Centurion's Choice

by R. S. PyneCenturion Marcus Flavius Quintus of the Second Augustan Legion cursed the British weather as he did every morning and felt every one of his fifteen years with the Eagles. Roused out of a vivid nightmare by the daybreak buccina, he drifted through the staff officer’s meeting like someone still asleep and heard barely a word.

Back in his quarters now, he broke his fast with oil and bread warm from the ovens and wished there was some

garum to go with it. Stocks of fish sauce had dwindled so low that only the camp Prefect and Chief Centurion Commander could still use it. At least another five days before a resupply column arrived. Curse the Quartermaster’s crooked soul down to the Underworld and back again; the fat slug sold more supplies than he issued using his position to grow rich at the Legion’s expense. He could picture the man; an enormous belly stretched tight against a perpetually grease stained tunic. Spindly legs barely supported his weight, could not walk a hundred steps without resting; he let his assistants do all the work and then blamed them whenever things went wrong.

“Damn rain,” he said and drained his cup. He spat it out just as quickly. The wine was a second rate Falernian, the sort of thing usually given to natives. They refused to dilute it with warm water like civilized people and did not need to check for wildlife. Perhaps that was the best way. Soldiers far from home thrived on news, gossip or scandal and camp opinion still held the newt in a tribune’s goblet had been no accident.

A grim faced shadow stopped him from brooding.

“Pass it over.” Caius Lucius wrung water out of his cloak and muttered a greeting. “I need a drink and I hate to see it wasted.” The two were old friends who had served together for long enough to relax usual protocols when nobody important would object.

As duty centurion, Quintus had drawn the short straw for the third day in a row, taking out a patrol of the legion’s dregs on punishment detail. “Make your report,” he said, pulling on his helmet and made sure he looked presentable when all he wanted to do was go to the bath house and soak the chill of Britannia out of his bones.

It had leached deep into the marrow, the warmth of Ostia long forgotten. Those had been lazy sun baked days of wine and honey, two weeks of leave at his brother-in-law’s villa. The children, he would happily drown in the sea; they were a nuisance, even if they shared his blood. The oldest boy, Lucius, demanded tales of blood and battle and then had nightmares about it afterwards. The girl, Livia, was pretty as her mother and would break as many hearts; she had mastered sincere apologies to the Household Gods with fingers behind her back. In Ostia, the skies were blue and cloudless.

It was raining outside. It always seemed to be raining. The weak sun had not shown his face in days, chased away by lowering storm clouds and a damp, gray mist that hovered like an inconvenient uncle at a wedding feast.

Quintus thought once more of Ostian sunshine, the smell of the sea and of sun baked streets and wine shops, fresh cooked seafood, meats and exotic spices. The great and the good of Rome paraded the paved main streets in their best clothes, but Ostia came alive at night when abandoned to the lesser ranks.

His optio pulled him back out of the daydream.

“The men are all formed up and waiting. Two more have deserted without trace and another lost an argument with a loaded bullock wagon so will not be joining us again in this world. Aulus the Rat is swinging the plumb-line again. He said he was too sick to march anywhere when all he had was a slight sniffle. I kicked his arse back into line and threatened to put him on three months latrine duty. I might just do it anyway.”

“Good. Walk with me,”

The two men fell into step, easy in each other’s company, walking as equals until it was necessary to do otherwise. A sorry looking column waited for them, the sky above them heavy with the promise of a thunderstorm. He smelt oily wet wool and stale

posca – the mixture of water and sour wine that made up a soldier’s daily ration mixed with the sweet native brew that took some getting used to. An acquired taste but soldiers never wasted a chance to get drunk.

“Stand up straight,” Caius Lucius savaged one of the men for lounging on his shield while the others snapped to attention and tried to look keen. They did not make much of an effort.

Several of them had rust spots between plates of their lorica segmentata, the scale armour that should have been mirror bright.

