Where is Gertrude Bell?

by Kyle Hemmings

She wishes to see her aging father. The foreign secretary’s words tumble in Shockley’s mind in all their nefarious connotations. Is she dying or is her father? Was it a ploy to get him to agree to this mission of locating Gertie in Baghdad? Is the press putting so much pressure on government officials to retrieve her that lies, even small white lies, must be invented? She wishes to see her aging father. Perhaps, Dr. Shockley thinks, sitting in a London office cluttered with plaques, war memorabilia, maps, columns of papers, some stamped “confidential,” there might some truth to it.

He puffs on a fat stub of cigar, and lets out a lingering island of smoke. He glances straight ahead, to the window overlooking the mist hovering above Trafalgar Square, then to the right wall, the commissioned portraits of Cornwall, Disraeli, Lloyd George. Lloyd George looks rather stiff in his penguin tails.

Sir Percy Cox hangs up the telephone and says, “You’d think with the hush hush nature of this there’d be less paperwork. I’m drowning in it.”

Shockley offers his best Sunday-garden variety smile.

“Bureaucracy is the eighth wonder of the world.”

Sir Percy, rubbing a tuft of white hair, stands, then paces behind his desk. He lifts a lifeless file of papers and throws them across the desk. They fall, lie pell-mell on the carpet. He motions Shockley not to pick them up. “No, no,” he says, “they’re all rubbish. Bureaucratic nonsense. They really don‘t have a sense of priorities upstairs.”

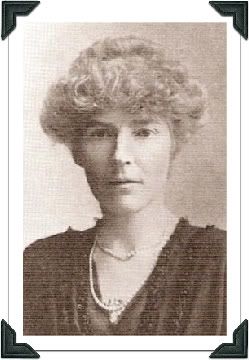

What’s really important, he says, hands clasped behind back, walking towards Disraeli’s portrait, is her welfare. This woman, he goes on, who had supplied us with so much useful intelligence during the war, is now lying sick in Baghdad with a bloody walking pneumonia. Granted, she was brilliant. Granted, she was a little, how shall we say--misguided? But the desert, Sir Percy Cox is telling him, is not a fitting place for an Englishwoman to live or die in.

Dr. Shockley sits tapping two fingers on his knee, watching Sir Percy look up at Benjamin Disraeli pointing to a map of Egypt.

“Do you agree, Doctor?”

“Absolutely, sir.”

Sir Percy swings his shoulders around. Shockley tries to picture what Cox looked like when he had hair.

“On behalf of the Prime Minister, we are so lucky that you agreed to this. Not only a medical doctor. But someone who grew up with her. You’re a gift from God.”

“Wouldn’t say that, sir.”

“Some tea, Doctor?”

Shockley declines.

Yes, yes, Percy goes on, striding towards the desk, he sent visitors up to see her, but she refuses reception to all but Faisal. Sir Percy stands blinking over to the far wall as if he lost all train of thought. Then, he goes on about her father’s recent illness. “Oh no, no, nothing of a serious nature, could be used as leverage to persuade her to return.”

Shockley pulls out a timepiece from his vest. He looks up, studies the Foreign Secretary who’s frozen is some sort of trance. He clasps the timepiece and tucks it back in.

“She must be dreadfully pale,” says the doctor, “ I mean with their kind of medical attention.”

“Imagine so. And this situation with the Arabs. They think she’s one of their own. Fancy that? You know, her bit with the war and all. Won’t say it will be easy. But Faisal gave us his word he’d allow our entry.”

Sir Percy holds up another stack of files. He cites the recent murder of British soldiers in the outer provinces. He cites the fact that civilian sea voyages to Persian ports have been temporarily suspended. After flattening a map against the desk, he raps a ruler against it. Shockley rises from the armchair and joins him. He muses over red serpentine ink lines running over Mesopotamia and the Mideast.

