,” said Michael.

A red-bearded, red-maned giant of a man lay within. He wore a blue robe, trimmed in white fur, beneath which could be glimpsed silver mail. A simple gold ring encircled his lofty brow. His fist gripped the point of the bejeweled scabbard that penetrated the altar. “Is he dead?” someone asked.

“It’s like he were frozen in ice,” someone else said.

The giant’s eyes snapped open; everyone took a step back—and crossed themselves and gaped, speechless—even doubting Thomas a Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury—even the skeptical Brother Michael Tuck of Fountains Abbey.

“A corpse’s reflex,” said a monk knowingly though tremulously.

“In a centuries old corpse?” murmured another.

The giant’s eyes found Robert’s, and his hand opened.

“I’m thinking not,” said Michael. Robert stood speechless, heart racing.

The giant did not move again, but he had released the scabbard! He stared at Robert.

“Take it,” Gerald urged him. “In behalf of the king.”

Robert looked to Thomas. The Archbishop nodded.

Robert warily approached the altar, examined the scabbard, and then drew it forth from hand and rock.

A blinding flash of light burst from the altar. And, when their eyes refocused, the giant was gone. Vanished!

“Ho ho!” laughed Michael, leaping forward to examine the empty altar. “Now that is what I call magic!”

The Glastonbury monks gathered around Robert, ogling the scabbard, chattering nervously about the apparition—Arthur’s ghost?—a faerie prank?—or was it Arthur himself, alive in the flesh? Could it be? Gerald, in their midst, nodded sagely. Thomas stood apart, brows knit in deep thought.

“A fine scabbard,” said Michael, turning to examine its rubies and sapphires. “Must be worth a king’s ransom!”

“The legend is that while Arthur wore it, he could not be slain,” said Gerald.

“Henry will love that!” said Thomas.

“What next?” asked Michael. “Where is the sword?”

“And which way do we go now?” asked one of the monks excitedly. There were several dark passageways descending off the crystalline gallery.

“Listen!” said Robert. They heard a faint trickling.

“An underground stream?” asked Michael.

“Possibly,” said Robert.

“The Lady of the Lake could have brought the sword here by means of some hidden waterway,” said Gerald.

“Do you think so?” asked Michael, rolling his eyes.

Following the trickling sound of water, they proceeded on by torch light, a fairly straight course. But the passageway soon ended and an enormous, high vaulted cavern opened before them, filled with water that lapped within inches of their boots—a large hidden lake. At its far end an underground stream cascaded into its depths. Cavern, fall and lake glowed with an eerie green luminescence.

“Look!” cried a monk. His trembling finger pointed at the lake.

Everyone leaned forward, eyes bulging to penetrate the water. Something glowed whitely beneath the surface. A filmy white flowing something! And it was rising. Drawing nearer!

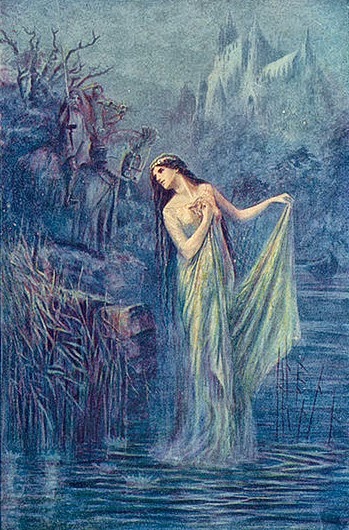

For the second time since their descent, the party, collectively, took a step back—then two or three more. Ever close to thought’s surface lay the eldritch explanations for unexpected drownings, the old tales of nixies and nightmares—and the Lady of the Lake! Was that a woman’s shape within the diaphanous white gown?

She rose to the surface, floated on her back, slender feet pointed toward them. A woman—no doubt now—tall, slender and shapely, her golden hair elaborately braided and coiled. A great, two-handed broadsword lay lengthwise on her body. Her hands enfolded the gilded hilt, pressing it to her breast. The silver blade flashed like a star.

“Is she dead too?” The monk’s question was shockingly answered.

