Ufuve

by Maude Larke

Introduction

These four fragments seem to be all that exists of the tale told in them, and indeed of the culture that produced them. They are believed to have been carved into their support (a block of wood which seems to have formed a pillar or doorpost to a house) by the sea captain himself; his exact reason for referring to himself in the third person and for speaking in the past cannot be explained.

Hopefully, other such fragments will be found in the same bed of sedimentary rock that is being excavated in Ashkelon. They should both give us more information on the culture referred to and confirm or correct the translation presented here. We thank Professors Burgess and Lodge, members of our team, for their competent study and able rendering of his extinct language.

Dr. F. I. Iskandar

Head of Operations

Ashkelon Archeological Project

Hsn, the Unnamable, the Warning, spoke its name with each clawing on the edge, eternally murmuring of its dread longing. The dwellers by the rippling blue beast readied their sea-houses, their light tundi-hsndi, to take the good hand of the deep motion, and to step through the claws to their neighbors, the Fen-hsndi.

They were an old people, older than the enduhdi along the shore to the north, and little understood the ways of the new-comers. The Fen-hsn writings were like the knock of their mattocks against their ship timbers; but they, the Elioduhdi, wrote like the waves, like the blowing sands about them, like their home. And the Fen-hsn worship was strange, and was scorned by the Elioduhdi, for they worshipped only the white head of Zyrj, and believed not in the old Waiting.

Zyrj is a beast that turns its cold back outward when it sleeps and its warm belly when it is awake. Its belly is bright blue, its back black, dappled white. Its eye is bright and its head is white, and sometimes when it sleeps it covers it head with its black paws. Sometimes the beast is molbrunu, angry, and its fur is ruffled and gray. This the Elioduhdi say.

By a cord around the neck of Zyrj hangs Elio, that which was. And under Elio is Ufuve – the Ending.

“Elio ihto Ufuve,” the priest, the qelduh, chanted every morning to the fishermen as they prepared, and to the traders of goods as they made ready.

Elio ihto Ufuve,

Ufuve ino qelde;

Elio grinta huldo,

ui Ufuve mol huldo . . .

And on they chanted to protect the men.

“The Earth hung over the Abyss,

The Abyss lay under waiting . . .”

On, while Hsn the Unnamable Warning, the blue claws of Ufuve, struggled to pull firm Elio into itself. And on the prows of their ships was written to defy the claws, the waves,

“Elio grinta huldo”; the Earth was called bright.

The ships were loaded, the qelduhdi ended the ritual drone, and the leader of the trade ships signaled to his men. The long tundi-hsndi were thrust into the hands of Hsn, and the men felt the smooth stroking motion of the blue paws. They worked quickly, lightly, they knew by the gentle rocking that the beast was not hungry today, that they were far from Ending and Elio was still strong and bright. And they gloried in the breath of Zyrj giving them speed, and its bright eye approving their sailing, and the strength of their tun-hsn prows.

And when they went far, and saw the sands of the Fen-hsn shores, they turned to Elio and the blue claws lifted them to the beach, thrust them there, carried them vigorously to the shore and the welcoming cries of the Sea-comers.

The men all knew each other, greeted each other with their own people’s words, gave news to each other. They had traded together a long time; they worked together, easily loading and unloading the foods and cloths and animals and woods from ships to land and land to ships. When the work was done, they sat together and shared their meal.

One of the Fen-hsn leaders began talking good-naturedly with the Elioduh captain in the old tongue. “It seems your old beliefs have spread. We hear of a man to the east, a Hipporu. We hear he is building a great tun-hsn, and he wants to put his own Elio inside it. He says the voice of Zyrj came to him, telling him of Ufuve, and how this man must save life from it.”

“He is a madman,” replied the captain. “Everyone knows that there is no saving life from Ufuve, should it choose to come.”

“Well, he is serious, and has done great work. He has three eliedi, and they are helping him.”

The captain was more solemn then. All his people worshipped their own eliedi, and were glad for having them there, a sign, a proof of the strength of Elio. He himself, this captain, had an elie, now grown, and ready to become a qelduh, one who waits.

The Elioduh captain, all the Elioduhdi, respected the Hipporudi, but stayed apart from them. Hulduhdi they called them, Those with Names, for they had come to the land from the east with their own name, and held strongly to their own ways. They did not wait either, but worshipped a being called He Who Is Called So by the Elioduhdi, for they gave him no name, these strange people. Marvelous and strange they were, and the Elioduh captain wondered that a man who ran from the Warning Sea and lived in land could build a tun-hsn, and teach his eliedi to build also.

