Cave Painting

by Marko Fong

Below the Medici chapel, the smell of mildew coats the darkness. The prisoner believes that he is hiding here. The fact that all the servants who provide the prisoner with water, food, and clothing work for Duke Allesandro de Medici, the man he is trying to evade, says otherwise. When it comes to simple matters, artists are notoriously oblivious. This is no hiding place; it’s a dungeon and a most peculiar one at that.

There are no restraints and no beatings. They even feed the prisoner well—a breast of chicken cooked the day before with three cloves of garlic, bits of bread that remain spongy inside, a roasted onion. One morning, he is given a piece of something called a “banana.” It should dawn on the prisoner that this is a hint from Alessandro himself. Any fruit as exotic as a banana could only have come from the Duke’s table, a sure sign to the normally observant that the Duke not only knows exactly where the prisoner has sought to hide, but also proof that the Duke controls his confinement.

A young girl brings the prisoner fresh water each morning and occasionally he gets a goblet of a red liquid that is more wine than vinegar. Even some of the Duke’s soldiers who served him during the Medici’s nine month siege to retake Florence from the Republic do not fare this well. This hardly appears to be punishment for a man who designed the fortifications that prolonged the siege into the summer of 1530. Alessandro’s advisors privately wonder if the twenty-year-old Duke has yet acquired the toughness to be a true Prince.

‘Do you remember old Niccolo?” they whisper.

“Yes, if he were still tutoring the Duke, he would know better. If only Niccolo were still alive,” they agree.

For centuries Machiavelli’s subtlety will continue to elude ordinary minds. Three years after his death, he is still thought to be an advocate of raw power. Only a few individuals have ever seen the treatise, the document that makes it clear that Niccolo, himself the one-time head of the Florentine militia, never saw power as something that should ever be “raw.”

This is what makes it a dungeon. The room is big enough. It’s just that it has three small grates instead of windows. They limit the prisoner to two medium-sized beeswax candles each day, about three and a half hours of the dimmest of light. It’s never quite bright enough to see color or beyond the roughest of shapes. Alessandro has no interest in torturing the man. He tortures the artist inside the man with just enough light to tantalize and frustrate.

Alessandro demonstrates his subtlety through another gesture. He orders that the only persons with whom the prisoner may have contact must be female. Will it be harder for this prisoner to live without sunlight or without male companionship? For the first three days, the prisoner is given paper and charcoal. Even in the dim light, he draws a bit each day. On the fourth day, Elsa, the girl who brings his chamber pot, is instructed to tell the prisoner, “I’m sorry sir, there is no more paper to be had. The people of the city used it to keep warm during the siege. All the charcoal was used to dry mortar for one of the fortifications. My father tells me that the republicans never valued paper or charcoal beyond that.”

The prisoner squats against the warmest of the walls as he contemplates this intensification of his solitude. He spends most of his day lying on his back with his eyes open. He once spent the better part of four years in this exact position, but that was as a free man. He stares into darkness towards the ceiling, but he doesn’t need light to see what’s above the ceiling of his cell.

No one remembers the individuals whose bodies rest inside the tons of polished marble above except for the fact that they were once members of the Medici family. In two generations, no one will remember even that if it weren’t for the paired statues that decorate theses tombs. Atop one, two statues represent morning and night. The other serves as the base for a pair that depicts sorrow and triumph. Two of the bodies in the tombs are women, but all of the statues are male. The ripples in their musculature flow with the light. From certain angles they actually seem to be in motion. The prisoner sculpted those statues. This is the one building in Florence that the Medici would never storm.

Below the supine prisoner, forgotten bodies, victims of the plague from a century ago, wait to be carried away by the currents of an underground river. The river changed course, though, and the bodies never moved. When Brunelleschi started construction on the basilica in 1408, they forgot that the bodies were still there. Some feared that this placed a curse on the Medici family.

