The Greatest Pianist in the World

by Marko Fong

1 : Prelude and Verse

For forty years, before a Vladimir Horowitz concert tour, a crane appeared outside the pianist’s Fifth Avenue apartment. Workmen would load the thousand pound black Steinway Concert D onto the crane to float from the maestro's sixth story practice studio to sidewalk. Horowitz was notorious for canceling concerts unless his personal instrument was available and tuned to his specification. He often happily played another piano in the actual concert.

He even had a personal tuner who traveled with him to set the octave intervals just a little wide and forgiving with the A above middle C tuned slightly flat at 436 cycles per second for solo recitals. When playing with orchestra, Horowitz insisted on 444 to make the piano sound brighter and faster than the string section's usual 440, which made the string section sound less competent than the soloist. This was unless he was playing for Fritz Reiner who would personally take a tuning fork to the piano five minutes before concert time. As a gesture of respect, Horowitz also consented to let his father in law Toscanini articulate the piano's tuning settings with the rest of the orchestra. Of course, Horowitz only played with Toscanini before he became enough of a star to demand billing above the conductor.

When the crane appeared, a crowd would gather to watch the eleven foot long box of stressed mahogany and steel wire strings journey to street level. "Horowitz's piano" they whispered to one another.

Once the instrument touched sidewalk, the onlookers observed an unspoken fifteen foot perimeter from the instrument as if mortals, even New York mortals, had no right to interfere with the master's microphone to heaven.

It was expected that a virtuoso as great as Horowitz would possess an artist's temperament. Horowitz's practice studio always bore the faintest smell of the freshest filet of sole to be found in Manhattan. Wanda Horowitz made certain that her husband got his favorite lunch within seven minutes of twelve thirty either on the balcony adjacent to the practice studio. If she didn't, the pianist brooded for days.

I remember two other items from Horowitz's practice studio. The first was a dark velvet cloth that the maestro used to wipe his keyboard before playing. No other hands could touch his keys unless the ivories were cleaned thoroughly in between. I saw the maestro forget his own fetish twice.

The second was an Ampex reel to reel tape recorder. Horowitz listened to his own concerts and practice sessions repeatedly. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that he never learned to operate the machine. He was the same man who took his first big check from an American tour producer in 1936 and used it to buy a brand new Studebaker sedan for five thousand dollars, despite the fact that he didn't know how to drive and never learned. Wanda hired a chauffeur so that they could get some use from their purchase. For many years, Columbia records supplied an intern who took on the job of cueing and replacing the reels four times a week. In the absence of the intern, Mrs. Horowitz would inveigle the chauffeur, butler, or in an emergency even the superintendent. The couple never had luck keeping servants.

For close to two years, the task of tending to the maestro's tape recorder fell to me. Before it was added to my duties, I had the opportunity to watch Wanda make her tape recorder requests to others. As she walked them through cueing, changing reels, setting levels, and even splicing damaged tape on the 32 inch per second Ampex, it became clear that Wanda knew perfectly well how to operate the machine. She simply hid it from a husband who never noticed. Little in their marriage was as it appeared.

Why am I telling this now? For the first twenty five years, the reason to keep quiet was simple enough. I signed a non-disclosure agreement drafted by a deaf-Brooklyn attorney hired because he literally had no connection to music. In 1951 when I took the job, six hundred dollars a month was a lot of money for part-time work that didn't interfere with my piano studies at Juilliard. Now, I am eighty years old.

My music bio consists of one ASCAP credit, a piece called “Blues for Sonya” that was recorded then disappeared. Six years ago, arthritis took away my capacity to play the piano. I failed to make it in any significant way as a musician. This may be the only thing I contribute to the music world .

I was first tempted to break the secret in 1979. Horowitz was celebrating the 60th year of his career as a soloist and was slated to return to play in Moscow for the first time since 1919. A popular TV news magazine did a segment on the Horowitzes. At this point, Horowitz's detractors had disappeared and the word "legendary" appeared in all his liner notes. His concerts now sold out weeks before the announcement appeared in the paper. The show's anchor played straight man to a comic Wanda as she walked them her regimen of supporting her husband-diva. As the zoomed in on the fresh squeezed orange juice served at 9:45 AM, the anchor delivered the setup line, "What if he gets a few seeds in the juice?"