“Next time, more polishing and less drink,” Lucius snarled, using his vine stick to point out a large rust stain. The optio had spent years waiting for a vacancy among the centurionate; competent and loyal as any hunting dog. He deserved his promotion and, by the Gods, was sure to get it sooner or later – stepping into dead men’s hobnails as easily as a high born lady put on a new

stola.

He glared down at the malingering filth that called itself a Roman citizen and dragged the section down to ever lower standards.“What do you want now, maggot?”

It raised a hand and refused to be silent. “I need to see the medic.” Aulus had a face like a slapped fish head kept more than three months in the fermentation vat. The Gods in their wisdom ensured that he found his way into the legions; a rich relative ensuring he passed the medical even when he was unfit to serve. A liar, bone idle and unreliable, the best thing that could happen to him would be a Celtic spear in the gut but he was indestructible. Where much better men fell in battle, he survived without a scratch, when most soldiers obeyed orders, he avoided them.

“I am ill, Sir.”

“Shut your mouth.” Caius Lucius roared his impatience, but it was not enough to stop the protests.

“Think I have foot rot, Sir, and everything aches. My head hurts. I was sick this morning.”

“That is how the rest of us feel about you.” A vine cane bounced off the man’s helmet, sound echoing across the valley. “Another word and you will empty Latrine Number Three with a number three ear scoop.”

The threat worked and nobody else tried to claim they were ill.

They shouldered their packs, loaded down by digging tools, cookware and everything else thought necessary for campaign life, almost looked like soldiers as they marched through the gates at fast pace. Scouts reported nothing that morning, no hostiles or events worthy of attention. Just another routine patrol; the dregs brought together to spare better men from boredom. They slowed to campaign step, the mile eating stride developed by the legions and learned by even the dullest recruit.

Both Centurion and Optio had worked their way up from the ranks and spent enough time as Marius’ Mules to know the weight. They had marched in full armor under stronger suns than Britannia and did not miss the extra ninety pounds of kit and a need to build the camp before they could sleep in it or fight a battle afterwards. Half way through the circuit, the men had lost what little enthusiasm they started with. They muttered curses, any excuse to slow down. Centurion Marcus Flavius Quintus had heard it all before; he strode away and forced them to run to keep up with him. He listened to the swear words dying away to be replaced by heavy breathing, savored the sound for a heartbeat until his optio gave him something else to think about.

“Guess who is missing?” His weather beaten face split in a humorless grin.

Quintus could guess. Damn him.

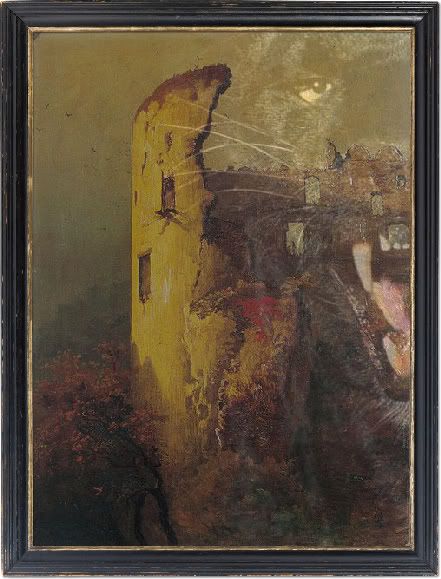

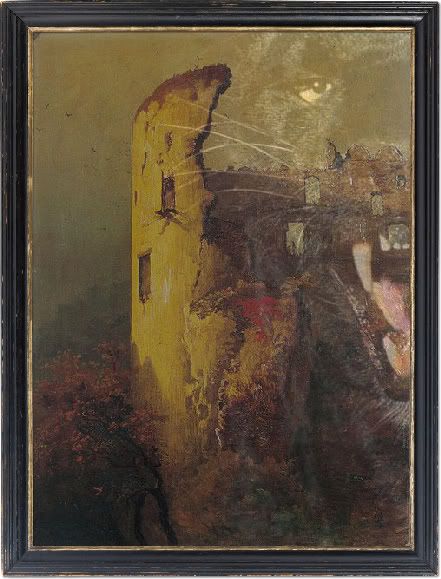

He looked around into the dark forest that bordered a newly made road as if waiting to strike and felt eyes staring back at him. Worse things than wolves lurked among the ancient gnarled oaks, rumors of druidic sacrifice and dark rites still strong in the forest depths. He decided not to send men to look in case they got the same idea and wandered away. Aulus always turned up again like a bent copper piece on an offering plate.