Before the prisoner went into hiding, he sent a message to the Pope, himself a member of the Medici family who as a boy dined with the prisoner at Lorenzo de Medici’s table several times. “Your Holiness, please grant me a pardon so that I may finish my sculptures to the glory of God. I played no active part in the resistance to your cousin and his army.”

The prisoner knows that the first part is a lie. His sculptures don’t glorify God as much as they revel in the perfection of the human body, in particular the male torso. He gambles that the Pope remains a Medici first and God’s representative on Earth second. The other part is more debatable. He helped to design the fortifications, but he left the city before they could be completed, only to return in the midst of the siege.

The servant, only eleven years old, who brings the prisoner his meals reports personally to Allesandro twice a week. One would think that the new Duke would have more pressing problems. For one, what will he owe the King of Spain for his assistance in retaking the city? What allegiance will he owe his own cousin the Pope? Whom can he trust to help him restore the wool trade to the city? The only men who know how to finance the caravans and get Tuscan wool to port cities are the same men who betrayed the family. After a nine month siege of Florence, food remains a problem for most. Only the very brave dare to walk near even the main square after the sun goes down.

So why does the Duke take such an interest in a single artist who has either sought refuge beneath the Medici Chapel or been maneuvered there? To understand that, one must know the history of the project itself. Cosimo de Medici started the building itself five generations ago, but it was Lorenzo who saw its possibilities as a monument to the Medici’s memory and power, memory and power being more or less identical as a historical matter. In 1471, a Sicilian cotton trader came to Florence seeking to expand his business to the wool trade in winter. To smooth his introduction to Lorenzo the Magnificent he brought along a gift, drawings of the pyramids of Egypt.

The gift inspired Lorenzo, but Florence did not have the stone or the laborers for pyramids. The best of both went to the duomo, the cathedral. Even Medici ego at its grandest didn’t dare compete with God.

Instead Lorenzo bypassed God by summoning artists to his court. Eternal beauty would substitute for sheer mass. Only Lorenzo never anticipated the possibility that thousands of masons, the most independent craftsmen of all, would be far easier to find and control than the whims of a truly gifted artist. It was Lorenzo who had discovered and courted the prisoner. For three years, the prisoner dined at Lorenzo’s own table until 1491. It was during that time that Lorenzo persuaded the artist who would become the prisoner to redesign what Brunelleschi had started.

Lorenzo died in 1492. First came Savonarola; the first return of the Medici followed, then more war. Between those events, whenever he needed patronage, the prisoner worked on the chapel.

As a student of Machiavelli, Alessandro understands the importance of the project and the prisoner himself. It was Niccolo who told him that it was actually more important to appear powerful than to be powerful as a ruler. Continuing work on this project would be a sign to all of Italy that the Medici were fully in control of Florence and certain of their future. He thus has prioritized persuading his prisoner to return to work on the chapel in earnest. Perhaps only Machiavelli himself would understand just how Alessandro intends to manage this.

The girl stands before Alessandro while he dines. Her body still looks something like a boy’s, but her face is pretty, feminine, and well-defined like Roman sculpture.

“What can you tell me about the prisoner?” he asks.

“Well, there is one thing that I have never seen him do.”

“What is that, child?”

“He never seems to pray.”

The Duke does not react visibly, but he wonders how the man who painted the most celebrated work of religious art in Europe can spend his entire day in the darkness and never think to pray.

Two days later, unknown to the Duke, the girl brings the prisoner a child’s wooden top. She spins it for him on the bit of floor that remains flat stone. The top wobbles after just a few seconds, it is not well made, but the prisoner does not want to hurt the girl’s feelings. It is after all a gesture of kindness as imagined and executed by a child.

After she closes the door behind her, he plays with the object for several hours as he tries to imagine the planets and sun as they spin around the earth.

One afternoon, she sits on her side of the door and listens for the plop of the fat part of the top as it dies on the stone, then the whirr a few minutes later as it hits the floor again. She had once heard a story of a place in the world where men pray by spinning a kind of wheel. She is helping to save the prisoner from eternal damnation.

