A Day for Burying

by Mary Akers

Emily pushes aside the curtain in the front hall and looks outside, checking the leaves of the rhododendron bush as she does every morning: open and flat. The air beyond the sill is warm then, warm this first day of April—above freezing, certainly, since the leaves have lost their curl, a more reliable measure to Emily than any thermometer.

In this modern era of change, in the year of 1903, with thinking so advanced and New York state crisscrossed by modern canals and home to progressive freethinkers, suffragists, Quakers and reformers, Emily feels a little backward still dressing according to the mood of the rhododendron leaves. But she is a woman of the land, if nothing else, something time and progress will never alter.

After dressing, Emily steps outside and scans the cottage grounds for evidence of mischief. On previous April Fools she has been caught off guard by the pranks parlayed between her husband, Scott, and his older brother Henry. Their first year in Boulder Cottage (can it be six years, already?) Emily and Scott awoke to find giant footprints outside the door. Footprints of what could have only been a great, man-like beast—a beast which they discerned to have been circling their snowbound cabin in the night. The tracks, they later learned (after a morning spent scratching their heads, with no small amount of foreboding), belonged to Henry, made whilst wearing a pair of hand-carved, oddly-shaped, giant wooden “feet” over his boots, contraptions of his own making, designed for the sole purpose of befuddling his younger brother.

And last April, late in the evening, when the day seemed to have passed without prank, odd animal sounds took Emily and Scott to a rear window, downstairs, behind the davenport. Just as they were staring hard into the moonless night, searching for animal movement against the snow-covered landscape, a face pressed itself to the pane, eyes opened wide, false teeth thrust out. Henry, again.

Emily remembers the pranks with a distant fondness as she stands on the front stoop of the cottage and takes in a deep breath of the early spring air—cool enough to tingle the lungs, with the spicy undertone of a balsam forest. It is delicious.

Upon returning to the cottage and closing the door, she records her thoughts in the dog-eared leather diary, gift from her recently deceased mother.

April 1, 1903.

I have thoroughly inspected the cabin, and the only jester this April Fools appears to be Mother Nature. The winter snows are melting. Melting, as if it were a sudden summer’s day! I have opened both the upper and lower windows—oh, that winter might be so easily carried away—and will set the sheets to boil. The rugs, also, are in want of shaking but they will wait a few weeks more. (Dust, I find, waits most patiently for me to notice and attend to it.)

Today the sun is startling and bright, the air clean and cool, but warm enough for the rhododendrons to have uncurled their broad leaves. The roof drips steadily beyond the eaves; low spots all around the cottage have formed puddles of opaque, wet slush. Perhaps we will soon be out and about without snowshoes. I sorely long for that day. Spring fever is upon me!

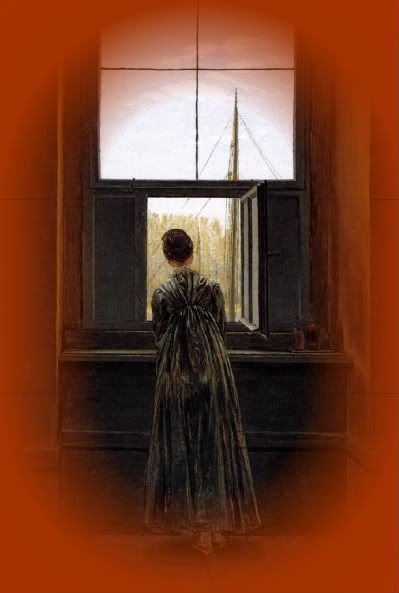

And upon Henry and Scott as well, it seems. I had forgotten that today was the day they planned to take the buggy into Keene Valley. When I heard the sound of horses in their traces, I ran to my upper window and watched them drive away. Their hats were set at a jaunty angle and as I watched them round the bend, I thought, Have there ever been two brothers more alike and yet more different? Or perhaps it is just my curse in life to be always thinking such thoughts, comparing and contrasting even those I love.