The tiny Wanda gave a practiced theatrical stare and deadpanned. "If he complains, I throw it at him."

"So who's the real boss of this marriage then?"

"I am the managing partner. He just plays piano a few hours a day. A good life, you think?"

The camera cut to Horowitz practicing then a montage of the couple walking in their garden at their Connecticut home, Wanda dressing him for a concert, and the two sitting and laughing as they traded barbs and charm with the anchorman.

One would never guess the real nature of the marriage. In their contract with the network owned by the same corporation as Horowitz’s record company, the couple insisted on conditions. The forbidden topics began with Horowitz's homosexuality, their daughter Sonya's suicide in 1974, and went on for two pages.

The show, which then had a reputation for investigative journalism, did ask one probing question. "Maestro. They say you never left this apartment for twelve years from 1954 to 1966. Tell us about that."

Horowitz's answer did not stray from the one Wanda had coached him to give for the camera: "It's a really beautiful apartment. Why would anyone want to leave such a place?"

I didn't think the world needs to know that the maestro went into treatment in 1951 to have his homosexuality eliminated or that he underwent electroshock treatments for depression in the early sixties. People don't need to know that Wanda rarely spoke to her husband for seventeen years even as she prepared his lunches, dealt with tailors, managed their social schedule, and coached him on how to present himself to his public. Still, the world should know what happened to make the world's greatest pianist quit performing for so long.

I wanted to come forward, but even as late as 1979 I still imagined that the Horowitzes might help me get a teaching position at Juilliard or a job running rehearsals at Columbia records. I was still deluded about my real prospects in music. After that, I gave little thought to the secret for some twenty five years.

A few weeks ago, my niece came to my assisted living facility and brought me a DVD of that 1979-news-magazine segment. "It's Horowitz, Uncle, the greatest pianist in the world…You said you knew him."

The show kept calling the maestro, "Russian" and the concert in Moscow a return home. One of the oddities of Horowitz's life is that he was Ukrainian. It just happened that his career coincided almost exactly with the Soviet Union. He gave his first concert at 17 in 1919 (the official year of his birth was 1904 because his parents lied to keep him from being conscripted). The Ukraine was a separate country from then. It regained sovereignty in 1991. Horowitz died the year the Berlin wall came down, 1989. Horowitz was from Kiev. He had lived outside the Soviet Union after 1929 for a simple reason. For a Ukrainian Jew in the Soviet Union, pogrom and purge were much bigger P's than pianist.

My thumb is stiff and I struggle to find the pause button on the remote of the DVD player. I repeat the words to myself, “I am the holder of Horowitz’s secret.”

Here’s the simple version. From 1951 to 1953, it was my job to keep the fact that the world's greatest pianist was taking piano lessons a secret from the world. If you know classical music, you would know that it is not unusual for well-established musicians to continue lessons with a mentor or coach. There wasn't any shame in taking lessons even for Horowitz. What made them different was that he was taught by a man whose only formal studies took place at the Ohio School for the Blind. Horowitz’s teacher had performed only once in his life in a public concert hall recital and that opportunity had only been the result of Wanda calling in a favor. The rest of the time, he had made the bulk of his living by playing in bars on mistuned pianos. In 1951, jazz musicians knew who Art Tatum was but hardly anyone walking down 5th Avenue would have recognized that the black man walking into the Horowitzes’ apartment house was anything but a delivery boy.

Part 2 : Choruses

Some biographers have documented that there was something of a respectful friendship between the world's greatest classical and jazz pianists. One famous story claims that Horowitz, so impressed with one of Tatum's versions of the song “Tea for Two”, transcribed it and played it for the jazz master during to show that he too could play what Tatum had played. Legend has it that Tatum responded by sitting down and improvising yet another even more dazzling version of “Tea for Two” then announcing, "You can copy it, but it doesn't matter until you understand it."

