Roman Sacrifice

by Jasper Burns

It is springtime and Rome is at war. The emperor Caracalla marches his army from town to city, harvesting provisions and new recruits. Soon he will turn east into the Parthian Empire in search of spoils and glory.

Meanwhile, a messenger named Postumus steers his galloping horse through a mountain pass, carrying a letter to the emperor from Rome. The road turns south along the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean, then to Syria and the imperial palace in Antioch.

An officer of the Praetorian Guard meets Postumus at the palace gate. “This will be important,” he says. “From the prefect himself and under his seal. The empress will see you at once.”

Postumus is disappointed. “The emperor is not in the palace?”

“No, he’s with the army. His mother is in charge of things here.”

Julia Domna is more powerful than any Roman woman before her. For most of the past ten years, the warlike preoccupations of her husband and son have left her to administer the empire. While they chased barbarians and caroused with the legions, she received embassies, settled disputes, attended to the public welfare. It is a role that she plays with grace and skill - while still finding time to pursue her interests in literature, art, and philosophy.

Julia was only seventeen when she left her native Syria to marry the upcoming senator Septimius Severus. They quickly had two sons—Bassianus, later to become known as Caracalla, and then Geta. Julia and her infants followed Severus as his career took him from Gaul to Sicily, and then to Pannonia in southern central Europe.

Just four years after Geta’s birth, the emperor Commodus was assassinated, launching a power struggle that shook the empire to its foundations. This was a situation that Severus, by then a provincial governor and commander of a large army, was born to exploit. Over a period of four years, he outmaneuvered, manipulated, and finally annihilated his rivals, consolidating absolute power and abandoning the egalitarian tendencies of the emperors of the preceding century.

* * *

Julia’s appearance fascinates Postumus. She is in her late forties, but she looks much younger. Her almond eyes and arching brows are emphasized with indigo. Her lips and cheekbones are rose petal red and her nose, brow, and chin sparkle with gold dust. There isn’t a wrinkle or white hair to be seen.

Her dark brown coiffure is elaborate – row after rigid row of deep parallel waves, framed by braids that loop from her shoulders over her ears to her temples, with a large, braided bun pinned up the back of her head. Her ears and wrists and chest drip with gold and jewels - they chime and rattle when she moves. Her fragrance drifts over the crowd, creating an almost religious atmosphere. She holds a scepter of ivory and gold.

Postumus is so impressed that he forgets to give the message to her secretary, who plucks the canister from his hand, offering it to the empress. She sees the seal and stands up immediately. The soldiers in the room snap to attention and her attendants scurry to follow her out of the room.

Trailing silks, Julia enters her chamber. She pulls off her wig and tosses it onto a dressing table. Underneath is a purple scarf that covers her dwindling gray locks. She scoops two handfuls of water from a silver bowl and wipes the paint from her face, revealing a gaunt, yellowish countenance. Her proud aquiline nose looks bony and pale, almost translucent. She falls onto a couch and grips her aching breasts, feeling the jagged marbles within.

Julia Domna is dying. She knows she is dying.

Her sister Julia Maesa enters the room, kisses her cheek and takes her hand. “How do you feel, my dear?”

“Like a road where an army has passed.”

“I hear that an urgent message has arrived from Rome. What is so important?”

Domna hands her the case. “I haven’t read it yet. Read it to me.”

Maesa breaks the seal and pulls out a scroll. “It’s from Flavius Maternianus. ‘Hail, Caesar, blah, blah, blah. The African sage Nomenius has predicted that the praetorian prefect Marcus Opellius Macrinus will succeed you as emperor. I have summoned the seer to Rome and questioned him very closely. I believe that he is genuine. He says that Macrinus is already plotting your murder. Caesar; you must look to your safety.’”

Maesa stops reading: “This is serious, my love. Caracalla trusts Maternianus. Before he left Rome, your son told him to have soothsayers consult the shades of the dead about his fate. Where is the messenger? We must send him to the emperor at once, to warn him!”

The secretary moves toward the door, but Domna raises her hand: “No! Wait.”

She pauses.

“Leave us now, all of you.”

The servants hurry out of the room. The empress looks closely at her sister, choosing her words carefully.

“The festival of Jupiter Victor is one week away. You know that my son intends to conquer Asia as far as India in the coming campaign, so he will do special honor to the god this year. I believe that he plans to sacrifice hundreds, perhaps thousands of innocent souls for this purpose, just as he has done before in Britain, Rome, Germany, Rhaetia, Pergamum, Alexandria.”