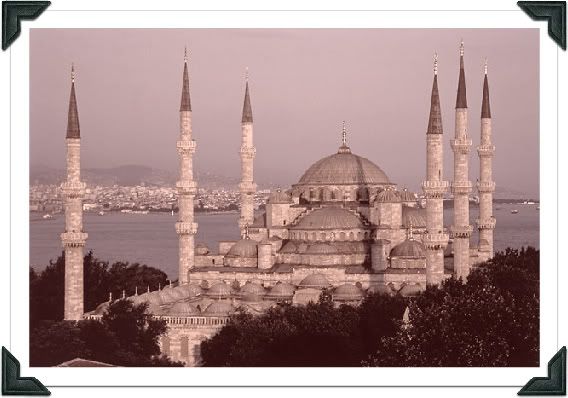

Cox suggests a more roundabout journey starting in Istanbul, recruiting the aid of two others well acquainted with the desert. Whatever way, he tells Shockley, danger is imminent. So vigilance, Doctor, vigilance is your best friend.

Not to mention, he adds, we’re running out of time.

“You mean the pneumonia?”

“I mean a deadline, Doctor. The press is on my back day and night. They want answers. The people want her home. They see her as the last rays of a setting sun. And our communication with Faisal‘s people leaves much to be desired. I wish to wash my hands of this affair as soon as possible. I‘m sorry. I didn‘t mean it like that.”

“How did you mean it, sir?’

“I mean her sick father wishes to see her. That is what you shall tell her. Lay it on thick. Bring her back. That is all.”

Leaning over the rail of the steamship Dory Queen, Shockley looks back at the clouded silhouettes of buildings and says goodbye to England and all those fine droplets, the rest of the world being so terribly dry. England is now a shrinking island, he thinks, standing at the iron rail over stern, and so terribly misunderstood.

* * *

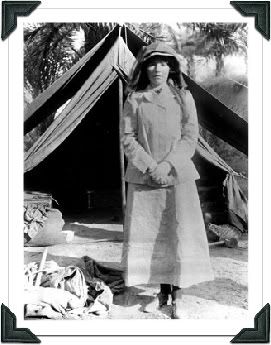

On the ship, Shockley locks himself in his cabin, although the Mediterranean is peaceful as a sonata. Sliding off an oval grainy table is Miss Bell’s book, The Desert and the Sown, a travel book ranked in importance with Dougherty’s Arabia Deserta. He stoops to retrieve it; he pictures her standing in long ruffled dress, saying, “Jolly good job, Stephen, I see you’ve near mastered my whole bloody book. Not too terribly boring, was it?”

Oh, what shall he say upon seeing her? It’s been a long time, Gertie, butterflies jumping off his tongue. He hasn’t faired badly, you know. A mediocre practice, a steady income, paid off some gambling debts, a lonely widower now-- his wife? Oh, the French midwife he met after the battle of the Somme? Her Austrian lover shot her twice after discovering she was married. Shockley delivered an overdose of morphine after she begged him to put her out of her misery, and him out of his. He was cleared of charges and ostracized from the medical community. But no, he hasn’t faired badly.

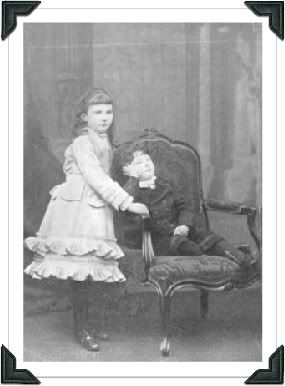

He lies back on his bunk and peruses government sequestered photos of Miss Bell at various stages. In one, she wears a wide brim hat encircled with roses, cannot be more than twenty, he recalls, smiling next to him and her father on Commencement Day, the first woman to graduate Oxford. In a moment of abandon, she allows him a public kiss on the lips.

He stands to shut the small window in the cabin, the salt air is burning his eyes, not to mention the sun reflecting off the water in blinding sparks of light. A weight in his stomach, he vomits half the morning’s breakfast out the window. Better? Yes. Hardly the constitution of a salty dog. He sits. More photos. She is perched resolutely atop a camel with her creased skirt, high riding boots and a kafeeyeh , sitting in the middle of several military chiefs, political advisors -- Winston Churchill, T. E. Lawrence, among them.

Back in England. She drapes one arm over the wife of a Northumbrian iron worker in her overcrowded flat behind a row of her sooty-faced children. Persia. Seated next to a table of unglazed clay pottery, earthen jugs and bowls. Her face is covered in a dark veil, only the slightest hint of her green-blue eyes, which appear here as black and fierce. Standing behind her is King Faisal. Shockley wonders as to the truth of those rumors circulating that he is her lover.

He shuffles and reshuffles the photos.

Which is the real Gertrude? A question, he wonders, one might toss to the wind.

