The Triumph of Deborah by Eva Etzioni-Halevy ★★★☆☆

“Two women were standing on high places, shielding their eyes from the blazing sun with their hands, peering into the distance in search of messengers from the battlefield. Each knew that her life depended on the outcome of the battle; but their lives depended on opposite results.”

One of my favorite aspects of the biblical account of Deborah—and I have many—is the complete indifference of the writer to Deborah’s gender. She is a prophetess—she is the wife of Lapidoth—in her song of praise after the defeat of King Jabin’s Canaanite army, she sings of herself as a mother in Israel. This is the full extent of biblical commentary on Deborah in terms of her sex; the rest of Judges 4:4-5:31 shows the qualities—charisma, faith, decisiveness, tranquility—that made her such a powerful and enduring figure.

The same cannot be said of Eva Etzioni-Halevy’s re-envisioning The Triumph of Deborah. This novel focuses on three women—Deborah, Judge of Israel: Asherah, daughter of Jabin and wife of Canaanite commander Sisera: and Nogah, illegitimate daughter of Jabin by an Israelite slave—and to a large extent, it is a novel about being a woman in the ancient middle east. Nogah, who is arguably the character least affected by her gender, suffers an attempted rape before her royal parentage is revealed. Princess Asherah’s life is defined by the men around her, not only externally, through her royal father and heroic husband, but through her own self-perception:

…she had been aware that she outshone the king’s other daughters in her beauty…[y]et she did not bask in her looks, either, because there was no man nearby whom she would have wished to savor them.And earlier, when she met Sisera for the first time,

...it was as if the king’s youngest daughter emerged out of a deep slumber and, for the first time in her life, became truly and vibrantly alive.

Perhaps it is to be expected that two young women surrounded by powerful men will always be defined as this man’s daughter or that man’s wife, but I was surprised by the degree to which Deborah is also defined by her gender. In the novel, everyone from the enemy Sisera to Deborah’s own husband Lapidoth considers a woman unfit to rule:

Then [Sisera] favored her with a hard-edged look and chilling words: “It was not wise of your leaders to appoint a woman to speak to me.”

The prophetess would not allow him to slight her, but she had no wish to enrage him either. So she said in an appeasing voice: “I am the leader myself, even though I am a woman.”

He glared at her and gave a snort of sneering laughter. “A woman leader? A woman should extend a helping hand to her husband, which is what you should be doing now, instead of interfering in men’s affairs.”

Here, Sisera is clearly meant to appear brutish and unenlightened. But a few paragraphs later, Deborah herself acknowledges women’s minds as inferior to men’s, justifying her leadership on account of feminine emotion, and defines female rulers in terms of their male relations*:

In a further attempt to placate him, she said, “Men have the wisdom of the mind, but women have the wisdom of the heart. They are mothers of sons*; therefore, they understand how crucial it is to reach peace...”

But the crowning moment in Deborah’s definition as a woman before a Judge of Israel is Etzioni-Halevy’s interpretation of Barak’s request that Deborah “go with” him before he leads his men against the Canaanites:

…When they had all gone, [Barak] sat there for a while, regarding her boldly from under his half-lowered lids and thick eyebrows. Finally he said, “I demand a reward from you for my obedience to your high-handed command,” and his gleaming eyes clearly indicated the reward he had in mind.

And so Deborah, Judge of Israel, becomes one of the womanizing general’s conquests.

This opens to door to the real plot of The Triumph of Deborah; it is not, like Judges 4-5, the story of the battle to drive the Canaanites out of Israel, though the war and struggle for peace afterward form the frame for the novel; it is a love triangle. More specifically, a love quadrangle. Deborah and Nogah both love Barak; the latter loses her virginity to him, the former, her marriage. Barak loves the beautiful captive Asherah. Asherah loves her murdered husband—whose killer, Jael wife of Heber, also lusts after Barak.

It is in this heavily emotional, heavily sensual environment that Etzioni-Halevy shines. The dissolution of Deborah’s marriage is frustrating, heart-rending, and wholly familiar to modern readers. Asherah is a very human young woman, still reeling from the loss of her long-desired husband and struggling against Barak’s brutish advances. Nogah, in many ways the most independent of the women, confronts timeless choices—love vs. security, sexual attraction vs. companionship. This emotion and sexuality is set against a background of vivid historical detail, and the characters weather situations that feel essentially modern without developing anachronistically modern mindsets.

So as a historical romance, The Triumph of Deborah is beautifully done. But as a biblical reimagining, for me personally this book fell flat. I have no problem—well, little problem—with exchanging the sexless* biblical Judge with a fully female Deborah confronting societal prejudice and her own sexuality, but I was disappointed to find the powerful, rational woman of my imagination replaced with a woman defined—and confined—by her gender.

The Triumph of Deborah is the third of Eva Etzioni-Halevy’s novels about biblical women. For more information on the author and her novels, visit her website.

The Triumph of Deborah by Eva Etzioni-Halevy. Published by Plume, an imprint of Penguin. Purchase at Barnes & Noble, Amazon, or a bookstore near you.

