The Pretender

by Kenneth Radu

Stepping off the train in Berlin’s Zoologischer Garten station, Olga shuddered. Since her family’s exile, she had developed a distaste to the point of disgust for Germany. The havoc it had wreaked during the war years on her poor country, the shameful treaty it had engineered with the Bolsheviks to Russia’s great disadvantage, and Willy the Kaiser who had betrayed all family connections and feelings—she would have preferred to avoid Germany at all costs, not to speak the language. But God in the end dealt with an even hand, for despite all his puffing and strutting like a wind-up toy soldier, Willy had also been deposed—although not executed, like her own brother. Careful, Olga, however tempting under the dreary Berlin sky this March day, revenge was an emotion best avoided.

At least she had worn her favourite “good” dress of grey wool with its vertically pleated bodice and circular white collar, and a single strand of pearls, a gift from her father. With hair in braids neatly arranged on her head, feet in sturdy English brogues and a thick sweater under her coat, all effective outside the station where she hunched against the chilly bluster of the German winds, Olga looked like a country hausfrau come to town for a doctor’s appointment. Across the road stretched the great zoo, home apparently to the world’s largest collection of imprisoned animals—or was that more German hyperbole? There had been wildlife in Tsarkoe Selo, a more modest kind of zoo established for the entertainment of imperial children. Odd, she hadn’t given those animals any thought at all until this very moment. What would have happened to them during revolution and times of starvation and mass murders?

In German, Olga told the driver to take her to a hotel on Kurfuerstendamm, a boulevard passing through an elegant neighbourhood of Berlin where a woman claiming to be her niece Anastasia waited to meet her Aunt. Waited for official confirmation that she was indeed Anastasia, that she had survived the massacre. Why, oh why, Olga thought in English, the language she resorted to more than Russian or French since her escape from the Crimea, had she allowed herself to travel from Denmark to speak with this woman, so obviously an imposter? Her mother categorically refused to participate in any lunatic’s charade, would have nothing to do with claimants and pretenders, so exasperated by their importunity that she denounced them in French, German and English: ils sont tous les menteurs et les fraudes; sie sin alle Lugner und Schwinde, liars and frauds all. It both infuriated and saddened the Dowager Empress that a few Romanovs on the edges of the family with their hangers-on believed this strange woman who called herself Frau Tchaikovsky was truly the tsar’s youngest daughter.

Paying the driver, Olga looked up to the third floor of the elegant white hotel, surprised that a woman bereft of fortune, if not name, could afford the rates. Of course, people who thought to gain from supporting a pretender’s claim probably paid the bills. Gain what? That mythical Romanov horde of gold and jewels? True, some money remained in a Berlin bank, but raging inflation the last few years had diminished its value to insignificance, hardly worth the effort of machinations and charades. Stories of shoppers pushing wheel barrows full of German marks to the local butcher shop were not far off the mark, Olga recalled. No real fortune existed, just her mother’s box of personal jewels kept under her bed in a Danish villa. The Dowager Empress and her own sister Xenia, the closest surviving kin of the butchered imperial family, would not live on the charity of royal relatives if a great fortune were available.

Bracing herself outside Frau Tchaikovsky’s room, trying to fathom how to greet this woman, what to say, what language to use, Olga reached into her purse for a handkerchief to wipe her nose dripping from the cold. If emotion overwhelmed sense, the wrenching ache of her heart would topple reason and force her to embrace the lost Anastasia simply because, if truth be told, she wished it to be so, to discover her niece alive. She had asked to speak alone with the pretender so as not to be in any way influenced, so the woman herself would not in any way be prodded or reminded of her pre-revolutionary life.

