The Last Arrow

translated by G. K. Werner

Translator's Note: The excerpt from the Clerk of Copmanhurst letters published here as “The Last Arrow” was long dismissed as a Renaissance hoax, a reworking of “Robin Hood’s Death” and the last six stanzas of “A Gest of Robyn Hode”. We are indebted to literary historian Sir Clee Pearson whose Sherwood Tales: The Clerk of Copmanhurst Letters, Annotated (Halifax: Furness and Sons, 2007) has so ably demonstrated the Clerk’s veracity and his letters’ authenticity. In addition, I am indebted to my very own Marian, Virginia Ann Werner, whose editorial eye matches Robin’s arrows for the mark, and whose ear for the perfect word and phrase rivals the Clerk himself. I have not tampered with the Clerk's history beyond translating his late Old English into modern short story form, convinced that the people of history must tell their story unhindered by the present generation's biases. – GKW, Seaford, 2010

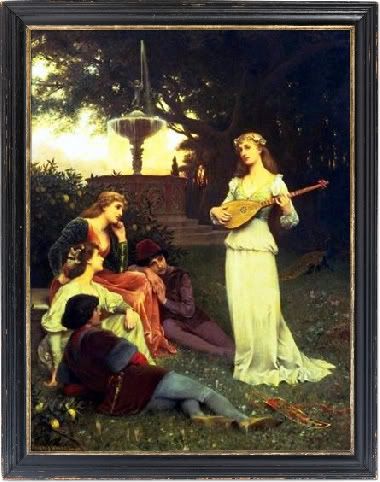

From the Clerk of Copmanhurst’s final letter: The crowd gathers one last time ‘neath the shade of Sherwood’s Great Oak. No laughter or jesting or jostling this day. The Minstrel strums his lute, a lively tune, counterpoint to his theme. And here I tarry yet a little while, bent over my tree-stump desk. My quill takes wing to pace our minstrel’s tale, recording its final hour.

The Minstrel sings:

Come list fair ladies, yeomen too,

The truth may now be told,

A tale of Robin’s darey do,

A tale of John so bold.

The Devil's prioress made Rob’s bed,

Up in her tower, cold,

And Robin’s goose-fletched arrow sped,

A hey down down false-play.

No tale for squeamish, skittish faint,

No minstrel’s lie retold,

The Friar writes, the Minstrel sings,

The death of Robin Hood.

The Tale:

Robin had lived a full life and a merry. He had seen tragedy and triumph, cruelty and kindness, oppression and the freedom of a forest in May. Lived to see his grandchildren nock arrow to bow, and lived to see their freedom birthed at Runnymeade where a hard-pressed and reluctant King signed the Great Charter. He had outlived great enemies, friends as well, and knew his own time to be short, the aches and pains of advanced years compounding the nuisance of old wounds. But death would not find Robin resentful or a-begging. He had never lacked for adventures, and having made new enemies (Robin being as intolerant as ever of arrogance and injustice), a good death and a swift was almost a thing to be desired. A last adventure! A final jape!

Kirklees, October, 1236

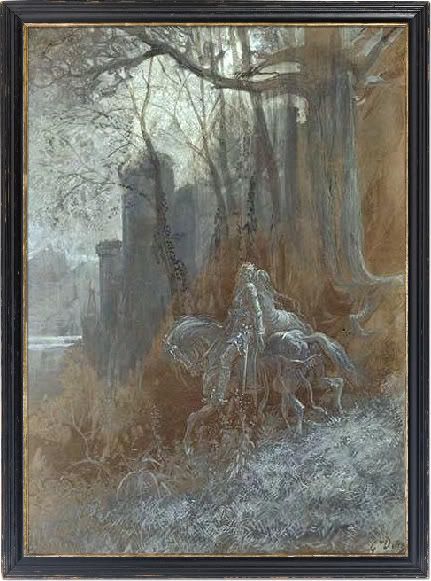

The nuns watched in superstitious dread, hands to hearts and mouths, as the giant came down out of the forest in the fading light, a limp form cradled against his massive chest like a beloved rag doll. He made for their nunnery, a crumbling and barren place, its gatehouse, hall and tower in the midst of an ill kempt, weed entangled estate. Despite his burden, he grasped the iron ring on Kirklees gate and knocked thrice loudly, scattering the nuns on the other side of the door.

