Scarecrow

by Michele Stepto

Once there was an Indian whose friends called him Wawanotewat, which means He Who Fools Others, because of his cunning in battle. When he grew old, he exchanged his tomahawk and scalplock for an English hoe and took up farming in the English style of his neighbors, hoping to live peaceably in the days that remained to him. There was no one but himself to provide for. His old wife had long ago gone to her rest, and his children were scattered to the winds. He had only a couple of stony acres along a meager river, but here he planned to grow enough corn to tide him through the winter.

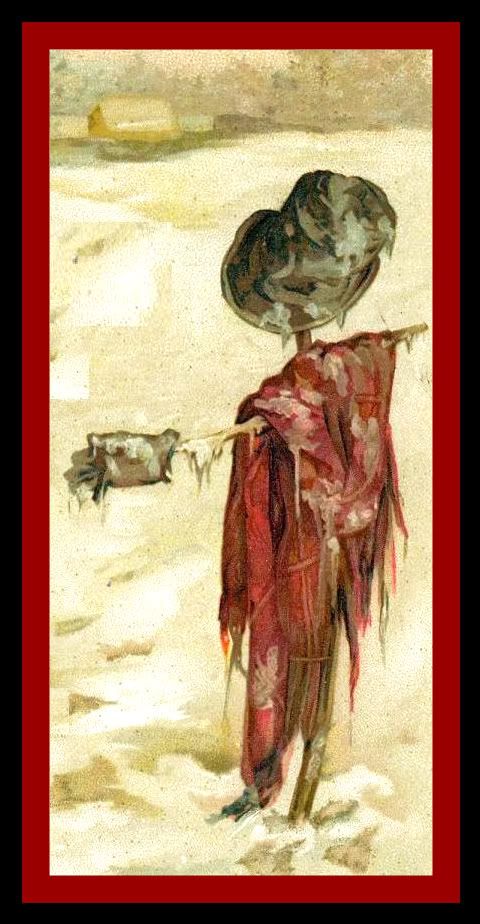

After he had planted his seeds in straight rows at the proper moon, he decided to build a scarecrow to defend his crop against the crows. He lashed together two stout sticks in the shape of an English rood, and having dressed this device in an old bonnet and linsey shirt and trousers and a worn pair of moccasins, he planted it upright in the center of his field. “Brother Scarecrow,” Wawanotewat said, “when the corn ripens and the crows come, explain to them that I am a poor farmer. They are rapacious, but they have the gift of reason. Allow them three kernels each, then send them along to the next field.”

Some time after this, Wawanotewat received the gift of a cloak from a well-meaning Englishman. It was a sturdy fustian cloak of the sort known as a “round cape,” such as the Jews of old Europe had once been obliged to wear to distinguish them from their Christian brethren, although the Englishman knew nothing of this. He had found the cloak in a rag shop in New Amsterdam on his sole trip to that city and, taken by its soft sheen and the miniscule stitches with which it was held together, and thinking it would make a fine Sabbathday garment, he had bought it. But his wife would not hear of his wearing it on any occasion, let alone the Sabbath. Examining the fine stitches, she pronounced the cloak the work of the devil. “And besides that,” she said, “it is no longer the fashion.” And so he decided to give it to his neighbor, Wawanotewat, in secret recompense for having coveted his land.

“Thee mun cover thy nakedness afore God,” the Englishman told Wawanotewat, but Wawanotewat understood very little of this. The words “nakedness” and “God” were not part of his little English. He did, however, understand the word “cover,” and as it was evident to him that the purpose of the cloak was to cover something, he decided to dress his new scarecrow in it. “Look what I have brought you, Brother Scarecrow,” he said, as he tied the cloak around the scarecrow’s neck. “It will keep you warm on the cool nights and dry when the rain comes. If the crows do not listen to reason, you have only to flap your arms and this cloak will scare them away.” Wawanotewat could see that the corn was well on its way by now, and he knew that it was time for him to repair to his summer fishing quarters. “I am leaving you in my place,” he told the scarecrow, and off he went to join his remaining friends at the shore, traveling through his neighbors’ fields and pastures by a secret map he kept in his head.

Now the scarecrow liked Wawanotewat, who had given him such a fine garment, and who always treated him with respect, and he was determined to do everything in his power to protect the old farmer’s corn. “Look at this man,” he said to himself, “taking up farming at such an advanced age and with nothing but hope in his pocket. If I do not protect this field, I am a brainless simpleton, unworthy of the name of scarecrow.”