Maesa’s jaw drops open. Her sister has never before spoken of her son’s atrocities. It is a secret known by many but uttered by few that Caracalla has ordered the massacre of thousands of people. The present war with Parthia began when he pretended to marry the Parthian princess, then murdered hundreds of unarmed wedding guests before the ceremony could proceed.

Domna looks intently into Maesa’s eyes. “We can stop it from happening.”

“How?”

“By seeing to it that Macrinus hears the prophecy before Caracalla does. Macrinus will expect to be executed, so he will find a way to kill my son first. All those lives will be saved.”

Maesa is stunned. She falls into a chair. “You could do that? Let your own son be murdered?”

Julia cannot say yes, but she cannot say no, either. “He becomes more brutal every day, Maesa. When I am gone, there will be no one to check him. His massacres will be even more frequent and terrible. He believes that human sacrifice brings him divine powers. There is no changing his mind.”

After a long silence, Domna asks, “When was the letter from Maternianus written?”

“Four weeks ago.”

“Then we have a little time before word can reach either Caracalla or Macrinus. We have time to think. Summon Philostratus, would you? I want his opinion.”

Caracalla stretches out under the stars, his long red cape for a blanket, a leather pouch for a pillow. He peels off his wig of short knobby blond curls and places it on his helmet beside him.

“Bald at twenty-eight—how the gods insult me!” he thinks. “Despite all I have given them, too. But I’d rather have victories than hair. When the world is mine, I’ll cut a throat or two for my scalp’s sake.”

He laughs at himself—what a scandalous thought! “What would my mother say?”

The emperor is proud that he lives just like any common soldier—but he is the only one with twenty German bodyguards camped in a circle around him. Despite their protection, Caracalla arranges his sword close to his side and checks it often.

Caracalla is in no hurry to sleep. He knows that nightmares await him: his father’s furious shade, his murdered brother Geta’s dying grimace, his mother’s contempt. And there are other visitors, too: slimy beasts from northern bogs, dire shades from the desert. Sometimes he dreams he is drowning in a dark sea that smells like blood and swarms with sea monsters. Caracalla hates the night; asleep or awake - the world lurks with demons.

A shiver runs through him. He touches his sword. Perhaps the moon god will protect him?

“I will give him the fairest flower of the city of Carrhae. I will bathe his shrine with their blood!”

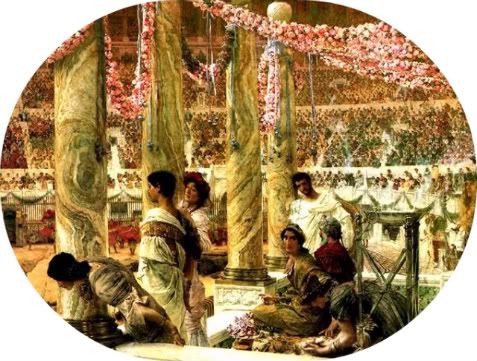

Caracalla feels comforted by the thought and is able to sleep. When he dreams, it is of Alexandria. Of his triumphal entry into the Egyptian city that he believes he founded in another life – as Alexander the Great. He can smell the incense, hear the drums and cymbals, see the flower petals showering from the rooftops. He watches himself climb the steps of the stupendous temple of Serapis and make offerings.

And there is the tomb of Alexander. He sees the conqueror’s crumpled face, grimacing in a honey-filled crypt. Caracalla removes his rings, his cloak, his gold-studded belt, and lays them on his hero’s tomb—offerings to the one destiny that he believes is both Alexander’s and his own: world conquest.

The dream shifts to a vast outdoor gymnasium, surrounded by colonnades. Thousands of young men are laughing, struggling in their drunkenness to stand in formation. They are exultant; the emperor will commission them into his army - the “Phalanx of Alexander,” they will be called.

Caracalla sees their faces as he walks through the lines. He speaks with them, jokes with them, knowing that they are already dead. Their voices are hollow, distant.

He watches his soldiers turn on them, cutting their throats with the speed and efficiency of the greatest war machine in the world. The spurting blood drums and splashes onto the earth, soaking the muddy sand until it cakes the soldiers’ boots and they can hardly move. The killing goes on until every man has been sacrificed.

The emperor awakes. He remembers and smiles. A good dream for a change!