Begging the question. Beg your pardon.

He throws down the photos.

It is a scene he keeps replaying in his head. She is running across flower beds and sunflowers, bright roses and yellowish acacia, chased by her nanny, Mrs. Ogle. He is crying because Gertrude called him a sissy. She crawls across the glass top of a greenhouse, beckoning him to follow her. He hides behind Mrs. Ogle’s several layers of fluffy petticoats.

She falls through glass.

Mrs. Ogle screams.

Lying next to broken flower pots, she waves Mrs. Ogle away. “No. No. You mustn’t help me. I can’t move my leg. But you mustn’t help me. See? No tears, Mummy. I shall stand up on my own.”

Steven stares at the sight of her. He feels like some paltry useless thing, perhaps a jagged piece of those broken flower pots.

Several nights later, he is invited to the Bells’ mansion for dinner. He sits next to Gertrude, who hides her cast under the table. He whispers to her, “Doesn‘t that leg hurt?”

“Stephen, have you ever heard of the word Laban? It’s some sort of delicacy, I believe. I’m not very sure. Someday, I shall taste it in a room of white turbans. All those somedays, you know, they will all add up to one day. The leg? Yes, it does sometimes. Laban, Stephen, I even love the sound of that word.”

He pats his lips with an embroidered white napkin, returns it to his lap. “ If you don’t mind, I much prefer my beef and mutton. At least I know what I’m eating. No, I haven‘t the slightest clue what the word means.”

She taps her spoon on a saucer as Stephen watches her thrust out her chin. Mrs. Ogle turns and grimaces.

“Mrs. Ogle? Stephen would like some more pudding.”

Shockley lies back on his bunk, crossing his legs. He thinks of Miss Bell’s flamboyant hat of flowers in that one photo. Flowers. His mind is floating towards them. Is it possible that there are flowers that can only grow in the desert? He recalls that odd belief of hers that flowers are a very special language and how she would often pick a nosegay of flowers from the garden for her father. This language of flowers, he thinks, it must be as cryptic as the maps of hidden railways she would later draw for British officers. This image of a flower in the desert, he ruminates. So solitary. So damn solitary.

He hunches forward. A doubt leeches to his emancipated gut: how will he survive the desert with his “pudding-like” constitution? And those chest pains visiting him more regularly like a mother-in-law. He chuckles. Rubs a sore gum. Wouldn’t bet a sterling wager for survival. Perhaps Cox will send a search party for Gertrude and him. Ha-Ha-Ha. Yes. Yes. It’s not funny, he thinks, tossing, catching Miss Bell‘s travel book in the air, but it is. Save death for tomorrow.

For now, all he can think of is Gertrude—Gertrude—why they’re both two peas in an

empty pod, aren’t they?

* * *

The rendezvous in Istanbul. Klundt is a large jocular man with a big belly, helped no doubt by his professed indulgences in beer and blood sausages. He sits on a sofa entertaining Shockley with stories of his life as a liaison officer to the Turks during the war. His belly shakes as he tells Shockley how he surrendered himself to the British at Jeddah, wearing only underwear.

“By profession, I import diamonds. By hobby, I’m an archaeologist. By nature, I am a mercenary,” he says, referring to the half-sum of money paid him by the Crown. “It was wise of Cox to pick me. Before the war, I was involved in the excavation of Babylon and Ja! Ja! the fortress of Ukhaidir. And the Royal Tombs. Ach! Beautiful. Inspiring. I have published work on it but it was stolen and taken as credit by others.”

Shockley, smoking a cigar, does not believe the latter.

Fattuah, Miss Bell’s loyal guide in the desert, enters the living room from the squalid kitchen, holding a tray of cooked eggs, tongues and fish. He sets it down and pours the other two wine from a goblet. Shockley studies his features. He does not resemble the man in the government photos, cheerful and plump. In striped faded shirt and baggy pants, he has aged terribly. After serving the two, Fattuah prays facing the window. He eats alone.

Klundt balks at how Fattuah hardly talks, even when spoken to. It’s a suspicious trait, he comments, this raging efficiency. Shockley, putting a finger to his lips, leans over towards Klundt, “He admitted to me this morning that his wife and children were abducted during the war. He showed me their photos. I believe he carries them everywhere. He must be terribly desolate.”