In another story, Horowitz and Stokowski both visited Jimmy's Chicken Shack, where Tatum had a regular gig in Harlem, and Stokowski allegedly told Horowitz in front of witnesses "That man is the greatest pianist in the world."

I had ties to both men. Horowitz had once visited my performance class at Juilliard in 1946. I was in my early twenties, straight from Gaudalcanal and the GI Bill, eager to resume my efforts towards a performance career. I was also good looking. When Horowitz showed an interest in my playing that day, my musician's ego was blind to other motives. Obviously, he wouldn't pretend with a complete clunker of a pianist, but I was naïve enough to tell myself that his interest was musical.

He came to my recital once. He took me to lunch on two occasions. One time while I executed a chromatic run in Beethoven's Diabelli variations, he began showing me how not to arch my hand by stroking it ever so lightly. Nothing was said, I simply didn't respond. I may have tightened ever so perceptibly. I'm pretty sure Horowitz had ferreted out the fact that I was also gay in the way that those of us who are detect and send clues. This may have made my rejection of him even worse. His invitations and interest in my performing stopped.

In 1947, I took a part-time bartending job at Jimmy's Chicken Shack. At this point, I had figured out that my future as a classical soloist had limited prospects. I was fascinated by jazz, especially the controversial-emerging form called Bop. A few years earlier, Charlie Parker washed dishes here and had listened to Tatum play two nights a week. Jimmy's thought that having a white bartender gave the place respectability. As the bartender, especially as a bartender who didn't mind pouring the better stuff for the help, I got to know Art Tatum or Art got to know me quickly.

It was easy to understand why Tatum drank so much. He was a mostly blind black man who happened to be a genius on the most classical of instruments, the piano. He played with a speed and technique that matched any classical soloist. In order to play, he had to live on the road where he fought with club managers who tried to cut his share of the house, endured bad hotels, and suffered nasty patrons. His one joy was playing after hours well into morning and drinking as he played. In general it was two fifths a night interspersed with an occasional stein of beer and a cocktail or two. The drinking never seemed to affect Tatum's playing, just his health. Even in 1947, the uremia was beginning to affect him. Although still working, Tatum couldn't tour and because of the ASCAP strike he couldn't record. He didn't record in a studio from 1945 until 1953. Essentially, the world's greatest jazz piano player was supporting himself as a cocktail pianist.

Even musically, Tatum was being left behind. He was a two-handed jazz pianist who played solo at a time when all the talk was about Bird and the new thing. He might have inspired Bird, but most hipsters would tell you that Tatum was too old school, a swing guy who just happened to play faster and more adventurously harmonically than anyone else. Even in 1947, the one-handed style with the bass and drums taking over the rhythm while the piano player played fleet single-note-horn-like lines like a horn was taking hold, because no one could follow Tatum anyway.

One night after one AM, Horowitz and Wanda walked into Jimmy’s Chicken Shack. The two must have come from a society party uptown. He wore a tux, mirror black shoes, and a top hat. Wanda was in an evening gown. They couldn't have looked more conspicuous. Nonetheless, the couple took a table in the back and ordered two glasses of champagne.

Art was playing Ellington's “Caravan”, a fast piece that relies on a middle eastern riff and a rhythm that openly imitates a beating drum. In the second chorus, Art had turned it into a sly rhumba, quoted from three or four other songs, then dropped straight back into the groove by switching from minor to major while interpolating the “Beer Barrel Polka.” With anyone else, it might have seemed gimmicky once you got past the sheer amazement. With Tatum it was sublime and seemingly endless. By chorus five, the customers were hooting, "Go Art…" "Whoo…" "Swing it man."

They had barely noticed Horowitz in their midst. Just as Tatum hit the tonic and dropped his Caravan just short of some Parisian Thoroughfare, a guy, clearly drunk, yelled from the back, "Hey Art, how about the Stars and Stripes Forever?"

I looked closely at the Horowitzes. Art could not have seen the formally-dressed couple in the back and no one from the club had had a chance to let Art know. Art was surprisingly good about requests. I heard him play “Melancholy Baby” three times and had heard him play Andrews Sisters' songs on at least half a dozen occasions particularly when there was a tip involved. I think he drew the line at Jimmy Durante, but I couldn't swear to it.