Their lost sheep fell back into step with the patrol as if he had never been away from it, had the gall to look surprised when questions were asked.

“Where have you been?”

“Sir, I found something.”

Quintus was not in a tolerant mood. “What?” he snapped, “A backbone?”

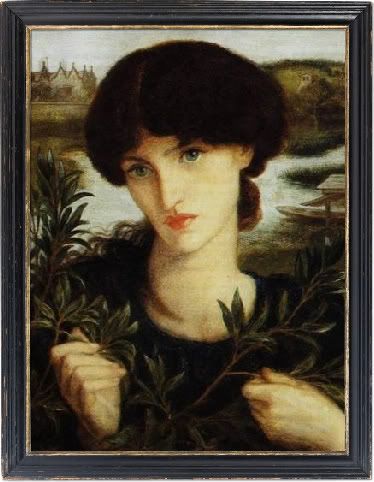

He raised his vine cane and saw the ill-starred runt flinch. “No, Sir – look.” The worst soldier in Second Augusta tried to show he had done something right for a change. The centurion and his second in command looked at what Aulus was pointing at and saw a bedraggled shape between two men unused to crying children. She was filthy, a little girl no older than six, bare feet cut by sharp stones and thorn bushes. Fresh blood ruined a once finely woven tunic of soft yellow dyed wool decorated by bright tablet woven braids. Someone had cared for her once with a mother’s love but now she was lost and alone.

Bleeding, Quintus noted two widely spaced puncture marks in her neck and could not tell what made them. Wilted oak leaves had been pinned to the front of her tunic with a bronze pin; it meant something to someone but not to any man of Rome.

He spoke quietly, repeating the word for friend in the language of the local tribe. His Celtic vocabulary could be counted on the fingers of one hand but, since his interpreter walked into a bog last full moon, he had to try. Nothing was ever found of the man, not much of a soldier truth to be told and as trustworthy as the skin on a bowl of cold barley porridge. The child’s eyes widened, perhaps at the terrible accent. Caius Lucius reached over and pulled a dried fig out of her ear, a sleight of hand trick that won a little more trust. He straightened the oak leaves and brushed some dried moss out of her hair with an uncharacteristically gentle hand.

“We should take her with us,” he said and waited. “She needs looking after, not even you would leave her out here with nothing.”

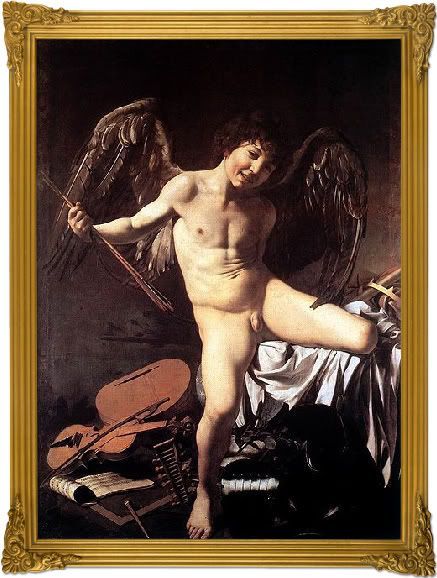

As Centurion, Quintus had the final word. He did not like children but wolves would not feel the same way. Little more than a mouthful, something was sure to eat her before night fell on a country that still rang with the cries of the dying. Only a few years before, the Iceni warrior queen of fell on Camulodunum and washed a beautiful town in blood. Londinium went the same way before Governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus marched back from victory against the druids to fight the final battle. Ten thousand men, the Legio XIV Gemina, parts of the XX Valera Victrix and any auxiliaries that could be found stood against a reported eighty thousand warriors. Second Augusta had been elsewhere on that bloody day, held back by a prefect who fell on his sword to end his shame.