In time, the corn ripened and the crows arrived and the scarecrow spoke to them in the voice of reason. “Brother Crows,” he said, “I am the deputy of Wawanotewat, whose field this is. Before you lies his entire wealth, the harvest of which must support him through the coming winter. He invites you to sup here, but begs that you content yourselves with three kernels each, and find the rest of your dinner elsewhere.”

The crows had never before been spoken to in such a dignified manner. They were used to the English scarecrows, who hurled foul epithets at them in their outlandish tongue, and to the English farmers, who put a bounty on their heads, twopence each, and went about trying to slaughter them all over the neighborhood.

“Who is this Wawanotewat,” asked the Crow Sachem, “who guards his field with such a honey-tongued servant?”

“He is an old man,” answered the scarecrow, “poor in substance but rich in kindness and resolve. In return for the favor he asks, he offers you his deep thankfulness, and pledges his help, in whatever way he can help, if you should ever need it.” The scarecrow had added this last promise because it seemed to be called for, although Wawanotewat had said nothing about such a pledge.

“We accept this agreement,” the Crow Sachem replied, and with that the crows each took three kernels of Wawanotewat’s corn and flew off to finish their dinner in a neighboring field. Wawanotewat had been right, the scarecrow thought. The crows were indeed creatures of reason. He had not even had to flap his arms.

But alas, the crows were not the only creatures interested in Wawanotewat’s corn. The Englishman who had given him the cloak soon noticed that his neighbor’s farm appeared deserted. He came over one day to see what was what, he looked inside Wawanotewat’s wigwam, he walked the boundaries of Wawanotewat’s field, looking for any sign of him. “The old man must have gone away,” he said to himself, and soon thereafter, with the help of his sons and sons-in-law, he began to build an English barn on Wawanotewat’s land.

The scarecrow watched this unfold with dismay. If he had known where to find Wawanotewat, he would have hopped off to warn him of the danger, but the scarecrow did not have Wawanotewat’s map in his head. He wasn’t even certain where Wawanotewat had gone. Every day the English barn rose, piece by piece, looking a little more complete as each twilight arrived, and every night one of the neighbor’s sons or sons-in-law returned with a lantern and flintlock to guard the new structure. This gave the scarecrow an idea.

One evening, when the darkness was complete, he hopped from his place in the cornfield to where the guard was sleeping and, flapping his arms, he cried out in his boomiest voice, “Away with you, you varmint from Hell. Satan is coming to claim his own, you wretched caitiff. Away with you now, or sleep forever in the fiery netherparts of the devil.” The scarecrow wasn’t quite sure what all of this meant, but he liked the sound of it, and he noticed that his words had an immediate effect on the startled guard, who grabbed his flintlock and lantern and sprinted away.

Wawanotewat’s neighbor had heard about such evil doings in stories when he was a boy, and he thought he knew what to do. He promised his sons and sons-in-law that whoever should defeat the demon would have Wawanotewat's land, and of course after that each son and son-in-law had to take a turn guarding the new barn. But every night, the scarecrow, warming to the task, sent each one scurrying off in terror of some altogether original and hellish fate, until he began to feel that his brain was teeming with rapturous invention and that he could go on like this forever, no matter how many sons and sons-in-law the English neighbor might send his way. He liked it best when one of them arrived with his flintlock already primed to fire. The shot, of course, had no effect on the scarecrow, though it did perforate his new cloak. “Villain,” he would moan, flapping his arms, “the grave is hungry, it yawns for you,” and with that the intruder would scuttle away into the dark.

In the end, when only the neighbor himself had not taken a turn sleeping in the barn, Wawanotewat returned, anxious to see how his corn was faring. He was surprised to find it grown tall and sturdy, unmarred by bird or beast, and even more surprised to see an English barn standing at the edge of his field where his wigwam had been. “We thought you needed a proper house,” his neighbor explained. “My sons and sons-in-law built it for you.”

Wawanotewat could see that his scarecrow’s beautiful cloak was somewhat the worse for wear. “I have you to thank for this prosperity, old friend,” he told him. “When winter comes, we shall keep warm together in this fine new house, and tell each other stories when the night comes on.”

All of this happened as Wawanotewat said it would. And more, for the crows also took refuge in Wawanotewat’s new house, driven there by the murderous bounty the English had placed on their heads. The scarecrow explained to Wawanotewat the bargain he had made, and the old farmer, understanding the justice of the arrangement, was happy to give the crows shelter, and to hear their stories and feed them from his store, which was especially plentiful that year.