And of course, dear Scott I love completely, as a wife loves her husband. But beyond that love, I find (on those occasions when I search my heart), that I also love him as my brother and my father and my son. Ours is a relationship not only of passion, but also of camaraderie, protection and nurturance, so he can, by turns, be any one of these to me. And having written that, perhaps my further point will make more sense: I find—when I view them at a distance, in such a certain way—that I love Henry and Scott equally, as a mother might two sons. I love Henry the guide: his rugged, confident, gentlemanly nature; his quiet choice to live the rhythm of the seasons; his solitary sojourns into wilderness; his mischievous and impish heart. I love industrious Scott, my Renaissance husband: his scholarly endeavors and poetic musings; his attorney’s skill, applying the rule of law; his postmaster duties; his fatherly patience; his loving tendencies and pure, artistic heart.

And when I see them in their woolen knickers, long socks meeting the button cuffs, hiking boots donned, I love them both. And wonder, would others think me ill? Perhaps. And yet I feel it as a gift, this particular, open, kindredness that lets me know them as themselves and love them, deeply, both.

By the Ides of April, the only remaining snow lingers as a grey, granular presence, filling the crevices and shadowed spots where sun has not yet ferreted it out. The male house wren, returning early, an advance notice of spring, greets the day with his cheerful song, a pleasant descending gurgle repeated in the morning’s stillness. Emily has not yet seen the female house wren, but hopes—like the male—that she will soon arrive to begin re-feathering the nest.

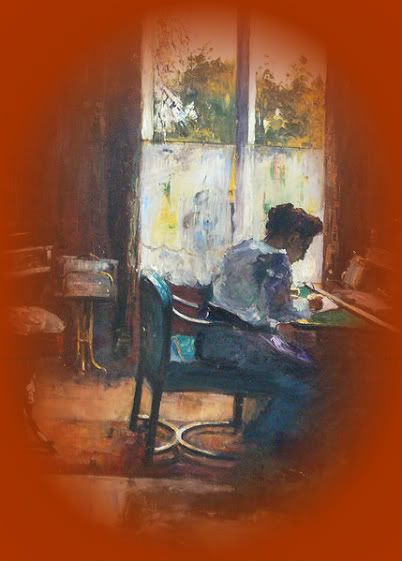

Emily pulls the chair out from her father’s old mahogany secretary, and sits. She arranges her skirts and prepares to write. April 13, 1903, she begins.

A shaft of sunlight streams across the page and the wren trills in the distance, singing from a tall hemlock at the edge of the forest. His warbles spring forth clear and loud then trail off to a soft vibrato as his lungs empty and his voicebox stills. Emily stares into the drawers that line the back of the secretary, opens and closes each one, straightens the blotter, then writes:

The forests rise with the scent of warming birch and balsam, they stir with the movement of winter’s denizens arising from sleep, and even Laundry Brook seems alive and ready to greet the challenge of this glorious day. Surely it would be a sin to do less than bask in this day the Lord hath given us, and so bask I shall, and let the chores of Boulder Cottage sit and simmer for another day. Outside is where I must be!

Henry is the first of a group of guides and wives to arrive for a May Day supper-gathering. Henry lost his wife in 1870, in their first year of marriage, to childbirth; he has not remarried, turning his life to the woods and lakes, instead. Emily suspends her struggles with the butter mold when Henry arrives, crosses the floor and kisses her brother-in-law lightly on the cheek.

“Good evening, Henry dear,” she says, rising lightly on her tiptoes for the kiss. Henry colors and touches the spot with the rough tips of his first two fingers.

“Emily,” he says in reply. He doffs his hat and holds it by the brim.

Emily is certain that tonight’s dinner discussion will center on the lack of rain—more than a fortnight they have been without. The Upper and Lower lakes are both down and the river is but a trickle compared to the usual rush and tumble of springtime. But she does not speak of this with Henry. Lately his presence seems to render her embarrassingly mute, despite their years of close association.

“You are well, then?” she manages to ask, and turns to find Henry suddenly, alarmingly, beside her.