“Nien, I don‘t care if he hears me,” says Klundt, pushing the same finger to his lips. “I will never understand their mentality. I have scars on both arms, courtesy of the Beni Shakir, to show what their mentality amounts to.” Klundt stands up, excuses himself and heads toward a room with chipped tiles, and leaky toilet, a tawdry approximation, Shockley believes, of a bathroom. He keeps the door only partially closed.

After dinner. Fattuah arranges belongings, bags, folded-up tents and mosquito nets. He sits down in a straw chair and smokes a water pipe. His body is small and sinewy. In the dining room, Klundt is absorbed polishing his diamonds.

Shockley spots a thin watchband on Fattuah’s wrist that strikes him as odd. It becomes more conspicuous when Fattuah rolls up his cuffs.

“May I see your watch, please . . . A woman’s watch? You don’t mind me asking, do you?”

Fattuah stands. He raises and flexes his wrist.

“No, Effendum, I do not mind. Miss Bell gave me this watch on a trip to Damascus. It no longer works but I keep it in memory of her. For the reason of . . . Sentiment. Yes. If I need the time, I have ten thousand others.”

Shockley smiles politely, makes no guess as to what he meant by that statement, and slinks back on the sofa. Fattuah remains standing in front of him, as if waiting to be dismissed.

“Effendum. Perhaps this is a good a time as any to give you something. Something from Miss Bell.”

“ Miss Bell?”

Fattuah walks over to a corner of the room and opens up a bag. He holds out a thick box, wrapped in canvas, in both hands.

“Miss Bell mentioned your name on several occasions. She always spoke of you in the highest regard. It is her diaries. One of Faisal‘s guards discovered them and gave to me. I promised I would deliver them to one of Miss Bell‘s trusted countrymen to take home to her family.”

Shockley stares at the leather bag. He runs his hand along the rough canvas cover, does not open it. It weighs like a melon.

“Her diaries? Why weren’t they returned to Miss Bell?”

Fattuah lowers his head slightly and looks at his feet.

“Faisal might have destroyed them. A diary could contain information causing animosity on both sides. And there is much looting in Baghdad. It could fall into the wrong hands.”

He raises his eyes to meet Shockley’s.

“An extraordinary woman she was. A chief of the Anazeh tribe once said if you add so many men, so many men, they would not add up to one such woman.”

An amazing thing to admit, thinks Shockley.

Fattuah carries trays of half-eaten plates to the kitchen and begins scraping them. The screeching sound makes Klundt jump. “Must you make so much nooooise,” he yells.

Shockley throws cold water on his face, changes his clothes, then goes for a walk along the narrow streets and mated small houses. The sun is low and yellow-gold. He wants to clear his head of all of this. The diaries. What was in them? When will Cox’s telegram of further instructions arrive? Can he trust Klundt? And this whole situation with Bell that if mishandled could prove a diplomatic disaster.

The sun washes the dome of Hagia Sophia with orange-red rays. He closes his eyes, attempts faltering half-steps like a blind man. He pictures Gertrude. She’s traveling on a donkey through a busy bazaar like the one before him on her way to visit the Sultan. He read it in the transcripts. She returns to England to support women’s suffrage and to help the impoverished wives and mothers of iron and steel workers. She collapses in a chair under a portrait of Queen Victoria.

Where are you? he thinks. Have you aged poorly? Are there now lines on your face? Must get you out of bed. I’m coming to take you home. You have traveled too far and have stayed too long. You are in blackest of mood. I have a sense of this.

Shockley opens his eyes. He returns to the apartment. Klundt hands him a telegram from the London Office. “It just arrived,” he says, with a half face of shaving cream.

The office, it states, has received Shockley’s telegram of his arrival and is most sensitive of the situation. They are to be cautious. Violent confrontations everywhere between tribes. No mention of a military escort. Faisal reneged on his promise to provide one of his. Cox cannot be reached. Further efforts will be made to contact Lord Burke’s Office in Inshafan. Miss Bell refuses to receive members of the British press. No word about her condition.

Shockley crumples the paper and tosses it to the floor. We’re leaving tomorrow, he announces to the other two. Klundt yells from the bathroom that he has nicked his face with a razor. Fattuah says nothing. Shockley is tempted to open the diaries but doesn’t.