Beckoned by her gaggle’s honking, the prioress came and squinted through the gate’s portal. A man with a child in his arms? Nay—a giant with a man in his arms! She peered closer, hardly believing what the torchlight revealed. Her worst enemies—at her very door! Little John carrying Robin Hood, their longbows at his back? Coming to her for physicking? It had to be a trick. She peered closer still, noted the giant's watery eyes and the fever-damp form in his arms blotched by blister-red and pox-white. Her eyesight was not so good as it used to be, but her great enemy certainly did not look well by torchlight.

“A boon!” cried the giant. “A boon in the name of God, I beseech you…” and he swayed like an oak in the wind before her door, Hood’s green-clad body still as death in his arms.

“This is a nunnery,’ she called through the little window in the gate. “We are nuns in here, devoted to our master and do not traffic with outlaws.”

“He's dying. My friend is dying. Oh save him, Lady Prioress. We are honest outlaws. Work your priestly art and heal him. I beg you. As you love the Lord our great physician.”

Phah! The Lord of the Cross is not my lord, she wanted to shout. Never had been! She'd served another faithfully all her life and the Lord of the Cross no longer dwelt within these walls. Had her true master rewarded her with the prize of a lifetime? She would be eternally grateful.

“This bag at my side contains twenty pounds in gold,” said Little John, his voice breaking now. “He bade me give it you for a cure. 'Spend it freely while it lasts,' he said, 'and you can have more when you want it.'”

“Show me the gold,” she called through the portal.

John kneeled to balance Hood on a raised knee, opened the bag on his belt, and hefted it with a resounding jingle-jangle.

The prioress smiled tightly. She clutched the dagger she always kept beneath her robes and signaled to a nun who had crept back to her side and now creaked the door open to admit them.

Beneath his burden, the giant staggered to his feet, through the gateway, and into the courtyard beyond. He ignored her nuns encircling him at a cautious distance, and gazed innocently into the prioress’ eyes.

She returned his gaze with finely arched brows. Did he not recognize her? Had the young seductress he once knew changed that markedly? The years had not been kind to Mother Maudlin, Prioress of Kirklees—she who had once been Isambart de Belame’s wife, the Lady of Evil Hold, and Sir Roger of Doncaster's lover. Red Roger! Her lover. Dead at Robin Hood's hands! Dead these many dry years.

Deftly, she clawed the bag off his belt, weighed it in one talon while the other delved deep. Twenty pounds of gold brought a warm glow to the prioress's pallid face. “Stay,” she croaked, crooking a finger at John.

She flew into the gatehouse, black robes flapping like happy bat-wings. Inside, she hid the bag in a secret place behind a loose stone, and returned to the courtyard.

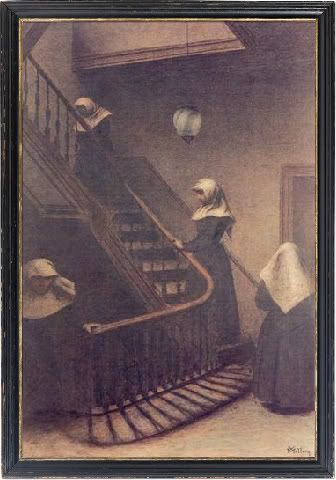

“Bring him,” she ordered the giant, and, gathering her dark robes above her feet, led the way, torch in hand, across the courtyard toward the ancient bell tower of a ruined church. Her nuns followed, whispering among themselves, eyeing the giant and his friend.

Within the tower, a winding stair rose into darkness. The steps were cracked in places, littered with debris and covered in thick, undisturbed dust. An industrious spider’s great cobweb barred the landing’s wooden frame.

“Mother?” a nun exclaimed, shrinking back at sight of the web.

“Fetch my satchel,” the prioress snapped at her. Then turning to Little John, “Take him up,” she ordered. “The rest of you, wait here.”

John plowed through the web and started up. Slowly they ascended the worn steps, John in the lead, the torch-bearing prioress at his back protected from mishap by his weight. If a step gave way, it would be the giant's death and Hood's, not hers.

The square tower was tall and old, built soon after the Conquest as a refuge for the nuns. It had not been maintained. Cracks had been left to widen as mortar disintegrated, and holes gaped where stones had fallen out entirely.

Little John trudged on, up and up the steps, gently carrying his precious burden, draped by the giant cobweb from face to boot.

