Resurrection

by Doreen Perrine

I stumbled toward the abbey, my last hope of refuge, in a feverish daze. Each cough stabbed my chest with wintry air and I braced myself to face them. I could either beg or die, forgotten in the frozen night. In the wake of these latest Protestant uprisings, I was no heretic. Neither was I a whore. In truth, I didn’t know what I was—I only wished to live.

My head bowed, I tugged the stiff rope to ring their bell. The door creaked and I shielded my eyes from the candle’s flame. “Mother cast me out.” The plea dripped with spittle from my cracking lips.

“We won’t trouble the parish doctor.” The Abbess’s voice was as shrill as the icy wind. Still, she suffered to take me in.

I could work beside their hearth just long enough to recover. Though grateful for her charity, I would have walked away if not for my illness. Even the air of that place, clotted with stale incense, suffocated me.

The Abbess, her drawn face masked by the shadow of her hood, led me down a corridor. She left me in the kitchen, where I donned the apron a scowling old woman thrust at me. “Fetch wood!” she growled in a thick accent.

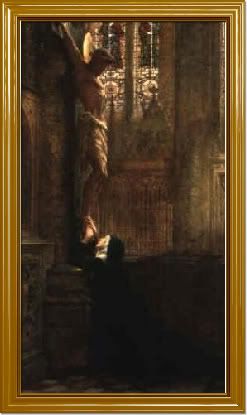

True to my mother’s judgment, I felt sorry for myself. Hauling the crate from the woodshed to the kitchen, I paused before the chapel. A skeletal figure crowned in thorns hung in the midst of the sisters, seven in all. They mumbled their Rosary at the twisted feet of the sculpted Christ. With his sides dripping in slits of painted red, his lot appeared harsher than mine.

You are only a statue. I thought the rebellion I dared not utter. By silence alone would I survive in that dying man’s world.

Later, I undressed in the sparse back room they bid me to sleep in. In the deathly silence, I stretched my aching body on the rigid cot until day burst in.

“Up, good-for-shit and stoke the fire!” Gerta the cook spat at me.

Even this foreigner was better off. If only she understood. Not labor so much as tedium weighed like a millstone around my neck. At twenty, I longed for something more, something meaningful.

Forcing myself to rise, my thoughts clung to a sweet dream.

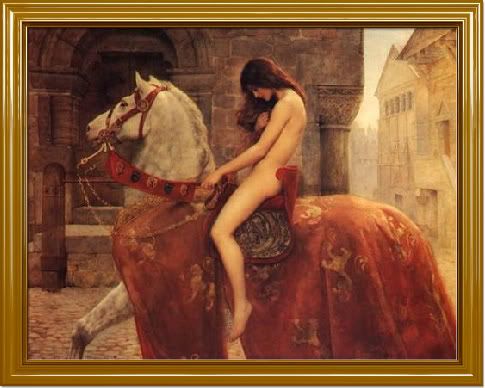

Straddling an unblemished mare, I rode naked across a flowing field. We trotted across the grass spotted with blinding yarrow toward a wild forest. But what was this bliss that pulsed between my legs?

The black mare tilted her head, aglow with sunlight, to smile back at me. I buried my face in her silken mane, then realized—it was spring. Come spring, I would either forsake this place or take my vows.

Lifting the ragged hem of my frock, I trudged the slushy path to the woodshed. I cringed at the chilly wetness that soaked my threadbare shoes. My cough echoed in the still air and, lest I wake the sisters, I bit my lip until it bled.

I felt in the dark for each log’s dryness, then loaded the crate. My eyes fell across the frozen field, a sheet of frosted white. Other-worldly, it glimmered in the blue-gray streak of early light. “I could die there,” I whispered.

I shook the grim notion from my head. Wait for spring, I reminded myself. Spring, like resurrection, may bring better fortune.

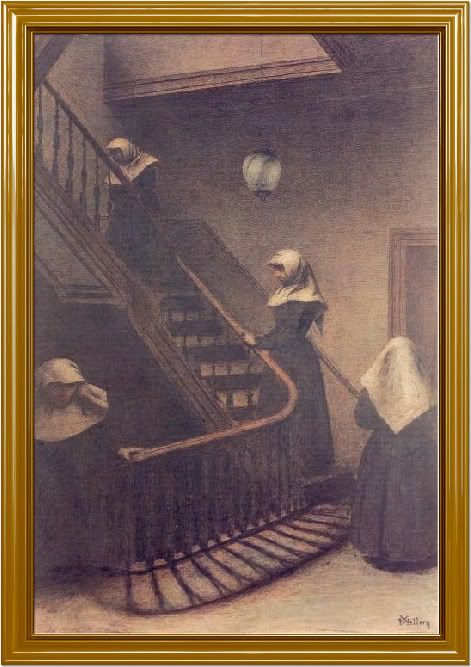

From then on, I studied the sisters’ synchronized steps—genuflection, the right to left sign of the cross—each sanctified gesture. Watching the nuns, I sought to advance my station from servant to novice. My brief but disastrous life had taught me one thing. I was no serving girl.