The captain then laughed and said to the fellow-captain of the Fen-hsndi, “The ways of the Hipporudi have always been strange, and they often seem to be more molenu than we. This must be simply another example. And if the eliedi follow their elqeldo in his madness, it shows that madness comes from the father as beards do.”

And he stood and called to his men to re-enter the grasp of Hsn.

Time passed, Zyrj rolled his blue belly and black back and flashed his bright eye, and the tradesmen forgot about the crazed Hulduh. The great Warning grasped at the sand, the priests chanted, and the people continued their simple lives by the sea.

The captain worked, kneeling under the bright eye, scraping the bottom of his hollow ship out of reach of the claws. As he worked and his brown arms flexed, his elie, dark and lean, came to him.

He watched his father work hard, waited until he stopped to breathe, and spoke to him.

“Elqeldo, father, . . .”

The strong father turned and placed his strong back, shining like Hsn, against the still wooden curve of his strong tun-hsn, and smiled. But he saw the eye of his son, dull like the eye of Zyrj in the cold, and waited for him to speak. The eye searched longer, like an Elioduh too far from shore, and the younger one said, “Strength to strength.” The words were enzyrjuha, a breath from the sky.

“What is this, ‘strength to strength’, enogrintaduh?”

“I see your back, strong, against the ship, strong. Strength put to strength . . . That is what Ufuve will be like.”

“Ah, elendo, you are inu-uha. Sit here in the warm sand by me.”

“Yes, I am inu-uha, my elqeldo, and I am uhazyrjenu, too.” He sat down and folded his legs. “I am restless. It is Ufuve, the strength of Zyrj to the strength of Hsn, pulling at Elio like pulling apart water reeds. It is a world of pulling, like the oarsman against the waters, until the oarsman’s strength fails.”

“Elie elendo,” spoke the father, “you see too much the mol, the dark of things, and not enough of the grinta. You see strength to strength, and you think Ufuve. I see strength to strength, and I think Elio. I see the strength of my back and the strength of my tun-hsn. When we are out on the blue claws, these strengths are together and together they keep us from Ending. Together they bring us to Elio.”

“Yes, father, you are right. I see too much the mol.” He stopped and looked out along the still sands. Then he said suddenly, “Elqeldo, they say that I may not become a priest. They say that the qelduhdi may choose against me.” He lowered his head.

The captain looked at the young bowed head, and knew a sad heart held it bowed.

“Yes, my son, that may be so. The qelduhdi remind us that we are still waiting, and that we will still wait. They are our strength in Elio, and our trust in it.”

“And I,” spoke the son with gloom,” with my spirit molenu, cannot keep this trust. Because ‘the Earth is named bright’ but I see just the dark. I cannot be a qelduh if I cannot see the bright.”

“But you can see the bright,” the father answered, and sat up to his son. “You see it often, but you forget, you let the darkness come in like molzyrj. Yesterday you rejoiced in the ihtuzyrjuha, as it only lifts its wings and Zyrj brings it upwards to him. ‘The small creature is nothing but trust,’ you said, ‘and its trust is its brightness.’ You saw grinta and Elio in the little ihtuzyrjuha, and the brightness was in you too for the rest of the day. If you had not been uhazyrjenu and molenu when you came to me, you would have seen Elio in my strong back and tun-hsn, too, as I did, and you would have felt the brightness again. The trust of the Waiting is in you. You need only keep your sight from being drawn away. You need only keep the mol away for a while, then you will become a qelduh, and then you will be able to keep the brightness always in you.”

The son lifted his head. “Yes, father, you are right – and it is always better when I talk to you.” And he said, “Yes, they say that when a man is a good qelduh he never sees molzyrj again, for the brightness is so much with him. If molzyrj will be gone, so will the inner darkness, and I will not be molenu . . . I want to be a good qelduh.”

The father smiled, and turned from his son to work at his boat again. “It is good to see grintabrun in you.” He scraped a while and said to his son, with a larger smile, “You are like an old Hulduh, you are.”

“I, and old Hulduh? Why do you say that, elqeldo?”