He nods and smiles. “I am,” he says, and she notes, again, the shining fleck of gold in the corner of his otherwise brown iris, the crooked tooth that sticks forward at the front of his grin, the charming freckles that, even at age fifty-two, still span the bridge of his nose, so like her own son’s, when he was young.

Before she can think what else to say, Scott comes to the front door, leading the next round of guests, all bluster and goodwill, hugging Henry heartily and slapping his back.

After the last guests have arrived, the dinner been consumed, and the topic of rain exhausted, the men take turns entertaining the assemblage with a round of amusing backwoods tales, as only guides can do.

Henry stands, the first to tell his tale, all shyness gone in the amber glow of candlelight and rapt, attentive listeners.

“There was a bear,” he begins. “A bear I’d tracked for three long days. Three-hundred-pounder, at least.” He opens his arms to their full span for emphasis. “Black bear.” He curls his fingers like claws and menaces a nearby diner. “And that bear knew I was following him, too. Looked back at me, he did, more than once, as if to ask, why, in an offhand manner, should I be trailing him?” Henry opens his eyes in mock innocence and scans the faces of his seated listeners.

“Then!” he shouts, a little too loudly, and the nearest guide’s wife jumps. Henry allows the ensuing silence to stretch, and leans forward, lowering his voice. “The bear turned around, put his nose to the ground, snuffled, and that old fellow began tracking me!”

Henry tiptoes around behind Emily and grabs hold of her chair’s back posts. To her delight, he jiggles the chair and growls before continuing.

“Well, I turned, then, quick-like, you can bet, and started walking back the way I had come. I heard him behind me—snapping branches and breathing heavy. I knew there’d be no chance outrunning that bear, and I knew I had to think fast. It was then I had the idea to distract him.” The diners around the table have all gone still, even the guides, who have surely heard this story before. Emily’s eyes are wide and white, glassy in the flickering light.

“How does one distract a bear, you ask? Well, I’ll tell you. I opened my canteen, set it on the ground and moved back a step. And what do you think that bear did?”

Several heads shake ever so slightly but the room is silent. With that as his response, Henry continues. “That bear came forward, right up to me, and he looked me over. He stood so close I felt his breath against my breeches; he lifted his muzzle and looked me in the eye, then gave a hot snort—right by my cheek—it smelt like salty ham. I didn’t move.”

Henry stands very still, arms held stiffly by his sides. “Then that bear turned from me and sniffed the canteen. He grabbed it in his great paws and lifted it up to his mouth. He drank it dry, he did, just like a man. Then set it back down, grunted in my direction—as if to say, Thanks!—and walked away.”

Emily and her guests clap their hands and laugh as Henry moves into the kitchen, lumbering in an awkward, bearish gait.

* * *

May 15, 1903.

Today has been warm and lovely, again. Scott’s entry for the Superintendent’s log read, 73 degrees and sunny, and this same day last year he recorded a mere 42. The skies have shone clear, a lovely light blue—the very color of a robin’s egg. A slight, warm wind blew all day from the southwest. And yet, despite this cheery warmth, the forests in the Reserve are sorely in need of rain, dangerously in need, as Scott, by telegram, has informed the stockholders. This morning we made a brief hike to Lower Ausable Lake; each step crackled underfoot as if the season were a dying fall and not arriving spring. Scott, a generally cautious man, not prone to ominous predictions, in his logbook wrote, “Woods a giant tinder box.” Each morning he scans the skies for signs of rain.

Still the season is opening well, despite the dryness, or perhaps because of it. For recreation, at least, the rainless days have been a blessing. Many a family has booked a stay this spring, many are already here. This year accommodations at the Inn have been set at $2/day. Scott and all the AMR stockholders are predicting a solid solvency for St. Hubert’s Inn this season. This is my fondest wish as well. I should think thirteen seasons of struggle would be quite enough.

May 20, 1903.

Having read again my most recent entry, it occurs to me that I have never described the AMR. Certainly I hold no high notions of my humble words, nor do I imagine a reader other than myself…and yet, should I not offer explanation as if this were, in fact, a great epistle I am writing? Should I not hold true to standards of literary etiquette and explain myself?

