Coming Home

Townsend Walker

Buda, 1839. Colonel Janós Hajdú strode out of Cavalry Headquarters cursing his commanding officer.

General Bauer had been brief. “Hajdú, there are rebel bands in Borsod County. They’ve stepped up their activity in the last three weeks. They attack then disappear into the countryside. The local garrison can’t stop them. You know the land better than anyone. I’m giving you five hundred men. End this.”

The General was asking Janós to suppress a rebellion fomented by people he had grown up with, people he knew.

Bauer stepped closer. “Hajdú. Do it quickly. Vienna is watching.”

As Janós mounted his horse, deformed images surged through his brain: streams he swam in as a boy flooded and running red like those in the Carpathians; fields he had worked in, flattened and strewn with trampled crops. His orders horrified him, but he would have no other commander charged with this mission. No one would do it as carefully, or as well.

The mess hall glimmered with candlelight and its reflections off the heavy gold braids on the hussars’ white jackets. The walls were draped with campaign flags and banners. Janós was greeted with a loud huzzah. He appreciated the acclaim, but would not let it register. Morale of the units under his command was always high. Many in the room owed their lives to his swiftness in checking an unnoticed sword or diverting a thrusting spear or to his battle tactics—he was a scholar of strategists from Sun Tzu to Napoleon. Janós was proud, some of his superiors complained “to the point of arrogance,” of never having lost a battle, and of the rarity of casualties to his men.

While port was served, he addressed the officers. “Gentlemen, this is a not an easy mission. We are being asked to suppress a rebellion of Hungarian peasants. I am Hungarian; some of you are also. But do not confuse your sentiments with your duty.”

He turned to the wall map of northern Hungary. While showing the volcanic cliffs and caves dotting the Bükk Mountains west of Miskolc, he remembered the lingering smell of sulfur mingled with the anise of the beech trees that wooded the area. To the east and south of town were foothills; beyond, wheat fields and villages. His voice thickened thinking about soldiers quartered in the country he’d ridden over as a boy and in the woods where he’d hunted. He felt a humid summer heat and heard the whirr of flies over bodies littering the fields. Not the fields of Lombardy, but his fields, the ones his family owned, that he now owned, the ones tilled by his tenants, Imre and Katalin.

“In small units you will hide in the foothills and pastures so you can capture the rebels as they return from their attacks in the town,” he said. “Your goal is to rip out the roots of the rebellion with a minimum loss of life.”

Janós left the same night with five cartographers to gather intelligence and map the area before the main body. They arrived in the hills overlooking Borsod County late in the day. The plains were sprinkled with fiery reflections off thatched cottage roofs and threads of streams. He was home.

Janós arrived at the farmhouse after dark. He’d sent the cartographers to billet at the Miskolc garrison. Katalin and Imre had worked for Janós’s father since he was a baby. They were sitting at the table, bent over their bowls when Janós knocked. A hug from Katalin, a warm handshake from Imre. She had a sixth sense about unexpected guests, and his bowl was on the table in minutes. She understood that his goulash could never have too much paprika; plus he thought her dumplings were confected from air. He had three helpings.

“Is everything all right?” she asked. “You don’t seem yourself.”

“Fine. Fine. No problems,” he said, looking down at the toes of his boots. Katalin knew him too well.

“You’re early this year,” Imre said.

“I’m between assignments so I’ll probably be here longer than usual. You’ll have an extra hand for the harvest.”

“Well, the crop looks good,” Imre said. “I only hope this fighting doesn’t get worse.”

“I’ve heard stories; what’s it about?” Janós asked.

”A collection of things, some small, some large. Last year the governor appropriated ten hectares from the village. People got frustrated. Felt they needed to do something.”

Katalin cut in. “Tell him about Anna.”

Anna: that name, he saw her blonde hair on the hay, felt her tongue teasing him, he never forgot; now, on her hand, another man’s ring.

“You remember, the girl who lived next door?” Imre said. “Her husband was killed by a soldier from the garrison in the spring. Totally unjustified. From what I heard the soldiers started the fight.”

“I lost track of her,” Janós said, struggling to avoid showing his feelings. István, killed? “She moved after I went off to the academy.”

“Over to Sajólád after she got married,” Katalin said.