Julia Domna emerges from sleep refreshed. She remembers Caracalla the boy: her precious child. She remembers his curly little head, his huge brown eyes, his tiny fingers and toes. To let him die is unthinkable!

Her mind drifts to another baby—her younger son Geta. He was gentler, sweeter, more contented than his brother. Then Geta’s adult voice shatters her reverie.

“Mother! Mother who bore me! Help! I am being murdered!”

In her mind she sees Caracalla and his centurions bursting into her room in Rome and charging at Geta, their swords drawn. She can hear again the pitiful moans of her younger child as he climbs onto her lap, seeking protection. But she can only watch, and bleed with him when a stray blade strikes her hand.

Julia is fully awake now. She glances at the marble bust of Caracalla across the room. She can see the monster in him. He is proud of his scary looks—delighted to be called “the beast.”

How did it happen, she wonders? How did her sweet son become a menace to mankind? He had enlightened tutors, the best in the empire. She introduced him to the wisest philosophers and sophists; the most profound poets, living and dead. But his father trained him from an early age to prefer the sword and the dark side.

After Geta’s murder in Rome the year after Septimius Severus’ death, twenty thousand people were killed. Many of them were political enemies, many were just in the way—but many of them were offerings, sacrifices to the ambitions of the new emperor.

His soldiers followed orders without question. The emperor was one of them, sharing their food, their hardships, their dangers. He increased their pay by fifty percent and rewarded those closest to him almost daily. His inner circle of officers shared his dream of world conquest—and some of them shared his fascination with black magic and desire for supernatural power. They became a tightly knit coven, bound to each other by their crimes and beliefs.

In Germany and Pergamon, there were mass slaughters like the one in Alexandria. The emperor assembled large numbers of friendly natives under false pretenses, then ordered his troops to strike them down and bury their bodies in pits as offerings to Serapis and the other gods of the Underworld.

Julia shudders as she reviews her son’s hideous legacy. Her pain returns. Again, Geta’s voice is echoing in her mind: “Mother! Mother who bore me! Help! I am being murdered!”

The servants scramble across the mosaic floor, gathering scrolls as quickly as their master drops them. Philostratus has been summoned by the empress. He has been in her company countless times before, but an audience still makes him nervous. What if she asks a question he cannot answer? What if his mind goes blank?

Flavius Philostratus is forty-five years old. His hair is thick and wiry, gray at the fringes; his beard is mostly black, with white patches under his lip and at the corners of his mouth. He often carries his head at an odd angle, as if he is trying to remember something.

A famous sophist, Philostratus is part teacher, part lawyer, and part entertainer, accustomed to public displays of his erudition and intellectual dexterity. But he feels the weight of his reputation as a man with all the answers, especially when performing for the empress, who is his intellectual equal—at least.

He enters her chamber, bows to Julia, and is stunned by her gaunt appearance. She has put her wig back on, but not her make-up. As she speaks, she waves off the servants, who leave her alone with the sage.

“Welcome, Flavius! Thank you for coming on short notice. I have a question or two for you.”

Philostratus is queasy with nerves. Clearly, there is some urgency. Is she dying? Does she want to know the meaning of life? If only he had time to study, to prepare…

“My lady, I am always at your command.”

“Thank you, dear friend. I’ll come straight to the point. What do you think about human sacrifice.”

The blood drains from his face. He doesn’t think anything about it at all. He stammers.

“Do … do you want me to argue for it or against it?”

“I want to know what you think about it. What is your opinion? Can it be a legitimate form of worship?”

“Well, my lady, it must be called a barbaric practice for it occurs among the Scythians, Germans, Gauls, and other uncivilized races. The Phoenicians and Carthaginians practiced it. Athenian youths were sacrificed each year to the Minotaur in Crete before Theseus destroyed it. And, of course, Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia so that the Greek ships could sail to Troy.

“Livy called it the most un-Roman of acts, but pairs of Germans and Gauls were sacrificed in Rome during the war with Hannibal, and the emperor Caligula practiced it before his German campaign. It is said that the emperor Didius Julianus killed a number of boys to discover his chances of defeating your husband, the divine Septimius Severus. The followers of Mithras and Christ are also charged with sacrificing human beings.”

Julia raises her hand for him to stop. “Thank you, Flavius, but is it always evil? What if humans are sacrificed for the common good or in response to a reliable omen?”

Philostratus replies: “Well, Cicero said that the gods can never be appeased by it. It must be deemed evil in all circumstances if it can never please the gods.”