Seven men joined together to purchase thousands of acres in 1887, with an eye to profit from the sale of timber and lakefront lots. They named it the Adirondack Mountain-Reserve and incorporated it as a business venture. For the guides, who felt their own sense of claim to these wild mountains, the AMR became first a trial (hunting was banned, fishing restricted) and later a safety net that maintained their mountain livelihood. For others, like Scott, a higher purpose held: one of preserving a large tract of unspoiled, wild land such as one rarely finds in these modern times of change and bustle. For myself, I have been happy to know that the plants and animals will always have a home, a place to live and grow as nature intended.

And of St. Hubert’s Inn? Construction began in 1890; a naming contest was held and St. Hubert (a 7th century hunter who spent his life protecting wild animals after his conversion) won the use of his name by a vast consensus. We not-so-saintly humans have done our best to carry on his legacy.

May 25, 1903

This evening, early, a great electrical storm approached with alarming speed and threw itself, mercilessly, upon us. I am sad to report that lightning struck an area beyond Mt. Dix. Within minutes of the strike, as if fulfilling Scott’s predictions, a plume of smoke rose into the air. As we watched, it grew into a great tornado of fire, a roaring, locomotive mass that could be heard for miles. No human power could have contained it. Even as we watched, the flames climbed to the summit of Dix and swept over neighboring Noonmark Mountain. And all the while, the storm clouds stubbornly held onto their rain. The woods are seven long weeks without moisture. Scott has spent the evening telegraphing—exploring all available resources and able-bodied men for immediate dispatch.

May 26, 1903.

Last night was not a restful sleep. In fitful dreams, I watched yellow bolts of lightning strike over and over, igniting and inflaming my beloved mountains. I stood, in the dream, mute and helpless, frighteningly close to one sharp bolt that landed in the upper story of a massive hemlock. A few feet away, a wide-bodied raccoon, grey in the face—just arising for his evening forage run—joined me in witnessing the strike. Paralyzed by the deafening pop and fizz, he stood motionless, front paw lifted in surprise, while a bright orange flame traveled down the trunk. The raccoon’s ears pricked at the sound of spreading fire; his nostrils flared in response to the acrid smell of searing wood. Two blackened limbs hung precariously above him, smoldering. When the fire had taken hold and the heat could surely be felt even through his wiry pelt, the raccoon turned and lumbered away, fire spreading behind him.

May 27, 1903.

Fire reached the Reserve today, as Scott had suspected it might. Alas, such foreknowledge does not make the reality any easier to endure. Every man in Keene has been ordered out to fight and, if possible, to prevent the fire from spreading and crawling down this side of Noonmark and Round Top. If it does, we will surely lose St. Hubert’s Inn and all our cottages. I can hardly bear to think of it.

Reinforcements arrive, singly and in groups: Elizabethtown gentlemen, businessmen from Keene, rugged guides, reporting from the farthest outposts. They arrive, laden with pickaxes, hoes, canteens, handkerchiefs, stubborn resolve and righteous indignation.

These men chase the fires, scaling mountains, walking miles, exhausting themselves in advance of the fight, and my own dear Henry is among them. I pray for his safe return even as I imagine him working to exhaustion, stumbling onward, lifting his handkerchief to drink, mouth blackened with soot, breathing through smoke-ringed nostrils.

May 28, 1903.

We women have become soldiers in this war. The wives of a number of our guides have walked themselves to the Inn without—as more than one has said—precisely knowing why. But they are here, seven of them, and we are battle-ready. Our aprons are our armor, and St. Hubert’s Inn our battleground. We roll up our sleeves and set to work making dozens of leavened and unleavened loaves, in shifts, all hours of the day and night. Biscuits and boiled potatoes. Viands and rabbit stews. Coffee, thick with sugar, to fortify the men. Our wrists and backs ache, our hands are raw from chopping and from washing; our feet swell. And still we stay and work and fight, for what else can we do? There is at least some comfort in the flurry and bustle of many women set to task.