No doubt Olga would hear any number of “facts” to prove the woman was who she said she was. Anastasia had been her favourite. All the four sisters often spent a Sunday in her St. Petersburg home, and Olga knew the intimate details of their cocooned lives in the Alexander palace. Who better to know the truth than Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, sister of the tsar, aunt and confidante of the imperial sisters and that dear sweet boy, the tsetsarevitch Alexei? How they had romped through her St. Petersburg rooms, playing hide and seek, and staying up late at night putting on little plays of their own creation and telling stories. Olga knocked on the door, gently at first, then harder as if to demand entrance.

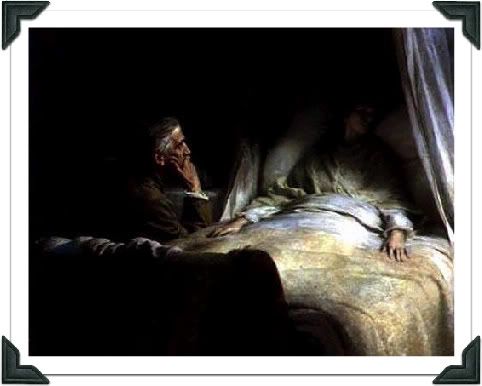

Startled by a short-bearded man in glasses and German worsted suit who opened the door, Olga said nothing but nodded when he introduced himself in Russian as Her Imperial Highness’s personal physician. At first Olga was tempted to say “you can be no such thing,” but little was to be gained by arguing with a retainer. Ah, there she was, sitting up in bed wearing an white eyelet bed jacket, unsmiling, although much of her face remained in shade—for the draperies had been drawn against the hard winter light—and not holding a hand out to greet her aunt. Olga stepped forward, surprised to be so calm as if she were simply piecing together a jigsaw puzzle.

The doctor—perhaps that much could not be disputed, after all—leaned over the bed to check the woman’s pulse. Olga had been told by English relatives that Frau Tchaikovsky had attempted suicide by throwing herself into a river—Paris? Berlin? She had forgotten the exact locale. And of course, whatever injury sustained during the horrid execution of her family continued to have consequences of a severely traumatic nature. Imagine what Anastasia had witnessed. The family’s loyal Doctor Botkin had also been shot to death in the basement.

The problem only existed if Frau Tchaikovsky were in fact Anastasia. Something about the lips, the face, the eye colour, Olga could see a resemblance. But what of that? Many people unrelated by blood resembled one another. If she were allowed to sit on the bed and peruse the face, watch the lips move as the woman spoke, search for the familiar glints in Anastasia’s eyes, but clearly the woman, who raised the blankets to her neck, preferred not to be closely examined.

The son of Dr. Botkin, Nicholas’s personal physician, supported Frau Tchaikovsky’s claim. Olga shrugged off the notion that a strong case could be made simply on a basis of resemblance. How unfriendly the glance; Anastasia had been full of frolic and mischief, pouted occasionally as all children did, but this woman’s unfriendly, forbidding stare visible through the shadows, as if to say how dare you—Anastasia could never have managed such a contemptuous, hateful look as an adult. But perhaps anxiety, perhaps fear, could twist an expression contrary to one’s intention, and for a moment, Olga thought she recognized—oh so fleeting, so vague—how could it be? How dare she what? It had not been her idea to travel to Germany by train and waste her time with a pretender.

Some courtesy, please.

Unless the Frau believed that hauteur and rudeness constituted regal demeanour, a common misconception. The Tsar’s children were taught to be dignified, gracious and humble in public, never presuming upon their station as imperial personages. Avoiding Olga’s perusal by looking down, looking away, not meeting eye to eye, this woman covered her lower face with a hand, pointing to a chair away from the bed for Olga to sit down as the physician constantly bustled between them, checking the woman’s pulse again, examining her eyes, fluffing the pillows, whispering in her ear. The very sound of her voice when she deigned to speak offended.

Olga addressed her in Russian.

“Pardon, madam,” the doctor answered in Russian, “but Her Highness has lost the use of her native tongue.”

“Lost? Whatever do you mean?”

“A blow to the head ... trauma ... affecting that part of the brain where language resides, also her memory.”