“Her children, they should be old enough to help on the farm, no?” Janós asked.

“Well, there’s only her daughter, eighteen. Looks like her mother, but has her father’s temper,” Katalin said. “He was always getting into fights.”

Imre said it was shortly after the murder that the rebels started their attacks. They were passionate about replacing the Austrian governor of Borsod County with a Hungarian. Their numbers were increasing as they kept winning.

“They’re becoming legends,” said Katalin. “They seem invincible. In the last four months their worst injury was a broken arm, or at least that’s what I’ve heard.”

“Anna must have relatives though, to help in the fields,” Janós said.

“Not really,” Imre said. “Her brothers went in the army and haven’t been back.”

“You should go see her, Jan,” Katalin said.

“She probably wouldn’t remember me.”

“I saw her at the market a month ago,” Katalin said. “Your name came up.”

“Her cottage is the small one at the west edge of the village,” Imre volunteered. “There’s a stream just to the south of it.”

* * *

Janós remembered this room as a boy, dreaming of galloping cavalry and clashing swords. The white washed walls were covered with pictures, some yellowed now, of soldiers and horses. His father had brought them back. Otherwise it was a simple room, a bed and two wooden chests, one for clothes and the smaller one for books. The memories were comforting, but he couldn’t sleep.

The news of Anna’s husband resurrected feelings he had long tamped down. When he was little, Anna had lived nearby and they’d played on the floor of her parents’ cottage or in their garden. They’d grown older, and school and work in the fields took over, but whenever they’d passed in the lane a sideways glance of her grey eyes and a tilt of her head said you’re-my-friend-come-along-we’ll-play. She and her family were his refuge from an ex-drill sergeant father and a mother who lived in the shadows of the room. Anna was, by turns, soft and warm, quick and fiery; and how she rode! If the wind were a horse she could have ridden it. They chased one another on horseback across the plains, jumping streams and leaping fences. The day before Janós left for military academy, they swam in the river and lay in the sun far from everyone. At the end of that day, they’d made love for the first time, urgently and desperately, promising eternal fidelity. But then, only three months after he’d left, she’d married a farmer, a lout named István. When he’d heard, Janós had been shattered. He became prickly and got into so many fights with his fellow cadets that the commandant threatened to dismiss him from the academy.

Letters to Anna had gone unanswered. On earlier visits back to the village he had ridden out toward her cottage a few times, but was turned back by the thoughts that assailed him: Does she look at her husband with the same glances she gave me? Does she melt into him when he puts his arm around her? Imagining was difficult; seeing would be impossibly wrenching.

Looking back, he knew it was Anna’s marriage that had made him decide on a career in the cavalry. He had more control over what happened to him. Soldiers did things for reasons he understood.

The next morning, Janós rode out to meet the cartographers in the foothills. He showed them how to find the tracks and paths the farmers and herdsmen used to cross the countryside. He was sure these were being used by the rebels. After they rode off, he sat for a moment, looking over the tall grasses, remembering the time he and Anna--they were probably four or five, shorter than the grass, anyway--they’d been playing hide-and-seek. She’d gotten lost trying to find a hiding place and he’d gotten lost looking for her. Her parents finally found them by following the zigzags they’d trampled in the field.

He wheeled his horse towards the southeast. From a hillock he saw the chalk-white walls and thatched roof of a cottage, a stream just south of it; that had to be Anna’s. She came to the door as he rode up. With the sun in her eyes, she could only distinguish a figure on a horse. He saw her hesitate.

“Anna,” he said. “It’s Jan.”

She took a step backward.

“Jan, Janós Hajdú.”

He dismounted and walked towards her, but she seemed trapped in a strange stillness, inspecting him.

As if to absorb the recognition more slowly she paused, and then said, “Come in.”

The contrast with his tenants’ cottage upset him. Imre and Katalin had four rooms; Anna had one. The walls were bare except for some caraway, paprika and bay drying above the fireplace. Fresh wildflowers and three books were on a table in the center of the room. Shiny copper cook pots were beside the fireplace. Bedding was stacked neatly under a bench by the window. Janós saw only four small food baskets. How was she getting by?

She stood at the far side of the table and motioned for him to sit across from her.

“Would you like some tea?” she asked.