The Nejd. The sun is a treacherous flame over an immense oven. Shockley’s head pounds and his cheek bones burn like tiny charcoals. He’d prefer quicksand or a quick death. Granules swirl and lodge themselves in his eyes and make them sting. He sees this endless void of sand, nothing but sand and his head hums. He wonders. Is it his own voice that is speaking over the hum?

Before them, the carcass of a dead goat. A man in white turban sits next to it and waves to them. They are now miles from the jeweled mountains of Druze country or the stalking fields of the Hauran plain.

Shockley swings around. A familiar sound makes him wince. The last of the three mules brays and drops to the ground. Klundt curses the animal and instructs Fattuah to bury more luggage; it will only weigh them down, he says. The two sit still in the furnace. “Done,” says Fattuah, wiping his hands of sand. They press on.

Klundt points out ancient relics and ruins they pass, pieces of china left in the desert, he calls them. Shockley replies that they should not have discarded so much luggage, that there won’t be enough blankets at night. He’s always shivering. “Nonsense,“ says Klundt abruptly, raspy, “you are too thin skinned.”

The monotony of the camel‘s steps is numbing Shockley’s brain like a lullaby.

“Effendum,” says Fattuah from behind, “do not stare into the sun.”

But he does.

The sun looms larger and threatens to engulf him. He wonders if they are traveling upside down on its surface and the sand is really sky. It is all he can see and all he can dream of, but he can never think in this confounded sun.

Wonder. Wonder. Wonder.

What would a man hear, he wonders, if his puts his ear to the desert floor?

A clock ticking?

Wind chimes?

Voices of slain soldiers?

Nothing?

His own thoughts?

He ponders this. What time is it in Cairo? What time is it in Oxford? The time it takes him to get to Baghdad. How much time, he muses, do they really have? Here, there is no time. Time is endless or one spasm of it. What time is it? Will they reach her in time?

All those discussions about time back at Cambridge: Plato, Hegel, Bradley, Aristotle, Schoepenhauer. Whose time was correct? Whose time is it? Tell me, thinks Shockley,

how do you tell the time here? Without a watch, he is lost. Ask Fattuah, he thinks. He has ten thousand watches all ticking at a different time.

In the desert, thinks Shockley, there is no time.

His head rocks back and forth and the voice inside his head grows persistent, grating. He looks ahead and watches Klundt‘s body gently sway on his camel as if dangling from invisible rope. He wipes his eyes. Klundt’s figure is still a wavering outline in water.

The sun, thinks Shockley.

The Sun. The Sun. His Royal Majesty, the Sun. His Holy Eminence, the Sun. Now that, he knows, was always an instrument of time. What clue does it give in finding Gertrude Bell? Where is Gertrude Bell with her long reddish hair and freckles, that bright bouncy girl he once played with?

Conjure this image of her. She is running past all clocks and meadows and rose gardens. She is the same Gertrude he remembers burying her pet next to her real mother, the same Gertrude who once fell through glass, the same Gertrude lying with fever in Baghdad.

He suspects Miss Bell is somewhere destroying all maps, smashing all clocks.

Entertaining thought. Miss Bell lives in the center of the Sun which is a useless measure of time because it is a hollow sphere which is at the center of everything he desires and no moment precedes or succeeds any other . In the sun, he can only travel in circles.

His conclusion: They are headed towards the Sun and not Baghdad.

He watches Klundt drain the last drops of water into his mouth. Klundt’s voice bellows in the air. “I am turning back! Our water, supplies, are too stretched.”

“Nobody is turning back!”

He now accuses Klundt of leading them far off course. He says he believes Klundt has deceived them into an unspecified route so he can visit more excavation sites. Klundt shrugs and laughs as if teased by a coquettish belly dancer. Shockley, speaking to the back of Klundt’s head, claims that if the sun had not drained him of strength, he would hold him at gunpoint and kill him.

“But you have not the nerve, English! The heat has soaked up your reserves.” Klundt reverses the camel‘s direction.

“You were paid to take us to Baghdad! Turn around.”

“I never promised to take you to Baghdad. I promised I would lead you to the safest route. Tell your English matriarch Klundt says Guten Tag .”

“You bloody call this safe? Leaving us to die in the middle of nowhere? Stop!”