This is the deal. In 1944, Horowitz had played at Carnegie to celebrate his American citizenship. Ever the showman, after two hours of Chopin, Rachmaninoff, and Schumann, the maestro came out and did an encore of variations on the “Stars and Stripes Forever.” With the war still on, the reaction was thunderous. A 78 of Horowitz's version even made the charts.

Art started straight with Sousa's melody and a firmly established march tempo in the left hand. In fact, it sounded like he purposely wasn't going to show off at all. When Art was on there would generally be silence, I started to hear the clink of glasses and murmured conversation as Art hit the bridge a third time. I hadn't noticed, but Art's rendition subtly shifted from march to blues and suddenly the Stars and Stripes, the ultimate martial music, had transformed into a spiritual, but the fastest spiritual ever. I had always been amazed by Tatum's playing, but this was composition. It was deep, stunningly beautiful, a meditation on being black, patriotic, suffering, and proud all at once. The audience went silent. Horowitz sat there his head down. I saw him wipe away a tear with his napkin. At the end, the house didn't even have the presence to applaud. They just sat in mute worship.

The Horowitzes came back three times in two weeks and each time Vladimir and Wanda invited Art to join them for drinks. I had kept a careful distance from the Horowitzes. I paid respects. He would greet me by name, but we did not speak beyond that. It seemed that this was going to be the way we would deal with mutual awkwardness.

It was Wanda Horowitz who asked me to meet her for lunch at Tavern on the Green. "I have a job for you," she announced after the preliminaries but before the clam chowder.

I would have five basic responsibilities. I had to get Tatum from his room in Harlem three times a month to Fifth Avenue. I had to make sure that Art never told anyone else. I would get the thousand dollars a lesson to Art. I had to keep anyone from ever noticing our regular visits. During the lessons, I was to see that Art always had a full bottle of scotch available. In addition, Art was going to get a concert in a music auditorium with a program. It seemed that Wanda also said something about helping my career.

For thirty seven visits, Art Tatum and I dressed up as piano tuners. On a couple occasions, Wanda even arranged for us to tune the Baldwins and Steinways of residents in the building. Art could tell you just which keys were off by playing a couple scales.

Part 3 : Scherzo and Cadenza

Art and Vladimir concentrated on a single song, “Tea for Two.” Horowitz would usually play first. Most would wonder why the loudest-fastest-classical pianist in the world would even consider the possibility of lessons. Horowitz’s “Tea for Two” was filled with arpeggios, quadruple speed sections, counter melodies, and dazzle. Art always sat next to the piano, poured himself a glass, and would shake his head, "That's nice, but it still doesn't swing."

The first few times, Horowitz had this puzzled look. "I am not a jazz player. Why must it swing? I am improvising, yes?"

"All music that's worth listening to has to swing."

Art would motion for Vladimir to move aside and Art would play sixteen bars of “Tea for Two” or was it “Tea for Two Hundred and Twenty Two?”

One time when Art was playing, he caught Horowitz tapping his foot.

"What you doing there man?"

"Doing vere?"

"I might be blind, but I hear you tapping."

Art had this huge laugh when he was genuinely in a good mood. He had enormous hands that he used to gesture when he talked. "So you do know what swing is, then?"

"Yah, I guess."

Horowitz couldn't hide his smile.

"Okay, then. You show me."

Horowitz might have known what it was, but he couldn't quite do it. I did, however, notice one other thing. Horowitz forgot to wipe down the keys after Art played.

Sometimes, the two talked through the lesson. Once between choruses, Horowitz, never especially tactful particularly without Wanda, said, "You have no idea how difficult it is to be a Jew in Europe. You Americans don't understand the suffering."

Art wasn't an arguer. He slipped over to the piano bench and played two quick choruses of the blues. I'm not sure that Horowitz caught the joke. Like Art, his hands sometimes seemed bigger than his body. Instead of saying anything, he raised them as if to play fortissimo then went back to Tea for Two, one of his better versions, but it still didn’t swing.