“How are you? I hear you have a daughter.”

“The harvest will be good this year,” she said. “We’ll be fine.”

He looked at the woman who had been the girl he loved. The suns of summers in the fields had left fine wrinkles to frame her eyes and mouth. But there was the same light at the corner of her eyes, and her lips were wide and full as he remembered. And he could almost feel the tapping of her tongue when they had kissed.

“Tea would be nice,” he said. “Thank you.”

As Anna put the tea in front of Janós, her hand accidentally brushed his. The touch startled both of them. They sat sipping tea, Janós making appreciative murmurs.

She closed her eyes and took a deep breath, looked up, about to say something. He opened his mouth and blurted, “Anna, I don’t know how to start, for a long time I thought I’d done something or said something, I never heard from you, and three months after I left, you . . .”

She leaned across the table and put her finger on his lips. The touch surprised him, but when he leaned forward, she drew back. Words stumbled out. “My father got sick, my brothers were small, and I couldn’t take care of the farm alone. I had no choice. For years I wanted to tell you.”

Janós felt he needed to say something. “Why didn’t you let me know? I could have come back.”

Her shoulders slumped and she looked tired. “It’s easy to say that now, but your father would never have let you.”

He looked down at his cup. It was true.

Then she told him: István’s stall had been next to hers at the Miskolc market; he had proposed to her every market day from the time they were fourteen; she kept telling him no; he’d get mad, then ask the next week.

“I never told you about any of this. I knew you didn’t like him and I didn’t want to cause trouble. But, with Father sick and you gone . . .”

Janós looked away. “You didn’t write.”

“I thought I’d see you when you came home on leave. I wanted to tell you in person,” she said. “Once or twice I saw you, and I think you saw me, but you rode off in the other direction.”

“But you knew I’d be with Katalin and Imre,” he said.

“I couldn’t go there; István was insanely jealous.”

“Didn’t you get my letters?” he asked.

Anna blushed. “No.”

István.

“Jan, I’m sorry, I should have written.” She reached across the table and took his hands in hers. “You must have been hurt never to have come to see me.”

He nodded and bowed his head, tasting again the old chagrin. He looked up reluctantly, “It wasn’t an easy time.”

They sat quietly with their tea. Janós was trying to reconcile his feelings with what she’d said. To avoid the awkwardness of more silence he asked, “What happened to your husband, how did he . . .”

Behind Janós the cottage door opened and Anna quickly pulled her hands back into her lap.

“Mother, who’s here?”

“Márta, I’d like you to meet my old friend Janós Hajdú; we grew up next door to one another. He’s in the Cavalry now. Jan, this is my daughter, Márta.”

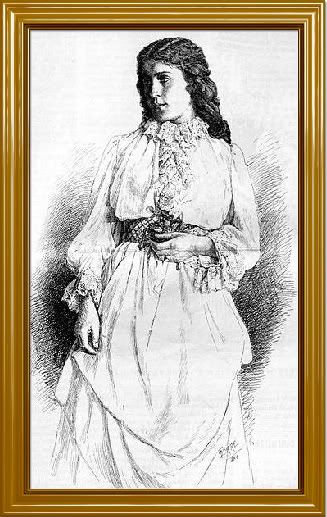

Márta was Anna at eighteen: tall, blond, and grey-eyed, in a bloused white shirt and pants tucked into soft black boots. This was the image of Anna he carried from that last day they were together. Janós could feel his face getting red.

Márta turned to leave, but Anna took her arm. “Sit down. Please pour us another cup of tea, and one for yourself.”

Márta served the tea, but sat on the bench near the wall, folding her arms tightly across her chest.

“I was about to tell Jan what happened to your father,” Anna said.

“I’ll tell him,” Marta said. “A friend of mine saw everything.”

She swung around in her chair and looked directly at him. “My father and his friends were in a bar in Miskolc. A bunch of Austrian soldiers called them Jews and Gypsies, knocked over their glasses. My father didn’t put up with that sort of thing. He and his friends pushed the soldiers away. Then one of them punched my father in the mouth and everyone started fighting. All of a sudden one of the soldiers pulled out a gun and shot my father. Murder. And the garrison commander did nothing.”