Boudicca almost won but baggage wagons proved her undoing in the end. When the rebellion failed, thousands already lay dead on the last battlefield, many more put to the sword in the punitive raids that followed. For his part, Quintus did his duty and was not proud of it, drank to drown out the unquiet ghosts that haunted him. The last visit had been to a dirt poor village of three roundhouses where the only warrior last raised a spear twenty years ago and was now too decrepit to feed himself. They declared the place dealt with and marched on, against orders but nobody need know. He studied the child and refused to be rushed into a decision.

“It could be a trap,” he said. “This feels wrong.”

“No Sir,” Aulus gave a sloppy salute. “There was nobody about. I looked.”

That meant nothing but there had been enough death and he could not leave a small girl in the wilds. The marks on the child’s throat were unsettling. “This is a patrol of soldiers, not babysitters.”

Caius Lucius repeated his magic show, producing a fig from his superior officer’s left nostril. A deft trick but hardly dignified. “Julia will take her,” he said with certainty. He had been seeing a lot of the veteran’s widow recently, a childless, large hearted woman who had followed the Eagle for twenty-five years and now lived in the

vici that grew up around any camp. She deserved a chance to be happy.

“The child is your responsibility. You carry her. Enough time has been wasted.”

They fell into step with the economy of effort typical of one so long with the Eagles. The little girl perched high on the optio’s shoulders spoiled the effect, but he had always had his own way of doing things. “There will be freshly baked honey cakes, little one, and a very nice lady waiting for you,” he said, even though his passenger did not understand a word. “A kind lady to teach you a civilized language and who will love you like her own daughter. I might well ask her to marry me one day and then you will have to call me daddy.”

The camp loomed, looking even less imposing from the outside. Caius Lucius took his leave, peeling off from the column in the direction of the

vici.

Just as his tall, angular frame disappeared from view, the child turned around and stared directly at Centurion Marcus Flavius Quintus as if issuing a challenge. Her eyes turned black as pitch until he had to look away to clear the sensation that something crawled around in his mind. Quick as a traitor’s execution, the otherworldly stare vanished leaving only a guileless blue and the suspicion he had imagined it.

“You are dismissed”. The men did not have to be told twice and disappeared in search of drink and a dice game. Quintus tried to follow their example, thwarted by a newly made centurion who clearly had more noble blood and ambition than common sense.

“Sir, the Commander wanted to see you, as soon as you got back in.”

Quintus nodded, knowing that it was better to get it over with.

He walked to the Old Man’s office and waited outside until the officious little secretary said he could go in, stood to attention until given the at ease command. The Centurion Commander hated unnecessary paperwork and gave his officers more freedom than was usual; a strategy that worked because he knew when to rein them in and when to relax the leash. An iron-hard man with the direct stare of an eagle, his keen eyes missed nothing and he wasted few words on rhetoric. He scratched a signature on a wax tablet, shoving a pile of scrolls to one side and then looked up.

“Enjoying the sunshine while it lasts?”

“Yes, Sir,” Quintus knew it would soon start raining again. He ran a hand through cropped hair, tracing the scar where a British sword almost split his skull. “What are your orders?”

The Commander smiled, respecting someone who got straight to the point.

“I want you to take a patrol out at dusk. We lost three soldiers last night; two of them good, steady men who would never desert, the third’s barrack mates swear they saw him taken by shadows. No clear description except ‘shadows with teeth’. “Find out what is going on and stop it.” He paused, his smile genuine. “I want you to see what these shadows are and bite them back. If anyone can do that, Centurion, it is you.”

A rare moment of praise indeed, it was one to be savored in private. Quintus saluted and left

his commanding officer to draft another letter to a deceased legionary’s relatives. The Old Man handled this duty in person, carefully checked each man’s name and wrote every letter himself when he could easily have left it to his secretary.

