Do not repent

By Pamela Freeman

I could draw you a diagram, yes, yes, that would be best. See, the castle is here, on the hill, secure, took forty engineers ten years to design that battlement, another twenty to build it with serf labour.

Now, down below, the river valley, yes, see, the river curves like this. You think it's calm, it runs so quietly through the valley but then, here, it turns and falls sharply, white water, rocks with sharp edges, sharp as ingratitude, that's what they call them, the Serpent's Teeth, yes, but there's a path goes up behind the rapids, the old porterage path, before they built the bridge at Pontville they had to carry their boats over the rapids, now everything comes up the river to Pontville and then by road, but that's not important, what's important is this old path, here, see, it comes up the back of the valley and then down to the postern gate.

So come up the river as far as you can then drag your coracle up behind the bushes and go up the path to where it curves down to the castle.

Don't go down. Keep on the line of the path and go up, up as far as you can, yes, yes, as though you're climbing all the way to Heaven on your own two feet, until you can look down at the wards. There's only one spot that overlooks the inner keep, they decided it was safe because it's impossible to get any more than one man up there at a time and it's well beyond arrow shot, so climb until you reach there, look, I'll put a cross where you should be. Now, here, yes, yes, here, there is a way into the mountain. Bless yourself and go through there, find the Cauldron, drink from it and then… well, then you shall see what you shall see.

Just make sure you're shriven and fasting before you begin, and keep all lustful thoughts from your mind.

God go with you, sir. Don't ask me what to expect, no-one ever comes back with the same story. Everyone sees something different, or at least that's what they tell me. They say if you spend a night there you will come down either a poet or a madman. I have seen both come back down the mountain.

Everyone had told her what to expect. She had heard stories about the mountain since she was a baby. Arthur is buried there, they told her. A door to another world, they said. No-one spends a night on the mountain and stays unchanged. A poet or a madman, they said. But it had been a generation since anyone from the court had gone.

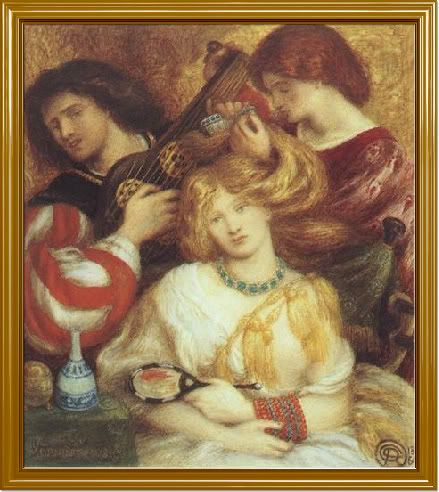

She wanted to be a poet. She was a poet. The court musicians played her compositions, the local bards sang her rhymes. But she wanted to be an acknowledged trobairitz like the Comtessa de Dia and Marie de Dregnau de Lille. She wanted to be world famous, with troubadours singing her songs, sighing her melodies. She wanted her name to be a byword for unfulfilled passion and passionate devotion.

It would help if she were actually in love with someone, but that would come with time. She was only sixteen, after all, and married barely a year. Plenty of time yet to find her true love.

But time was pressing, nonetheless. She had to climb the mountain before she became pregnant. Once she was carrying they would watch her like hawks, safeguarding the heir.

This would be her only chance. Now that the roads were open, Bernard, his father, Seigner Raoul, and his brothers were making their annual visit to their liege lord, the Count; they would be gone three or four days and home in time for Easter. She would tell her mother-in-law she was going on a retreat to the abbey, alone, on foot as befitted a pilgrim, to pray for conception.

It was only a mile outside the castle gates, they could stand at the moat and watch her safely into the abbey guesthouse. The abbess would not lie for her, but neither would she betray her. She was a kinswoman, her mother's half-sister, and she knew better than to make an enemy of the girl who would be Domna at the castle, one day.

So she went to Caligonus, the court astrologer, and got the directions she needed. He was her friend, he had taught her the fundamentals of his craft over the long cold winter: trine, square, sextile. A black art, the priest called it, but looked the other way when the Seigner ordered a natal chart as a gift for a vassal's new-born, or consulted the astrologer about the best day to begin sowing.

Caligonus was a dark, spare man with a mind like a hunting cat's; watchful every moment, with the caution of a practitioner of an officially banned craft, but also with the curiosity of a born observer.

"Na Doette," he said to her, calling her "Lady" in the shortened Occitan style she had yet to become entirely used to, "there is a transit occurring. Nothing is secure; I cannot predict what will happen. You were born under Venus; this is a time of great change for you."

"Yes!" Doette said with delight. "A true change! I will become a great troubairitz, and my cansos will be sung from Castile to Bretagne."

"When we go looking for a miracle, we may not like what we find," he said, and looked sideways at her and stroked his beard. But she laughed at him.