Janós reached over toward Márta. “I’ll talk to him.”

She pulled back. “What’s the use? It’s over now. I don’t want to have anything to do with soldiers,” she said. “So why are you here?”

With two Annas in front of him and wanting both of them to like him, he lied. He explained that he came back at harvest time nearly every year to see his tenants and help bring in the wheat.

“Why should I believe you?” Márta asked.

He said nothing. And then as the sun shifted into Janós’s eyes and he realized how long he had been there. He mumbled an excuse about seeing someone else and stood up. Anna walked outside with him.

“Excuse her, Jan. Sometimes she becomes very bitter about what happened,” she said. “Will I see you again?” She touched his hand.

He replied with a smile.

Janós rode away slowly. There was a time he hadn’t wanted to see her; now, he found her beautiful in a new way: a restive, suffused glow had replaced her shimmering exuberance.

* * *

Janós and the cartographers rode out to check their maps. After an hour they split up. He wanted to scout the routes from the mountains into the plains for the soldiers who would be arriving. First he rode to Anna’s cottage. She came to the door; he guessed she’d heard his horse.

“I came by to see if you wanted to take a ride in the mountains.”

“I’d like that; it’ll be like old times,” she said. “Do you want me to pack some food?”

Janós pointed to his saddle bags. “I’ve got enough for the two of us.”

“So you presumed, did you?”

The tone of her quip was somewhere between coquetry and annoyance. He couldn’t read her intentions the way he once had.

“No, but I had hopes,” he replied.

She smiled.

They rode through old beech forests and grassy meadows of violet-blue gentian and yellow yarrow. Eagles and falcons wheeled lazily on the high currents. Anna found a bough-sheltered alcove by a brook. As they ate and talked, she became his memory: her mouth tilted up in the corner; she brushed her hair behind her left ear, always her left ear, even as it fell across both eyes. He didn’t talk much, thinking that tales of his battles or stories about his missions in Paris and Vienna would seem out of place.

She was full of stories about Márta. She’d weighed only two kilos when she was born and Anna had worried. But as a young girl Márta had shown a fierceness and determination that made up for her size. When she was four she’d take a book from the shelf, shove it in her mother’s hand and command, “Read.” She lost none of her fire as she grew. Even boys her age wouldn’t go up against her.

Anna began to look wistful, her eyes half closed. “I didn’t have more children,” she said. “So I let Márta have her own way, maybe too often. But she can read, write, ride, herd, and farm. I made sure of that.”

During a lull in the conversation, Janós stretched out on the ground and closed his eyes, seeing himself with Anna, raising a daughter; he, not István. Janós was pleased she hadn’t mentioned him.

Anna began to lie back.

“I think I’m softer,” he said. And guided her on top of him.

Back at the cottage, he was awkward helping her down from her horse. He shuffled his feet and stammered. She made it easy: looked up, kissed him quickly and said, “I’ll see you again.”

At that moment the sun seemed to enclose only them in its fading glow.

Janós rode out to meet up with his squadrons in the mountains. Five hundred soldiers in peasant clothes. Horses stripped of military accoutrement. It was dusk when he addressed them.

“Every evening you will move out of the mountains. You have your maps. You will be on every path a rebel could use. Find him. Capture him. Return before dawn.”

The soldiers trickled out of the mountains into hornbeam and oak covered knolls, behind grassy hillocks, and into the sandy stream beds below Miskolc. Two nights later, four rebel bands attacked government buildings and the garrison in town. As they returned to their homes, soldiers sprung from hiding places. Fifty rebels were captured and taken to the stockade in the mountains.

The next night was quiet, and the next night, and the next. Janós knew the rebels might think they could hold off until the soldiers got tired of waiting and went back to Buda, but he had prepared for this: extra rations and the promise of extended leave when the campaign was over.

Seven rebel attacks. No one was killed, but ten soldiers were wounded and three captured. Seventy rebels were captured, but none would divulge the names of their leaders. Then two weeks with only sporadic small eruptions. Janós understood the need for patience but circumstances were beginning to wear on him. To maintain the fiction that he was unaffiliated with the military campaign, he had supper with Katalin and Imre every night, listening to them talk in great detail about bloat, foot rot, milk fever, and sweet clover poisoning.