Quintus walked back to his quarters and slumped onto the narrow cot, closed his eyes but found no comfort there. A parade of flickering images danced through a troubled mind and the nightmares would not let him rest. “Hell with it,” he poured himself a cup of wine, cursing at the taste which had not improved since the morning. Dusk fell quickly on a soggy little island which thrived on twilight tales of monsters and heroes who held off entire war-bands with just a small fruit knife. He would find the truth behind the disappearances, if it really was desertion or something far more sinister. Knowing Britannia, the latter seemed far more likely. Deserters deserted, they did not leave behind witnesses to swear that something had taken them.

“It is time to go.” Caius Lucius turned up all too soon. “Are you ready?”

“As ready as I will ever be.”

The optio grinned. “And you are as convincing a back street whore when she tells you she is clean and still has all her own teeth.”

They marched out in tight formation, the lowering British skies heavy with the promise of more rain. It brought more immediate problems that would not be solved by waterproof hobnails, no matter how well oiled. A strange legionary blocked the road by a milepost shrine as if waiting for them, a silent watcher who did not salute or move aside.

“You there,” he said, “answer me.” The senior centurion hit the soldier with his vine cane, unused to being ignored, wondered why Caius Lucius had just made a sign to ward off evil. He looked into a dead face, the pallor heightened by a pale grey wolf head tied in place above the man’s own. The animal’s pelt hung down over the brightly polished armour, its fur shining as if it recently brushed. As a rule, standard bearers did not leak blood from newly made holes in their throat, their skin cold as marble in a Caledonian winter. Their eyes did not snap open and burn with a death light. They did not snarl at a superior officer with fangs better suited to a wolf than a man. Shadows with teeth, the reports said.

“What the hell is that?”Caius Lucius said. The optio was a battle hardened veteran but inclined to listen to native superstition. They had both been on this island long enough to have heard the tales of Gods and monsters, shape shifting heroes or villains and Druid princes.

“Shut up and deal with it,” Quintus said as he drove his gladius into the nightmare.

Shadows with teeth still bleed, he thought, thinking of the lost soldiers as he faced what had taken them. He struck at the unprotected armpit, the only vulnerable spot in chainmail armor that covered both chest and back, drove the sword upwards towards a heart that had long stopped beating. The Gods were not with him that night and the sword blade missed its mark. He cursed as the thing that had once been a good and trusted soldier spoke to him.

“Join us,” it said. “Together, we will rule this island.”

“I am not interested.”

“Then die.”

A well thrown pilium hissed through air heavy with blood and smoke, burying itself in the standard bearer’s chest. "He is not interested in that either.” The optio ripped the javelin out, elbowed his superior out of the way when he did not move quickly enough.

Quintus felt the paralysis lift, forced himself to ignore every instinct to run. He rallied the men, their training holding, ordered them to finish this quickly so they could go back to camp. They had been well drilled and drew courage from the way their second in command screamed obscenities with a berserk rage that seemed more barbarian warrior than Roman. Jupiter- why would it not die? A little voice at the back of his mind suggested that it was dead already. He silenced the nagging influence, for how could you kill something that no longer breathed. Another wolf head loomed out of the night, pale lips snarling as it tore at a soldier’s throat. The man’s mates took that personally for he still them owed money from last night’s dice game. They stabbed out with their swords and hit the thing in the face with the bosses of their shields, fought as a unit as they had been trained to do. The first standard bearer went down at last, his dark heart pierced by more than one blade, the head still mouthing curses.

His companion stepped forward. “Join us,” it said again. “It is your choice. Join us or we will drain you dry.”

“Have a drink,” Caius Lucius uncorked a leather bottle, clearly regretting the waste, and threw it in the snarling face. He snatched a torch, shrugged at his commanding officer and explained. “Falernian, un-watered and it is the good stuff this time”. He might as well have thrown lamp oil; the wine’s alcohol content such that it caught fire easily.

