In the spring of 1843, Bronson Alcott, the father of Louisa May Alcott, and Charles Lane established the Utopian community of Fruitlands in Harvard, Massachusetts. Here is an excerpt of the publicity notice they published about their commune:"We have made arrangements with the proprietor of an estate of about a hundred acres which liberates this tract from human ownership. Here we shall prosecute our effort to initiate a Family in harmony with the primitive instincts of man.

"Ordinary secular farming is not our object…Consecrated to human freedom, the land awaits the sober culture of devoted men. Beginning with small pecuniary means, this enterprise must be rooted in a reliance on the succors of an ever-bounteous Providence, whose vital affinities being secured by this union with uncorrupted field and unworldly persons, the cares and injuries of a life of gain are avoided.

"Pledged to the spirit alone, the founders anticipate no hasty or numerous addition to their numbers. The kingdom of peace is entered only through the gates of self-denial; and felicity is the test and the reward of loyalty to the unswerving law of Love." (Quoted in Louisa May Alcott’s “Transcendental Wild Oats)

The Prodigal Son,

or, the diary of William “Adam” Merrill

by Alex Myers

June 6, 1843

Departed from my father’s farm this morning—bright and sunny, which augurs well—and after crossing the Merrimack River, arrived early evening in Dunstable to stay this night with my aunt and uncle. Though they are generous to offer me bed and board, here too I found my purpose—even my character!—questioned and ridiculed. At supper my aunt placed cow flesh before me to eat, which I pleasantly declined, explaining to them the virtues of a vegetable diet. My uncle could barely contain his mirth—as a doctor he considers himself a foremost scientist and thinker—in explaining that man cannot be sustained by vegetables alone, he requires milk and meat to make bones. But, I protested, horses and cows, which eat naught but grasses and grains, do fine making their own sturdy bones. To this, my uncle had no reply but to call me a haughty young fool. The rest of the meal was held in silence, which I found preferable.

Tomorrow will be the start of a new episode—of my new life, I might say—I will finally be free to think and speak, to be more than a mean toiler, slaving away for foul profit. I have the chance to begin again, with like-minded people. Consociate. Even the word sounds pleasing, right. As soulful as Transcendentalism, the fount from which the consociates sprung. By tomorrow eve I shall have arrived at the new community, Fruitlands, the second Eden, to live as man is meant to live. The journey should be swift—as today’s was—for what do I need to carry? A cup to drink from streams, a few sundry books with which I could not part. My spirit shall sustain me as I embark upon the life I—and all true men—were meant to lead.

June 7

It is better than I even thought. Eden indeed! Catching a ride with a local farmer who was hauling wood along the same road, I arrived at Fruitlands in the heat of mid-afternoon. I was happy for the expediency of the ox-cart to take me to my Promised Land, but glad to know that this will be the last time I ever use an animal for such a purpose. Here is life as God—and Nature—intended it: humans obtaining just what we need from the Earth, with nothing in excess and neither harming nor taking advantage of any living thing.

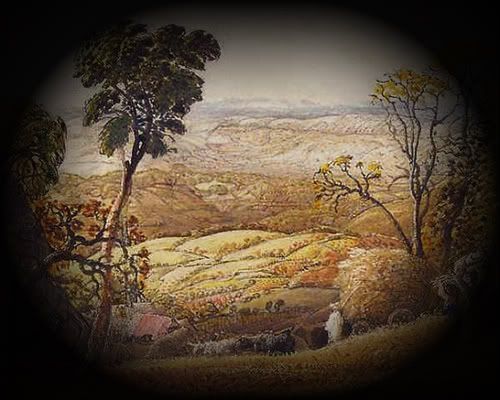

There is a barn and a house set amongst rolling fields with a few patches of woods and orchards. The two founders, Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane, have taken up residency in the farmhouse; Bronson’s brood of daughters sleeps in the attic and the adults occupy the second floor. The ground floor is common space, a kitchen, a dining room, and a parlor that has been turned into a school room for the children. I peered in when I arrived and spied not a few volumes on the shelves—along with a bust of Socrates!—and I am already looking forward to an evening when I might sample their contents. As for me, I am bunked in the barn—having liberated the animals from their labor, we have taken their stalls, their straw-lined former prisons, as our own. Next to me is Brother Joseph, whose beard grows quite to his knees; he was sleeping when I arrived and did not attend supper, where I ate with Bronson and his daughters, sharing the last of the bread I brought with me, and a bean soup his wife had made. There are others soon to arrive, and I can scarcely wait to meet the rest of my brethren on the morrow.