“Because they think of the mol, like you do, but more. They have rarely the bright in them. Their smile is of craft, not joy. They know too little grinta, and it makes them foolish, even before they are old. I have had news. There is one now, an old foolish one, so foolish his own people laugh at him. He has heard someone talk of Ufuve, and it has him so frightened that he is trying to build a tun-hsn large enough for Elio. I am glad that you are not a madman like that.”

He looked up from his work and wished that he had said nothing, for he saw the eye of his elie, dull like the eye of Zyrj in the cold.

III

The men stood outside the great tun-qeld of the Elioduhdi, the wooden temple, made from Fen-hsn wood bought with Elioduh fruit and sheep. They were waiting for the priests to come with their sons, waiting for the ceremony that would bring qelduhdi among the eliedi to continue the Waiting. Zyrj was molbrun, ruffled, gray.

One group stood apart from the rest, talking loudly with many gestures. With them was the tun-hsn captain, looking serious and thoughtful.

“He has a tun-hsn, very large, built of timbers and pitch, standing on dry land, far from any river. He is filling it with food, and pairs of animals, and is shutting himself and his family inside,” said one.

Another joined, “And his eliedi! One elie has a name like the sea, has the name of the Warning. He is called Shm.” He pronounced the son’s name well, in spite of the strangeness of the sound for Elioduh mouths.

The captain spoke quietly. “This Noa is a Hulduh, and knows nothing of the Waiting, or of the sea. The Hulduhdi do not speak the words of the sea, so the name of his elie means nothing. He is a madman. He heard of the Waiting, and it made fire in his broken head.”

“But he has built,” said another. “He has built a tun-hsn, and his people know nothing of ships and seas. He has talked of the waters, and his people know nothing of Ufuve. He has – ”

“What do the qelduhdi say?” asked the captain.

“Nothing. They still ponder,” said one.

“Do you mistrust your own priests?” he asked.

“No,” they answered.

“As you trust, they will tell you. And if they only ponder, and do not tell you, then it is because it is not yet time, I believe. Ufuve is not yet. Trust the qelduhdi.”

As he said this, the chant began, and the priests walked slowly through the crowd of men and entered the wooden temple. They were followed by the eliedi of the people, coming to be made into those who wait for the others to come. The sea man watched as his own elie walked by, young and lean and dark and straight, calmly walking to enter the temple. The elie looked up at dull, molbrun Zyrj, and his eye became dull. He looked back at his father and his dull eye became wide. His father wondered at this.

The men waited and stayed outside, and listened as the tale began,

Elio ihto Ufuve,

Ufuve ino qelde;

Elio grinta huldo,

ui Ufuve mol huldo;

As the men stood outside waiting, rain began to fall.

In the rain, the gray, heavy rain, the captain ran and stumbled through the rivers in the lanes of the village. Muddy water to his knees hid the mud of the street, and he stumbled and lurched and pulled his feet from the mud as he ran. He ran from the village, through the flooded fields with rotting grain, past the fields where sheep lay sick or dead in the water. He ran for his house, his tun by the Warning, his hut by Hsn that held his family, stumbling in the pounding rain.

His face was a block, but his eyes were bright as he ran up to his doorway and went in to where the members of his family sat on the table to keep their feet out of the water.

He walked up to the table and stood in the pool of water in his own house. He looked at his wife and said, “Ufuve.”

The word, half whispered, sent a trembling through his wife. The children looked up in wonder.

“If it is the Ending, then why are your eyes so bright?” the wife asked.

“Because it was our son, our own elie, who knew and proclaimed the ending. Our son was the one who knew.”

The captain waded to the window and looked out on the hard rain pouring and felt the chill from the dampness. He watched as he knew the Warning would rise up and grip him in its blue claws and swallow him, and he was happy because he was dying proud of his son who knew of Ufuve. He had trusted in the qelduhdi, and Elio had given him reward by learning of the world’s end from his own elie.