She rose from the surface of the lake, stiff as a corpse, pivoting upright till she stood before them, tall and straight, regal as a queen—standing barefoot on the surface of the lake itself! The sword’s pommel contained a blue gemstone the size of a plum. It winked in the torchlight.

Then her eyes snapped open. And everyone gasped and crossed themselves again, everyone except Thomas and Michael. Like the red-bearded giant, her eyes found Robert’s. “From the king who was,” she said. Her voice matched the musical quality of the bubbling cascade at her back. She proffered him the sword, the guard resting on her open palms, its gold and silver resplendent upon the water. “To the king who is,” she said.

Gerald nudged Robert with an elbow.

Barely breathing, Robert stepped to the edge of the lake and held out the scabbard, not daring to accept the sword with his own hands. Solemnly, she slid the broadsword home. With a whoosh, a shimmering golden mist filled the air. At Robert’s back monks cried out in awe.

The lady smiled. She had a wide mouth and smiled like a cat. Robert felt, as the king’s emissary, he ought to say something in behalf of Henry. But she raised a hand in farewell and abruptly sank, dropping beneath the surface like a rock, her gown fanning out, winging her into the depths.

Another whoosh, and more gold dust mist filled the air. Someone coughed. Then several others as Robert examined the sheathed sword in his hands—the strong, simple design—elegant—unlike its gaudy scabbard. Save for the clear blue gem, it was a practical weapon—a warrior’s weapon. A giant warrior’s weapon! It weighed more than a stone-cutters mallet. Michael coughed nearby. Should he allow him to hold it, intended as it was for the king’s hand? Surprisingly, Michael was not interested in the sword. He stooped to pick something up—an ordinary reed, like those growing by any lake in England. He turned it over, and over again in his big, thick hand. “Hollow,” said Michael, silently mouthing the word, a quizzical look in his eyes.

Of course it was hollow! Weren’t all reeds hollow?

“Tar,” Michael whispered, pointing to the reed’s lip.

Whoosh—the golden mist thickened.

The others had gathered around him now, awed by the sword, but babbling as incoherently as Michael.

Gerald smiled smugly, and then laughed aloud.

Thomas was shaking his head.

Robert had trouble focusing his mind. The sparkling dust filled his vision. Glamour(14), he wanted to say to Michael. But, his senses swam, and he suddenly feared he was sinking, drowning in golden stars!

III

The Tor, reprised

Robert awoke on the tor, flat on his back, staring at the stars—ordinary stars in an ordinary night sky.

His bow! He sat bolt upright. There it was, lying at his right hand. The others lay about him, most on their backs. Some stirred, rolling over or scratching drowsily as though awaking at an inn. Michael snored loudly.

The cairn rose stark in the now moonless night. The stone covered the entrance again.

Had it all been a dream? No. There was the sheathed sword, lying at his left hand.

“Hah!” cried Michael, springing to his feet, his own sword on guard in a battle stance.

“Good morning,” said Robert, impressed with Michael’s sprightliness.

“Well now,” said Michael, embarrassed by his reflexes. He cleared his throat and sheathed his blade as others rose wide-eyed, gathering their senses.

Thomas sat up slowly, looked about himself, made the sign of the cross, and immediately bowed his head in prayer.

“How did we get here?” asked a monk.

“Who sealed the cairn?” asked another.

“The Fair Folk!” said a third, crossing himself.

“Or that Arthur fellow,” said Michael. “He’s big enough to carry us out and replace the stone in one go.”

Gerald yawned, sighed, and then sat up, bemusement vying with amusement on his face. “What happened?” he asked.

“We thought you might tell us,” said Michael.

“Hmm,” said Gerald, rising and dusting himself off.

“Excalibur,” breathed one of the monks gathering around the sword. “Excalibur,” the others repeated, making it almost a chant.

“The work of angels?” asked Thomas, on his feet now, adjusting his robes. “Do you think?”

“Anything is possible, Your Grace. This may be the holiest ground in all England, as you yourself have said.”

“Did I say that?” Thomas smiled, and it was like the dawn in its sudden warmth. “Well, I’ll say this, young man—most impressive!”

Gerald beamed.

Thomas turned to Robert and Michael “Was that not the most impressive ceremony you ever witnessed?” he asked them.