“Yes, of course, I understand.” Although Olga retained her doubts, she supposed such an unspeakable and terrifying experience in that dreadful house, such appalling physical injuries, if not mortal, could have resulted in a loss of language and amnesia.

She then asked the woman in French if she was unwell.

“Pardon me, madam,” the doctor spoke, again in Russian, “but Her Highness does not understand French.”

“She has lost that language as well?”

“The trauma, you understand, was severe.”

“Anastasia also spoke English.” Olga reverted to the language she preferred to speak.

“Ah, forgive me, Madame ...”

Then the woman in bed blurted out in German, “What are you talking about, what are you saying about me?”

So taken aback, Olga almost forgot her own German. Anastasia had never learned that language.

“You speak German?”

“After her escape from Yekaterinburg and Russia,” the doctor answered on behalf of his patient, “she spent time in a German hospital, you see.”

“Yes, how unpleasant it must have been for you, Anas....” Olga stopped in German, unable to call the woman "Anastasia."

“What shall I call you?”

“I am her Imperial Highness the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolayevna.”

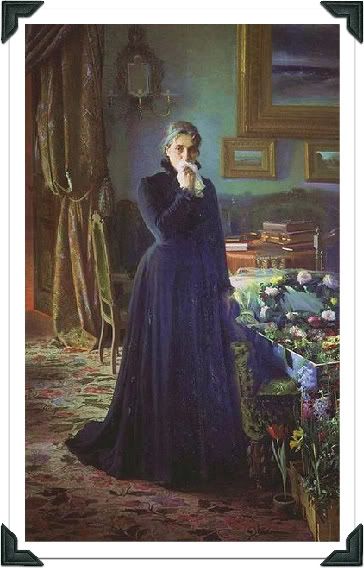

Olga stood up and walked to the third floor window, both shocked and offended by the woman’s presumptive appropriation of her niece’s name and status. The doctor responded to what appeared to be the onset of a mild hysteria as Frau Tchaikovsky grabbed at her neck and shouted in a mixture of German and Polish, two languages Anastasia had never learned. Nor had she begun to talk about her niece’s childhood, about her family life in St. Petersburg, Tsarkoe Selo, Peterhof, of yachting in the Finnish fjords, of summers passed in the Crimean palace of Livadia, to find out what the woman knew. Allowances had to be made for trauma, many allowances it seemed. And yet, despite fighting against her doubts, Olga saw, refused to accept what she thought she had glimpsed in the darkened room, perhaps no more than the play of shadows on a face, that indefinable look, a kind of subcutaneous expression, reminding her of Anastasia when she was upset as a child. If only, if only—Olga removed her handkerchief again to dab her eyes, for she wanted to cry.

The woman in bed kept pushing the doctor’s arm away, refusing to swallow pills he offered, swearing in German, something Anastasia could never have done as a child in any language, so obviously distraught that Olga’s heart and scepticism softened. Clearly the woman had lived through a ghastly experience like many of the surviving Romanovs, a hell on earth. Other family members had died terribly, her poor brother Michael, tsar for a day after Nicky’s abdication, then shot to death in a forest. The tricks of the heart, Olga lamented discreetly by the window, parting the draperies and looking at a row of lime trees in front of the hotel. How cruel these pretenders were, so adept at playing on human pain and yearning, like expert violinists plucking the strings until they responded in tune to their version of the events. In the end, one played along with them like the Frau’s supporters for the sake of believing that the unimaginable had not in fact occurred, that nightmare need not be permanent, for the sake of whatever private fantasy they wished to fulfill.

Coughing first, Frau Tchaikovsky began shouting out childhood events in German, what Anastasia did, what she wore, facts dredged up from a broken memory, ill-assorted, often incomplete, often inaccurate—the blow to the head, you see—but a few containing enough truth to persuade those who needed to believe that yea, verily verily, Anastasia lived. Some relatives, those not intimately connected with the family and those who enjoyed little, if any, acquaintance, already declared this woman’s story to be true. Dr. Botkin’s own son verified her identity to his satisfaction. Were their motives dishonourable and mercenary?