Moccasins

by Michele Stepto

In the late winter of 1697, a party of Indians attacked the village of Haverhill in the Bay Colony, killing twenty-seven of its inhabitants and carrying off another thirteen into captivity. Among the kidnapped was Hannah Dustin, a large, robust woman of forty years. She had borne twelve children, the last only six days earlier. When the attack commenced, Hannah lay in her bed next to the sleeping babe, attended by her nurse Mary Neff. Outside, she heard the voice of her husband Thomas sounding the alarm. She hurried into a skirt and shawl, and had just put on one of her shoes when several Indians broke down the door and, laying hold of the two women and the infant, thrust them outside. When the infant began to cry, the man holding it dashed its head against an apple tree in the dooryard. The Indians then dragged the two women to where the rest of their party waited, with the other captives, and the flight began. Those who could not keep up were tomahawked along the side of the trail. Somewhere along the way, Hannah decided that she would travel more rapidly if she discarded her single shoe, a heavy, buckled affair, and ran in her stocking feet.

They traveled north twelve miles that first day, and in the week that followed another seventy-five, to a place somewhere in what is now southern New Hampshire. Here, their captors left Hannah and Mary in the charge of a small band of Indians, two men, three women, and seven children, with whom they were to continue north. Hannah was never able to discern in what way they were all related, but it was clear to her that they were a family of some sort. They prayed together three times each day, using the Latin prayers they had learned among the Jesuits, and they required the children to pray before they ate or slept. They did not insist that Hannah and Mary join in these popish practices, but would not allow them their English prayers. Hannah often went behind a tree to adjust the bands around her swollen breasts, which were tight with milk for her slaughtered babe, and here, in private and in silence, she would pour forth her soul before God.

Among this Indian band was a young couple, a husband and wife as Hannah surmised, and their newborn babe. The man was thin and slight, nearly hairless on his body. The woman was small and well-rounded, with bright eyes and a ready smile. Neither spoke much. She carried the babe as they traveled, nursing it from time to time along the way whenever it cried, while he kept pace close behind her. When they rested at night and the babe had fallen asleep, she took up a pair of deerskin moccasins upon which she was working. In a pouch slung around her neck she kept her tools and materials, and from this each evening she would shake out her fishbone needle and thread and some wampum shells, and by the light of their fire she would pierce a hole in each shell, twirling her needle back and forth between her palms. Then she would fix the shells onto one of the moccasins, overlapping them carefully to form a rosette. When she had finished decorating the first moccasin, she took up the second. Her husband watched her silently, always at her side. Hannah watched her too, thinking of her own bloodied feet.

Also of this party was an English boy named Samuel who had been captive for so long that he spoke the Indian tongue with considerable fluency. He often seemed engaged in spirited conversation with the apparent leader of the band. Once, Hannah asked him what they spoke of, and Samuel told her that Bampico—for that was the man’s name—had explained how he killed the English so quickly, with a swift blow of the tomahawk to the temple. He had also told Samuel that they were on their way to the praying village of St. Francis, in Quebec, at the gate of which the three captives would be forced to run the customary gauntlet, naked.

Two weeks out of Haverhill, they arrived at the Merrimack River where it is joined by the Contoocook, and here on a small island in the midst of the rain-swollen confluence they made camp, intending to rest for a day or two before continuing north. The canoes they used to reach the island they left along the shore. When they had eaten from their scanty store, the young Indian wife, her babe having fallen asleep, took up the moccasins a last time and completed the second rosette of wampum shells. She pulled tight and knotted the last thread, and without ceremony presented the moccasins to her husband, who doffed his old ones and put these on, nodding solemnly. Hannah watched, hugging her breasts. Her milk was dried up by now.

Perhaps because they did not think their captives would dare to attempt escape across the rampant waters, the Indians did not bother to post guard that night. When they had all fallen asleep Hannah got up, and waking Mary Neff and Samuel she gave each of them a tomahawk and, by means of sign language, indicated they were to kill their captors. She placed Samuel at the sleeping head of Bampico and took up her own position at the head of the young husband, leaving Mary to tomahawk his wife. When this slaughter was done, they moved on to the other women and the children. Someone’s blow went awry—was it Mary Neff’s?—and one of the women escaped into the night with a grave wound, but in a matter of minutes all the others lay dead, all except the newborn child. Hannah stood over it, her tomahawk lifted to deliver the blow, but thinking of the wound to her own soul she relented. The child was after all helpless against them.