Robert nodded.

“I could not believe my eyes or my ears,” said Thomas, and he was known for possessing exceptional sight and hearing.

“Neither could I!” said Michael.

And they both turned to Robert, who immediately became suspicious. Things subconsciously noticed fell into line like neatly cut stone: The ease with which a stone set in place centuries ago had moved; Gerald bringing a rope to explore a cairn, insisting their weapons be put away; Michael examining the crystal altar instead of a legendary scabbard and an ordinary reed instead of the most famous sword in Christendom—a reed by an underground lake? Gerald’s warning: Watch your step here. Michael’s words—Now that is what I call magic! (He and Michael had often debated the supernatural back in their days together at Fountains. Michael defined sleight-of-hand, and illusions like sword swallowing or flame breathing as magic—fakery for entertainment purposes as distinguished from witchcraft or sorcery.) And Thomas’ question—You know why he chose you for this, do you not? Robert did now! King Henry knew how much Robert loved tales of Arthur and his knights. He felt so gullible. And resentful! “Unbelievably wondrous!” said Robert, raising the sheathed sword to salute his two friends.

Thomas nodded, still smiling. “Then we’ll leave the sword in your care Robert, and we’ll leave Michael to lead you in prayer and meditation concerning its disposition. Come Gerald.” Thomas put a brotherly arm across Gerald’s shoulder, turning him toward Glastonbury Abbey and the path down to it. “Let us hasten back to Abbot Henry(15) to herald this wonder.”

Gerald apprehensively glanced back at Robert and Michael more than once as he, Thomas and the monks descended the tor.

The moment they passed out of earshot, Michael began sermonizing his observations and deductions.

Robert had to agree, corpses and disembodied spirits had as much use for hidden passageways in crystal altars as Lake Ladies had for lungs; reeds could be strung together with tar or pitch and, with practice, breath could be drawn through their length. He had missed the opening Michael had observed beneath the altar and never dreamed of a breathing pipe.

“What would it take to mechanically raise the Lady of the Lake?” asked Michael.

Robert thought a moment. “Well, an armature, pivoting on another rotating from a crossbar. Much like a catapult or stone-hurler.”

“Something like this?” asked Michael, handing him a parchment.

“Where did you find this?”—a sketch of a machine of some sort.

“In Gerald’s satchel among his sources.”

“You pilfered it?”

“Borrowed is a more precise term.”

“When?”

“While following him through Faerie Land. I was only after a bit of marzipan(16) he’d promised me for breakfast.”

“Clever!”

“Thank you.”

“I don’t mean you, you thief. The ropes and pulleys indicated here and here, would enable someone to raise the lady’s board, right it, and later release it, all from concealment. A simple design really.”

“And the perfect setting,” said Michael. “I believe the ancient druids of this place discovered the crystal cave and lake while drilling a well.”

“The luminescence is a natural phenomenon, I suppose.”

“Phosphorous,” said Michael. “And some sort of algae.” He knew a great deal about minerals and their properties. “Who knows how many legends began in the druids’ secret passageways.”

“What about the flash of light that cloaked Arthur’s exit?”

“Greek fire(17) of some sort. Or a powder(18) from the east I once saw demonstrated in London.”

“The glamour?” asked Robert.

“A powerful sleep inducing drug, pulverized, mixed with gold dust and cast into the air somehow. Perhaps through a pipe with a bellows. The scabbard must have contained some too.”

“And the sword?”

Michael drew it from the scabbard in Robert’s hand, examined it thoroughly. “A fine sword, beautiful and well-balanced. Expertly crafted. Worthy of a king, no question!”

“Arthur’s?”

“Not old enough. A warlord in Arthur’s day would have used a sword similar to the Roman spatha(19). Two-handed broadswords of this kind only came into use much later.” Michael knew his swords too, of course. He examined the pommel, and then the scabbard. “The jewels are genuine. The scabbard is very old. But again not old enough. Perhaps handed down in Gerald’s family.”

“This is rich!” said Robert.

“Worth a king’s ransom, I should think,” said Michael.

“The plot, I mean,” said Robert. “It’s worthy of a king as well.” He plopped down on the tor and stared at the abbey roofs far below.