Julia nods slowly. “Speak about Apollonius of Tyana’s views on human sacrifice – if you have read that far in the manuscript I gave you.”

The sophist flushes deep red around his ears. He knew the book would come up - the biography of the famous sage that the empress has commissioned him to write.

“Of course I have read the manuscript, my lady. The book will be completed very soon. I have discovered so much new material. It will be ready within a year—two at the most.”

“Then I will never see it, my friend. Can’t you see that I am dying?”

Philostratus can’t bring himself to respond, so he returns to Apollonius. “Yes, well, the sage was even opposed to animal sacrifice. As you know, he was a vegetarian—he wouldn’t even wear leather shoes.”

“Yes. I was a vegetarian for a while myself, Philostratos. I once tried to get my husband to outlaw animal sacrifice. He said, ‘If I deprive the people of their meat, they will eat me instead.’ And he was right. But cannot the gods be appeased by sacrifice of any kind?”

Philostratus strokes his beard. “Apollonius always prayed: ‘Oh Gods, grant me only what I deserve.’ He said that sacrifices are of no avail because the gods are wise and give people what they need. Divine beings don’t need instruction and they cannot be bought. He said that sacrifice can be of value if it draws one’s mind and body to what is holy, but there must be no blood. According to Apollonius, the sacrifice of a life, human or animal, insults the gods.”

“Thank you, Flavius. Now, what can you say about killing a member of one’s own family—is that ever justified?”

Again, Philostratus is surprised by the question. What has the empress been reading?

“Of course, there are many examples of this. Romulus killed Remus, Cain killed Abel, Medea killed her own sons, Heracles his children, Oedipus his father.”

Julia interrupts. “In each case, there was a different reason. Jealousy, revenge, madness, ignorance. But what if there is no desire to do it, no hatred or personal gain involved. Can it be one’s duty to kill a parent or a sibling or even one’s child? What if the good of others demands it; what if one is related to a monster?”

Philostratos considers. “In Roman tradition, the head of the family has the right to kill any of his children or his slaves. Recently, the German women of the Chatti and Alemanni killed their own children to save them from slavery. Antonia starved her wicked daughter Livilla to death. The empress Domitia conspired in the death of her husband Domitian for the good of the empire. Many regret that the divine Marcus Aurelius did not put away his son Commodus.

“It has been said that a family member is part of oneself. If one has a gangrenous limb, one has it removed. Otherwise it will poison the whole body.”

Julia nods, satisfied for now. “Thank you my friend. That is all.”

She rings a small brass bell. A servant immediately appears, hands a bag of gold coins to Philostratus, and leads him away.

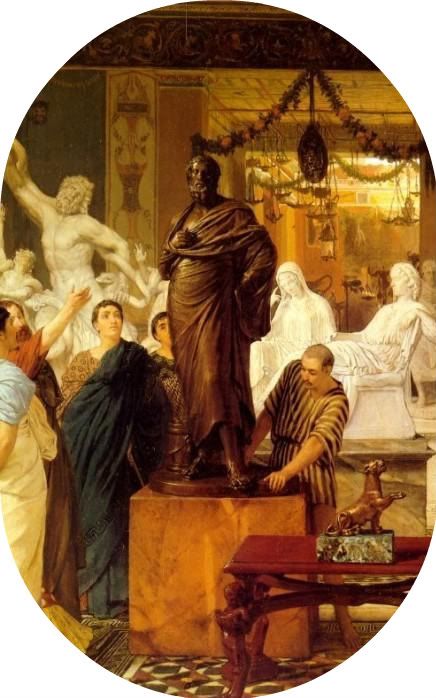

But Julia is still looking for a reason to spare her son; to believe that he can become a better man. She orders her litter bearers to take her to see Callistos, the greatest sculptor of his time. His workshop was moved from Rome to Antioch when Caracalla came east two years ago.

Callistos is renowned for the psychological insight and power of his portraits – especially of Caracalla and of Julia Domna. So life-like and awe-inspiring are his works that he is believed to possess supernatural powers – he believes so himself.

Summoning Callistos to the palace is no longer done. His visits there were always disasters. He was unable to hide his contempt for the courtiers or his exasperation at being pulled away from his work, which he considers far more important than ruling the world.