A few days after that she brings the prisoner his supper and he motions for her to watch. He takes the top and launches it to the flat part of the stone. This time it spins in near perfect balance, barely moving from its spot on the floor. It even whistles. After the second time, he hands it to her and lets her spin it for herself. The girl—she told him that her name is Francesca two weeks earlier—squeals with delight as she admires the possibilities of a simple bit of wood. The prisoner then gives her back her top. She thanks him profusely, then closes the door that lets in what little light gets into the cell beyond the two candles a day.

Once outside the door to his cell, the girl sees that the prisoner has used a small bit of rock to cut lines into the fat part of the top. He has known exactly where and how to score it. Only then does it occur to her that he has managed this feat in near complete darkness. She shakes her head in admiration, but doesn’t tell the Duke anything about the incident.

The prisoner still has no idea when he will be able to leave this hiding place. His days lengthen. He has begun to converse more with this child, Francesca, as she brings him his meals then returns to pick up his wooden bowl and tin cup. At first the conversations are simple. He asks her about the top, about her family (her father is dead, she was taken in by the staff of the chapel as a favor), about what she has seen or knows of the world beyond Florence.

“Does anyone know that I’m here?”

She nods.

“They do?”

“I know that you’re here and those who tell me my duties.”

“Yes, of course, those who work in the basilica must know, but anyone beyond that.”

“No sir,” she lies. After all, the Duke has sworn her to secrecy.

He nods at her answer, not even pausing to consider its implausibility.

Another day, he asks her, “Do you know who I am?”

“Not really, sir.”

He nods at this, too.

She then asks, “Should I?”

“It’s better that you not know. If anyone asks you, you could then deny it. Do you know why I am here?”

“No, signore, only that I am to bring you your food and drink and whatever else you may need.”

This is mostly true, but even Francesca knows that it is in some ways a lie. After she leaves the cell, she crosses herself. As the days pass, the time elapsed between bringing the prisoner his meal and coming to pick it up shortens. He takes even longer to eat; it’s just that their conversations at both ends of this process have lengthened to the point of nearly meeting in the middle.

One morning she asks the prisoner, “What do you miss?”

“What do you mean?” he asks.

She did not expect to be answered with a question.

“If I were in this room, I would miss the warmth of the sun,” she says.

“I miss that, yes.”

He takes a bite of bread. He is an old man, beyond fifty. This is the first time she has noticed that he has all his teeth. How does one manage that?

“I would miss the market.”

“That I don’t miss,” he whispers.

“I would miss the smell of trees.”

The prisoner looks directly at her. The door remains halfway open as a triangle of light comes into his cell. He whispers.

“I miss the light. I miss my drawing.”

The girl says nothing, but nods. If only she could bring him extra candles, but she knows that is strictly forbidden. The head of the kitchen himself counts the candles at the end of every day, just to make sure that the prisoner gets no more than the Duke has allotted. She knows as well that she is forbidden to bring the prisoner charcoal, brushes, paints, or paper. She holds the top beneath her dress and feels the edges of the lines sculpted into its surface. Each the exact depth needed to rebalance the top, some of them are so fine and perfectly scored that one can only see them in bright sun.

Two days later, the prisoner discovers an extra wooden spoon with his bowl. He tries to give it back to the girl at the end of his meal.

“Oh, no sir, I would be punished if I brought back more than one spoon with me.”

The prisoner takes the spoon and hides it under a loose stone in the wall. The next day, he finds another extra spoon with his meal.

“When I was a little girl, my mother punished me for ruining my dress,” she tells him.

The prisoner shows no interest, but the girl continues anyway.

“Some boys had lit a fire the night before and put it out with water. I played with the burned sticks the next day. It left marks all over my skin and clothing,” her voice is high, sweet, and even more childlike than usual. It is as if she’s talking to a friend her own age.

The prisoner stares at the girl in the dim light. For the first time, he has seen her possibilities. After she leaves, he holds the wooden spoon to the flame of his candle and lets it burn, turning it into charcoal. Just before his last candle burns out, he smudges the wall with the charcoal.