When he received a dispatch from General Bauer reminding him that “Do this quickly” was part of the orders, Janós replied in a tone that indicated Bauer’s dispatch was unnecessary, and unwarranted. He reminded Bauer that the plan the General had sanctioned was working well, and the results were as expected: no one had been killed, the stockade was nearly full. If the villagers wanted enough men to bring in the harvest, they would be forced to turn in the rebel leaders and that would be the end of the rebellion.

Janós knocked at Anna’s door; it flew open and Márta stormed out, yelling back, “Your soldier is here,” and shoved past him.

“Maybe I should go,” he said.

“No, stay; we were only having an argument about the harvest.”

She led him to the small bench, sat close and took his arm.

“I’ve been thinking about things, about you, about us,” she said. “It’s been a very long time, and lot has happened with both of us, but these last days . . .”

Janós interrupted, “I’ve been thinking too; Anna, would you, will you . . . come back with me to Buda, be my wife?”

She smiled and lowered her eyes, “Yes, I . . .”

The door crashed open. Márta stormed in, flushed. “Mother, did you know he was leading the army here? Our neighbors are rotting in a mountain stockade because of him.”

Anna stood with a start--her anger adding to her height.

“Márta! You can’t come in here and level accusations like that. Apologize.”

“I won’t,” she said, turned, and slammed the door.

Anna wheeled on Janós. “You’re in charge and you haven’t told me. This is your idea of relaxation: locking up people who are fighting for their rights.”

“I couldn’t. I haven’t told anyone, not even Katalin and Imre. I couldn’t,” he repeated. “It had to be done this way. But I promise; it will end soon.”

“That’s not what I am talking about. After all these years you come to my home,” she said. “Like a fool I thought it was because of me.”

She backed against the wall, putting as much distance as possible between them.

“Did you think about me? Being seen with an officer in the Austrian army while this was going on. I’ve told everyone you’re the same person I grew up with: someone they can trust. Now this.”

Janós took a step toward her, head hung down.

“I’m sorry. I should have said something. I’ve never forgotten you; that’s why I came. Can’t you forgive me?”

She reached up, put her hands on his shoulders and pushed him down in a chair, then drew another up in front of him. Her eyes were defiant and her mouth was a thin white line.

“Something I haven’t told anyone. Márta is our daughter, yours and mine. I got married so she’d have a father. I didn’t tell you before because it didn’t make a difference: to us, or to her.”

Janós felt the walls close in on him, he was hot, the sun was sitting on him, he heard his blood moving through his head, racing his thoughts, then stopping them; Anna’s face was shrouded in light, then distorted by closeness. He kneeled and put his arms around her.

“I have missed so much: you, being with you, having a family.”

Minutes passed before either of them breathed. Then she took his head in her hands and bent her face to his. She threatened, “Be careful, be very careful. Our daughter is one of the rebels. You must absolutely make sure nothing happens to her.”

“I promise; she will be safe,” he said. “On my life.”

* * *

A delegation of farmers came up to the encampment in the mountains. “Colonel, you’re a son of the land, you know we start the harvest in two days. You’re holding nearly two hundred of our most able men.”

“Bring me the leaders of this rebellion and I’ll release the men in the stockade.”

“But Colonel, we don’t know who they are.”

Janós’s face displayed incredulity; his voice, steel. “That surprises me, but I’m confident you’ll find out. Come back when you have them.”

After the farmers left, Janós spat out orders: “Prepare for an attack on the stockade. Triple the guards. Post men along the mountain paths.”

That evening the rebels were allowed to come up the mountains to the stockade. They fell back in disarray when met by the reinforcements. Scrambling back down dark paths, the rebels were easily picked up by waiting soldiers. Another hundred were captured with few injuries to either side. The stockade was jammed.

Within an hour the delegation of farmers was back with five men in ropes trailing them. In the light of the camp fires Janós saw the rebel leaders ranged from grizzled farmers to young men. He thought he recognized an acquaintance from twenty years back and quickly turned to avoid eye contact.

“These are the five? There are no more? You are sure?”

“Yes sir, we are sure,” the delegation chorused.

“If you are wrong, you will never worry about a harvest again.”

