On the Appearance of the Wolves

by Edgar Mason

By the grace of God – I am obliged to say that, though I couldn’t be farther from feeling it – I am the emperor of the East; by the grace of Eutropius, the husband of Eudoxia; by the grace of some hideous misunderstanding, I have come to rule over both an empire and Empress that will not be controlled.

And thus, the wolves appear.

I was unprepared for this. I was woefully unprepared for any of this. I did not expect my father to die; I did not expect him to leave me the throne. He should not have left me the throne; he should have given it to someone else, anyone else. A beggar in the street would have been more fit to rule than I. I was raised among the gilded pillars of the palace – no, not the palace – many palaces. Running about through gardens and fountains is no way to become an emperor. No way at all.

They hailed my father as “the Great” before his body had even reached the capital. The only man more powerful and more beloved was the very Bishop of the west, and he gave the funerary oration.

I was raised in the golden corridors of the palace, and nowhere near the battlefield, nor the speaker’s podium. I was brought up to be a prince; nothing more. I remember my tutor said as much to me when I was young. He was an old man, brought from Alexandria, and his skin looked like cracked, dry dirt. He was a learned man – though later he was taken away; I don’t know why.

But he said to me once, “Thank God, Arcadius, that you will never have to rule. Thank God you’ll have advisors and wiser men, who know Pythagoras’ theorem and how an army should be led. Thank God for those men, Arcadius, because you are a fool.”

My old tutor was right. I am no emperor. I am no leader of men. I lack even the physical characteristics: My face would be more at home on some fresh-water fish; my limbs are long and thin as they dangle from my torso. That is all a sign, surely. And I lack any form of ambition, really – my only wish is to remain in bed in the arms of my lover, and see no one else.

My father was called “Great.”

How does one live up to that? What does one do?

I was lucky Eutropius presented himself; I was lucky the Magister Militum presented himself. I suppose I was lucky, at any rate. They seemed to know what they were doing.

I was probably wrong to trust in them. But how was I to know that? I was named – my name, even, turns against me – for some unearthly paradise, and I have never known the right thing to do. I have always been able to trust in others; it is how I was raised. I was brought up to trust in others, in some far off God, in some other person, in my own great, beloved father. So trust in them I did, because they… Well, they were there and these things come to us as they will.

I have been told that Eutropius schemes behind me and about me, and I know that the Magister Militum is. Eutropius has sold provinces from under me; the Magister Militum has attempted to take them outright. The problem is, I would not know what to do without them. They are what I have in place of my father’s genius.

I loathe my wife. It is an open secret; the entire city – the entire empire – knows of it. My slatternly wife, with her hair combed down like a common courtesan. She is beautiful, I suppose. She is a barbarian by descent, and she changed her name to sound more like one of the ruling class. She has the pale skin and hair of her people, and it glows in the sun against her purple robes and golden jewelry. They say that she is beautiful and cultured; I know only that she is hideously arrogant and terribly unpleasant, even to have in the room.

I knew it from the moment we were married, the moment we were alone together. For at that moment, she tore off her bridal veil, turned to a Western vase – that clear, shiny thing, so difficult to come by still intact and so worthless and ugly in a room – fixed her hair, then turned to me.

“You’ll let me do as I like,” she said. She smiled closely, as if she knew some secret. “You’ll let me do as I like, and see whom I please.” She took a step closer to me, her soft, soft sandal making not a sound against the cool, stone floor. “I’ll do the same for you,” she breathed, eyes half-closed and heavy with kohl. Her eyebrows, I saw, were pale beneath the kohl she’d used to draw them in, and her thick, blonde hair was held out in rolls by lambswool. Everything about her face, down to her very smile, was false. She is a liar, and she is vain. I knew this in that instant – and then she said, “I’ll do the same for you, because I know your secret.”

For all my many faults, I am at least honest enough to know that I have them.

That was Eutropius’ doing, making her my wife. He was right to do it, but I cannot forgive him for it. He has made amends, and more. He has done a great deal for me, and it is improper of me not to forgive him for her, after all he has done in exchange. But I cannot. I cannot. I loathe her too much.

It was the bishop. Chrysostom, The Golden Mouth. Eutropius was hiding… the Magister Militum was out for him. He wanted Eutropius’ blood; I don’t know why.

That’s the problem with the two of them. I know they’re both very good at their jobs: The magister militum keeps us all safe from barbarians, and Eutropius – well, I suppose Eutropius, if nothing else, makes sure that there is gold in our coffers.

And the Golden Mouth… It was all very confusing. Apparently – well, I was there. Words were spoken, harsh words, by the Golden Mouth to everyone in the city, on the subject of Eutropius. He speaks beautifully, the Golden Mouth, but he does tend to say things that he shouldn’t. Everyone was bewildered, but we found out eventually. And then… Well, I don’t know quite how these things happen. It seems that that sermon about vanity was all about my Eutropius, but I can’t believe that. I’m much more ready to believe that it was about my wife.