“Any king in particular?” asked Michael.

Robert groaned. “What do I do now?”

“Report the truth to Henry, of course. Why so despondent? We have proof of the plot, even without re-entering the tor and scavenging around. Although if pressed we could disassemble the machine and find Arthur and the Lady.” Michael snapped his fingers. “Bellows! And a specially forged sword! I seem to recall a certain sword-smith in Derbyshire—a very tall sword-smith in Derbyshire, as a matter of fact, who—“

“Henry wanted the sword. Arthur’s sword!”

“He’ll be disappointed, I warrant you, but—”

“It’s no good! I’m sworn to fulfill my quest.”

“And so you shall. We discovered Gerald’s duplicity. Hah! We’ll be heroes!”

“And if Henry does not want the truth?”

That gave Michael pause. “Is it really possible? Henry hatched the scheme himself?”

“Entirely! You don’t know Henry as I do. And Thomas suspects him too, if the questions he asked me coming up here mean anything.” Robert related them to Michael.

His Grace secretly joining us is further proof,” said Michael. “And we don’t know who else may be involved. Abbot Henry for one! He’s probably turned a blind eye hoping to attract pilgrim donations and royal patronage."(20)

“Possibly,” said Robert.

Michael plopped down next to him. “It’s unhealthy to cross a king’s will.”

“But I’ll have no part in a lie,” said Robert.

“Neither shall I,” said Michael quickly. “Even a lie of such magnificence!”

Robert folded his arms across his chest and dropped his chin on his chest to pray.

“What to do! What to do!” said Michael.

They sat and prayed on the tor as the stars winked out one by one. But, with the morning sun’s first gleaming, Michael brightened. “Ha! I have it!” He slapped his knees and sprang to his feet. “Up! Up!” he cried. “You must ride like the wind.”

“Where to?”

“I’ll tell you.” And he did. And then he told Robert his plan.

“But how do we manage such a fantastic—?”

“Leave it to me,” said Michael. “Leave it to me. I know a little magic myself, you know. Ho, ho!”

Glastonbury Abbey, that night

The Glastonbury monks spent the day preparing a feast in honor of their legendary hero whose home they shared, and the king who would now wield his sword. They gathered that evening in their refectory to celebrate. Rules of conduct and diet were relaxed for the occasion, and the brotherhood waxed downright boisterous. Abbot Henry alone sat dour faced at table while his monks sang and jested, feasted and toasted—to King Arthur and King Henry, England’s glorious past and present!

A narrow table beneath the refectory’s cross held their prize. A plain white cloth draped the table and Excalibur was surrounded by dozens of candles lit in its honor—a simple shrine between two tall windows with stars twinkling beyond them. A special mass was planned for later in the evening.

Robert and Michael had delivered the sword to the abbey at sunrise and ridden off in a hurry. They returned late to the feast. “Where have you been all day Master Robert?” a monk called across the table. “Saw ‘im riding east fast as the wild hunt,” said another.

That was too close to the mark. While Michael spent the day in Glastonburytown purchasing certain materials suitable for the night’s entertainment, Robert had spent the day hunting down their elusive quarry.

“I had an errand,” said Robert. “King’s business.”

“To the king!” pronounced Thomas at Robert’s elbow, raising his cup.

“God bless the king!” cried one and all, raising theirs. Welshman toasting a Norman king! That wasn’t something you saw every day. Or did they toast Arthur?

As conversation and jests resumed around the table, Robert tilted his cup in thanks to Thomas’ timely distraction. “I know why he chose me,” said Robert, answering the question Thomas had posed on the tor. “I’m gullible.”

Thomas spoke beneath revelry’s din: “I have never considered you gullible. Inexperience is nothing of which to be ashamed. And, he chose you for your honesty, hoping his liege men and allies, even his enemies, would trust your word as a witness, your judgment as a man of good sense and discernment.”

Robert flushed. Trust him to stupidly support a royal subterfuge!

“However,” Thomas put his hand on Robert’s forearm, “a word of caution. Follow no man blindly. You are somewhat in awe of him.”

nd of Thomas a Becket also, Robert realized in that moment. Thomas and Henry—great friends and archrivals! Between them, they could rend lesser men.