The standard bearer blazed, screaming that it would rise again even as it burnt to ashes, sharp fragments of bone and links of fire blackened mail. The helmeted skull yawned wide, light from the dying flames making its canine teeth even longer. Quintus stabbed out with his sword, bit into an exposed throat and severed the head; did it all again as the voice of a long-ago drill instructor roared in his ear. Once learnt, never forgotten and the things that came out of the night marched onto his blade until his arm ached, his throat raw from shouting orders. When the last of the resurrected finally lay down again, he still did not believe what his eyes told him.

He ignored the dead, the way his men whispered behind him, their eyes wide and wondering. He was just over-tired, nothing more than that - all logical explanation failed; he simply stated the facts in his report and left the mystery to his superiors.

He walked in to his quarters, removed helmet and armor, splashed water over his face before he realized he was not alone. The tall woman finished reading a letter from a friend who had served his time in the Legions and retired. She did not hurry and seemed interested in every word, less by the details of a new baby and married life in general than the references to the old days of wine, women, battles and blood. She had changed her

calcei for gilded sandals of soft leather; the everyday shoes placed neatly by the door for no respectable Roman would do otherwise. No respectable matron would visit an army camp at night, but there she was.

The gates were guarded, but somehow she had slipped in unchallenged.

Someone should have stopped her.

“Lady, you should not be here,” he said, embarrassed by the state of his office.

Discarded kit and a pile of paperwork filled the small room, the wax writing tablets spilling over a low wooden table that still bore the remains of last night’s dinner. Senior officers usually shared a mess hall and had done so up until last month when a direct lightning strike ended that arrangement. Rebuilding work was slow, the novelty of eating alone for the first time in fifteen years still not worn off. Usually, his body slave did not leave dirty dishes lying around for the master to throw at him. He looked around for the little Brigantian who had once been a charioteer and could not see him anywhere.

“Vindex, where the hell have you got to? Bring more wine and another cup, a dish of good olives and some bread and oil. There must be some of that roast boar left.”

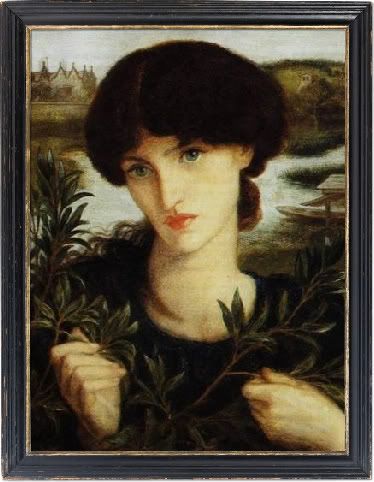

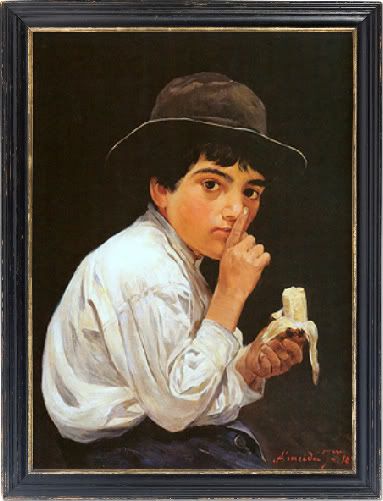

His guest smiled and dabbed at her mouth with a linen cloth. “Thank you, but I have already eaten.”A married woman by her dress, she came from one of the important families and used to being obeyed. Her raven hair had been arranged by a skilled ornatrix to fall to the face in an abundance of glossy, perfumed ringlets. Gold jewels shone at her throat, the face fashionably pale without the need for either paint or powder.

No white lead, however finely ground could equal the alabaster evenness of her skin. She wore a pale blue

stola of finely woven Tarentum wool, worn shorter than the under tunic to show she was rich enough to afford layers and further complemented by a wide ornamental border of Tyrian purple. Her crimson

palla draped elegantly over one shoulder, pinned with a gold fibula brooch that showed a cat stalking an unsuspecting sparrow. Quintus looked into her dark brown eyes and knew that she was the cat and he the sparrow, about to be pounced on.

She smiled. “The guards made a mistake; they tried to stop me. I hope you will not miss them too much, but I hate being told what to do.”