She was the one to exile the Golden Mouth. It was she; I’m sure of it. Only so loathsome a female would be foolish enough to exile so holy a man. She was the one; I suppose she took the homily too personally.

The populace is unhappy. Rightly, the populace is unhappy. The empire is a joke, it’s for sale – there’s a card with the going rates. Either I or Eutropius – it’s questionable where I end and he begins, sometimes – have acquired a number of villae and fine titles in exchange for far-flung provinces and suchlike. Lucrative, for someone, I suppose, but I don’t believe that there is a single man in the empire – nor, indeed, a former man, such as my Eutropius – who could honestly say that that is how an empire should be run.

What am I writing here? I am no one to say how an empire should be run.

* * *

My bedroom is beautiful. My bed is covered in silk and soft linen; my walls are decorated with bright frescoes and tiles. My windows are covered by fine, fine curtains and the breezes blow cool above the city. I have statues taken from the far corners of the empire, and furniture inlaid with precious metals, and my bed is softer than any other.

I do not share it with my wife, thank God. Eutropius is the servant of my chamber, and he takes his role seriously.

His face is ugly and yellowed, I know this. He is as bald as an egg; God knows why (well, actually, I know why, but we are careful). But his hands – my God, his hands. So smooth, fragile and trembling, like old silk. A tenderer caress cannot be found anywhere in my empire.

The bishop is gone. My wife’s doing, perhaps, but the fact remains: The Golden Mouth is gone, and the portents have begun to appear. Birds. Entrails. Clouds and stars.

God only knows what may happen unless my wife will mend her ways. Or if Eutropius can be made to disappear.

I would sooner lose my wife than my lover, but I may have no choice.

It was terrifying, the most terrifying thing that has ever happened to me.

I was on the parade ground, dressed in that hot, uncomfortable armor that I am forced to wear for no reason but to put on a show. My horse was restive in the hot, wet air; I was sweating fit to drown the poor creature.

The troops were in mid-wheel when I heard shouts. Cries rose from some of the soldiers as they broke ranks and ran towards me. They had their spears leveled at my horse.

Is it perhaps telling that my first thought was, “Mutiny”? I am no horseman, but with my own troops charging towards me, I – I think understandably – tried to turn and run, but I couldn’t. My horse had taken a fright; I was almost thrown.

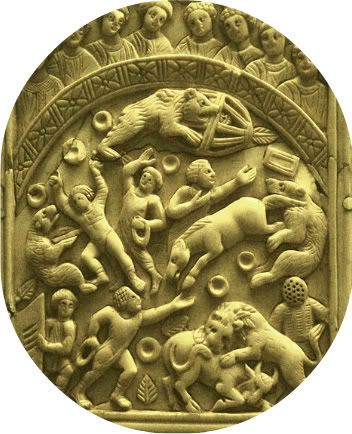

Hands held my horse; hands pushed me back into the saddle. Voices cried in terror, and mine soon joined them: Circling below my feet, around the feet of my horses, were three wolves. They were great, skulking, muscular things, with black fur and slavering, hungry jaws. Their eyes were ravening, golden even in the gray light. Someone screamed – to my shame, it was more than likely me. Suddenly, one of the soldiers that had charged me struck a mighty blow – I could never strike such a blow – against first one, then another, of the wolves. The creatures screamed in pain, and their fellow tried to run – but it, too, was caught on the blades of my soldiers’ spears. Blood burst from the creatures as the soldiers slew them.

Brusquely, the drillmaster slit their throats, ensuring their death. Someone drew my horse back as the soldiers fell upon the wolves, for a wolf skin is a valuable thing. And then another cry went up, washing back from the soldiers like ripples in a fountain.

For when the wolves’ bellies were slit open, inside were human hands. White hands, amidst the red blood that pooled inside the black bodies of the beasts. And then the gray and lowering sky, the gold and much-marred sands of the parade ground…

My gilded life is gone.

I feel the hands of fate upon my shoulders. I do not know what I should do now, nor how I should act. Do I incur the wrath of my wife by summoning back the Golden Mouth? Do I dare to act in such an… acting way? Or do I cower and allow someone else to make the decisions for which I am so ill-prepared?

I do not know.

But I saw the pale hands in the wolves’ bellies, and I know this to be a sign.

When not grubbing away at Greek and Latin, Edgar Mason can usually be found reading, writing, knitting or wandering around trying to figure out where she's supposed to be. Her work has appeared in Eternal Haunted Summer, Bull Spec and The Lorelei Signal, among others. She is inspired to write by people around her, Great Literature (with the caps) and Giorgio de Chirico, to name just a few, and continues because she hopes one day to bring joy to the world through the power of words (no, really!). She blogs at http://radiosaturday.blogspot.com.

1 comments:

Accomplished and deft. The author has clearly benefitted from grubbing around the odd corners of Greek and Latin.

Post a Comment