“Doktor. Who do you think you are looking for? A woman with the title of archaeologist and the soul of a street urchin. She is a traitor to your beloved Crown and not even Faisal has any use for her. She will sell herself to the highest bidder. Do you know what I know? Are we three blind mice? One blinder than the other? This woman must have harbored delusions of ruling Persia alongside Faisal. The king was inspecting his troops. She galloped at full speed to be at his side. He turned his head and ignored her. Ach! He dismissed her without a word. Ja! Just like that”

He snaps his fingers.

“And something else you should know!”

“ I don’t want to hear it! You’re speaking bloody rubbish! How do you know this?”

“I have my sources in Baghdad. Ja, She helped him get elected. But now she is worthless as a used rag to him. The price of love. Go. Break your heart looking for her. As for me, I will break my heart looking for water.”

“I’m warning you. Turn around.”

“Break your heart.”

Now several feet behind their camels, Klundt is whistling what Shockley believes is a German beer hall tune.

As if not with his own hand, Shockley reaches for his revolver and . . .

“No!” screams Fattuah.

Fires.

Klundt falls from his camel with a sound the dying mules made when hitting sand.

The sun, thinks Shockley.

The two stand over the body, neither one speaking. Shockley throws down the gun. He mumbles to Fattuah without looking at him.

“I did not do that. I did not kill him. My God. ”

“We will bury him and say nothing,” says Fattuah, kneeling, scraping back an area of sand, his knees darkened in blood. “In the desert, you sometimes step outside yourself. You sometimes become a different person who does things you would not ordinarily do.”

They drag the body into a dune, cover it with sand. He never trusted him, says Shockley. It wasn’t the route they agreed upon. Unspecified. Unspecified.

Yes, says Fattuah. Say nothing. They must reach Baghdad.

Shockley remounts his camel and falls. Fattuah cradles his head and pours water over his face. Shockley struggles to sit up, Fattuah‘s face has eclipsed the sun.

“Are you alright, Effendum? Cannot give you more water. Not enough.”

“Where are we?”

“ Do not know.”

“I didn’t kill him.”

“No, you did not.”

“Fattuah . . . What time is it?”

That night in a tent, shivering, Shockley takes out Gertrude’s diaries, rips apart the cover and turns to the few blank pages towards the end. His head still humming, and his body so weak, the sensation of falling down a dry water well, he writes in shaky script. The image of the Sun still swells in his head.

I am standing in the drool of the afternoon and in the far corner of her room. Our fingers work like squirrels, inept squirrels, no time for self-loathing. Shall I taunt her with my strapping figure? Or shall I fool myself in complete disregard of mirrors?

Off with those boots! Off with those buttons! Off with those starched smiles. We fall onto a spongy mattress and kick off the top layer of sheets. She is bleeding sand.

She is somewhat bigger boned than most of the women I have known. But I suspect she is in some way more brittle than they.

Outside our dusty room, soldiers click their boots towards Damascus. But here, all afternoon, we, children playing with sabers, imitating soldiers, grow so derelict of our righteous agendas.

Facing the ceiling fan, I pose to her my ultimatum: Will it be Faisal or me?

She leans into my arm, gazes down at her hat of flowers on the floor.

“You pompous bastard. You forgot to shut the blinds.”

She laughs.

I turn away from her.

She slips a hand over my shoulder. Why so sad? She asks.

“Our timetables,” I say. “With you, I feel lighter than air. When you leave, the air is stones.”

She leans her head against the back of my shoulder and taps a finger in perfect rhythm.

“I know. I know,” she says. “Whenever I’m feeling wretched, I think of the beauty of tamerisk trees. Their calmness. Their ability to sway but stay resolute. It helps get me through the day. Helps keep me chipper.”

There is a knock on the door. Hush! I jump to the floor.

It is Fattuah. Dinner, he announces, will be served in ten minutes.

* * *

Faisal’s camp outside Baghdad. Shockley dismounts and approaches a king’s guard. He hands over papers requesting reception with Faisal. The guard, barely looking at it, instructs him to wait. He returns, tells Shockley he can go in but the other must wait outside.

Shockley enters a large tent and addresses Faisal, who looks thin and solemn and faces away from Shockley.

“Your Majesty, I am very grateful you have allowed me an audience. I am sure you have been expecting my visit.”

Faisal, looking distracted, slowly turns and half smiles. “And how can I be of service to you, sir?”