The sculptor’s studio is like a small fortress. It is guarded by a legion of black mongrel dogs: gangly beasts with long thin legs, smeared with white marble dust from the workshop floor. The compound is surrounded by a makeshift fence – ostensibly to keep the dogs in, but actually intended to keep intruders out. The gate is augmented by an assortment of loose bars and screens and other contraptions to prevent the dogs from leaping over or squeezing through. But this frustrates visitors even more than the dogs, for they must disassemble and reassemble the arrangement every time they pass through.

The master, like his animals, is covered with white dust. His shocks of beard and hair and chest fur are laden with powder, making him appear old and withered. Only his large, bright brown eyes reveal that he is still a young man.

Julia and her bodyguard enter the studio. The master is working on a colossal statue of Hercules. In the corners of the room are numerous statues and busts in various stages of completion, some of them stark white stone, others already brightly painted. Several apprentices steal peeks at the empress, but know better than to stop work when the master is around.

Callistos tries to greet the empress with proper respect and attentiveness – but he can’t quite pull himself or his mind away from his work. Julia is used to this; she has learned to content herself with occasional bursts of responsiveness as he carves and caresses the stone.

“I have come because I am dying and I want to discern my son’s future before I leave.”

The sculptor glances at her briefly and grunts.

Julia continues: “I believe that you know him as well as anyone. Your portraits reveal traits that even his mother didn’t recognize.”

“I only carve what I see—his features may be read by anyone.”

“Come now, Callistos, I know better than that. You can see into his soul. You found parts of his nature that he couldn’t express and showed him how to reveal them. He has modeled himself after your sculptures, not the other way around.”

The sculptor looks at the empress with alarm. She reassures him.

“You can be frank with me. I am here because I want to know what you see in him. All of it. Do you see potential for goodness as well as the monster?”

Callistos begins to flail at the marble with hammer and chisel, flinging out his words with equal ferocity.

“He has an animal spirit. Rage. Hatred. Fear. Destruction.”

Each word is driven home with a hammer blow. He pauses – holding the hammer above his shoulder.

“Goodness? No. It is gone. He gave it all to his brother and then he put it to death. He believes it is his duty – his destiny - to terrify. He has become the monster.”

He looks directly at the empress and points at a bust of Caracalla behind her. She turns and confronts her son’s ferocious glare, captured in stone. She trembles. Callistos presses his lips together and resumes his hammering in earnest.

The conversation is over, but Julia decides not to notice. She speaks to Callistos as if he were still listening, knowing that he is not.

“I have been surrounded by death my whole adult life. My husband killed hundreds of thousands of people, for so many reasons—some good, some bad. My son has continued the killing, for worse reasons.

“But I have never killed a living soul. I have stood by and watched it happen. Perhaps I should have intervened more often than I did. But I have never intentionally let another man die. And now I must – and it is my own son. It has to be done, for the sake of so many innocent souls. May the gods forgive me!”

* * *

Caracalla has time on his hands, waiting for the army to assemble for the march from Edessa to Carrhae. He has heard there is an Egyptian soothsayer in Edessa, a man named Serapio, so he summons him for amusement.

The Egyptian is a small, very slight man with a shaved head and grayish skin. He has a fixed grin on his face and doesn’t seem particularly nervous in the emperor’s presence, despite Caracalla’s frowns and grimaces. This irritates the emperor.

“So, you claim to see into the future?”

Serapio smiles and answers: “Like a fisherman throwing his net into the sea, I cast my mind forward—but I don’t always catch a fish.”

“What do you see in my future?”

Serapio looks at the soldiers preparing for their journey and laughs gently. “You are going to leave Edessa, Caesar.”

Caesar is not amused. “Don’t waste my time, soothsayer. Tell me something I don’t know or I’ll have you punished.”

Serapio doesn’t hesitate: “Caesar will not live much longer – this journey will be your last.”

Caracalla growls. “So, you are angry with me. What else will you dare to say?”

“That you will be succeeded on the throne by an African, and very soon.”

Caracalla looks at Macrinus, his prefect and second in command. Macrinus is from Mauretania in northwestern Africa.

“I suppose you mean Macrinus here, is that right?”

Serapio looks directly at the emperor. “As you say.”

Caracalla stomps about, wrestling with the prophet’s words. He looks at Macrinus, who trembles slightly.

“No!” barks Caracalla. “This is nonsense. You are only trying to frighten me. You have performed no rituals, consulted no oracles. I do not believe you!”

He motions to a centurion. “Seize this man! I will teach him to toy with me.”

At that moment, a wagon is passing by carrying a caged lion. Caracalla stops it and has the lion released into a stockyard nearby. He tells the centurion to throw Serapio in with the beast.