An owl hooted outside the refectory’s tall windows. It sounded reasonably like an owl anyway. It was time. Robert rose and lifted his cup to the assembly. “I would like to propose a toast as well,” he said. The assembly rose, dutifully turning to him and lifting theirs. But just then, Robert’s eyes widened, and all eyes sped to their target.

“Aiiiiiiii!” cried a monk at the far end of the table, closest to Excalibur’s shrine.

A tall, lean figure stood on the small table, black boots straddling the sword, black robes a-swirl. His long-fingered hands gesticulated wildly in the multiple-candlelight to send shadows whirling like spectres in the vaulting. His long white hair and beard bristled like porcupine quills, even his eyebrows. His nose was a stabbing knife, and his bloodshot eyes pierced all they met.

“Merlin!” gasped a monk, jumping to his feet and upsetting his chair.

“Can it be?” asked another.

“I think not!” shouted Gerald, rising.

“He’s after the sword!” cried a lay brother as everyone came to their feet.

“Somebody stop him!” somebody cried.

“Excalibur is Arthur’s!” Merlin proclaimed in a raspy voice, lifting the sword from the table. “And Arthur’s alone!”

“Nay!” cried Michael. “The Lady of the Lake has bequeathed Excalibur unto King Henry Fitz-Empress.”

“It was no longer hers to give,” Merlin nasally intoned. “I shall hold it against Arthur’s return.”

“You shall not!”

“It is preordained!”

“Preordained, my arse!” cried Michael, and the monks gasped in unison. He whisked his sword from beneath his chair. “Cold steel will determine the matter!” He leapt onto the long dinner table and gathered himself for a charge down its length. But Merlin struck first—a long slim finger pointed at Michael’s blade, flicked aside, and the sword flew from Michael’s hand to strike the stone flooring with a spark and a resounding clang.

Everyone gasped again.

Merlin held Excalibur triumphantly above his head and opened his mouth for some fell pronouncement. An arrow struck the blade and Excalibur hit the floor with a bigger spark and a louder clang than had Michael’s sword.

Robert stood in the doorway, having retrieved his bow and quiver from the corridor, a second arrow pointed at Merlin, his bowstring drawn to his ear. “Henry shall keep Excalibur against Arthur’s return,” said Robert, quietly but firmly.

“It is not his task, but mine,” snapped Merlin. He pointed at Robert’s bow and flicked his finger. The arrow jumped sidewise off the string to land harmlessly at Robert’s feet.

But Robert’s hands moved like magic, and a third arrow appeared on his string, drawn to his ear.

Merlin answered with a point-flick, and Robert’s bow jerked aside flinging his arrow into a nearby chair.

Again Robert nocked and drew. But, of course, pointing and flicking is quicker. Like the others, this arrow struck where Merlin gestured, this time splintering against a stone wall.

A fifth arrow leapt out the open window at Merlin’s side. The next skidded across the floor. Wherever the ancient wizard pointed, there flew Robert’s arrow, monks scattering for safety behind columns and buttresses.

The ninth, Robert’s last, quivered in a rafter high above Merlin’s head.

Robert drew his sword and Michael, still atop the table, drew his sax-knife, but Merlin shoved at the air with both hands as though taking his turn in a game of buffets. Robert and Michael fell off their feet like bowling pins.

Merlin laughed—a wild, mad, high-pitched laugh, and vanished with a boom in a cloud smoke. When it cleared, Excalibur was gone as well.

The monks dropped to their knees, murmuring and crossing themselves repeatedly. Thomas helped Robert and Michael to their feet. Enraged, Gerald rushed to the small table, frantically looked out first one window and then the other, lifted the table cloth. “Thieves!” he cried. “Thieves!”

Abbot Henry sat quietly at the table, smiling now, and nodding to himself.

V

Hathersage, Derbyshire, several days later

They rode down out of the Pennines, Robert and Michael, still laughing about rewriting the ending to Gerald’s play.

“I could have hugged the monk who cried Merlin,” said Michael.

“The abbot was pleased,” said Robert. “Did you see?”