An opportunistic line of light creeping in between the parted draperies reached as far as the bed and Olga gasped ... no, it couldn’t be ... so many killed at once, innocent children all, surely God in His mercy ... then Frau Tchaikovsky hid her face behind a raised hand ... the light hurts my eyes, she cried out in German. Olga admitted the possibility, just as she believed that unhappiness often distorted reality, that missing a person often made one see her double suddenly on a bus, or become friends with someone who resembled the beloved. Oh dear, this woman in her crudity and linguistic deficiency and conveniently fractured memory could not be Anastasia. As suddenly as it had arisen, the hysteria passed and the woman directly appealed to her Aunt Olga not to deny her, to remember the snowball, she cried out, when she put a stone in the snowball outside the palace and threw it at Tatiana?

“You used to call me malenkaya, remember, Auntie? Or shvibzik?

She mispronounced the Russian nicknames. True, the family often called Anastasia shvibzik because of her impish behaviour, something about how Frau Tchaikovsky recited the words suggested mere repetition of what she could have learned from any number of sources. Dear God, how painful to stand by the woman’s bed, for Olga could sit no longer, doubting the words spoken in a language Anastasia did not know, but yearning to embrace her sorrow and suffering. She had nursed wounded Russian soldiers, had held dying young men, boys really, whispering her name, their blood seeping through inadequate bandages. Oh, she had witnessed horror and had never developed a protective carapace around her heart.

Yes, yes, the weeping, Olga wondered how miraculous it would be if the woman’s story were true. She wanted to believe if only to bring an end to the dear soul’s unspeakable suffering. To be denied who you were, to be rejected by those who had loved you, after crawling through the muck and mire of history—what a nightmare! Those eyes, at least as much of them as Olga had been able to see, something there, the expression, a few facts not many would have known, but how to prove on shaky evidence, on derivative information: all the Romanovs lived amidst contingents of servants with eyes and ears and tell-tale tongues.

Olga asked the doctor questions about why Frau Tchaikovsky came to be in Berlin. What was the exact nature of her injuries aside from the obvious? Would she ever recover her Russian or speak English and French the way Anastasia used to: those child-like inflexions, the solecisms and non-idiomatic phrasing in English, despite Mr. Gibbes—gracious, Olga hadn’t thought of Mr. Gibbes in years—despite the English tutor’s insistence on correct usage, demanding linguistic perfection. No, the woman did not remember the tutor’s name. Yes, of course, amnesia, you see.

With a dismissive wave, Frau Tchaikovsky closed her eyes and said in German, “I cannot speak anymore. Please leave.”

The doctor sought to apologize, offering medical excuses, but Olga had not taken offense this time. She also wished to leave. Allowing the doctor to kiss her hand, a fawning gesture, she stood in the corridor outside the door, and heard the large intake of her breath. Her mind confused as if her own memory had suffered a blow, she could not think in any language she knew, just a whirl of yearnings and regrets, and hoping against hoping, mingled with unspoken prayers.

Of course, she would return tomorrow. The woman perhaps would be calmer, more rational, and they could speak. The Dowager Empress had refused to participate in the unholy game of pretenders, as she called it, and perhaps she had been right to do so. Sister Xenia also advised her not to be seduced by a pretender. And yet, and yet, one had to know, one wanted history to be otherwise, one sought an end of wishing and the painful void left in her heart by the murder of her family.

If murdered she had been. News had been partial, selective, facts scarce, rumour more rampant than truth. Who knew what had actually occurred, except the firing squad, and could their accounts be trusted, Bolsheviks all? Not only Anastasia, but pretenders also claimed to be Marie and the dear blessed, sometimes mischievous boy himself, heir to all the Russias. Frau Tchaikovsky was a deluded, tortured soul, desperate for attention and recognition, and had attached herself to the most dramatic personal story of the day to compensate for the tragic meaninglessness of her own life.