Too cheeky. Mother had sized me up at eight. I questioned too much. My domestic skills were paltry at best. Since childhood, I loved numbers and staring into the voiceless face of a deep, night sky—unfit occupations for a “lowly girl.” Was I good for anything? Certainly not matrimony.

I sighed to think of my fruitless engagement to the blacksmith’s son. Kindly enough, the man’s rough hands and the stubble of his bristly beard repulsed me. For shame at my refusal, my mother had locked me out in the snowy night. I felt more than heard the hard click of the latch inside the door and the echo of my cry, Mother, in the deaf street. Surely, I paid for the sin of my “fussy ways.”

Yet they were my saving grace among the nuns. A fortnight after I’d arrived, they held a taper between my quivering thighs. I gritted my teeth against the heat and wondered what they saw down there.

The Abbess peered through her spectacles, then concurred. “This girl has never known a man.”

And so I began my novitiate.

Too soon, the calling I undertook by mouthing their empty rites felt numb on my lips. The monsignor complained I did not confess enough. Beyond my secret disdain for bleak ritual, what should I confess? While I prayed more and labored less, white robes swallowed my body in a gaping void. I felt my youth drain in a bloodless swell as the walls of that tomb closed in on me.

* * *

Then, in the wake of Easter and my twenty-first birthday, she came. Phoebe, her name meant light and she rose, a blazing dawn over my dismal world. I longed to bury myself in the lush green folds of her velvet dress. Her flaxen hair, braided in a twirling crown, appeared feathery with wispy strands. Would she fly away?

“Who is she?” I craned my neck to face my elder, the towering Sister Claire.

“She is the daughter of an important benefactor of this parish. Don’t disturb Miss Phoebe!” Her sharp brows arched like sickles on her forehead. “She is here for penitence.”

I led Phoebe, whose plush dress rustled on the stone floor, to the room we would share. She flung off her cloak, then flopped on the other cot with a dramatic sigh. Her green eyes flashed as she met my gaping stare.

Then she crooked a ringed finger at the statue mounted over our cots. “Is this a friend of yours?” she joked.

“The Virgin, yes.” I blushed at my laughter.

I inhaled Phoebe’s powdered scent and secretly vowed to disturb her. She could exalt or ruin me—I didn’t care.

“Why are you here?” I asked in a timid whisper.

“My antics have caught up with me.” She shrugged at the slanted ceiling. “No matter. I’ll be home before Ascension Day.”

What could she mean?

“Mmm, not her first penitence.” Gerta smirked as we prepared supper that night. “She is a pig-headed devil, like you.” She wagged a slotted spoon at me.

Phoebe had refused the hand of not one, but several prominent men.

“Not like you,” Gerta glanced with a brief look of pity, “her father’s wealth buys her absolution.”

Later that week, I woke hacking bile. Three months since I had come to this place, my feeble lungs took a toll. I apologized for waking Phoebe, who followed me to the outhouse. There, the sisters wouldn’t hear me cough.

It’s charitable, Miss Phoebe, but you must watch her kind. I imagined Sister Claire warning her. Tossed between the fleshly world and this barren life, I was neither their sister nor their slave. As always, I was there to serve and, if anything, I knew my place.

After spitting up congealed brown mucus, I turned to Phoebe. “Leave me for dead.”

She simply stroked my back and smiled. Her pink lips shone in the full moonlight. I smiled, too. Not all darkness was evil.

At dawn, she held a cup of black liquid to my lips.

“What is this?” The question stuck to my parched tongue.

“Tea from nettles I plucked in the field. A peasant girl brewed it once for me.”

I sipped the bitter liquid and fell back in her arms. “I am a . . .” peasant, I began to say, but stopped myself. Really, I was nothing now.

She rocked me until I collapsed into a heavy sleep. If I were about to die with her by my side, this seemed like a blessing.