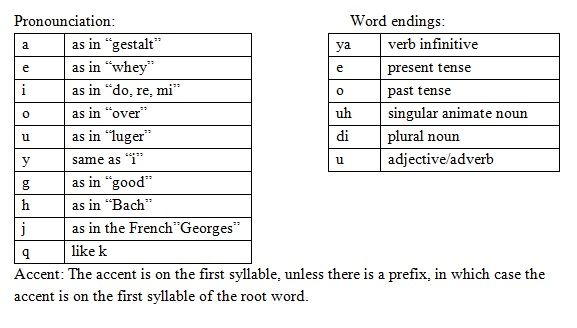

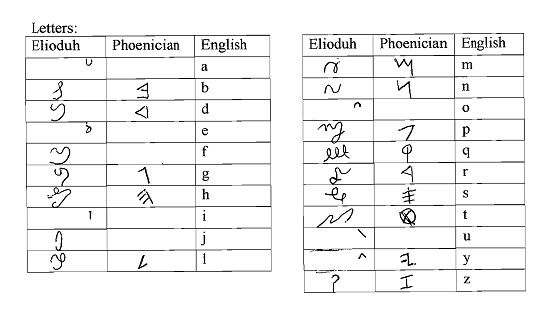

LANGUAGE OF THE ELIODUHDI

The language of the Elioduhdi is like the languages of other Middle Eastern peoples in the use of diacritic marks for vowels and in the writing of the language from right to left. It is unlike the other languages in that its letters are formed in a curvilinear style, while those of the other languages use mostly squared or angular shapes.

The Elioduh language was apparently borne of imitation of the sounds of nature, most particularly the sea by which they dwelt.

brunzyrj – “eye of the sky”; sun

el – first

elendu – “first-come”; first-born

elie – “he who is”; son (pl. eliedi)

Elio – “that which was”; Earth

Elioduh – “he who was”; member of the Elioduh people (pl. Elioduhdi)

elqeldo – “first-waited”; father

enduh – “comer”; a stranger or member of another people

enduhgrinta – “one who came bright”; a term of affection

enogrintaduh – “one who came bright”; a term of affection

enya – to come

enzyrjuha – “a breath from the sky”; inspiration

f – of

Fen-hsn – “sea-comer”; a member of the people living north of the Elioduhdi (pl. Fen-hsndi)

grinta – bright

grintabrunu – “bright-eyed”; happy

grintazyrj – “bright sky”; day

Hipporu – man of a people living inland of the Elioduhdi (pl. Hipporudi)

Hsn – the sea (thought to be part of Ufuve)

Hulduh – “the one named”; the Elioduh name for the Hipporudi (pl. Hulduhdi)

Huldoduh – “he who is called so”; Elioduh name for the Hipporu god

huldya – to call or name

ihtuzyrjuha – “over sky’s breath”; bird

ihtu – over

ihtya – to hang over

inu – under

inu-uha – “under breath”; physical or mental doldrums, listlessness, melancholy, sadness

inya – to lie under

mol – dark

molbrunu – “dark eyed”; angry

molenu – “come dark”; pessimistic, depressed, negative; mad

molzyrj – “dark sky”; night

molzyrju – “dark-skied”; tired

qelduh – “one who waits”; an Elioduh priest

qeldya – to wait

tun – house

tun-hsn – “sea-house”; boat, ship

tun-qeld – “waiting house”; temple

Ufuve – “Ending”; the Abyss of Elioduh mythology

uha – breath

uhazyrj – “breath of sky”; wind

uhazyrjenu – windy (day); restless (person)

ui – and

Zyrj – the sky

APPENDIX B

THE RELIGION OF THE ELIODUH PEOPLE

The only surviving portion of the Elioduh liturgy is a set of phrases contained in one of the extant fragments found so far.

the Earth hung over the Abyss

the Abyss lay under waiting

the Earth was named bright

and the Abyss was named dark

This people’s faith seems to have been rather apocalyptic, involving waiting for a cataclysm.

Maude Larke has come back to her own writing after working in the American, English and French university systems, analyzing others’ texts and films. She has also returned to the classical music world as an ardent amateur, after fifteen years of piano and voice in her youth. Winner of the 2011 PhatSalmon Poetry Prize and the 2012 Swale Life Poetry Competition, she has been published in Naugatuck River Review, Cyclamens and Swords, riverbabble, Doorknobs and BodyPaint, Sketchbook, Cliterature, and Short, Fast, and Deadly, among others.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

This story was inspired by my probing of Biblical texts. Often they put me in a "what if" or "what was it like before this" mode.

What inspires you to write and keep writing?

MUSIC. I need to choose carefully what I listen to while I'm working.

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

Creativity. Historical fiction can become very mechanical. Lobbing in the facts rather than creating the scene.

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?

The recreation of the scene, the "what was it like" question answered.

What advice do you have for other historical fiction writers?

Read Dorothy Dunnett's "King Hereafter". THE piece of historical fiction, in my humble opinion. I cried at the end.

0 comments:

Post a Comment