June 8

The dawn greeted me with rose-hued splendor this morning. I crept out from my stall, for Brother Joseph was asleep (indeed, he did not rise until almost noon!), and walked the perimeter of the fields, basking in the dawn light and the miracle of being here. Father was loathe to let me go, claiming he needed my labor at the farm. But I told him I did not need the labor, nor a place at his table, nor his roof over my head. And so I do not. Indeed, I am learning here how little I do need to be content. Before, I had only read the transcendental philosophy in such papers and books as I could get my hands on, but now I have a chance to live it fully. So I shall!

For breakfast I drank my fill of cool water and ate a plain corn cake. The Alcott daughters, free from lessons in the morning, took me around the farm, showing me their pet duck—fearless, for it knows no one shall eat it—their favorite spot by the creek, and the best apple tree to climb. Noontime brought the arrival of another new recruit, this one named Isaac, who had lately resided at Brook Farm, but found that consociate community to be too frivolous and materialistic. I sense already a great connection to him. Charles, one of the founders, also returned from an errand, and so our supper table was full tonight. We ate potatoes and some early radishes, and I listened to Joseph and Bronson dispute about the sensitivities of vegetables. Joseph maintains that they can feel pain and thus should not be boiled. Truly, he claimed that he can hear them cry out in their agony. Though I thought this to be utter nonsense, I held my tongue and listened more closely to the others’ words.

Here for just a day, I am already aware of my shortcomings: my leather shoes, made of the skin of some hapless cow, my silken kerchief woven out of a worm’s usurped labor. Even the honey in which I used to dip my morning bread was wrongly stolen from the mouths of bee-babes. And now—alas!—I realize the true origin of the taper by whose light I write: an unholy mixture of beeswax and tallow. I have come like a thief in the night and stolen away what is rightfully another’s—even if that other is an animal! And so, I blow out this wicked illumination and resolve to arise tomorrow as a new man, Adam, in a garden of righteousness.

June 9

Bronson and I set our backs to hard work today: breaking up the clods of earth so that we might plant our crops. Our work might have been made easier had not Joseph tried to wrest the mattocks from our hands! He came rushing forth from the barn shouting that we were defiling the earth with our foul instruments. I suppose he’d prefer us to dig only with our hands! Thankfully Bronson was able to calm him. Truly, it is hard enough to farm without a horse or oxen to pull the plow. It grieves me to think of how thoughtlessly I demanded the beasts to toil on my father’s farm.

June 11

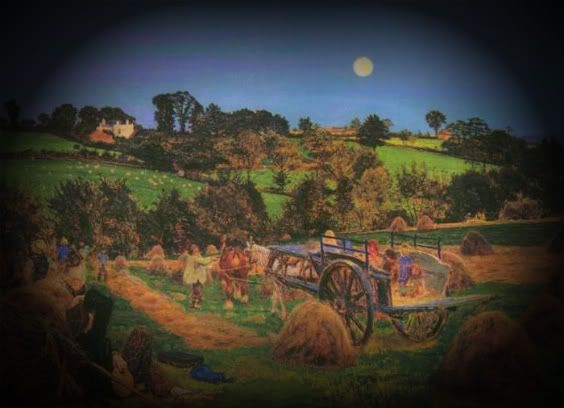

There are no candles to be had here, nor any whale oil lamps, so I will write by the honest light of the sun and sleep in the dark, not befouling the pure night with artificial illumination. Thus far, the days have brought great labor and great joy. At the morning and noon repast, Bronson and Charles filled my ears with their excellent philosophies. They talk at such a pace that I can scarcely get a word in. Today, they bantered about our diet and how it relates to our purpose. We drink only water, eat only grains and vegetables and fruit—and of that only what we can grow here. There is to be no commerce, no trade, no reliance upon the outside world. We are to be set apart, free of material desire, pure and sacred. Morning and afternoon have been spent alongside my brethren, turning the rich soil of the fields and readying them for planting. It is late in the season to be setting seed, so haste is necessary if our plans are to be realized. Farm work has never felt so pleasant to me, as setting new grafts on the apple trees, I was able to breathe in the simple, nourishing air of freedom.

June 13

More men have arrived—we are now a happy dozen, plus Abba and her children. All put their backs happily to the traces—quite literally, since we are without oxen or horses. The labor in the fields scarcely left me able to converse with the new men over supper, but I am sure the coming days will bring us closer. I am worked to the point of exhaustion and so to sleep.

