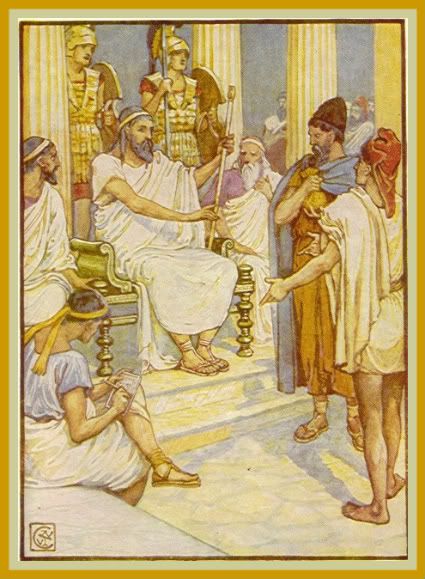

The Last King of Athens

by Owen Dando

"...such was the nobility, gentlemen, of those kings of old that they preferred to die for the safety of their subjects...That at least is true of Kodros..."

I'm no hero, Kodros thought.

The Dorian army stretched from the walls of Athens to the distant sea, a shimmer blurred by summer heat and the smoke of forges. A myriad soldiers bustled like ants through the enemy camp. Kodros could not clear his mind to think. His ears were thick with the clang of hammer on anvil.

"My Lord." Medon joined him on the ramparts, nodding a solemn greeting.

Kodros swallowed and loosened his fleshy, ringed fingers from their grip on the parapet. He clenched his hands together to stop their tremor.

"The foreigner is rewarded?"

"Yes, father. We gave him gold."

I should have run the treacherous runt through before he had chance to speak, Kodros thought.

"And his message?"

Medon looked away. For a few moments he was silent, then drew a long breath.

"It is the word of the god."

Kodros examined his son as the young man surveyed the enemy. That noble profile etched against the azure, that strength, poise and charm – Zeus, people talked of the boy as if he were Herakles reborn. Today, as ever, he wore a poor man's homespun chiton. No doubt he would discard that for fur-lined robes once he had grabbed the throne, Kodros thought.

"Come, Medon." He gave a sour laugh which caught in his throat. "You speak as if I were already dead." You do not have the crown in your hands yet, he might have added.

The invaders had surged and swarmed from the Peloponnese without warning, laying waste to Arcadia, Corinth and the Argolid, to all that stood in their path. Now they infested the Attic plain, starving Athens into submission. The ruin of the besieged city was certain.

And we delude ourselves that we have a chance, Kodros thought. He cursed again.

After pitching their camp, the Dorians had sent ambassadors to question the famed Oracle at Delphi. Unknown to them, an oily little man named Kleomantis had stolen away to Athens, to report the fatal augury and claim his prize. According to this wretch, the priests had prophesied that either the city would fall, or its king would be slain. The death of one meant safety for the other. So said the Oracle of Apollo.

The people, Kodros thought – that mob – will expect a great deed of me. And how convenient this revelation is for my son.

Kodros looked out once more over their countless adversaries. Prophecy or no, the Dorians' victory was assured, whatever futile action he might dare. Only credulous fools would turn away when the richest prize of all was within their grasp. The king sank forward on his elbows against the battlements, forehead in hands. The rhapsodes might sing that heroes would feast forever in the sweet breezes of the Elysian fields, but he knew otherwise. The gods were ghosts, and the holy men of Delphi mere men, who told venal lies. His death would make no difference. Kodros would have none of it.

"Leave me, Medon."

His son bowed his head then departed, as graceful as ever – and as odious. Kodros ran his fingers through an unkempt beard. If only he could find a thread to lead him out of this maze. He looked down to the foot of the city walls. Here, near the western gate, thickets of brushwood dotted ground which fell away towards the enemy camp. On these slopes, in peaceful times, the rabble would gather fuel for their fires.

The king had an idea.

The next morning, at the hour before dawn, Kodros slipped from his bed and the cold embrace of his sleeping queen. In the antechamber, faithful Philopatros awaited. The king took from him a fetid, flea-ridden cloak and a farmer's sickle that his servant had procured. He looked into the old man's watery eyes.

"Not a word now, slave."

He fastened the sickle to his belt. This was no weapon for a nobleman, but its sharp edge gave him some comfort. To believe the Oracle, he should be safe from harm. Kodros, however, had no intention of venturing outside the walls unarmed. At his other side he secured a heavy pouch of gold, removed late last night from the city treasury, then wrapped the noisome cape around his belly.