“Your Majesty, you must excuse my appearance; we have come a long way. I am asking permission to see Miss Bell. I understand you have granted permission through our ambassador. The London Office wishes to inquire into her state of health as quickly as possible. I ask your assistance in seeing her.”

Faisal rubs a thumb along his jaw and stares curiously at Shockley.

“Miss Bell? You have come for Miss Bell?”

“Yes, your Majesty.”

“My dear poor man. How long have you been traveling in the sun? It can be rather strong. I’m afraid Miss Bell is no longer here. Miss Bell is dead. I never believed it myself at first. A woman of Miss Bell’s stature succumbing to pneumonia. Our doctors did what they could. She had done much for our liberation. I might add, uhm, she was given a most impressive military funeral. What route did you come by? . . . I will provide adequate lodging and food for you. And, of course, arrange a safe transportation back home.”

“Your Majesty, I have documents from Sir Percy Cox. She cannot be dead. And I received a telegram dated May 3, 1926 still confirming our mission. It cannot be more than two weeks old.“

Shockley’s fingers fumble through the pockets of his dirty khakis. The telegram, he now realizes, was discarded. Faisal waves his hand, tells him to search no further.

“Sir, my humble apologies. But I believe today’s date according to your calendar is now June 27, 1926. Yes. The sun can do that. Make you forget time. And as for your Sir Percy. Again, my good man, what route did you come by? It is my understanding that he resigned from the Office recently.”

Shockley is stone faced and unblinking. His words tumble out in the hush tone of a dying man.

“We came a very long route.”

“If it is any consolation, we Arabs had a saying about Miss Bell. That so many men, so many men, could not equal one such woman.”

“An Englishwoman must never be afraid.”

“Yes. That was a favorite motto of hers. So few of us are destined to achieve immortality.”

Shockley stands numb, studies the trimmed hairs of Faisal’s beard, feels dizzy. He bows and excuses himself.

Outside the tent, he finds Fattuah, sitting on the ground, knees drawn to chest, pitching stones. His face is blank, listless, gazing off into the distance. He calls out to him, there is no response; he cannot stimulate even a twitch.

“You knew, didn’t you? You were her closest . . . Perhaps you found her dead. Perhaps you took her diaries. Perhaps . . . Perhaps. Why didn’t you . . .”

“I have done a dishonorable thing, Effendum. I agreed to accompany you for the money. It will cost me to locate my family and I cannot believe they are dead. It would have been unwise to say the truth.”

He rises and faces the orange flame of sun, setting.

“I do not believe she died, Effendum, not a woman like her. Forgive me. I had read through her diaries. A terrible thing to do, yes, I admit. Each day, I hear her voice from those pages. But you can still find her. If you just open the diary and follow her voice . . .And now, I must find my family.”

Fattuah wipes sand from his red pants and wanders away toward the open desert. He walks until nothing but a speck in Shockley’s line of vision, a dark granule fading into a blur.

Yes, Shockley thinks. The watch Miss Bell had given him had stopped. It does not matter now. She is beyond all timetables, beyond all deadlines.

His brain cries out for water.

Klundt is dead. Gertrude is dead. Fattuah will die starving mad. And this he thinks is what he has to show for his labor? A handful of sand? His marvelous new theory—he lives in a world staged with stupid bloody puppets of which he is one. At least if he could bleed oil, he‘d be rich!

He looks around. The desert is spinning.

Recedes.

Enlarges.

An ancient sponge throbbing.

He is standing upside down.

Klundt was right. Break your heart.

He collapses.

He awakes on a dusty blanket, glancing upward towards the dome of a billowing tent. Sand granules lodge on his tongue, grate against his teeth. A veiled woman wrings water from a towel and pats a cool one to his forehead. Shockley pushes her hand away, slowly rises, grabs Gertrude’s diaries from a saddle bag. He frantically flips through the pages. He settles on Gertrude’s last entry.

“. . . Sir Percy left not more than an hour ago. He was pacing and pacing and I was smoking up a storm. I dare say his pacing was driving me over the edge. ‘How could he?’ I screamed. ‘How could Faisal reject the mandate! Stab us in the backs so?’ Oh, did Sir Percy explode. ‘I told them. I told them. Leave this whole bloody Mesopotamian Affair to the India Office. Let them handle the rule. Gertrude, go home. Go home. Your work here is done. Both sides have much to thank you for.’ He stomped out of the room, gripping that riding stick like a weapon. That dreadful ceiling fan spinning ever so slowly.