In his next supper, he finds two more wooden spoons. He realizes that the girl has thanked him for fixing her toy top. Before she leaves, he tells her,

“You know, there is one other thing I miss.”

“Just one?”

“When I was much younger, I met a sailor from Genoa.”

“You miss him?”

“No and yes. I do miss having others to spend time with, but he is not what I miss.”

She nods.

“He told me that on one of his trips he had been to the end of the ocean where they found an entire new world. Have you ever heard of such a thing?”

The girl shrugs.

“There are lands on the other side of the ocean, undiscovered places,” he continues.

“Why?”

“What do you mean by why?” he asks.

“Why would you miss places you’d never visited?”

“There are people there. They have their own history, their own way of seeing the world.”

The girl does not respond, but the prisoner continues.

“They call them the Taino and everything they do is different from us.”

“Do they have the same God as us?”

The prisoner shakes his head. “I don’t know. I didn’t get the chance to ask.”

He knows that it was because he didn’t care to ask, but he assumes wrongly that the girl doesn’t suspect. He also does not tell the girl the most exciting thing he remembers about the Taino. There are Taino males, young boys even, who happily do things that would fill a Christian male with shame. The prisoner has thought for years about these delicious possibilities. He remains confident that the girl will not press him for details about how he came to meet this Genovese sailor. This mention of the Taino is as close as he can come to telling her about what he misses most beyond the light.

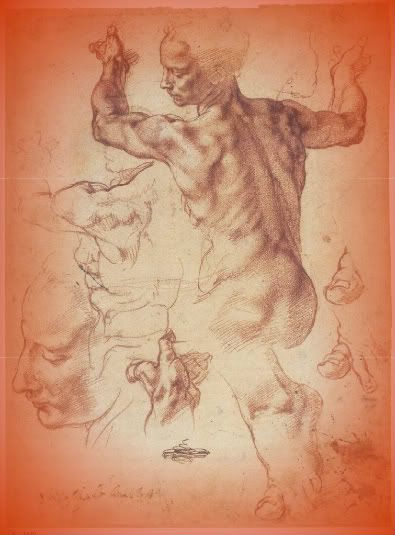

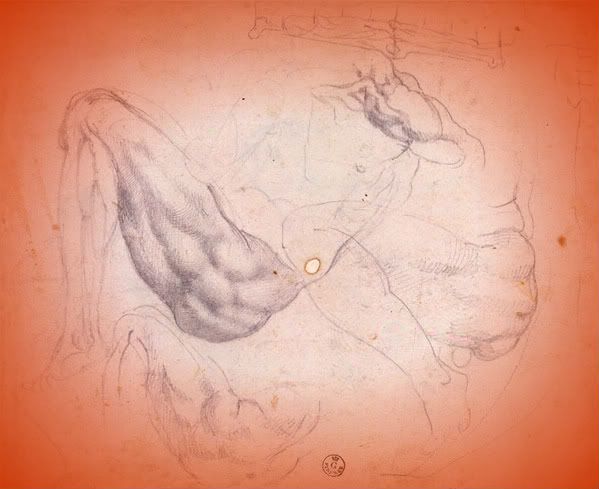

It is, of course, the darkness itself that brings out these thoughts of the flesh. When one cannot see, one becomes uncommonly aware of touch and skin. A few days later, with the limited candlelight available to him, the prisoner begins to draw on the walls. The first things he draws are parts of men. He draws the muscle of arms, the twist of a torso, the tension between balance and motion of a perfect calf. He is drawing body parts, but the parts are entirely disembodied. When the light from his candle runs out, he masturbates to his own drawings.

Is he going mad in his own hiding place? Is the drawing helping or hurting his capacity to pass time here? When she brings his food, does the girl even notice these drawings? He has taken care to place his drawing in the part of the room that does not get direct light from the half-opened door. The girl herself does not appear to be the inquisitive type. She barely looks around when she does her duties or when they talk. In the meantime, the walls fill with drawings. He tells himself that she could not suspect what he’s been doing, yet she keeps bringing him extra wooden spoons.