"The Blessed Virgin has me under her protection. I have completed a novena, I have fasted all through Lent, I will give the abbey a fine altar cloth which I myself have embroidered. With the Holy Mother to protect me, what should I fear?"

He was silent for a moment. Then, very gently, he spoke, " Domna Doette" She warmed to the familiar term, her title at home. "Domna Doette, your heart is brave as a lion's and no doubt the Holy Mother will protect your soul from harm. But there are other kinds of harm"

"Who would dare?" she asked. "It would be death to harm me."

"It was not physical harm of which I spoke."

"What, then?"

He shrugged. "Disappointment, the lure of the impossible, a taste of freedom which might unfit you for your position… Domna, I do not know. I only know that my scrolls tell me tomorrow is a night of great change, when the very nations will shift in their sleep. It is not a night to be alone on the Mountain of Malheur."

"It is the perfect night. The only night," she said, and he bowed in acquiescence.

She set out from the castle gate at noon with the whole of the household watching her, from stableboy to cellarer. Her mother-in-law stood with the other ladies at the top of the steps by the main door, waving approvingly. Na Maria wanted a grandson, and this was a very proper pilgrimage for Doette to undertake: short, focused and done without disturbing the household, by which Na Maria meant her husband and sons.

She would light a candle in the chapel and pray for Doette's success. And then she would finish embroidering the neck of that fine linen nightdress, so that the girl would have something alluring to wear when her husband came home. She would scent it, too, with musk. One could pray, but there was no sense leaving everything to God and the Blessed Virgin.

Doette disappeared into the abbey gate, and Maria's ladies rustled around her. The Spring wind was chill, even in the middle of the day.

"To my solar," she said, and the women followed her inside.

Doette picked her way carefully so the rough road wouldn't cut her bare feet. She hummed under her breath as she turned into the abbey gate and went towards the guesthouse.

"Therefore I beg of you, if you please, that noble love

and joyfulness and sweet humility

may so commend me to you

that you may grant me most hope of joy…"

It was a love song by Beatriz de Romans, but Doette sang it to the Virgin. The words fitted. She thought over that for a moment, that a trobairitz's words might be taken by someone else and changed in meaning completely without changing a syllable. It so distracted her that she was three paces inside the guesthouse door before she realised that the abbess herself had come to greet her.

Doette sank into a courtesy and kissed the abbess" ring dutifully.

"Come, daughter," Mother Paulinus said, "walk with me."

They moved side by side to the long cloister. The flagstones were cold under Doette's feet, but they were smooth.

"Well, are you still determined on this ridiculous course?" Mother Paulinus asked sternly.

"Yes, mother."

Paulinus smiled. "So. I have laid clothes and boots ready in your cell, and some provisions. You will attend Vespers and retire to the cell. I do not expect to see you for two days."

"

"And how will you enter the abbey court in broad daylight? You will leave under darkness and you will return under darkness. And then you will remain in your cell for a night, fasting and praying, so that neither you nor I will need to lie when asked about your retreat."

Doette looked at her: the clever eyes, the restrained mouth. This was the wisdom a woman needed to become a power in her own right. For a moment Doette regretted not taking the veil; at least Paulinus answered to no-one but the bishop. But as a nun, the only melodies would have been hymns and psalms; beautiful, but without the plaintive loveliness of the troubadour songs.

She would find power of a different kind on the mountaintop.

"Behold, we have seen him with neither beauty nor comeliness;

his appearance was unsightly.

It is he who carries our sins,

and he suffers for us."

Doette sang with good heart through Vespers. She noted how the melody wavered on the word for "carries" ("portavit"), curving around the B natural note and then climbing on "sins" (iniquitates) to the 5th mode in the next phrase. It was an interesting effect. Perhaps that wavering of voice could be used to depict earthly love…

Next week would be the Passion; the great feast of the church, her confessor at home had always called it, as though it were one word: Easterthegreatfeastofthechurch. She loved Easter Sunday: the dark-church-set-alight conflagration of the Vigil Mass, the return of the Gloria, whose Lenten absence left such a strange dislocation in the Mass, the white vestments of the priests instead of the forbidding purple… Even Good Friday, heart-wrenching though it was, and physically tiring, had a splendour about it… the Way of the Cross, the terrible, tragic afternoon service, the removal of the Holy Body to the Altar of Repose…

She brought her thoughts back to the psalmody

Surely, he has borne our infirmities and our sorrows he has carried.

As always, the act of singing drove all coherent thought from her head. She was a river of sound, her throat a channel through which God made music. Blessed Virgin, she thought as the cantor gave out the strophe, guide my footsteps tonight.