“Now what do you predict your own future will be, Serapio? Will you be the lion’s lunch or its dinner?”

The gathering soldiers laugh and begin to ooh and aah as the lion moves menacingly toward the Egyptian. But Serapio sits on the ground and appears unperturbed. When the lion comes close, he holds out his hand and the lion licks it, then sits passively beside him like a housecat.

Caracalla is enraged. He orders for the lion to be returned to its cage and tells the centurion to execute Serapio at once. “I’d like to see you make the centurion lick your hand, magician!”

Serapio answers calmly. “If this had happened tomorrow, I could have done so. Then the spirits would have protected me. But today is not tomorrow, so I will die. Watch how it is done, Caesar—your turn will come very soon.”

The centurion dispatches Serapio with a blow to the back of his head using the butt of his sword. The seer crumples to the ground dead, but with a smile still on his face.

Postumus, the young messenger from Rome, is luxuriating in the baths, still recovering from the hardships of his journey. It has only been a day, but already he is anxious to mount his horse again, especially if it means seeing the emperor in person.

A heavyset praetorian guardsman circles the pool and summons him from the water. “The lady Maesa has a mission for you. You are to take some messages to the emperor’s staff. You will leave in the morning.”

When Postumus sees Maesa, he is surprised by the great lady’s age, especially after having seen her sister. Maesa’s jowls sag and there are heavy bags under her tired eyes. Her tone is one of urgency, but her words are strangely incongruent. She hands him a leather pouch bearing her personal seal.

“In here are several letters for the emperor’s lieutenant, the praetorian prefect, Marcus Opellius Macrinus. They are routine, not very important. Give them to Macrinus and to no one else, do you understand! He will know what to do with them.”

Postumus is disappointed. He wants to meet the emperor.

Marcus Opellius Macrinus looks like a lawyer. His furrowed brow and cheeks and rubbery lips make him seem severe, even in his sleep. Happiness, fear, despair, mirth - all look the same on his face. Even his single earring does nothing to soften his appearance. Despite many attempts to fit him, his cuirass always looks too large, as if his bony arms and legs were tacked onto someone else’s torso.

He feels out of place with the army - a stork among eagles. But as one of the two prefects of the Praetorian Guard, he must deal with the soldiers.

Today, it is an appeal. His client and fellow countryman, Julius Martialis, wants help in obtaining a promotion. A few days previously, Martialis’ brother, also a soldier, had angered the emperor and been executed. Julius fears that this will ruin his chances for advancement.

“Sir, I have served you with all my heart for seven years now. I believe that I have been useful to you, and I have always spoken well of you to my fellow soldiers. I ask only that you will grant me the rank of centurion, which I have earned, and the honor of continuing in your service.”

Macrinus fiddles with his beard. “The emperor may not approve of your promotion so soon after your brother’s offense. I know that you are innocent, Martialis, but you must wait.”

Martialis is clearly angry and distressed over the loss of his brother. He struggles to remain composed. His voice is unsteady.

“Now that my brother is dead, it falls upon me to support his family as well as my own. I cannot do this without the promotion that I am entitled to. Please intervene with the emperor, sir! Assure him of my loyalty, that I do not bear a grudge...”

Macrinus interrupts, “But you do bear a grudge - I can see that. Cool off for a few months, Martialis. Let things settle down. Then I will approach the emperor.”

Suddenly, Caracalla bursts into the tent. Macrinus rises from his chair and salutes him. Martialis snaps to attention. The emperor gestures for them to be at ease.

“Macrinus, when we enter Carrhae, I want everything to go smoothly. Have the people been informed of my recruitment plans?”

“Yes, Caesar. All is in readiness. The citizens are preparing a celebration in your honor. The entire city will turn out to welcome you. I have made arrangements for a feast.”

“Good! I want everyone to be in a good mood and well fed. Then I will summon the young men to gather in the gymnasium.”

Caracalla glances at Martialis and asks, “What does this man want?”

Macrinus replies, “He has requested a promotion to the rank of centurion, Caesar. I have explained to him that it is too soon after his brother’s disgrace.”

Caracalla frowns. “It will always be too soon. I can never trust the brother of such a scoundrel!”

He turns and addresses Martialis: “You are fortunate that I didn’t have you executed as well. You are just like your brother—a coward of low birth, loyal to Macrinus and not to me. No, promotion is out of the question!”