Horowitz would show Art antique desks, give him tastes of vintage cognacs, and let him feel the material of his perfectly-tailored suits. One day, Horowitz was showing off a diamond ring bought from a single royalty check and Art joked, "Maybe you should be the one giving me piano lessons."

Horowitz’s answer with a riff from one of his radio interviews, "America has been so good to me just for being able to play the piano. I came as a refugee and this is the kindest nation in the world."

I only wish that Art Tatum had responded by playing the blues that day. Some moments are subtle but portend huge changes. Not long after Horowitz said that, the saddest thing in the world happened.

Tatum hadn't recorded in six years at that point. Even though Wanda had gotten him a concert in what she called a "proper hall", little had come of it. The Times and the Herald chose not to review. To be honest, Art's music always sounded better when there was a bottle on top of the piano. I was still bartending at Jimmy's and Art was still playing there. I don't know if anyone else noticed, but Art's playing in public began to change.

He was still fast, the harmonies were still dizzymaking, yet something about Art was gone. It was getting just a little bit predictable, as if he were playing from arrangements instead of improvising or creating at the keyboard. He was playing more like Horowitz.

By contrast, Horowitz's playing took on a looser quality. He sounded fresher in concert than ever before. Various critics attributed it to health regimens, a new seriousness about musicianship over showmanship, competition with Rubenstein. One critic wrote,

Horowitz has always been the great soloist in the romantic tradition. He plays to the hall, sometimes takes liberties from the score in the tradition of Liszt and Hoffman. Some now insist that the musician's job is to interpret the composer's intentions. The romantic understands the composer's intention.

Last week, the Russian unleashed a fresh phase of his career in a program that included Scriabin, Liszt, and Horowitz's own spectacularly inventive transcription of Bizet's Carmen. Where Horowitz once seemed mechanical and merely showy, he has now become a serious interpreter…

As Horowitz's public playing flourished, Art’s began to falter. It was as if the Eastern European were a musical vampire. Even odder, Horowitz never quite learned to swing “Tea for Two.”

Art remained the gentle teacher and when he played during the lessons, his little asides were as feeling and inventive as ever. The biographers say that Art's uremia got even worse around this time. His fingers were stiffening. Every now and then I could see the signs that he would shorten runs or hit a double note that he couldn't instantly resolve harmonically.

Part IV : Finale

In 1953, Art got a call from Norman Granz to come to Los Angeles to record. Granz, a Jewish attorney from Brooklyn, had a special talent for promoting jazz musicians. He was the first impresario to get jazz musicians big money to play in concert hall venues. Granz encouraged his stars to play to the crowd, encouraging them to play faster,louder after playing written melody at least once. He packed his concerts with sax players like Illinois Jacquet who hit the high squealy notes and Oscar Peterson, a Canadian who idolized Art and who played uncommonly fast and complex even if it was neither particularly original nor surprising. Art took the first train to Los Angeles and Granz recorded him for forty two hours. Art never saw Horowitz again nor did I.

On his way to California, Art stopped in Toledo to visit his son and first wife. He was never especially close to Art Junior, but he bought him a piano and set aside five thousand dollars for him to go to school or buy a house. No one knew how Art happened to be so flush.

The resulting recordings with Granz, though still wonderful, aren't the real Tatum. Some insist that the drinking had caught up with him. Others insist that he'd just lost it at age 45. Tatum was dead by 1956 from kidney complications. It remains the only extended set of studio recordings of Tatum’s playing after 1945. In the mid-70's someone tracked down an air check of Tatum playing after hours in the early forties. The critics dubbed "God is in the House" a revelation, “the lost evidence of the greatest jazz pianist to ever flat a fifth or empty one.” If you have a really good ear and listen to the Granz recordings, you'll hear that Tatum is playing on a piano with the octaves voiced just a little low and the A above middle C set to 436.

After Art left New York, Horowitz practiced at manic levels as he prepared for a sixteen city international tour. Then one morning, he stopped. Three days befor the tour, he was committed to a psychiatric hospital. Some say he spent thirty-five days in a row staring out the window telling the doctors that he would never perform again until he could play on his swing. Others claim that he would lament that he was not truly the world's greatest pianist, that he was an impostor, and that he dared not face the public again.