For the first time in a month, Duke asks the girl to report to him personally about the prisoner’s progress. The girl stands before the Duke and marvels at the smells and shapes of the items on his dinner table. He has been unusually kind to her in their meetings. Each time, she has grown less afraid in his presence.

“How is the prisoner faring?”

“He continues to eat well, Your Highness.”

“But you know that I am asking you more than that.”

She nods.

In the last week, the citizens of Florence begin to wander the square later and later. The market has dozens of new vendors. Some of them now offer special prices on food that is about to spoil. It is no longer enough just to sell bread, even some of the poor demand that it be fresh and entirely free of weevils. The Duke, however, remains unpopular. No new work is being done on the basilica.

“Your Highness, the prisoner speaks to me now, quite regularly.”

“And what does he say?”

She hesitates, then answers, “We talk about the things he misses. Once, he told me about new worlds in lands beyond the ocean. I once tried to tell him about “oranges.” Is that what you let me eat the last time I came here?”

The Duke points to the remnants of a sliced orange on the table and motions for her to take another piece. The girls eyes widen with excitement, she does not even attempt to refuse. One visit, he let her taste a fruit that looked like it would be even more delicious, ripe, red, round, something called a “tomato.”

She had been disappointed. It was nowhere as sweet as its appearance suggested and it was filled with yellow seeds. It too had been brought from some strange and exotic place. She thanked God that the people of Tuscany would always have better things to eat. Were these tomatoes from the same new world that the prisoner had mentioned? Only savages would think to eat such things or people in a city at the end of a nine month siege. It was all she could do not to spit it out.

“He hates the darkness, Your Highness.”

“But he is keeping his mind in that darkness?”

“He is talking more than before. He seems a bit more nervous in my presence, but he remains understandable and calm.”

For a moment, she thinks to ask the Duke if she can bring the prisoner more and bigger candles, but then reconsiders.

“You will tell me if he begins to lose his mind?”

“Yes, but how much longer will he be there?”

“Until we come to an understanding.”

“How will I know when he does?”

It has not until now occurred to the Duke that the girl has an intelligence of her own. He takes a sip of wine from his Cellini goblet then motions to a lesser cup at the table, offering the girl red wine. He is only a few years older than she is. He wonders if she has any inkling that they are so close in age.

“God will tell you, my child.”

He has no idea why he has said this, but the answer satisfies her curiosity.

One evening, she brings the prisoner new clothes. He slips behind the door to take off his old ones. She is surprised by his lack of modesty, but he is a very old man. Perhaps he cannot imagine that she would care to look, even out of curiosity.

“Is it September yet?” he asks from behind the door.

“The wool was loaded on to the caravan last week. The merchants are telling the farmers not to slaughter too many lambs before winter for meat. Their wool will be too valuable next year.”

As he puts on the new top and pants, the prisoner instinctively hands her his old clothes. She steps towards the edge of the door and for the first time she notices the drawings. She gasps.

The prisoner is all too aware of what she has seen.

“They look so real!” she exclaims, “How did you do that?”

“It’s what I do.”

Without asking, the girl opens the door all the way and a comparative flood of light fills the cell. It is the first time the prisoner has seen his own drawings this clearly.

“They’re beautiful, but why just parts of bodies?”

He does not answer her question. He, of course, knows the answer, but the prisoner cannot possibly tell an innocent, Because that was all I needed to serve my fleshly purpose.

He remembers Savonarola too well and the winter day on the seventh of February 1497 when they burned his paintings. He watched the canvas curl at the edges in the heat and bits of his pictures break away from the fire, paintings of body parts floating into the night sky in the name of all that is holy. Suddenly, the connection between that pain-filled memory and the drawings on this wall becomes apparent to him.

As he admires his own drawings for the first time, this too dawns on him. This is the most beautiful work he has ever done. These are sketches that are somehow perfect in their state of being unfinished. They are not calves, and torsos, and hands at all. They are unedited expressions of pure desire, straight from his imagination, free of any thought of God.