June 14

Some of the new men are vexingly odd. While all of us have discarded our wool (stolen from sheep), silk, and cotton (slave labor being even worse than animal labor), in favor of linen and canvas, there is one fellow, Samuel, who wears nothing at all. Bronson says Samuel wishes to live in the original state of man. To this end, he also does not speak, for the first man had no need of language. Nor does he do any work, for the same reason. I wish this virtue of silence were kept by others of the community, for there is new fellow, Jonathan, who spouts nothing but rude nonsense and vitriol. Believing that no words are forbidden and that he should always speak his true mind, he curses in a most foul manner, and if I weren’t constrained by a belief in peace, this morning I would have lifted my shovel from the dirt and planted it instead on his filthy head. The man rants and wanders about as his soul inspires him, which means he is yet another doing nothing. In fact, I am one of the few who seems to complete any task. All others are poets who must find their muse or soft-handed sophists who are better suited to letters than to labor. At least the potatoes, corn, and barley are in the ground. It is probably better to let the poets avoid the farm work. When Charles and Isaac did attempt some sowing, I found them scattering a motley assortment of seeds into the same rows, as if barley and oats and corn could grow side by side. When I protested, they laughed and said that Nature would sort it out. If only my father could hear that!

June 16

Delightful supper! Bronson’s wife is a kind soul who is letting me share the light of her pine knot as I write in this journal while she mends a hole in my linen tunic—the garment of choice for Fruitlands’ menfolk. My brothers here, for all their sometimes lunacy, are learned men. Tonight, Charles read from tracts of eastern philosophy about the sacredness of the elements, the idea that air and water and earth as well as fire are all pure and holy. Bronson, hearing this, then advocated that we not sully the water with our bathing nor harness the fire to cook our food, and a lively conversation ensued between Isaac and Charles. They both know so much about other philosophies. Beside them I feel like a real country bumpkin, but it is pleasant to listen.

Though their knowledge of philosophy is impressive, their knowledge of farming is less perfect. While we were plowing the last fallow field near the creek, I asked Bronson if we might mix in some manure for fertilization. He scoffed at my suggestion and even seem offended; just as we mustn’t use leather, we mustn’t use manure, he said. This beggars belief. For while I can see how a cow needs its skin, I cannot fathom how it might use its own excrement. Hopefully Providence will deliver us another means of fertilizer.

June 23

As I worked this morning to dam up a river so that we might irrigate our Edenic fields, Bronson and Abraham (who has lately changed his name to Woods, where, indeed, he does spend most of his time) were hard at work uprooting the crop of potatoes I spent last week planting. They did away with the carrots and beets as well, and at lunch banned any further planting or consumption of such vegetables “as shove their unruly roots into the pure Earth.” Charles further extemporized that these plants show a lower, base nature by growing downwards and we should nourish ourselves only on such plants as grow up, towards the sun, as befits the natural order and only modestly disturb the ground and the air. I hope that we can survive on burdock and mustard, the only weeds that seem to grow in these fields. No doubt tomorrow someone will be ripping out the dam works I toiled over today: after all, I am corrupting and usurping the natural flow and freedom of the brook.

June 24

I came here to be free. To live simply and take only what I need, hurting no one else in the process. To reengage with the essence of life and contemplate the better parts of the world and Nature. One need look no farther than the view from the barn door—to see the splendor of this ideal. The sun rises, throwing its rays upon the tight, green orbs of the apple trees, the tender shoots bursting from the neatly mounded garden rows. The promise of freedom, the promise of plenty—if only we don’t want so much—is in these leaves, these fruits. This morning I sympathize with Samuel, the one who wanders about naked, and wish to bare myself to the world, become one with the Earth beneath my feet, unshod, unclothed, an essential man. I think of my father and my brothers shut up and imprisoned on their farm, by their debt, and wish that they would realize what a glorious life is possible for them.

Later, June 24

All, that is, within reason. Of which Bronson and Charles have none. I was chastised this afternoon for picking cankerworms off the young fruit of the apple trees. Imagine! “Brother Adam,” chided Bronson, “that worm has as much right to that fruit as you! Perhaps even more.” Brother Bronson, I longed to say, that worm has more sense than you. Moreover, if you let this worm stay, he and his brethren will eat every fruit, every leaf, and then may well turn to your flesh for sustenance, never minding the rights and freedoms of anyone. But I bit my tongue and let the cankerworm be.

June 25

At today’s Meridian Meal—as Charles calls it—Bronson raised the noble question: What is a Man? I answered that man is but a creature, which I thought to be a fine response, reflecting that we are part of Nature, not above it. But the others quickly discarded my reply as too simple. Isaac maintained that man is an animal with a mind. Woods claimed that we are but a body and Bronson, finally answering his own question, postulated that man is a soul and a mind, nothing more matters. Would that he were right! For beneath this noble discourse only a few humble plates of barley porridge and stringy greens were passed. If only we were mind and soul and could be nourished on such learned conversation. But my very mortal stomach rumbles its dissension from this position, and I find myself imagining the smells of my mother’s fruit pies, her molasses candy. To be pure is one thing. To be a man is another.