Janós stood back, crossed his arms, and ordered the men in the stockade released. Then went into his tent. He’d send the five to Buda. General Bauer dealt with traitors. They’d be put in front of a firing squad.

An aide opened the tent flap. “Your orders, colonel?”

“The prisoners leave for Buda tonight. I do not want anyone trying to rescue them. I will question them when they are tied and mounted.”

Janós came out of his tent and saw the rebel leaders being bound and put on their horses. It was a routine procedure: the prisoner’s wrists were tied, two soldiers hoisted the prisoner into the saddle, his hands were lashed to the back of the saddle, and feet were tied into the stirrups. The last one was being lifted into the saddle when the prisoner spurred the horse. It broke away and galloped into the trees. To Janós’s left, soldiers shouldered their rifles. His “No!” was drowned by the bark of the bullets.

The rider’s cap fell off as the horse passed under a branch. Long blond hair spilled out. Twenty years earlier, the same streaming hair he had chased across the fields.

He saw the bullets spinning out from the rifle barrels, moving towards her, arrows of fire. He heard thuds as three hit the trees. He saw two others pierce her blue linen jacket, tear her flesh and enter her back. Her body writhed from the impact. She tumbled from the saddle, scrambled awkwardly for a few yards, and then lay face down on the ground. Janós ran, pushing his way through the soldiers. He cut away the ropes and slowly turned her over; a large dark stain covered her chest. He drew the hair away from her eyes and cradled her in his arms. Her cheeks were cut and bruised. He carefully brushed the dirt from her face.

“Márta,” he whispered. “Márta.”

She opened her eyes, recognized Janós, and her pupils narrowed to pinpoints of hatred, a look so black and feral he turned away. Soldiers crowded around them. They looked dumbfounded, anxious, and disconcerted by what they were seeing. He looked back to Márta. In that short space of time her face had gone slack, the fire in her eyes had gone out, and blood burbled from between her lips.

Janós slumped. He saw the shape of Anna standing in front of him; he was kneeling in front of her. In the cottage that afternoon: “Marry me?” “Yes.” “She will be safe?” “I promise.” The vision twisted, broke apart, then faded into the night. Lost, lost forever.

Janós picked up Márta and called for his horse.

“I’m taking her to her mother.”

He rode slowly out of the mountains towards Anna’s cottage, his daughter in his arms. Knowing: there was no explanation, no reason, nothing he could say.

A light from Anna’s cottage shone through the starless night. She’s been waiting for Márta, Janós thought. He kneeled his horse in the shadows and carried the body to the cottage. The door was open.

He called, “Anna. Anna.”

No response. He went inside and laid Márta on the table, carefully arranging her hair. Outside, he heard Anna call.

“Márta, is that you? I’ve been out looking; where have you been?”

She came inside, saw her daughter’s colorless corpse, buried her head in her bloodied chest, and wailed, oblivious to Janós. Minutes passed; she became very quiet, and then turned on him.

“You promised! You promised!”

“She was trying to escape; I didn’t know; no one knew it was her.”

“On your life, you said.”

“It was a horrible, horrible accident; I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

They kept vigil through the night, saying nothing, their daughter lying on the table between them. At daybreak, Anna moved to the window where Janós stood, watching the wheat molding in the heavy rain.

“Look at me, me,” she cried. “You’ve emptied me, emptied me out. I’m a shell.”

She put her face in her hands, sobbed, then an eerie stillness seemed to come over her. She lifted her head and in a small haunted voice said, “I will go to Buda; I will marry you. I will be there to watch you empty out, to wither and crumble, to atone for what you have done.”

He looked into eyes that once held the promise of love, but saw nothing; they had separated from her soul. He took her hand, but there was no warmth in her touch.

* * *

Townsend Walker lives in San Francisco . During a career in finance he published three books: on foreign exchange, on derivatives, and the last one on portfolio management. Four years ago he went to Rome and started writing fiction inspired by cemeteries, foreign lands, paintings, and strong women. His stories have been published in over two dozen literary journals, on-line and print.

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?

The attraction of historical fiction: it is an interesting and entertaining way to learn about history and society. It gives color and texture to the dryness of text books. Hardy has a lot to say about 19th century English society; Dumas is a grand historian with his tales of the French nobility.

0 comments:

Post a Comment