Then, in a hazy half-dream, I felt the crush of countless stones. Pinned to solid earth, my breath quickened in fierce spurts. Would I ever rise again? Three days Christ lay entombed in stone, but, first, he descended into hell.

“Am I alive?” I woke panting and sprawled across my cot.

As I mused on the dream, a childhood memory emerged. A woman from my village, accused of loving another of her sex, had been pressed to death. Had Catholics or Protestants condemned her? I could not recall.

“You live.” Phoebe clasped my trembling hands as sunlight filled the room.

Soon after, Sister Claire’s stern shadow darkened our threshold. “Monsignor hears confession today. Go mop the church floor!” she commanded.

I sat up, but Phoebe held me back.

“She cannot rise today.” Her firm gaze rivaled the sister’s glare.

We laughed into the blanket when she left.

“I could . . . never speak . . . like that.” I forced the words from my hoarse throat.

“You’ll learn.” Phoebe wiped my sweaty brow with an embroidered handkerchief. “I’ll teach you,” she whispered into my left ear.

But she must have seen. The flame of my defiance had been extinguished long ago.

* * *

We rode the speckled mare across the golden field. The doctor Phoebe had summoned to examine me insisted I rest and take the air. We passed the sisters hunched over their weeding in the vegetable patch. As if they drove nails into my sides, their hard stares pierced me through. Somehow I didn’t mind. Who among them, I wondered, had even glimpsed the joy I felt?

Lifting my head to face the open sky, I inhaled. Spring air fluttered in my lungs like wings of flight. I pressed my jostling breasts to Phoebe’s back and tightened my grip around her waist. I no longer wished to be a dead man’s bride.

The horse climbed the slope behind the abbey. There, a forest path split into dirt rows that had been hewn by the tread of wagon wheels. We dismounted near a shady patch where the mare wandered to chew on scraggly grass.

“The sisters won’t be pleased if we let her stray.” I fretted.

Phoebe shrugged. Her father, I supposed, owned a stable full of horses.

Between the trees, I looked down on the valley veiled in morning mist. A cluster of farms spread across the pale green plain. Their square plots appeared to fend off the encroaching savagery of wild forest. No ritual in untamed woods, I thought. Past the farmland, a broken ring of scattered slabs could only be the village graveyard.

Out of its midst rose the stony spire of the bell tower, its pointy top like fingers stiff in prayer. I squinted at the buildings of my old home huddled around the church—a strangely tranquil picture of the place that had given me up for dead. Just outside the village, I spotted the outstretched arm of a large hickory. The roadside tree, I knew, was a common site for hanging horse and cattle thieves. I looked away.

We settled on a rocky outcrop and I followed Phoebe’s distant gaze. Above the mountain range, a flock of birds soared in glowing air.

Phoebe turned to me. “I always wondered if my mother went to heaven. She was a good, almost saintly woman who did everything her husband and the church expected. So why should I question that?”

She tilted her head, her look solemn as though I could answer. Then she faced the view. Mountains might make a better reply.

“My mother died in the throes of childbirth at my age now, twenty-four. I was six at the time. Two days before Christmas and everything went white. Snow covered the ground as if to make it new.” She sighed. “Her death forgave the merciless world.”

I shifted closer to hear Phoebe’s fading voice.

“She bore my brothers, three, and me. I grew up engulfed by men, stomping about. I remember clinging to my father’s boot like he needed to walk for me.” She laughed. “I longed for women’s softness, yet secretly desired the life of a man, to do as I pleased.” She furrowed her dark brows. “I suppose no mother would have granted a girl child that. And marriage . . .” She shook her head. “The curse that drove her to an early grave held . . . still holds no appeal for me.”

I stared down, not meeting her intense eyes, their green dazzling in early light. “We always wish for what we cannot have,” I mumbled as if speaking to my lap.

“But why can’t we take some pleasure in this mortal life?” She pouted with a girlish frown.

Again, I had no answer. For the first time I asked myself, what did Phoebe want of me? And what was this power she held over me? Witchery?

A sudden breeze rustled the leaves. Loose strands of her flaxen hair fluttered as she leaned toward me. “This wind is for us.”

Her whisper tickled my ear and I smiled. Gently, she held my chin and pressed her lips to mine. A kind of hunger seemed to stir from some fetal part of me; alive but unborn, clinging to shadow—a precious being I had never allowed to breathe or see light.

I touched her smooth cheek and drew her in a snug embrace. My heart throbbed with an awakening I had never dreamed existed—not in me. We kissed once more and I felt my hunger burn, a fiery brand across my lips. Life, I pondered the unthinkable, might be a blessed thing.