Kodros dismissed Philopatros with a flick of the fingers, and stole away through his palace. All was still. He crept through dark and silent corridors, to escape the royal compound through a servants' entrance. The king checked the way ahead was clear, then, with a shudder, drew the cloak's filthy cowl over his head. His disguise complete, he made his furtive footsteps light and soft as he hurried through the streets.

At the western gate, Kodros spun a tale of a poor man's need for kindling, taking care to keep his face hidden. He had feared the guards would argue, and held a gold piece in his palm, ready to buy their complicity. But the men obliged without complaint and unbolted the locks. Kodros was out.

In the east, the saffron of dawn lit the sky, yet the enemy camp was still quiet. Kodros edged down the hill away from the city walls and picked up the odd branch and twig, acting the part. He glanced back at the gatehouse barbican, which teemed with sentries today, of all days. It would not be long though, Kodros thought, and he would be out of sight and free.

And then where to? Orchomenos? Or Thebes? It did not really matter. Kodros would live a while longer yet, and his gold would buy a fine retirement. Let Medon take the throne that he craved – perhaps he would not enjoy it for long. The king skirted a dense growth of bush, drifting further from the city's watchful eyes.

"Houtos! Hey, you – peasant!"

Kodros turned in alarm. Two Dorian soldiers were striding towards him. This was not part of the plan. Without another thought, he threw down his gathered wood and began to run. He soon had cause to regret all the years of fine meat and drink, and the weapon and gold at his waist weighing him down. Fire burned in his chest as he stumbled over the stony ground. Yet the clank of armour came ever closer behind.

"Stop – stop, peasant!"

A hand grabbed the king's arm, spinning him around. Kodros staggered back a step, then doubled over, hands on his knees. Sweat poured into his eyes, and his breath came in pained heaves. The soldiers were laughing at him.

"We only want to ask how it goes in the city, farmer. We don't kill fat, old men for sport."

The Dorians insulted him in that barbaric dialect they dared to call Greek. These damned insects were not fit to even look at a true Hellene, Kodros thought, let alone a king. Their insolence was intolerable. Kodros dragged himself upright, reaching within his cloak for the hidden sickle. And to his own surprise, with a swift sweep of the arm, he cleft the shorter man's head clean from his shoulders.

The lifeless body slumped to its knees, then pitched forward to thump the ground. Kodros stared at the blood dripping from his weapon. The second soldier, too, was still for a moment, his eyes wide. Then he pulled his steel sword from its scabbard with a cruel whisper. Kodros trembled, hefting the sickle in his hand, as the Dorian advanced on him. Then the sound of tumult from behind made him turn. A crowd thronged the walls of Athens, punching their fists and yelling.

Philopatros, he thought. The cur betrayed me.

A heavy boot slammed into his ankle and Kodros crashed onto his back. The breath exploded from his lungs. His elbow cracked against a rock and the sickle slithered from his grasp. He tried to struggle to his feet, but the soldier kicked his legs from beneath him again, took his sword in two hands, and lifted it above his head. The king squirmed backwards as the crowd gave a joyful roar. Kodros whimpered.

The scum are cheering my death, he thought – no, wait–

A few days later, Medon stood once more on the city's ramparts, the wind toying with his thin tunic as he looked over the Attic plain towards the sea. A blackened patch of burnt grass here and there, a cart abandoned – this was all that remained of the enemy camp. The Athenians had sent heralds to reclaim the body of their king. Not long after, the last of the Dorian invaders had fled south across the isthmus of Corinth, back to their homeland.

Medon understood. He could not condemn them for cowardice. Only those cursed by the gods to die would ignore the words of Apollo.

In the necropolis, the foundations lay for a fine new tomb. Here Kodros would rest, buried along with the ancient crown of kings. For the royal line was ended: after such sacrifice as his, no man, Medon had declared, could be worthy to succeed his father. From this day, Medon and his fellow magistrates would rule the city together. Such was their monument to the immortal valour of the last king of Athens.

Owen Dando lives in Scotland amidst an uncontrollable collection of books, and writes historical and science fiction. This is his first published story.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

I think that writers of historical fiction are lucky in that ideas abound - you only need open any page of a history book or visit a historical site to find them. For me the difficulty, and also the joy, of writing is the molding of these ideas into stories.

0 comments:

Post a Comment