June 27

One of our members, Isaac, left today. He was caught drinking milk at the edge of the apple orchard. I can’t imagine where he obtained the illicit fare. Whether stolen or purchased, either is a crime against our community and our standards. Still, as I watched him walk down the lane, dressed once again in his woolen shirt and trousers, sturdy leather belt around his waist and good leather shoes upon his feet, I felt a stir of envy. That rather than being cast out of Paradise, as Charles and Bronson said he was, he was more a man brought back to life, a lost sheep returned to the fold. Truly, if somehow a bowl of milk were placed in front of me, I am not certain I could constrain myself. Of late, my stomach grumbles its discontent with the meager fare here. But I console myself that nature shall provide.

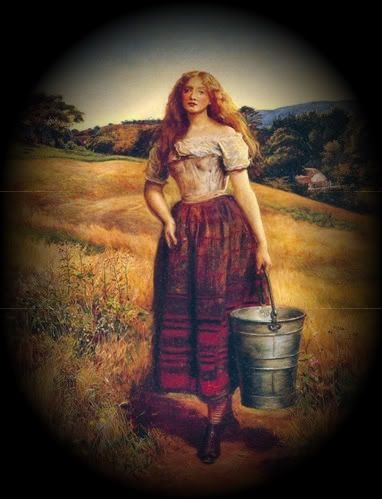

The sun is shining brightly on the fields, and I can see, from my perch against the trunk of an oak tree, Bronson’s children running down a slope behind the house. Their linen dresses and long hair stream out behind them and they stretch out their arms as they run—pell-mell—down the slope. They look as if at any second they might either fall or take flight. Which is more likely—for anyone here—I cannot say.

July 1

For these weeks, I must admit, life at Fruitlands has been little different than life on my father’s farm. I certainly thought there would be less labor in Eden! Now Bronson says we should go and split wood to store up against the winter weather. He spoke to the whole table at noontime, but truthfully it will only be he and I who go, for Charles is kept busy teaching the children and Samuel has said he needs no fire to warm him—though no doubt come December he’ll be closest to the stove and clothed again as well—and Henry (the newest member) complains of blisters on his hands, which are unused to handling anything heavier than a pen. So, the work once again falls upon my shoulders while other men follow their muses and their minds. Those at Fruitlands may disparage the use of animals as beasts of burden but have no trouble so employing me in identical manner.

July 6

I was sent this morning down the lane and across the river to the nearest neighbor to borrow from him a handful of nails—I say borrow, though truly they have been liberated, as Charles and Bronson will never repay except with the hot air of their philosophy. I wasn’t on the other farm but a few moments before the scales fell from my eyes, the veil behind which I’ve been living this past month was ripped away. The woman of the house who greeted me at the door could scarcely contain her surprise and amusement at my appearance—my linen tunic, my feet roughly wrapped in canvas—and felt so sorry for me, with my sunken cheeks and thin wrists (I caught sight of myself in a looking glass at the farm—there are no mirrors at Fruitlands, for Bronson wants no vanity, no false reflections), that she offered, in addition to the requested nails, a plate of bread thickly smeared with butter. I ate it. As I ate I gazed out on their orderly fields and orchard, the neat rows without any trace of worm or nudist, no wandering poets trampling the tender shoots, which would tower over the feeble sprouts at Fruitlands, denied as they are proper fertilization. Never have I tasted anything better than that bread and butter: scarcity has sharpened my tongue’s sense. With my final swallow I realized my guilt: this simple farmwife was my Eve, plying me with the forbidden fruit of a hidden serpent. Now that my eyes were open, could I go back to Eden? I took the nails and departed with a hasty word of thanks, returning to Fruitlands (whose fruits now seem bitter… destined never to ripen on my boughs). I made sure that all were at work or, more likely, at leisure, in the fields before leaving the handful of nails—with which they may crucify themselves—on the table and gathering my few possessions. I fled down the road and now wait, hopeful that a cart might come to help me on my way, consoling myself that Adam ate and realized, being newly endowed with knowledge. I too am wiser for my illicit repast, and now must go home and admit my errors. I can only hope to be received with half the welcome the prodigal son was granted. And if my father sacrifices a fatted calf in honor of return, I shall eat my portion gladly.

Alex Myers lives and teaches in Rhode Island. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in a variety of locations including Apple Valley Review, flashquake, and ghoti mag. Full details at alexmyerswriting.blogspot.com.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

My ideas, especially for historical pieces, come from what I read. For this piece, the topic occurred to me as I was reading Susan Cheever's American Bloomsbury.

0 comments:

Post a Comment