Caracalla turns to Macrinus. “When we get to Carrhae, find Martialis a post in the garrison there. I don’t want him with me when I’m fighting Parthians.”

* * *

On the following evening, the 8th of April, the army prepares to enter Carrhae. Caracalla’s chariot awaits him, decorated with gold and ivory and drawn by four white horses. Some distance away, Macrinus is adjusting and readjusting his cuirass as a horseman approaches.

“It’s a courier from Antioch,” says a soldier.

It is Postumus, completing his long journey from Rome. He sees the emperor’s chariot in the distance and wants to ride to him, but the guards lead his horse to Macrinus.

“I have a message for the emperor! I have been told it is urgent.”

“Let me see,” replies Macrinus. “That is the empress’s sister’s seal. Nothing urgent. I will deal with it later.”

Postumus is crestfallen: “No! Wait! Your honor, please! There has been a mistake. One of the messages comes from Rome. I was told by Flavius Maternianus himself that it is extremely urgent and for the emperor’s eyes only. His life may depend on it.”

Macrinus is preoccupied with the coming events. “Oh, very well. I am joining the emperor now anyway. Come with me.”

Caracalla is clearly in a bad mood. He is fussing with his armor and adjusting his wig. Finally, he tosses his cuirass aside. “It is too hot—I will put it on when we reach the city.”

Alexander the Great visited Carrhae five hundred and fifty years before—Caracalla wants his entry to be just as grand and impressive. But the emperor has eaten too well the past few days, in celebration of his 29th birthday on April 4th. All morning, he has struggled with wind and diarrhea. As Macrinus approaches him, Caracalla sees the wide-eyed courier at his side.

“Who is this?”

Postumus dismounts and wobbles to one knee. “Hail Caesar! I have come from Rome and Antioch with urgent messages for your majesty.”

Caracalla looks at the leather pouch and its seal and then at Macrinus. “Looks like routine letters. You deal with them.”

“Yes, Caesar,” says Macrinus. Postumus no longer cares – he has had his moment, basking in the imperial sun.

Finally, Caracalla mounts his chariot and the procession moves forward, but Macrinus lags behind on foot. His secretary attends him as he unrolls the scroll from Rome. As he reads the words, his shoulders tighten and fear pierces his heart.

“…The African sage Nomenius has predicted that the prefect Marcus Opellius Macrinus will succeed you as emperor... He says that Macrinus is already plotting your murder. Caesar; you must look to your safety!”

Macrinus stops walking. Panic tries to seize him, but he resists. Ever the lawyer, he searches for a loophole. Coming so soon after Serapio’s prediction - and from the emperor’s close friend Maternianius - this will be taken very seriously. The emperor’s first impulse will be to kill Macrinus and all of his family.

The prefect resumes walking, weighing his options: “If I kill Caracalla before he kills me, the army will revolt. They will tear me into pieces and feed me to the dogs. If I try to arrange his death, whom can I trust? And I would still be a suspect, second in command, the one with the most to gain. The soldiers would want to blame me and take revenge.”

Gradually, Macrinus becomes clear about what to do. He motions for a horse and rides to catch up with the emperor.

“Your highness, I have grave news that must be addressed immediately. I beg you to stop.”

Caracalla, still feeling ill, is grateful for a pause. Nevertheless, he pretends to be annoyed.

“Was Alexander distracted by business on such a day? You have no respect for the importance of what is happening here, Macrinus!”

He reins in the horses and climbs out of his chariot.

“Forgive me, Caesar, but this is vital. I have received word from Rome, from Flavius Maternianus. The African seer Nomenius has predicted that I will succeed you as emperor. He claims that I am plotting against you.

“I am mortified, Caesar! I swear it is not true! To outlive you would break my heart and I have no desire to rule. But Nomenius is a great prophet, and I do not take his predictions lightly. Therefore, I offer my life to you now. Kill me, so that you may live and the empire may prosper!”

Just like that, Julia Domna’s hopes and fears have come to nothing. And nothing stands now between Caracalla and the unsuspecting youths of Carrhae.

Macrinus falls to one knee and bows his head. Caracalla takes the scroll from his outstretched hand and reads it. The emperor rubs his chin and hesitates. His instinct tells him to believe the prophecy, but he is counting on Macrinus to keep order in the eastern provinces while he conquers Asia.

“If you were disloyal to me, then you would have kept this to yourself until you found a way to strike first. No! I will not execute you. Perhaps the prophecy was intended to show me who my friends really are? Arise, Macrinus! You have been spared again!”