And when propriety no longer serves to contain our speculation, as so often seems to happen in a group of women working, we flip the dough onto floured boards and discuss the rumors all have heard—rumors of fires being deliberately set so that a man might earn $2/day in firefighter’s wages. We knead the dough, round and tuck the rolls, and look amongst the faces of the men at table, all the while wondering if this or that good fellow could have been the one to start the very fires of Hell.

May 29, 1903.

The Openheim’s have lost their home. And Charlotte now works among us, come to do what she may to help, her home no more in need, her former life extinguished. Charlotte does not cry, but also does not talk, turning, instead, to work for solace. From the hard curve of her back I feel her helpless anger, and I, in turn, am powerless to touch that wounded place in her. I, who have not lost my home, cannot know her pain, and as her posture tells me, should not try.

And yet I have felt a pain, a loss, perhaps as deep as hers. Although my cottage stands, I have nonetheless lost much that I hold dear. I have walked into the charred remains of my once halcyon, sylvan, sanctuary. I have crunched the embers of lost life beneath my bootsoles, wandered through a sad grove of armless blackened poles. I have seen a bird that was not a phoenix flying through the air. Flying and burning.

And in the midst of all this chaos, unaffected by the drouth and fire and human suffering, the rhododendrons on the grounds are cheerily swelling their buds, rosy red and ripe to bursting. By tomorrow they will be a riotous confusion of pink fecundity, all beseeching petals and powdery pistils. Though there will be no bees to mate them one to another, still nature strives and tries.

May 30, 1903.

250 men are fighting fires from Nippletop to Round Pond, in Chapel Gorge, on Round Mountain, and Noonmark. They trench and dig, stopping only to drag themselves to the Inn for replenishment, their very aspects dripping with fatigue.

Late yesterday there came a further discouragement to us all. Despite the men’s best efforts, the fire reached 400 cords of pulpwood, stacked between Dix and Noonmark. A flame-colored pillar of smoke rose high into the sky, a pure, consuming fire, and Scott said simply, “The lumber is gone.”

As I watched, Scott by my side, I thought of all the hours lost in human toil, to fell and cart and bring it to a stack where it would serve only to feed this giant fire. Scott, I am certain, saw the income lost, as if money, in a pile, were burning. And I wondered where Henry was when he (surely) noted the loss, and where his thoughts had carried him.

Scott and I move through our days like the stunned and wounded men returning from The War Between the States. And yet, last night we found some solace in our conjugal bed. Despite fatigue—the likes of which has superseded even last year’s exhausting deathbed watch of mother’s suffering—we talked for hours, side-by-side in bed. At times, our words were punctuated by sobs, and yet the tears seemed to wash us clean. And when we were done we reached for one another with a mutual, unspoken need. Like the rhododendrons, we stubbornly reclaimed our aliveness, our refusal to surrender to that which would erase us. And though my womb is far too old to seed, still our bodies strive, and find, like nature, comfort in the action.

May 31, 1903.

As I sit and write by my cold and empty fireplace, I wonder at the many hours I have spent in the thrall of fire. Out in the woods at camp, or by my own cozy hearth in Boulder Cottage, I have delighted in the warmth against my skin, the tightening glow, the dance and flicker of flames, the snap and sizzle of burning sap that drips like liquid fire.

So how am I to reconcile that joy with this fire that rages beyond my door? This all-consuming beast that roars in the distance, self-fed and ever hungry? This fire that destroys my beloved mountains whilst I am powerless to stop it? How can it be so calming when harnessed, so destructive when untamed? The cozy hearth cat and the wild catamount. Tonight I feel within my breast a similar pit of wildness and I am unable to will it down.

June 2, 1903.

Henry has not returned this night. The group with whom he left has seen no sign. My hand shakes, even as I write these words. Scott professes confidence but there is worry behind his eyes. For myself I can scarcely bear the thought of Henry come to harm, and so I push it from my mind and pray for mercies. Still I find myself searching the scant remaining woodline, starting wildly at each opened door, staring down any fellow who emerges, nursing a violent dislike—no matter the man—so long as proves to not be Henry.