He tried to remember who had been posted to the gate that night. Aulus the Rat and another equally useless man: no great loss to the legion.

“Where is Caius Lucius?” He had not seen his optio all night, probably with one of his women.

“Was that his name? A fine looking man, he would adapt well to my world.”

“What have you done to him?” Quintus said, watching her eyes change color until they were almost as red as the palla.

“Nothing yet.” She drew him nearer, a deceptive strength closing like a trap. “I have searched for a companion for a long time, longer than you could possibly imagine.”

“What would your husband say?” He tried to pull away, unsettled by the sudden urgency in her voice, the longing on a beautiful face that no longer looked human. The naked hunger in her eyes unsettled him. “You are a respectable married woman and you bring shame on him and your family by saying such things.”

“Rome still had kings when I was young and those days are long forgotten. My husband, the poor sweet fool is no longer in any position to object; my surviving children are grown and share the Dark Gift. This is one of the Mysteries of Isis, Goddess and Mother to the golden land of Egypt.”

He drew his dagger, the oiled metal adding its own whisper to the background noise of rain outside and guttering oil lamps. She raised an elegant eyebrow, green malachite shadows part of her carefully applied make up, black kohl lines on each lid.

If he shouted, he could have eighty men to escort his strange visitor to the lock up, hold for questioning by the Camp Prefect and Senior Centurion Commander.

She smiled again, her pale face beautiful, terrible and still as death itself and the shout died in his throat. White arms embraced him, the scent of expensive perfume intoxicating. It almost masked the twin odors of blood and fear, but after a while, that no longer mattered. He lost himself in her beauty, the spell sealed by a kiss, and the dagger dropped to the floor.

A sandal-clad foot swept the weapon out of reach as she reached up to unpin the ornate brooches that held her wardrobe together. Expensive cloth whispered as she peeled tunic and under tunic away from a body made for making love. He smelt the essences of lavender and rose as she drew a pair of ivory pins out of her elaborate hairstyle and let the ringlets cascade over her naked shoulders. Both seducer and predator, she had the confidence of a woman who was comfortable in her own skin and not afraid to show it off to strangers.

“Do you like what you see?” she asked. Soft as a ripe sun-warmed peach, skin rippled over lithe muscles more suited to a panther than a noble born lady.

Quintus could not answer, drawn to her in spite of his instincts and unable to think, let alone speak. It had been almost a year since he was last with a woman and an urgent drumming of pure lust filled his head as they came together. Cold lips caressed him, sharp nails leaving bloody trails down his back that were quickly licked away. He could feel the thunder of blood in his ears as she moved under him with a sinuous, eel-like grace.

For a short time, they were as one, a single being united by animal lust and she whispered to him, speaking of future glory and power.

“All this can be yours,” she said afterwards, her beautiful face shining with possibilities as yet unspoken. “We can be together forever and our love will never die or grow old. Accept what I can give to you, my love, for I offer eternity.”

“You speak in riddles,” Quintus reached for his wine cup, seeing the familiar hunt scene of hounds and a wild boar at bay. A gift from his favorite uncle, the figures pressed into the wet red clay and modeled by an artist who really knew their business, but the animals had never chased each other around the rim before. Lithe bodied hounds snarled as a man with a spear prepared to strike.

The huntsman was an unexpected addition, never before seen, and for some reason looked like the camp Prefect. The boar had a strangely human face – his own. He blinked and the new additions faded away, dogs and wild pig kept their stations as the artist imagined them. Something occurred to him then, the memory of the puncture marks in a small throat.

“What did you do with the child?”

“My optio took her to a friend.” He did not bother to hide his surprise, had already guessed she had something to do with leaving a little girl alone in the wilds. Her silvery laughter confirmed it.

“Her name is Rigohena, youngest daughter of a minor chieftain of the Trinovantes not fated to get any more important.”

“You make no sense.” he said.