The prioress had not been up this winding stair since her days as a novice. So many years in the past! She had come to hide in Kirklees soon after Hood and his murderous band of outlaws burned Evil Hold to the ground, killing Isambart and her beloved Roger. She had sworn vengeance, but after many failed attempts on Hood's life, had given up hope of ever drinking its sweet wine. Till now!

She fingered a key hanging with others from her black-velvet belt, hoping it would still work the lock up there. The door probably stood open, but she’d not have her prisoner wandering off in a fever, killing himself by chance on the steps before she worked her ‘cure’. Afterward . . . well, there'd be no afterward for her hated foe.

They reached the top of the stair and John stumbled over the threshold into a small square room with a narrow window at the center of each wall. A rough-hewn bed, a chamber pot and a low table were the only furnishings. A puddled candle, broken trencher, rusted knife and prayer-beads littered the table. A moldy rope hung through the opening in the ceiling. The broken bell lay on its side in a dusty corner.

“Set him there.” The prioress pointed a long-nailed finger at the tattered mattress bristling with straw like a porcupine.

John smoothed the mattress in the sweeping motion with which he lay Hood down. He wiped and plucked the cobweb strands first from his friend's face and Lincoln-green tunic, then from his own.

The prioress thrust her torch into a sconce above the bed and peered down at her patient, a vulture considering her next meal.

“He hasn't eaten in days,” said John forlornly. “Can't keep anything down when he does.”

She poked Hood in the ribs by way of commencing her examination. “Skinny as a bow-string,” she confirmed, but had no way of knowing whether from old age or disease. He didn't look good in the flickering torchlight. That was certain. White as sifted flour and blotched as a pocky villein!

“We must bleed him, of course,” she said, “to remove the vile humours.” And, as if on cue, a nun arrived with Maudlin’s heavy cloth satchel. She laid it on the table, then fled.

The prioress removed a set of silk wrapped blood irons and selected one. The slim steel flashed in the torchlight.

“Roll up his sleeve,” she ordered Little John. “And set that pot 'neath his elbow.”

John hesitated.

“If he is not bled, and that at once, he will surely die.”

John eyed her blood iron with loathing.

“An unwise man is he who heeds no warning,” she rasped, fetching the chamber pot herself and setting it under Hood's elbow. She hitched up his sleeve and laid the blood iron to the bend of his arm.

“NO!” cried John as, with a sudden swift thrust, she pierced a blue vein. Hood jumped in his skin, much to her satisfaction, and his full red blood fountained.

“What have you done?” roared John, advancing on her. “Oh, what have you done?”

“That which must be done and nothing more.”

John reared over her, glowering like a bear.

“Peace, outlaw. The evil humours must drain away if his health is to be restored. You begged a cure. This is it. A procedure recognized by scholars and physicians both here and on the continent. The four bodily fluids must be properly balanced. What know you of leech-craft?”

John relented.

Hood's blood ran pleasantly thick and long as night besieged the tower. Moments oozed by like snails.

John fretted.

The prioress felt for her key.

The blood in the pot below Hood's open vein rose higher and higher. A sound like rain on stone echoed in the stillness.

Suddenly, Hood sat bolt upright, reaching for her. Nimbly, she sprang back. “Treason!” he cried. “John! We are betrayed.”

John sprang to his side and grasped Hood's arm in his big paw, stanching the flow of blood. “Robin!” he wailed. “We are undone. Kirklees will be your deathbed in very truth.”

“Be still,” Hood hissed, weakly clutching at John's sleeve. His eyes rolled back in his head and he went heavy against John's arm.

“Robin! Robin!”

The door slammed at John’s back. The lock clanked shut.

The prioress lurked halfway down the spiral stair, listening for death to claim her foe. Hand on dank wall she craned her neck to hear what she might. A wail of woe from the giant? A dying curse from Hood? Whatever pleasure she might steal at the end!

The bell tower's silence mocked her.

She couldn't stomach it, the suspense of not knowing. Heart in mouth she took a step up, then another, and another, up and up till, before she knew it, she was back at the bolted door stooped like an old crow with cocked head, her black-pupiled eye peering through the key hole of the tower's high, torch-lit chamber.

Little John sat on the bed where Robin Hood lay with a blood soaked strip from the sheet tied at his elbow. “I must have the last rites, friend John. Let me not die unconfessed.”

