Against the Current

Townsend Walker

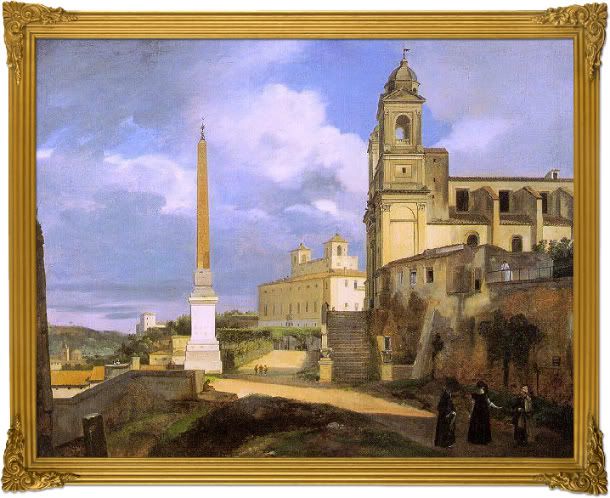

Rosa Bathurst was the sort of young woman who scorned the conventional in her search for adventure. It may have been genetic. Her late father, a secret agent for the British government, was instrumental in bringing the Austrians into the fight against Napoleon. In early 1809 he was returning from Vienna in disguise when his carriage stopped in western Prussia at the White Swan Inn to change horses. He climbed down to stretch his legs and vanished into the dusk, never to be seen again, alive or dead. The one-year old Rosa was taken by her grieving mother to Rome where they installed themselves in a palazzo near Fontana Trevi.

Rosa’s society was the Roman servants and tutors her mother hired, but never watched over. That Rosa was able to comport herself as a proper English girl when brought in at tea time was Phillida Bathurst’s test of her daughter’s education. Young Rosa was naturally bi-lingual, though her early Italian had a marked earthiness to it. Merda and stronzo were heard more often than is common in young girls. She was an aficionado of commedia dell’arte and saw herself in the role of Colombina, the comic servant. Rosa’s impersonation included dressing herself in ragged and patched dresses and wearing heavy eye makeup, borrowed from her mother’s dressing table. In further, and more practical imitation, she became skillful at managing the lives of the maid, the cook and her mother.

When Rosa was seven she declared, “I want a horse.”

Her mother, on the advice of her English friends, bought her a small pony. She was nonplussed when Rosa said, “Oh, how lovely,” and stroked the animal’s pale blonde mane with an absentminded air.

The next day, Count Lucarelli came to call. Tea was taken in the drawing room of the palazzo. The delicate gilt chairs and tables were dwarfed by the enormity of the room with its twenty-five foot carved ceiling: hexagonal shapes colored with gold helmets, red crests and SPQR inscriptions. The floor was mosaic in the roman style of small black and cream tiles in an intricate nautical design.

Rosa served the Count tea, brought him cakes, then climbed up on his lap. “You must tell Mama that to learn to ride properly a girl must have a horse. Ponies are for children and pretenders.”

She kissed him on both cheeks, curtsied and excused herself from the gathering.

“Such a sweet gentle child,” the assembled murmured.

Two days later, a rose gray Arabian colt, with a black mane and tail, was brought into the piazza.

“Thank you Mama, you are so kind,” Rosa said.

Mercurio, named for his color and quickness, and Rosa were inseparable from that day.

In Rosa’s fourteenth year she was sent to London to spend the summer under the tutelage of her paternal grandparents, the Bishop of Norwich and his wife.

“It is not too early for you to begin to acquire the proper deportment and dress of an English lady,” her mother said. “I fear the examples in Rome are few.”

Her months in London were not happy ones. She was ill at ease with the chirping and cleverness that passed for polite conversation in English society or the convention that ruled it. On more than a few occasions she did not hesitate to show her displeasure.

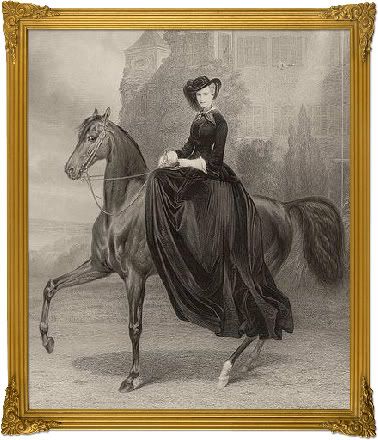

While in London Rosa was invited to the Earl of Derby’s ancestral home, Knowsley Hall, for fox hunting. She arrived to find that she would not be riding, but following the horses on foot. With the promise of her company at dinner, she persuaded a slightly built young man to let her model his turnout and neglected to return it. The following morning she mounted and moved off with the other horsemen into the fields. She might have passed unnoticed had she not been the first to spy the fox. In her exuberance she took off her hat, held it in the air and cried “Tally Ho.” Long Indian-red hair tumbled around her shoulders. She was excused by the Master of the Hunt.

Before dinner that evening the Earl requested her presence in his study.

“Young lady, that was a very foolish thing you did today. Women do not ride to hounds.”

“Are we not capable, my Lord?”

“Not the point; it is simply not done--a woman astride a horse.”