They took the best of the canoes that lay waiting and scuttled the rest. Then Hannah remembered the Colony’s bounty on Indian scalps and, returning to the camp, she located a knife and removed a portion of scalp and hair from each of the dead, rolling these trophies into a bundle with a piece of cloth she tore from her shirt. From the body of the young Indian man she had killed first, she removed the moccasins with their wampum rosettes and placed them on her own feet. The man’s child was still there, still sleeping.

A few days’ travel downstream brought them to Haverhill. They slept in turns, never daring to stop, and every time the dark closed over her Hannah saw the Indian child she had spared, stirring in his wrappings, beginning to wake. At home, she attempted to remove the moccasins from her feet, but found that her wounds had dried fast to the leather. She took her knife and sliced through them, removing them in pieces, though this set her wounds bleeding afresh, but that night as she slept the moccasins were still on her feet, warm and whole. They carried her across her husband’s fields and into the bordering woods, and there, not too far within, she saw the Indian man and woman sitting with their backs against a tree, a papoose stirring at their feet. When Hannah approached to get a clearer view of the child, the woman reached out a ghostly finger to touch the wampum rosettes she had beaded, first one and then the other, and looking up at Hannah she nodded her head sadly several times. In the morning when she awoke, Hannah found the moccasins lying uncut next to her bed. She could see now that they had the shape of her own feet.

In a few weeks, when her wounds had healed and she was once again able to wear shoes, Hannah traveled to the General Court in Boston to claim her reward, bringing with her the ten scalps she had taken. The Court awarded her 25 pounds, with which she and Thomas planned to buy more land along the Merrimack. To Mary Neff and the boy Samuel they gave another 25 pounds to divide between them. Hannah also visited at this time with some of the luminaries of the day, including Cotton Mather and Samuel Sewall, who listened to her tale, the latter following the route of her travels on a map he possessed and noting the island where she had committed her acts, there where the two rivers converged. Contoocook Island it was called, though it would soon come to be known as Dustin Island. Hannah told them she had spared the child out of pity for her own murdered babe. From the notes he took of their meeting, Mather later constructed the scene: “Only one squaw escaped, sorely wounded, from them in the dark; and one boy, whom they reserved asleep, intending to bring him away with them, suddenly waked, and scuttled away from this desolation.” Some few who heard the story wondered privately what chance of survival the child had had, though most laid this particular episode to Hannah’s credit.

And after awhile Hannah herself began to believe she had truly spared the child, and began to wonder if it had indeed survived. Perhaps the wounded squaw had returned to save it. But if so, who was the child in the woods with the Indian couple? Was it their dead boy? Or her own murdered babe, whom a just God had entrusted for eternity to those she had murdered? Many times the moccasins carried her into the woods, to where the man and woman sat with the child at their feet, but she was never able to come close enough to make out the child’s identity. It was swaddled entirely, head to foot, and Hannah dared not move aside the woman’s hand, where it lay on the child’s head, in order to see its face. At length, the man and the woman and the child fell into dust, along with the moccasins, and Hannah understood she would never know the truth.

As an old woman at her “eleventh hour,” as she wrote, and being sensible that it was her duty, Hannah craved admittance to the church. “I am Thankful for my Captivity,” she declared in her petition, “twas the Comfortablest time that I ever had.” And this was true, for all her moments since had been unquiet.

Michele Stepto says: I have taught in the English and African-American Studies departments at Yale and at the Bread Loaf School of English in Vermont, and have published a translation from the Spanish of the Catalina Erauso memoir under the title, Lieutenant Nun: Memoir of a Basque Transvestite in the New World, along with works of history and fiction for younger readers. An earlier short story, "Pagoda," appeared in the magazine Italian-Americana.

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?

For the writer, the genre of historical fiction can be liberating. The contemplation of other times and places releases the imagination from the often tedious business of being true to one's own time and place. That is perhaps its chief attraction! The genre also allows us to bring to life a place we may have visited (through books or travel) and come to love —for me, Pienza is such a place—to exist within it as something other than a tourist, to imagine a life for ourselves there. I think that for the reader the pleasures of historical fiction must be the same: it frees the imagination from the here and now, allowing it to ramble elsewhere.

0 comments:

Post a Comment