Macrinus has calculated correctly. He staggers to his feet.

Caracalla looks at the sky. “It is getting late—we will enter the city tomorrow. I think I will spend the evening at the Temple of Lunus, the moon god. It is not far from here. Come with me, Macrinus. You can sacrifice to my clemency! Bring along my Germans and Scythians and a cohort of praetorians.”

As the rest of the army sets up camp beside the road, the emperor’s party prepares to leave for the temple, just a couple of miles outside of the city. As Caracalla moves to mount his horse, there is a muffled noise and an awful smell. The emperor blushes.

“Give me a moment, Macrinus. My stomach troubles me this evening.”

Macrinus signals for the troops to stand at ease. The foot soldiers break formation as their officers dismount. Caracalla climbs a small rise nearby, signaling to his guard to give him privacy. He crouches down behind a boulder as the soldiers look away.

Suddenly Martialis strides past Macrinus towards the emperor, carrying a flask of water and cupping his ear as if he has been summoned by Caracalla.

Martialis’s upper lip and nose are cold and throbbing—he can hear his own heart beating. As he nears Caracalla from behind, he drops the flask and pulls out his dagger.

Macrinus gasps as she sees Martialis thrust it into the emperor’s back, just below the left clavicle. Caracalla slumps forward, dead as the blade finds the back of his heart.

Martialis immediately turns and strides back down the hill as if nothing has happened. The few soldiers who saw are paralyzed, still not fully comprehending. Martialis begins to run toward a horse, neglecting to drop the dagger. A Scythian bodyguard sees the blood dripping from its blade and understands. He throws his javelin at Martialis—it pierces his neck, killing him instantly.

Neither the ruler of the world nor his lowly assassin has made a sound. Very gradually, a groan begins to rise from the soldiers as they realize that the world has changed.

* * *

A dusty contingent of praetorians clatters through the palace to Julia Domna’s chamber. The officer in front carries a golden urn, the size of a winnowing basket. The empress knows its contents—her son’s ashes—but she imagines that it holds the body of her baby. She imagines his plump, lifeless body stuffed into the metal bowl.

Julia strikes herself viciously on her breast. The pain is excruciating, but she welcomes it. She weeps for both her sons. Her tears are wrung from the innermost fibers of her being. She feels that when they are spent, there will be nothing left of her.

There is a letter from Macrinus. He explains that a disgruntled soldier has stabbed her son to death – acting alone. Julia doesn’t care if it is true or not; it was necessary. Macrinus tells her she may keep her position, even her detachment of the Guard. He offers to work together with her in ruling the empire. He even hints at marriage, if she would consider it.

After Caracalla’s death, Julia Domna’s life seems unreal. Her sense of duty keeps her mind from drifting away, but nothing can keep her body whole. The cancer has its way.

One morning at sunrise, only weeks after her son’s death, she lies on a couch in her chamber. She feels as if her body is an oil lamp—her life-force the fuel and her heart the wick. It burns so gently, so sweetly, and then it carries her away like smoke.

The assassination of the Roman emperor Caracalla occurred in A. D. 217. The story is told by the contemporary historians Cassius Dio and Herodian. Dio tells us that Caracalla was murdered when the message warning him about Macrinus was held up at his mother’s headquarters for routine screening. He states that a similar letter was sent directly to Macrinus, arriving first. Herodian claims that the letter was among several sent to Caracalla, but that he was preoccupied when they arrived and told Macrinus to deal with them. There is no historical evidence that Julia Domna attempted to be an accessory to her son’s murder. The names “Callistos,” “Nomenius,” and “Postumus” have been given to real people whose names are unknown.

Jasper Burns was born in Virginia in the mid-20th Century. He has been writing and illustrating books about the past since childhood. He is especially interested in the very old - prehistoric life and ancient history. Publications include five books about fossils and fossil collecting, a book of biographies of the Roman empresses, and a novel about the Roman emperor Tiberius and his first wife Vipsania. However, his latest project is a science fiction novel set in the not-too-distant future. His drawings and writings may be seen at his website.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

While doing research for my nonfiction writings, I often stumble upon coincidences and ambiguities that suggest untold stories or alternative views of historical events and circumstances. If there is enough evidence, a historical theory may develop. Or my imagination may begin to spin a yarn that is unproveable. In either case, writing historical fiction is the best way to explore the possibilities and share them with others.

0 comments:

Post a Comment