“It’s just what I was able to draw,” he tells the girl.

It is the girl’s turn to surprise him back with her next question, “Are these those people? Are these the Taino?”

The prisoner’s mouth hangs open. She has seen in a matter of seconds what he the artist had never considered, yet….

He nods, even though he himself has never actually seen the Taino.

“So these are the people who have never met God.”

She doesn’t think about it until she hears herself say it and the very thought makes her shudder. The prisoner wants to assure her that’s not the case, but the drawings speak for themselves. He cannot deny it.

The girl turns away from the drawings.

“I can’t look. I mustn’t look any more….What have I done?”

Her eyes fill with tears. Without thinking about it, the prisoner puts a hand on her shoulder to comfort the girl.

“It’s not finished. You will see….let me show you in a couple days.”

As soon as the girl closes the door behind her, the prisoner lights two of his candles and hurriedly begins a new drawing on the wall directly across from the door. For the next two days, the girl barely opens the door when she brings him his food. She does not look at him, she does not look in the direction of the walls, and she says nothing.

On the seventh day of this, as soon as she drops his bowl inside the door—this time with just one wooden spoon—the prisoner is ready.

“Please, Francesca! I want you to see this. I didn’t mean to terrify you the other day. I would never do such a thing on purpose.”

She turns away but does not completely close the door.

“It’s all right. I saw nothing. It never happened.”

“Please, I ask you open the door and have another look.”

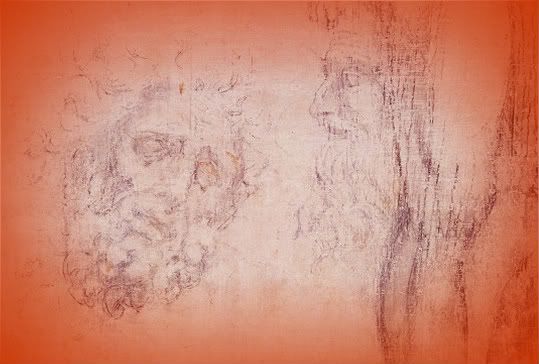

She does not respond immediately. The prisoner will not take “no” for an answer, though. In one motion, he pulls the girl inside the cell and pushes the door completely open. She wants to scream, but somehow doesn’t. The cell fills with light and before her on the opposite wall is a near life-sized portrait of a resurrected Christ.

“It’s even more beautiful,” she murmurs, then drops to her knees to pray.

“So, the Taino have seen God too now,” says the prisoner.

He doesn’t believe any of this, but the prisoner has seen that it would be a sin to hurt such a kind-hearted girl. He now sees the whole tableau, the two walls, for this first time.

When he was painting the ceiling of St. Peter’s, one of the workmen had come to him with a story. He had been in the north and heard of a most curious painting done on three pieces of wood by a German named Bosch. Where the painting at St. Peter’s would be the story of Man and God, from the creation onwards, Bosch had included hell itself and all the dangers of temptation. The artisan related what he knew of this northern painter then asked a simple question, “If this was to be a portrait of all of man’s history, why had we left out the devil?”

The artist had a simple answer at the time; “The Pope had not asked for it.”

Indeed, he had argued with Pope Sixtus about the tableau not precisely following the order that he had learned himself as a child. The Pope had never said it, but he had not commissioned a holy work of art at all. The point of the paintings on the ceiling had been far simpler than that. The stories told in pictures were there to remind visitors that the Pope spoke directly to God. The paintings confirmed the Pope’s authority, not God’s.

When the man had asked him, “But what did God ask for?” the artist replied almost without thinking. “The Pope will tell me whatever God asks.”

He had finished the commission for the ceiling shortly after that, in 1512. As he looks at this new painting, done without colors, done without even light, the prisoner realizes something else. This is the shadow of what he spent four years painting in Rome.