“And if Zenobia or Boudicca, or even Joan of Arc had felt ‘it’s simply not done’?”

“This seems less a matter of national survival, my dear, than a young girl’s fancy.”

“Though how would one be ready if survival were the issue?”

“Shall we go in to dinner?”

Rosa returned to Rome in the early fall. Her black lacquered landau pulled into the courtyard of the palazzo. She waited for the footman to open the carriage door. She was eager to be back in Rome and the freedom it represented for her, but not anxious to face her mother, certain that the Bishop had written about her comportment. Rosa stepped out of the carriage clad in a Regency styled dress of pale blue muslin with matching slippers. The servants and their children, her playmates of months earlier, fell back; her mother gasped.

“My dearest, so like a flower you are, fair of face, full of grace.”

“Thank you, Mama, I have missed you,” Rosa intoned, as would a young woman who’d spent her entire life in English society.

She had grown into a singular beauty; the cooler weather of London had chiseled her features, elongated the formerly rounded face and brightened her emerald eyes. Mercurio snorted and stomped when she came into his stall. She walked up to him and placed her hand on his muzzle.

She started riding with Count Lucarelli’s sons, Gianni and Antonio. Although three and five years older, they found themselves delighted by this flirty and beautiful English maiden who raced with them through the cento storico, terrorizing merchants and pedestrians.

Gianni was particularly taken by Rosa, and she by him. His quiet serious manner was the perfect foil, and audience, for her playfulness. They managed hours together in the gardens of the Villa Borghese.

“You spend too much time with those Lucarelli boys,” her mother proffered one evening. “It is important for your future that you have English acquaintances.

“My future, why worry? Besides, they are more fun than the stuffy English men you bring around.”

“It’s never too early. Lord Grayson and his son Algernon are coming to tea tomorrow.”

The following afternoon Rosa dutifully attended and poured for the Lord and his son.

“I say, dear Rosa,” Lord Grayson said, “What did you think of our London? A splendid city, no?”

“Some find it so.”

“But the music, the balls, the glittering company: didn’t you find it simply enthralling?” Algernon asked.

“On occasion, but the repetition was tiring.” Rosa said. “There is much more enjoyment to be had riding to hounds.”

“You rode to hounds?” Algernon asked. “That’s little done you know.”

“Can only men and boys have fun?”

Lord Grayson excused himself for a meeting with the ambassador, leading his son with him. As the door closed Rosa overheard “not suitable.”

* * *

A fateful Thursday in March 1824, Rosa, Gianni and Antonio were racing their stallions along the Tiber. Rosa was in the fore. On the narrow road between Acqua Acetosa and Ponte Molle, Mercurio’s right foreleg struck a slick rocky outcrop. The horse reared. Rosa turned toward Gianni, expectantly. Her long chestnut hair had freed itself of their ribbons. Her lips were slightly open, about to utter a cry; her eyes dark with foreboding. Rosa’s arms necklaced Mercurio, her sky blue riding jacket against his black mane. Banners of hair, the girl’s and the horse’s, glinted in the sun. Horse and rider crashed into the Tiber, swollen and muddy from melting winter snows. Gianni raced ahead. Rosa and Mercurio surfaced in the eddy of the next bend. He reached out to Rosa, grasped her hand and pulled her toward him. He had her. But Mercurio thrashed, caught again in the boiling current and horse and rider were sucked under the water. Gianni rode on, saw her bob to the surface, dismounted, knelt on the bank and reached for her. Their fingers touched, then she was gone.

Four days later, at Ponte Rotto horse and rider surfaced. Miraculously, Rosa’s face was unblemished. Witnesses claimed that she looked like a marble statue at sleep. She was buried in the Cimitero Acattolico outside the walls of Rome. The inscription on her memorial reads, in part:

FOR SHE WHO SLEEPS IN DEATH UNDER THY FEET,

WAS THE LOVELIEST FLOWER, EVER CROPT IN ITS BLOOM

Townsend Walker is a writer living in San Francisco. During a career in finance he published three books: foreign exchange, derivatives, and portfolio management. His stories have been published in over forty literary journals and included in five anthologies. Two of his stories were nominated for the PEN/O.Henry Award. Four stories were performed at the New Short Fiction Series in Hollywood. His book "A Little Love, A Little Shove: Stories" is forthcoming from Shelfstealers Press in Autumn 2012. The website is www.townsendwalker.com.

Where do you get ideas for your work?

From cemeteries, old plaques on church walls, paintings and other books. The inspiration for “Against the Current” came from the monument for Rosa Bathurst in a cemetery outside the walls of Rome. The tomb inscriptions and plaques are tantalizingly incomplete and the more obscure the person the more freedom for the writer to invent a life. The person’s life span provides convenient time and space frames.

What do you think is the most important part of historical fiction?

Using language that sounds like it might have come from the era being portrayed. The language of the dialogue certainly, but also the language of the narrative. The next part is to nail the details cold.

3 comments:

Beautifully told, Townsend. Great tale. Congratulations.

Great story, Townsend. I like how many different worlds you're familiar with in your fiction.

Townsend,

You have a gift for recreating a time and place with description and language of the time.

Lovely,

Loli

Post a Comment