“I ran to the stairwell, catching myself on the rail, coughing my silly head off. Don’t leave me! Don’t leave me alone! You’re the only damn friend here I have left.

“Was I crying? Mustn’t think so.

“Undressed. Threw on a robe. I tried to nap. Really I did. It was useless. I awoke. Imagined Faisal standing over me with that sly smile of his, ordering me to strip.

“ . . . I am coming down with chills; my head feels like a heat blister. I look out the window. Could acacia grow in such a non-indigenous climate? It’s funny what an illness can do to one. And didn’t mother die of pneumonia? How I wish father was here; he must be getting too old to take care of those flowers back home.

“I stagger to the bathroom, my chest heaving, hurting, smash all these mirrors, this face, it cannot be mine, so lined, so haggard, and I am growing smaller; I am running through the rooms of my parents’ mansion in my velvet dress and blue stockings, a knock at the door—ah! Stephen back from the Boar war—how handsome he looks in uniform, you love me or not, he asks; put me on the spot, I say, you know my head is as smoky as a room of narghyle , and sitting so poised on the sofa is this stranger in white robes, asking my father for my hand; I cannot see his face and no, the suitors are sitting all neatly in a row and I say to him, ‘Oh, Papa, they are such nice and handsome young men, but they are oh so terribly boring;’ and I am riding to greet Faisal, amidst ten thousand rifles raised, My Love, we shall rule Persia, you and I—and he shunned me, shunned me, shunned me—and I am growing smaller, descending into crowded basement rooms, the stench of sickly flesh, the flesh of interrogated prisoners, of Moslem girls who will die giving birth, everywhere sooty-faced children and the corpses of their brothers; and they’re telling me to go home, Gertrude, your job here is done, go home, and water your English garden and tend to your English flowers, that is what a woman does, isn’t it? and my chest is squeezing; I need fresh air, fresh air; I open the window in my parents mansion; I open my window in Constantinople; I open the cabinet door -- there are small bottles, unlabeled bottles, dark tinted bottles, curious bottles, outdated bottles, tinctures, extracts, elixirs, alcohols, salves, ointments, sleeping pills.

“Sleeping pills.

“Sleeping pills?

“Pills that make you sleep.

“Papa, where are you! Have I grown too small, too old, too weak to live?

“Oh dear. What a silly woman I am. A middle aged school girl stuck in the middle of all this. Perhaps, Sir Percy, you look down your nose at me too. Just like all your fine officers and their stuffy wives. All along you were just pretending to protect me from all those men who thought me their inferior. In the end, politics prevails and I am sand and dust.

“An Englishwoman must never be afraid.”

Gripping the diary, Shockley parts the flaps of the tent and stumbles into open air. He rips out pages, one after the other, crumpling them, pitching them into the breeze. He watches the balls of paper scatter in the sand, hopes they will blow away as far as the Euphrates, perhaps further, across the English Channel. He throws down the shredded book.

A curly-haired child begins poking a twig through several of the papers, making a game of it. He runs over to Shockley, motioning him to retrieve a page off the bark. He stands smiling before him as if expecting a reward in dinar . Shockley thanks him, lifts the topmost paper. After turning it upside down, over and back, he holds it steady in the dying light. The perforated paper is almost unreadable.

My poor precious men, what has taken you oh so very long? You must have walked for an eternity. Come out, come out from under that wretched sun. Do come in and help yourself to some fresh orange water and biscuits. It is so dreadfully hot, isn’t it? Will you be staying for tea? Please keep me company.

The woman standing before him, in long ruffled dress, twirling a parasol over her wide-brim hat of flowers, walks away. In the distance, she becomes something small, wispy—gone by sundown.

Of course, he realized. It was not what the paper had read. There was no woman before him. He had put his ear to the desert floor. He heard a shadow falling through glass.

Rather a fine madness.

Kyle Hemmings lives and works in New Jersey. He has work pubbed in Noo Journal, Riverbabble, Elimae, Apple Valley Review, and others.

What is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

I think the most important part of a historical fiction story is character. No matter who you are writing about, or what facts you choose to include or ignore, the character, as in all good fiction, must stand out and be fascinating.

0 comments:

Post a Comment