The girl gets up, picks up the prisoner’s bowl, and leaves without closing the door. The prisoner shuts it himself after she leaves, but he draws on the walls of his cell no longer.

She reports to the Duke three days later.

Before winter comes, the prisoner is surprised to receive a full pardon from the Pope, Duke Alessandro’s cousin. He leaves his hiding place and sends a message to the Duke.

“Now that I have returned to Florence, I wish to finish my work on the basilica but will do so on one condition.”

When the Duke gets the news, he does not hide his joy. He has won. He sends a message to the artist to come to him in person to explain his one condition. After the introductions, the two men share a banana. For the last two weeks, the artist has spent entire days in the middle of the square, his shirt open, reveling in the sunlight even as winter approaches. He has also managed to slip away with two young men he meets in the square to play in the darkness. Oddly, in these moments the artist finds himself thinking of the girl. It is the only time in his life when he will think of a girl while having sex. He does not think about her in a carnal way, it is just that he sees her face whenever he closes his eyes during these trysts.

“So, what is this one condition?” The Duke gets to the point.

“There is a room below the chapel. I want the entrance sealed for all time and no one is to ever look inside. I will do the masonry work myself.”

“It’s done,” says the Duke as he unwittingly completes the artist’s revenge.

He will continue to work on the chapel, but no one will see his greatest work, at least not until the world is ready for it. The Medici will never get that kind of immortality from his hands. The artist works for three more years off and on with the sculptures and the entryway for the basilica, but he never finishes. Most of those there have no idea that the man had just months ago been a prisoner in this very building.

One day it occurs to him that he may die here working on projects about which he no longer cares, all to ensure the memory of a family whose descendants after Lorenzo he does not respect. One day, the artist slips away, some say with the help of a young woman who walks him out of the city and helps him to hide at a sheep ranch in the hills.

The artist returns to Rome and finishes one last painting at the Vatican, a picture of the Last Judgment behind the Sistine Chapel. He dies a few months after that. When he dies, no one knows about the secret rooms deep within the catacombs that he has filled with drawings done by candlelight so dim that ordinary people can barely see the walls, much less draw on them. The artist himself set the stones closing off the entrances.

Duke Alessandro dies a few years later before turning forty. His enemies lure him into what he thinks is a rendezvous with the wife of a nobleman. Just as he removes his pantaloons below his calves, knife-bearing assassins take him by surprise and murder him.

In 1976 a workman, who claims to be a descendant of a woman who once knew Michelangelo, goes to fix an electric line just beneath the Medici chapel and drills a hole in the wall. Much to his shock, he discovers drawings at the end of his flashlight beam. The art critics call it “doodles” even if they are almost unquestionably Michelangelo’s doodles. Others, though, see something else. One expert, a Bosch specialist, insists that these aren’t unrelated drawings at all, that there is an eerie coherence to them. It is, she says, “as if Michelangelo created modern art before modern art was possible.”

Some have heard the stories about the rooms, actually more like caves, beneath the Vatican. For instance, there is a mad street artist in Rome who will either tell you the story or draw your portrait on the sidewalk in chalk for just five Euros. Having just come from Florence, you tell him that you’d like to see these caves yourself to see what else Michelangelo might have imagined. You’d pay anything to see what he drew there.

“Signore, you don’t have to visit these rooms to see them. I have never visited them myself.”

You laugh and begin to walk away after giving the man two Euros for his story.

“Signore, if you want to see these rooms, all you have to do is lie on your back in a completely dark room and open your eyes.”

Editor’s Note:

See more of Michelangelo’s sketches from the Medici Chapel here.

* * *

Marko Fong lives in Northern California and recently completed a collection of short stories, Inventing China. His most current publications include Grey Sparrow Journal, Summerset Review, and Kartika.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

Cave Painting was inspired by a visit to the actual room below the Medici Chapel many years ago and how "modern" the sketches there felt. I think of it as more "alternate-history" than historical fiction. I look at alternate-history as what possibly happens when reality blinks.

0 comments:

Post a Comment