The prioress could hardly believe her ears. Hood's reputation was that of a heretic following the teachings of an excommunicated priest named Tuck.

“I’ll not have you confessed by the likes of this evil prioress,” John growled. “The rotten prune. The mothy bag! The cankered worm! The foul she-fiend! She’s like to send you down the other way.”

She heard Hood’s ragged choke, but could not tell if it were a death rattle or a laugh at her expense. Little did it matter, she thought to herself. Soon enough, my master'll give you a fair greeting.

“A boon, Robin,” the giant sobbed. “Ahhhh! Grant me a boon, noble master. I beg thee.”—his voice, a strangled cry.

“What is thy boon,” asked Robin Hood. “What boon dost thou beg of me?”

Mellow-dramatic fools! Did they think death a play to be performed?

“Give me leave to fire this tower, to burn all Kirklees to the ground. A funeral pyre of vengeance.”

The fear that spread its icy flame across her back was quenched by Hood's next words.

“That I will not,” he said, over-gently. “For it may not be. Ne'er in my life have I hurt fair maid.” John choked—a sob? “And neither shall it be at my end. 'Vengeance is mine', sayeth the Lord. Let us not trespass on his grace. But string my bow and give it me, and an arrow straight and true. Ah! My thanks, faithful John! Now brace me as I shoot.”

The giant lifted Hood to a sitting position, placed the bow in his hand and helped him nock arrow to string. Hood’s bow arm wavered. His arrow-point drifted this way and that – then locked on the keyhole.

The prioress flung herself back, narrowly avoided a plummet down the stairwell. She leaned shakily on the rail. Now she felt silly. Hood’s old ears could hardly have detected her presence, and bowman that he was he couldn’t pass a broad-arrow through a keyhole. She darted back to the door and again peered into the room, though not without some trepidation.

Hood was leaning back against the giant’s chest, his arrow now aimed at the east window through which the forest could be glimpsed away to the east, a darker crest against star-lit night. The prioress savored the giant’s great wracking sobs, though she could not see his anguished tears.

“Where this arrow lands,” Hood told him, “dig me my grave and bury me in the good greenwood with a verdant sod for my pillow, my stout yew bow at my side and my arrows at my feet.”

Hood’s arrow leapt through the narrow window. John howled like a wolf bereft of its brother. The shaft arced forest-ward into darkness, keening like a lost soul.

With a deep moan, Hood went limp in his friend's arms.

John howled once more, a blood-curdling howl, a banshee's hellish wail. Gently, he lowered Hood’s body, straightened it out on the mattress. Then rose and threw himself against the door.

The prioress turned and fled down the spiral stair, down and down and down, stumbling in the dark. She missed a step to land hard upon the next. Then stepped out into nothingness.

At the foot of the steps, the nuns heard her scream and heard her body thud once, twice, thrice as she bounced to a stop at their torch-lit feet.

They stared at her in stunned silence. “Is she dead?” hung in the air, but no one dared mouth it. “Shall we summon the Master to save her?” a novice asked, and another rolled her eyes.

The prioress stirred. The merest flicker of an eyelash, and the sisters shrank back, watching, waiting. Amazingly, she crooked an arm, pressed palm to floor, then a leg, the other arm, another leg, elbows and knees all akimbo, unfolding herself like a giant black spider.

A crashing whine of metal in the darkness above their heads told them that the giant had smashed the chamber-door off its hinges. The nuns fled, the prioress scuttling along behind as best she could, fleeing pell-mell through the hall and spilling out into the courtyard.

Little John strode out the tower door, carrying the limp, death-white form of his beloved friend. He crossed the moon-lit courtyard to the gatehouse, paused to glare back at the nuns cowering against the farthest wall. The prioress straightened to meet his glare, fists on hips, defiant to the last.

“Witch! I should hang you from your own tower,” he growled. “And burn this godless priory to the ground. But, against my better judgment, I shall honor this godly man's last request and spare your miserable lives.”

And, with that, he strode off through the gate toward the greenwood, following the path of Robin's arrow.

The Great Oak, Sherwood Forest, 1242

The Minstrel's song ends on a discordant note.

The crowd winces as one.