“Grinning ear to ear,” said Michael.

“A wise man to see through our jape.”

“Apparently not so willing an accomplice in Gerald’s plot as we might have supposed.”

“No,” said Robert, “but I feel sorry for his flock. They seem to have been taken in completely.”

“Gerald was trapped,” said Michael, “just as we thought—couldn’t expose his players without exposing himself.” Michael laughed again, holding his belly with one hand and the reins with the other, before managing to speak. “Gerald’s eyes nearly popped out of his head!”

“An eye-opening experience for me too, this quest to Glastenbury Tor,” said Robert, thinking about Henry’s motives and likely complicity.

In Hathersage they inquired the way to the smith and soon dismounted before his shop. A tall young woman with long, flowing blond hair came to the door and saucily looked them up and down. “I suppose you’ll be wanting it back,” she said, arching an eyebrow.

“Only the scabbard and pommel stone,” said Robert. Gerald’s family heirlooms as Michael had supposed. Gerald could hardly claim them without incriminating himself, so Michael intended selling them to feed the poor. Scabbard and stone would feed a lot of poor.

“Not the sword?” she asked. Gerald had commissioned her husband to forge it—a time-consuming project to judge by such quality workmanship.

“Nay, it is yours to keep,” said Robert.

“Payment for your additional aid,” said Michael, who undoubtedly desired it himself.

“My thanks,” said the giant red-bearded sword-smith, arriving at her back, a merry gleam in his eye. The sword’s gold and silver inlay was worth a small fortune to them. “Of course,” he added, “a good jape at Norman expense is payment enough.” When Robert overtook them on the road, he and his wife had readily agreed to Michael’s playacting, caught as they were in their own for which Robert, as an officer of the crown, could have arrested them.

“Your winsome wife was superb, Master Smith!” said Michael. “—a convincing Lady of the Lake and a convincing Merlin not twenty four hours later. Magical!”

She smiled wryly and exaggerated a curtsy.

“I would give a hundred swords to have caught her performance first hand!” roared her huge husband who had been waiting beneath the refectory’s window with a length of reeds, a bag of ash from his shop, and his hand-bellows which had previously blown glamour in their faces.

“At least you caught her exit,” said Michael. “With both hands!” Or she’d have leapt through the window to her death.

The four had a good laugh at Norman expense.

“Well met!” cried Robert who had not had such fun since the last time Michael was with him.

“Well met indeed!” cried Michael. “What a merry band of jesters the four of us would make! Heh? If ever our Norman betters should disown us."(21)

“It occurs to me,” said Robert, “we don’t even know your names.”

“Kerry,” said the willowy woman.

“Eric Little,” replied her husband.

“Eric Little?” cried Michael, and he howled and ho-hoed till his belly almost shook loose and rolled down the lane.

“My mum named me,” said the giant quite seriously. “She was Danish. Wanted me to have a good Viking name.”

“It’s not the Eric part,” Michael barely managed between guffaws.

Tintagel Head, many weeks later

Gerald and Henry met over a chessboard on Tintagel Head. Chamberlains had set out a table and two chairs on the grassy height above Cornwall’s granite coast. The sea surrounded them, a turquoise vastness stretching into distant mystery, save where a narrow strip of rock connected Tintagel Head to the mainland. Gerald fully appreciated Henry’s wry choice of meeting places; however, contrary to legend, there were no buildings on this headland, beaten by wind and sea, no evidence of anything ever having been built here, let alone the fabled castle in which Arthur Pendragon was conceived.

They sat alone, Gerald and Henry, playing chess in a silence broken only by the cry of gulls reeling and plunging in the sea-spray, the crash of surf on jagged rock far below, and the snap-crack of the royal standard whipping in the wind above their heads. Henry was not smiling. Gerald extricated himself from one trap after another, wondered if losing would improve his future chances of winning the independent bishopric of Saint David’s, or at least keep him from ending his days on the rocks below. But Henry thrived on challenges and despised fawning courtiers. “If only you had taken on the quest yourself m’lord, in order to—“

“In order to be made a fool of in person?” Henry shouted into the wind. “Nay! I did well to distance myself from such incompetent playacting. You and those silly monks, and that confounded smith and his wife!”