In 1954, with no income from concerts, Wanda Horowitz sold the paintings by Raphael and Titian passed to her by her father. Horowitz did not play in public for twelve years and during that period barely spoke to his daughter Sonya. He did record on three occasions in Columbia's Long Island recording facility. After his return in 1966, there were many stories of Horowitz experimenting at the piano with an extraordinary set of variations on “Tea for Two.” The producers, sensing a hit similar to “Stars and Stripes Forever” and “Carmen”, tried to convince Horowitz to put it on record. He adamantly refused. His 1989 will included a provision that no record company ever release any version of his playing “Tea for Two.” No one ever found the tape anyway.

In a chest in dry dark closet in my niece's home in Walnut Creek, inside three layers of plastic bags, there is a 9 inch reel of tape which I now pack with the tape I record now. I remember the afternoon I made the recording all too well. Art and Vladimir were joking around, as they sometimes did. He was most of the way through his second bottle of bourbon and Vladimir had yet again not quite gotten Art to tap his foot when he took on “Tea for Two.” It was 1953 and I don't know if either man was aware at the time that this would be the last lesson.

"It's close though?"

"Yeah, it's close."

"Maybe I can't swing?"

"Nah, everyone swings, we just haven't found it yet. It's there somewhere, it always is. Maybe if you had to play an instrument with bad hammers and three unvoiced octaves in bars full of drunks for a few years…."

I remember the place still smelled like fish. Sonya slipped into the practice studio and tried to get her father’s attention. I smiled at her, but he pushed her away.

“Pappa’s busy, go find your mother.”

I offered to keep Sonya amused as I sometimes did during the lessons, but Horowitz shook his head. His mind was on other things and he wanted me in the room for some reason. He turned to Art with a challenge that he must have considered for some time.

"Maybe I can't swing, but can you play like me?"

Art took a seat at the piano and I taped every second of Chopin’s Scherzo in B flat minor. I could swear he was staring at the keyboard before he set his hands in place. The notes danced from the piano, stately, graceful, and soft. It was music so pure that even now when I listen to it I wonder if there’d ever been an instrument or a pianist involved.

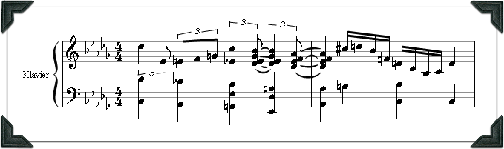

“Carmen Variations (Horowitz)” created by Etincelles

* * *

Marko Fong lives in Northern California and published most recently in Emprise Review, Brilliant Corners, Eclectica, and Memoir (and). He is also the fiction editor of E-chapbook. This is his second story in Lacuna.

What was the inspiration for this story?

This story was based on reports that Horowitz sometimes went to see Art Tatum play and that the two pianists were at least acquainted. I had noticed that both had well-known arrangments of "Tea for Two." Supposedly, Horowitz really did forbid anyone to release his version on record. This story atempts to fill in the missing notes.

6 comments:

Ambitious and accomplished story - very well done!

Excellent story, Marko. I enjoyed it as much this time as the first time I read it.

The depth of knowledge about music and those particular musicians makes the story so real. If I didn't know Marko I would totally believe he was the actual narrator (an 83-year-old man).

A story of tragic genius.

This is great, really fleshes out that story! Though I always thought it went something like when they met, Horowitz played his version for Tatum, and said he'd worked on it for months. Then Art sat down and played a much more dazzling impressive version. When did you write that? asked a flabbergasted Vladimir. "I just did" replied Art.!

Ha, jazz trumps classical, yay!

-/:}>

What a brilliant story, full of twists and turns, I really enjoyed reading this!

Wow. Just stumbled across this story while randomly Google-ing Vladimir Horowitz, (and only because I was listening to a disc.) You can write! Swept me away entirely. Hope you have as long and successful career as Maestro Horowitz. Bravo!

Post a Comment