His voice is almost a whisper. “Legend has it Little John found the arrow in a peaceful forest glade, lodged in grassy turf, and that there, ‘neath the shade of a Sherwood oak such as this, he buried his truest friend, Robin’s grave, nestled in the heart of his beloved greenwood.” There are tears in the Minstrel's eyes now. Tears of sorrow and loss? How alike are the body’s reactions to grief and glee.

The crowd begins to realize—shockingly, the Minstrel is laughing so hard he is crying. “Quite a remarkable shot,” he says, “even for Robin Hood, when one considers that Sherwood lies more than forty miles south of Kirklees Nunnery, Yorkshire. Ah, but hold! Robin Hood graves in northern England are thicker than fleas on an old dog. Praps he hit a closer one.”

This is too much! The crowd gapes at him in wonder, hardly crediting their ears. Is he ridiculing their hero's tale? The well-known and beloved tale? Ridiculing Robin himself?

“And, have any of you ever wondered how John managed to find Robin's arrow? In a forest? Robin must have rotted to dust while John searched for the proverbial needle in a—”

The outraged crowd shouts him down. How dare he make light of a brave man's death? Their hero! Had not the Minstrel himself been one of Robin's closest and dearest companions? “You ought to be ashamed of yourself,” they scold. “She killed ‘im. Just like that. The wicked prioress killed our Robin and you 'ave the gall to mock ‘is death?”

The Minstrel finds this all the more amusing.

The crowd grows quiet, thoughtful. “She did kill 'im,” somebody says—Robin Hood, after all, having been Robin Hood. “Didn't she?”

“Very nearly she did,” the Minstrel replies, controlling himself at last and with great effort. “Aye, thanks to her blood iron, he was at death's door that night in Kirklees' tower, and no mistake. But Robin and John, old as they were, could still think fast in a pinch. Always had! Even in the tightest of pinches!”

“You mean—”

“His enemies were relentless, younger replacing older, proliferating like flies on a dunghill. They wanted him dead. So why not be dead? He and Marian deserved a rest, peace in their final years. We all did!

“Their plan was a good one. Village gossip wouldn't do. For his enemies to believe Robin's death, an enemy must witness it. Conveniently, Maudlin had burrowed into nearby Kirklees. Marian contributed the onion for John's tears and the plum juice for Robin's fever-ravished complexion, Much the flour for a convincingly white corpse. A jolly good plan! Just like the old days. And it worked too, despite the prioress' unexpectedly swift stab at vengeance. Ironically, Will had suggested Maudlin as their least deadly enemy and Kirklees as the safest place to perform their play, ‘The Death of Robin Hood’. Sherwood shook with merry laughter when Robin and John returned to tell their tale.”

And now also, as the crowd hears the truth for the first time. Uproarious laughter. Robin the Fox! All these years! And minstrels spreading the tale of his death far and wide. They wink and elbow each other in the ribs and slap one another on the back and hold their sides and bellies till they ache and some fall down.

A simple-hearted folk! Robin had loved them dearly.

With all the merry band now gone,

Save only Tuck and me,

The merry jape is told at last,

Twas saved for such as thee.

* * *

G K Werner is a high school and college English, history and martial arts teacher who writes genre fiction from a Biblical perspective. His stories have appeared in Tower of Ivory, The Sword Review and Fear and Trembling. He lives in 'slower lower' Delaware with his wife, home-maker, gourmet chef, poet, songwriter and published author Virginia Ann Werner (who taught him the storytelling art); their collie, Skipper, and four cats (who don't write, but have strong opinions).

Where do you get your ideas for your stories?

I never missed an episode of Richard Greene's Robin Hood while growing up in the fifties. Henry Gilbert's Robin Hood and the Men of the Greenwood was the first full-length chapter book I ever read. I didn't get the part of Robin in a sixth grade play, but always starred as Robin playing in the woods with friends (and kept the merry man costume my mother made for me as a bit player). My English relatives (the Pearsons and Clees) showed me Nottingham, Sherwood Forest (what's left of it) and Yorkshire (the original Robin Hood territory). I stood inside the Major Oak (probably a sapling in Robin's day) and have long steeped myself in Plantagenet England. OK, I'm a Robin Hood nut! So what do you do when your favorite show is off the air and you've outgrown your Robin Hood costume and playing in the woods with homemade bows is frowned on by adults? You write Robin Hood tales. (Oh, and I hate sad endings -- Romeo and Juliet were pinheads!)

0 comments:

Post a Comment