You approved it, Gerald could have said, but thought better of it. “The Hathersage couple’s complicity will keep them silent,” he said instead while attacking Henry’s bishop with his rook. “The abbot and his monks have sworn never to repeat the tale, for their own reputations sake as well as their sovereign’s.”

“And I don’t want to read of it in some clerk’s ‘history’ either,” said Henry.

Gerald assured him posterity would be none the wiser.

Henry grunted skeptically, and captured his rook.

But Gerald knew should the story spread, Henry’s favorite Master Builder had loyally provided his king with a most logical explanation for the Glastonbury gambit and its outcome. Gerald had read Robert’s letter—a daring masterpiece. My thanks beyond words, for the spectacular magic prepared for us in Glastonbury, Robert had written his liege lord and king (sounding more like a certain renegade monk of Fountains Abbey, if anyone asked Gerald—which they had not.) I feel as though I truly was on a quest for Arthur’s sword. Your engineers and actors faithfully revived my favorite hero for a splendidly original play. What trouble and expense to take in behalf of your humble servant! The fact that you remembered my interest in matters Arthurian would have been gift enough.

“I don’t suppose the bishopric of Saint David’s is entirely out of the question,” Gerald chanced despite the king’s demeanor.

Henry glared at him.

“After all, it was a daring gambit. A good faith effort.”

Henry burst out laughing. “Gerald—I like you!”

“So you will arrange—”

“Just as soon as Hell freezes.”

Gerald sank in his chair. His chin dropped to his chest.

“Unless,” Henry added reflectively, a few moves later.

Gerald sat up. “My liege?”

“Well, if we can’t have Arthur’s sword, let us have him confirmed dead and in the ground.”

“A thing entirely possible,” said Gerald enthusiastically. “Arthur has certainly outlived his usefulness.”

“May he rest in peace!” said Henry, smiling again.(22)

1. tor: the peak of a bare or rocky mountain or hill (Celtic—rocky height; Welsh—heap, pile)

2. Gerald of Wales: Giraldus Cambrensis; scholar, courtier, churchman, outlaw, naturalist, traveler and diplomat; respected historian and author of seventeen books; great-grandson of Rhys ap Tewdwr, the Prince of South Wales on his mother’s side, and the son of William de Barrie, a Norman knight; born in 1145, he would be nineteen here, making the Clerk’s history the earliest record of Gerald’s activities.

3. Excalibur: Frenchified version of Caliburn, the name given Arthur’s sword in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain. The Clerk uses the name Caladfwlch throughout his letter, Arthur’s sword’s name in the earliest stories, derived from the Welsh Calad-Bolg, “Hard Lightning”.

4. All Hallows Eve: In 835, in an effort to wipe out pagan holidays, Pope Gregory IV changed the Church’s May 13th celebration for martyred saints to the Celtic November 1st festival of Samhain during which it was believed the dead returned to mingle with the living and goblins and faeries roamed the night.

5. Elsewhere in his letters, the Clerk describes the thrill he experienced as a scribe translating Hippocrates’ Greek and the De Materia Medica, (50-70 AD) of Dioscorides, a Greek army doctor who built upon Hippocrates’ work. Together with Pliny the Elder’s, these writings would eventually form the basic curriculum studied by late medieval medical scholars.

6. Saint Collin: a 7th century hermit who, according to legend, visited a Fairy Palace beneath Glastonbury Tor, sat through a fairy banquet refusing to eat anything, and escaped by flinging holy water all around, whereupon the palace disappeared.

7. Joseph of Arimathea: a wealthy Israelite and member of the Sanhedrin; he became a disciple of Jesus of Nazareth to whom he loaned his tomb for three days.

8. Since our Clerk loves puns, is he referring to Thomas a Becket, Richard (Henry’s son), and Henry himself here? Did Henry II actually say this? Previously traceable to the 16th century, this is now the earliest recorded occurrence of the saying.