Thank you to the author for graciously providing a review copy.

*For a figure in Judges 4 whose gender does matter, I would offer the example of Jael. As Sisera is destined to be “sold into the hand of a woman,” it is vital that Jael’s lethal tent spike is wielded by a female. In the Bible, Jael is hailed as “most blessed of women” for her heroism, while Barak in The Triumph of Deborah sees it as an act of feminine treachery. Like Deborah accepting that “men have the wisdom of the mind, but women have the wisdom of the heart,” there is something about the condemnation of feminine physical heroism that seems, to me, to counter Etzioni-Halevy’s message of sexual equality.

Interested in winning a copy of The Triumph of Deborah? Check out Lacuna's first issue Review Contest!

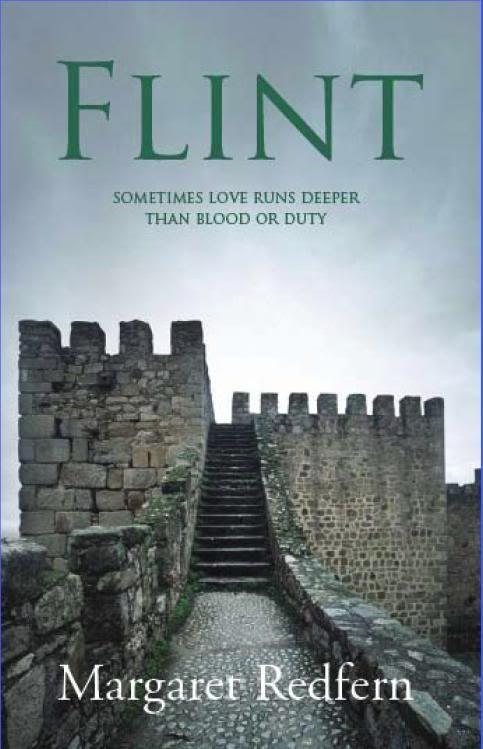

Flint by Margaret Redfern ★★★★★

“Two months after they showed off the Welsh prince's head through the streets of London, my brother Ned sent me a token that told me I'd never see him again.”

In the late thirteenth century, Edward I of England built a series of castles throughout North Wales; the first, and one of the most unusual, is Flint. Margaret Redfern's first novel has much in common with its eponymous setting: unique, mysterious, solidly beautiful and lingering long after the first glance.

Flint tells the story of two English brothers, Ned, an enigmatic mysterious mute, and his younger brother Will, the book's endearing and very human narrator. The boys are sent from their home in Fens to north-eastern Wales, where they are to join the ditch-diggers preparing the foundations for Flint Castle. Ned's past association and lingering fascination with the exiled Welsh bard Ieuan ap y Gof puts both brothers in danger, forcing them to face the truth of their relationship and their own identities.

It is difficult to summarize this novel past the first dozen pages: Flint is full of twists and surprises—"As many as the carvings of the old crosses," as Will would say—and all of them should be savored in the book itself. And I do mean savored. Redfern's plot is rich, detailed, complex, and so are her characters, from the Fenland Peter Long—

"Long words and long winded, that was Peter. Long everything, so he said. Small wonder we called him Peter Long. He liked it. Called it his creed. He'd a broad smirk when he said that, broader still when some called him Godless."

—to the noble Lady Angharad:

"She was beautiful. Every storyteller knows that. We all know how ot describe how her hair is loose about her shoulders and black as the raven or gold as the risen sun or her lips like a thread of scarlet…This woman? How could I say? I was only a boy but I remember her as beautiful with a beauty that comes from the soul."

There are novels you read for the sake of the plot or characters, forgiving frequent lapses in style—Flint is not one of them. In addition to being able to spin a good yarn, Margaret Redfern can write. Will makes an observant, distinctive narrator, and Redfern's excellent sense of understatement keeps the emotion sharp. The chapters open with beautiful pieces that may best be described as prose poems, such as this from chapter one:

"Huddle into yourself. Heft the blanket round you. Ice cracks in its folds, settles into silence. Frost ghosts the marsh grass. Nightjars are noiseless. Dark rises up from the land .It swallows the sky. No moon: it is neap tide .The sea is hussing behind the sea bank, safe, caged. Wind shivers hard reeds. They rattle like bones. Far off, a screec howl on the hunt. Black pools glitter with stars. The real stars are high above. They are singing inaudibly, endlessly, in the cosmos that stretches to infinity over the flat fens. Tonight, if you listen hard. Tonight, if you are patient. Huddle inside your whitening shroud. Settle yourself to wait."

Flint is a novel you can read for the sheer joy of reading—and that is the highest praise I can give to any writer.

Flint by Margaret Redfern. Published by Honno Press, dedicated to publishing the work of Welsh women. Purchase from the publisher , Amazon, or a bookstore near you.

Interested in winning a copy of Flint? Check out Lacuna's first issue Review Contest!

0 comments:

Post a Comment