If a fleeting look in the eyes reminded Olga of Anastasia, if one or two facts escaped the woman’s mouth in German, if she recalled details of the tsar’s personal quarters, they collectively failed to build a sufficiently persuasive case. Grief made one wish to believe, and Olga quickly left the hotel room so as not to cry in front of the two strangers. She had struggled heroically against tears since her exile, since the appalling murders, but how easy to bend reason to one’s wishes, and how easy to seduce a compassionate or mercenary heart.

Olga decided not to return the next day, finding the quandary, her doubts, dismay, and half-belief too much to bear. So many relatives had denounced this woman without meeting her and she, Olga, had doubted first, then allowed desperate love to half-persuade, then faltering reason to dissuade: no, she could not correct history or corroborate this woman’s identity because momentarily she might have wished to do so. To apologize, Olga sent a gift of a scarf, an expression of regret and a wish that Frau Tchaikovsky recover her full health and spirits.

She returned to Copenhagen by train, careful not to bring up the subject of her trip to her mother whose disapproval chilled the morning tea, but she had confided in her sister, expressing her doubts, perhaps not as strongly as she should have, of the woman’s claims. And when the old Empress died three years later in 1928, Olga signed a letter along with several other surviving Romanovs including her Xenia sister to be published in newspapers that Frau Tchaikovsky could not be Anastasia.

Neither she, nor anyone else who knew Tsar Nicholas’s youngest daughter, was able to find the slightest resemblance between Grand Duchess Anastasia and the person who calls herself Frau Tchaikovsky.

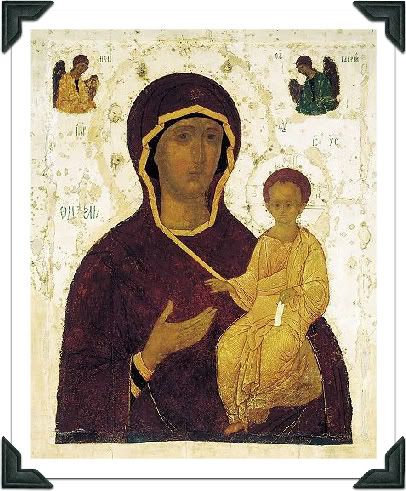

Alone at night in her bedroom Olga prayed before her favourite icon, praying not to be troubled by the dead miraculously arising from their grave, not to be tempted to believe in fantasy. Olga knew that issuing such a statement had been the proper thing to do. She only regretted that she had not been firm in that hotel room and instantaneous in her denial of the woman’s claim. Of pretenders there would be no end. Poor deluded Frau Tchaikovsky, poor murdered Anastasia.

Kenneth Radu's stories have appeared online in Foundling Review, Writers' Bloc (Rutgers), Two Hawks Quarterly, Poor Mojo's Almanac(k), and elsewhere. He is also the author of a memoir, The Devil Is Clever (HarperCollins Canada). He lives in Quebec.

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

Like any writer of fiction I am interested in the dynamics of human character. Within historical fiction, however, character should not be separated from the actual historical facts as we know them. We may imagine plausible scenes, given our knowledge of events and participants, but we cannot alter the known facts. For example, my character Olga was a Grand Duchess of Russia before the First World War, and not a Chinese empress. That is a simple indisputable fact and her characterization, therefore, whatever I have made of her, has been written within the context of her time and place. Similarly, if we are writing a fiction about Shakespeare, we know a few bald facts about his life so we are free to imagine his character and what he did. We are not free to divorce him from his social and historical setting, unless we are producing a fantasy. To answer the question, therefore, I would have to say that both the character of a historical personage and his or her relation to actual historical facts as we know them are the two most important parts of historical fiction.

0 comments:

Post a Comment