“I warned him not to interfere but the British have always been a stubborn people. A proud warlike nature and a childish sense of their own place in things; you know what they are like. He objected when I took his child away from him. He died and his village lies in ruins, his warriors and women just as dead as he is. I spared no one I found there, save the chieftain’s pack of hunting hounds. They will eat well tonight.”

She did not seem like someone who took no for an answer. Long fingers brushed the pommel of his gladius; half drew the sword from its scabbard before laying it down again. She had no need for weapons. Quintus saw the flash of iron in her eyes and knew that anyone who crossed her, Roman or Celt, would find their way to their respective Gods sooner than expected. The chieftain was dead, better not to ask how.

“It would not be right to turn someone so new to the world. There are rules even for Higher Ones such as myself but I can still see through her eyes and whisper to her in the darkness. When she is old enough to make the choice, we will meet again. That girl has an important part to play in the history of this island.”

And she would guide that destiny and seek to use it to her own advantage.

Shadows with Teeth did not seem to care who they fed on or exploited, it was in their nature like wolves and any trace of humanity had long since fled.

“Who are you, Lady?”

“My name is Julia of the Bloody Hand.” A hunter who killed without mercy, took what she wanted and moved on. “I offer a chance to live forever. Every patrol might be your last for, whatever they might say back in Rome, the tribes are not yet fully pacified and the great Suetonius Paulinus is too busy building his career to care what happens next. Their Goddess of Victory; Andrastre may send them another Boudicca to sweep the Eagle back into the sea. Rigohena was born to be a druid priestess but she shares the same spirit as the Iceni warrior queen. I can guide her on the path of blood and it will be glorious. If you take what I offer, you can stand at my side and share the spoils.”

She touched his face, a caress that lingered long after she had moved her fingers. “You will never grow old or know pain or illness and you will never find a grave on this miserable little island.”

“I am a soldier, Lady. It is my duty to take that risk.”

“You will die and be forgotten,” she said.

“If that is my fate, so be it.” He shrugged, seeing the blood lights fill her eyes, replacing the chestnut brown with crimson. She smiled again, white teeth glittering in the lamplight as she bent her head to his throat and kissed him; the lover’s caress given an edge by the press of sharp teeth against his skin. Her voice took on urgency, hypnotic.

“Then I make the decision for you. Eternity is painless, I promise.”

She never got the chance to prove it, interrupted by a buccina greeting the dawn. A second trumpet added its voice to soar above a camp that would soon wake to duty.

Julia hissed like a frustrated cat cheated of its sport. She paused, as if torn between escape and getting her own way.

Centurion Marcus Flavius Quintus of the Second Augustan Legion watched her drift away like smoke from a dying watch fire. All that remained was a pair of long ivory hairpins and the stalking cat and sparrow fibula, the lingering scent of perfume and the promise she would return to finish what she had started. There was a little girl in the

vici camp groomed as the next Boudicca, leader of a rebellion planned by something that had not been human for centuries. Quintus did not expect to live long enough to have to kill a child.

In Britannia the nights came all too soon and seemed to last forever.

* * *Rebecca Sian Pyne is a freelance writer and science journalist from West Wales with a strong interest in prehistoric to medieval history. Published fiction has appeared in:

Albedo One, Delivered, Neo-opsis, Tainted - Anthology of Terror and the Supernatural, Star Stepping Anthology, Pen Cambria, Hungur, Crimson Highway, Orphan Leaf Review, Apollo's Lyre, Twisted Tongue and others.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?I live in area well known for its sightings of ABC’s ('Alien' Big Cats) and some of my fiction draws on Welsh history and folklore. Membership of

Prytani - a Celtic re-enactment group has been useful for writing fiction set in Iron Age and post Roman Conquest Britain. The basic idea behind “Centurion’s Choice” came while filming a documentary on the Boudiccan Revolt of AD 60/61. Some characters are loosely based on people met during that exhausting week in 1994 when we worked with a Roman Legionary group – The Ermine Street Guard. The idea went cold for years until I read about another less well known uprising in AD 69. What if someone (or something) engineered a similar revolt? As our druid used to say to the audience at the end of every battle – “Let the dead arise!”