* * *

The moon was only half full and almost setting, of course, the week before Easter, but Mother Paulinus had included a dark lantern with the clothes and food. Doette opened one panel to light her path; from behind no light would show. She found the path and closed the lantern, then waited a few moments for her eyes to become accustomed to the faint light.

It was a rough trail, up along the river and then curving up behind the castle. In daylight she might have been frightened by the heights; in moonlight she was entranced by the silver, shifting shadows, by the cry of night birds, the rushing of the river which covered her footsteps, the sharp scent of rosemary and cypress. She had not been alone, fully alone with no-one within earshot, since she came to the castle. Since she became a wife instead of a daughter. For a moment she thought of Bernard, dining at the Count's table. He would be pleased when she became famous. He was a patron of the arts, an accomplished lutanist, although unfortunately with no voice. He sounded like a crow squawking. She giggled.

At the point where the trail curved down towards the castle, she stopped to catch her breath. The stars were sharp as needles, the pines and cypresses on the hillside whispered. She wanted to sing, exultingly. All alone. She started on the upward path.

"I will go all alone to the mountain…"

She sang under her breath. That wasn't a bad tune. But mountain was hard to rhyme.

"I will go all alone to the- to – through the…greenwood" Yes, that was a good word.

"I will go all alone through the greenwood.." What came next?

The mountain rose under her feet as she hummed and sang, forgetting even shortness of breath and the crowd of stars that seemed to blaze brighter with every step.

At last she reached the little platform from where, in daylight, one could look down on the castle. She opened the lantern and searched for the cleft in the rock. Now, for the first time, as she stared at that slit of darkness, she felt nervous. Not afraid, exactly (what did she have to fear, being under the protection of the Blessed Virgin), but with butterflies in her belly and her breath coming a little short.

She held the lantern high and entered.

It was a passageway, leading down, the floor strewn with rocks. She picked her way carefully, giving it all her attention and therefore less aware of her fear.

She watched the floor so carefully she had taken three steps into the cavern before she realised.

She had heard of places like this, where the very stone grew into strange and sometimes miraculous shapes. High, huge, the cavern stretched out further than the light from her lantern could reach. Astonishing. Glinting, coloured… she wandered among the pillars and almost-statues in a daze. There was a stag, antlers raised; an eagle, wings stretched for flight; two spreading trees, oaks, so lifelike that in the flickering lantern light it seemed as though leaves moved in the wind… a man.

A man. A true man, no stone shaping. He bent and lifted water in his hands, and drank, then stared at the rough blob of stone before him as though bewitched, a candle on the ground beside him. She drew in her breath sharply, and the whispering sound travelled and echoed around the great gallery. The man - a young man - jumped and staggered back, knocking his candle over. It went out.

"Don't be afraid," she said urgently, and the cavern sang back to her, affffrai affrai affraidddd. How ridiculous, she thought, that I should be reassuring him.

He looked from her to the blob of rock. "Mother?" he said, so softly that the cavern only hissed thertherther. He went down on his knees.

Doette had had men kneel to her before. Serfs, troubadours, pages, of course. But this man was an adult and, from his voice and clothes, no serf. And she was no-one's mother.

She came nearer. His hair shone in the lantern light like autumn leaves. He fixed his eyes on her and his eyes were as blue as Our Lady's Mantle. He reached his hand to her and his hand was beautiful.

"I am no-one's mother," Doette said, whispering. Ss Sss, went the cavern.

"Domna," he said, shaken. "I thought…" He looked again at the rock. Now she was closer, Doette saw that from this angle, the rock looked very much like a Madonna and child, with a curved rock beneath it that held water. No wonder he was shaken. He had been thinking of the Blessed Virgin and then she had appeared.

She giggled. The cavern giggled back. He smiled reluctantly.

"You are a light-hearted visitation, Domna," he said, but his voice shook. The cavern echoed him, but she had stopped listening to the cavern.

"No visitation, seigner. A pilgrim, like yourself, I think."

"They told me that no-one came here anymore."

"No-one does. It has been a generation since anyone in the valley dared the mountain."

"And tonight, after so long, the two of us? What Fate has brought us both here? Would you be a poet, Domna?"

She stiffened a little. He was older than she, but not by so much that he could question her.

"I am a poet," she said. "I want to be a great poet."

"Then you must drink from the Cauldron," he said. He looked from her to the rock as though he saw her face there, as though she were truly a visitation.

She stepped forward, cautiously, and bent to cup water in her hand. It tasted strange, like chalk and metal. The edges of her tongue furred. Then she straightened up.

The lantern lit his face from below, casting the eyes into shadow, the hair into a halo. A saint in a stained-glass window, she thought. Saint Christophe, patron of wayfarers, protect us. Saint Anne, patron of good wives, protect me.

But it was far too late.