She laughed aloud as I fell back, too stunned to speak.

That evening, Gerta snarled at me. “Beware.” She narrowed one wrinkled eye.

I rolled up my sleeves, then thrust my arms inside a bucket of chilly water. They’d piled the laundry in a heap—punishment, of course. I had been having too much fun.

“Beware of devils in fancy clothes.”

I shrugged. “No one is a devil here.”

Scrubbing the sisters’ soiled garments, I wished they were lace and satin like Phoebe’s.

“Hmph!” Gerta snorted. “She’ll leave this place and, you, they’ll toss away. Who will take you then?”

Her guttural words struck me like a blow and my tears dripped into the soapy water. Now that I’d begun to heal, death, that voracious beast, snapped its jaws at me. I was still prey.

That night, Phoebe cried my name. “Janine!”

Through the slit of our window, the quarter moon lit her tender blush. Cold stone pinched my unshod feet as I tiptoed across the floor. Under the Virgin’s maternal gaze, I knelt to watch Phoebe in sleep. As if the moon kindled my senses, I inhaled the perfume of her sweet, soft breath.

“Why not love in infinite measure?” I whispered the prayer. Why love in only one predestined course? It could not be right.

In the morning, Phoebe slammed our door with a clapping thud. Startled by the noise in that silent place, I dropped my folded nightshift and swerved.

She flung her arms around my neck, then waved a letter like a triumphant flag. “Once more, Papa forgives me!”

“What of your refusal to marry?” For this, my widowed mother would never take me back.

“My father has his lazy sons to secure his progeny.” She winked. “Since Mother’s death, it fell on me to save him from drink and debt.”

I hung my head. “I don’t know what it is to be . . . needed.”

“I need you.” She raised her eyebrows, then ran her hands across my breasts.

I flinched, not with guilt or fear, but with the bliss I’d felt in my dream. My body, a lifeless lump of clay, awaited the right hands—hers—to shape me.

That week, Phoebe prepared to leave. As she wrote her father, she would bring along a secretary to help manage the estate.

“I showed some skill with numbers as a child.” I half-smiled.

“Mmm, you are no slacker,” she wagged a playful finger, “but no more lugging logs for you!”

I sighed, a sigh of deep release. Had the Holy Mother heard my prayer?

On May Day, we made ready to depart. After our last breakfast, the sisters bade us farewell with slight nods. Only Sister Claire chided my “disgrace” in forsaking the veil. While the others said nothing, even the Abbess must have understood—I was never one of them.

I washed the dishes once more for Gerta’s sake. She bustled around the kitchen, not speaking to me. What could she say? I had crossed the gulf of my invisibility.

I helped Phoebe pack her things. Other than the green dress she’d given me, I had nothing else to take. We carried her bags toward the front door where I had arrived in a fever four months—and another lifetime—before.

“You’re grinning like a little girl.” Phoebe smiled.

“It can’t be helped.” I giggled at the happy sound of the carriage that would whisk us both away.

We stepped past the chapel where the sisters had begun their morning prayers. The nuns, their hands shrouded in black-white robes, moved alongside the pews. With the beads of their rosaries clinking, each knelt to cross themselves in silent air.

Phoebe touched my shoulder. “I’ll wait outside,” she murmured.

I nodded, then turned to face the crucifix. With none of the usual, servile gestures, I simply bowed my head. I summoned my respect for their Christ—not on the terms of the callous world. He died for love and for that I paid homage.

* * *

Doreen Perrine has been published in anthologies and literary ezines including The Copperfield Review, GayFlashFiction, Harrington Lesbian Literary Quarterly, The Queer Collection, Sapphic Voices, Queer and Catholic, Raving Dove, Sinister Wisdom, and Khimairal Ink. Her novella, Phendar of the Avila, a fantasy has been released in ebook form on Freya’s Bower. Doreen’s plays have been performed at Here Arts Center, WOW, Under St. Marks Theaters, and Manhattan Theater Source in New York City. Also an artist and teacher, she founded a local writer’s opportunity where she resides in the Catskills region of New York. Doreen’s website is http://doreenperrine.tripod.com/.

What advice do you have for other historical fiction writers?

I am attracted to the expressive means of historical fiction to breathe life into the past as an evolving dynamic that mirrors, like a looking glass world we step into, our present. Writers of this genre are in exceptional company and my humble advice is to create passionate heroes, if only of the everyday variety, readers will care about and remember.

0 comments:

Post a Comment