9. wattle and daub: walls formed of twigs and branches surfaced with clay

10. Bishopric of Saint David’s: a post formerly held by Gerald’s uncle, David FitzGerald

11. Nudd: Gwynn ap Nudd, the main Otherworld Celtic god, whose palace was believed to be beneath Glastonbury Tor

12. pate: head

13. Jesus speaking of himself in Matthew 7:13-14: “Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.”

14. Glamour (glaymor, glamarye, or glamalye): possibly akin to fairy dust; the power by which elves reputedly transform or transport themselves, create illusion, or allow humans to see them or their world.

15. Henry of Blois, Abbot of Glastonbury 1126-1171

16. Marzipan (march pane, march bread): a confection of sugar and almond meal, probably originating in Arabia, where an almond paste is mentioned in The Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night.

17. Greek fire: an inextinguishable “liquid fire” weapon that burned even on water, said to have been invented by Callinicus, a Syrian engineer (673 AD). Eastern Roman Emperors kept its formula secret for centuries and even today, its exact chemical composition remains a mystery.

18. The earliest reference to gunpowder?

19. spatha: an ancient Roman cavalry sword, 25-38 inches long, a highly versatile weapon used for thrusting as well as slashing.

20. In his writings, Henry of Blois describes the deplorable condition in which he found the abbey upon his appointment as abbot. The community was nearly ruined, buildings crumbling, monks struggling at subsistence level.

21. Prophetic words, as witness the Clerk’s third letter.

22. Eric Little’s last days are chronicled in the Clerk’s tale, “The Log-Bridge Quarterstaff Fight”.

Gerald of Wales never did receive his heart’s desire—the Archbishopric of St. David’s on a par with Canterbury. In 1190, he returned to Glastonbury to witness the opening of a grave, purportedly Arthur’s. Gerald wrote two accounts of the exhumation: one in “Liber de Principis Instructione” (c.1193), and the other in “Speculum Ecclesiae” (c.1216).( Both can be found at www.camelot.celtic-twilight.com/infopedia/gerald_wales.htm.) Two remains were found: the skeleton of a huge man, and a smaller skeleton with “a tress of woman’s hair, blond and plaited and coiled with consummate skill.” The Clerk’s revelation of Gerald’s earlier Excalibur ‘find’ does not conclusively support modern scholars who have accused the Glastonbury monks of a publicity stunt in regard to finding Arthur’s body, but it certainly provides a motive for Gerald. Could he have engineered such a ‘find’ at the expense of two people who had crossed him? Not likely. Based upon reliable sources, Gerald could be accused of repeated opportunism, but not murder. That the bodies were those of Eric and Kerry Little is pure speculation. In any event, his second foray into Arthurian drama met with greater success than his first. Unfortunately for Giraldus Cambrensis, Henry II had died in 1189 and his son Richard cared little for Gerald’s ambition, Glastonbury’s claims, or his father’s promises.

Image of Glastonbury Tor by Michael Ely.

G. K. Werner teaches in adult prison education and the martial arts when not writing genre fiction from a Biblical perspective. In addition to Lacuna, his stories have appeared in Tower of Ivory, The Sword Review and Fear and Trembling. He lives in ‘slower lower’ Delaware with his wife (author, poet, songwriter and homemaker Virginia Ann Werner), their cats and collie (who have many tales, but never tell). Visit their blog, Narrow Way Storytellers.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

Hal Foster's Prince Valiant, 'In the days of King Arthur', is a close second to my number one favorite fictional hero, you know who. Like Robin Hood's father, my father's favorite stories involved King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. In childhood, I read the edition he read in his childhood by Henry Frith, which included such memorable lines as "clave thy pate in twain", and great illustrations by Rowland Wheelwright (depicting knights in anachronistic 15th century plate armor). From my teen years on, I read and collected the fine-art newspaper comics masterpiece, Hal Foster's Prince Valiant (a little more historically accurate). Imagine my delight when I read Geoffrey Ashe's The Quest for Arthur's Britain in my early twenties and discovered that, unlike Robin Hood, substantial evidence points to a historical Arthur Pendragon (though not so named). Later, I came across Gerald of Wale's accounts cited above, and the tie-in with Robin Hood emerged from Avalon's mists—well, from my Arthur-saturated mind.

0 comments:

Post a Comment