* * *

He was a troubadour, of course. His name was Oliver. Not quite noble; the bastard son of a baron from Normandy. He travelled the world, as such men did. He would leave in the morning, and never return.

They sang together, notes rising in perfect pitch towards the invisible roof, as though in a cathedral, as though in prayer.

They sang Pistoleta's duet Good lady, give me your counsel, and Down there in the meadows and then, as he stood watching her from the shadows, tears on his cheeks, Doette sang the Comtessa de Dia's I have been in great perplexity.

"My love, handsome and good,

when will I have you in my power?

If only I could sleep with you one night

and give you a loving kiss!"

She had never sung like this before, as though the song came from her heart with no need for thought, as though the notes were truly hers, not learnt from some troubadour for a guerdon, for a silver penny.

He sang a new melody for her, the words coming from nowhere:

She is the light of the world

That Lady of my heart

Surrounded by glory she comes

Where she is there is no shadow.

His eyes were blue as forget-me-nots, as blue as cornflowers. His hair like bronze, as fine as silk. His voice a thick brown velvet ribbon, soft and plush with clear edges. She could have drowned in that voice. She could have lived in it forever.

She was married. He was unobtainable, unsuitable even if she had not been. She thought, I wanted to become a byword for unfulfilled passion and passionate devotion.

His name was Oliver. She wrote many songs about olive trees in later years. Bernard thought it was in nostalgia for the olive groves of her youth. She sent them out with troubadours and jongleurs, hoping he would hear them and understand.

Down there beneath the olive tree

- Do not repent –

A clear spring wells up.

Dance, girls!

Do not repent

of loving faithfully.

They marvelled from Castile to Bretagne that she could write so feelingly of love, who was so chaste, so faithful to her husband. In all these years, there had been no whisper of a love affair, not even of the pure love allowed between lady and knight.

You do not feels the pangs of love as I do, she wrote.

Perhaps he did not. On the morning she went to be churched after her third child, another boy, the choir sang a new hymn to Our Lady in her honour.

She is the light of the world

That Lady of Mercy

Surrounded by glory she comes

Where she is there is no shadow.

It was composed, she was told by the chorister, by a monk in the Cistercian order, who was making a great name for himself in church music. Brother Revelatus.

"His new Mass is eagerly awaited," the chorister said. "I am sure your ladyship would be pleased with it."

She nodded. "I will pay for you to have a fair copy made, Father. The glory of God shows itself most clearly in music."

He beamed and thanked her and watched her walk away, the baby in her arms. The living image of Our Blessed Virgin, he thought. Anyone who sees her sees God made manifest on Earth.

She went home and cried over her lute, then took it up and finished the song she had begun on the mountain, so many years ago.

I will go all alone through the greenwood

since I have no company.

Pamela Freeman is an award-winning author of 23 books for both children and adults. Her novel, The Black Dress, won the NSW Premier's Literary Prize for Historical Fiction in 2006. She is best known for historical and fantasy writing, but has also published in crime and science fiction. Her most recent books are Ember and Ash, a stand-alone fantasy novel for adults, and Lollylegs, a short children's book about a very cute lamb. Pamela's books have been published in the UK, USA, Italy, Indonesia, Canada, Korea, Germany, France, Portugal and Spain, and are distributed to India and South Africa. Pamela is a Doctor of Creative Arts (Writing) and also teaches at the Sydney Writers" Centre (face to face and online).

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

Mostly I answer: "I don't know" to this question, but in this case I got the idea while I was listening to 12th century troubaraitz music and was struck by how many of the original songwriters were women. The story came out of real songs of the period--the ones which are attributed to "anonymous". I started to wonder who might have written them and why...

What inspires you to write and keep writing?

My husband says I'm not inspired, I'm addicted… and I think he may be right. I think it's also true that I write the stories I'd like to read but can't find anywhere, so if I'm going to read them I have to write them first!

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

I think there is a tension between creating the characters in a way which is truthful to their reality - for example, belief in God or hell or the divine right of kings - while making them comprehensible and human for the contemporary reader. I hate historical fiction which is full of "modern" characters in historical dress; that is, where the modes of thought of characters are profoundly modern rather than arising out of their upbringing and environment. This is part of world-building - but it's also, deeply, a question of imagination. It takes a huge effort to imagine oneself into a medieval mindset fully enough to write a novel, for example. Part of that is research, of course. The more you know, the easier it is to be faithful to the characters" reality.

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?

I think humans are fascinated by other humans - we are social creatures. And we learn about ourselves by seeing how others have been or could be different to us. Historical fiction shows us ourselves in a new light. And it has some of the best stories!

What advice do you have for other historical fiction writers?

Do your own research. So often I have found ideas for plots and characters arising out of my own reading. I am currently researching 13th century Italy for a new series and the more I research, the better my plot gets!

1 comments:

Gorgeous!

Post a Comment