A large force of men have begun trenching within the grounds of the Inn. I see them, hunched forms digging to task, and wonder why none are out in search of Henry. Perhaps with no wife nor child at home, the would-be searchers feel no need. But I do. I have walked amid the devastation calling out his name, venturing as far as I dared.

June 4, 1903.

I write the fourth, but I do not know if today is the fourth of June, or if it is the fifth. Time has become a measureless entity. Or perhaps an entity measured in meaningless ways: the length and breadth of trenching efforts, the acreage destroyed, the mountains overcome, the buildings lost. Such natural measurements as night and day are moot. Fires light the skies so that night is not night. Ash greys and clouds the sun till day is not day. Soot and smoke are everywhere. The air, the water, the food, all that we consume tastes of it. Meals are whenever time allows or bellies cannot be forestalled a moment longer. Breakfast is the name for every meal, every meal the first meal of a measureless day.

The telegraph wires are down. Scott attempted a post earlier this day, and received a chilling silence in return.

June 6, 1903.

Today has been a day for burying, and I am tired. Down by Laundry Brook, I have been, consigning my jewelry to the earth, my children’s teeth, my mother’s brush and comb, my favorite paring knife. Burying, in order to save. For a moment I interred this diary as well yet found myself unable to cover the book with dirt, the comfort of writing down my thoughts too great a comfort to forego.

I do not care to ever see a shovel again. My boots, dust-colored and dry, are caked with sooty flakes, my palms blistered, my instep sore. My hair no longer has a color. Except, ash. Ash, the color of my hair. I brush it out at night but soot is soft and so it spreads the length. And powder only makes a thicker, lighter grey. There is no time to bathe. No inclination other than to save: the woods, our homes, the men we love, every drop of water for the fire.

June 7, 1903.

The unsettling dreams continue. In one, I stepped outside, body rising high above the clouds of soot. Wind whipped at my nightclothes and tossed my hair. A bank of lighter clouds approached and darkened. The air became thick and still. Particles of water formed around me, moisture covered my skin and gathered into droplets. Rivulets of rain traveled down my arms, dripping off my fingertips as their own weight pulled at them. One fat drop landed on a hot rock and turned to a sizzling spatter. Another hit the earth, erupting upward in a circle of dust. Below me, a doe and her fawn, exhausted and confused, slumped in the dampening dust and sighed. Henry appeared; he took a seat beside the doe and stroked her gently, along the flanks, like a lover.

June 8, 1903.

Today the dream is realized! I felt a change in the breeze moments before the rain arrived; the hair on my forearms stood in anticipation. Then my reckless feet carried me out the door and into the yard. The moisture, the wetness, the droplets, the rain! It felt glorious against my skin, so parched and long dry. I raised my palms heavenward and the rains answered in great torrents. A drenching downpour soaked my hair and skin, ran down my open throat, and made my clothes cling wetly to my body.

Oh, I am not so old that I may not enjoy the pleasure of a body, wetted and cooled after so long a dryness. I hope to never be so old as that! And as rain washed the years away, I found myself stomping and splashing in the puddles, kicking at the water joyously. Oh, what would Scott have thought if he had seen me? But in my state, I would have given him no time to think, but grabbed his elbow and engaged him in an impromptu Virginia Puddle Reel.

June 9, 1903.

The glorious, revivifying rain has been falling for 18 hours. It is a great soaking rain that has set the balance right again. Amongst those weary stragglers (us!) who have remained behind, there has been much rejoicing and camaraderie, for not only is the fire out, but Henry has returned! Bedraggled and ravenous, with horrifying tales of narrow escapes and one of a beautiful doe leading him to safety. His arm rests in a makeshift sling yet he shrugs off all concern. But Henry is here at last and he is safe. Words cannot express the joy I felt at meeting his searching, desperate eyes, as if he, too, had been worried for me.

Even as it begins to fade behind us, this disaster remains too large to comprehend. And yet we continue on, for what else can we do but—like the rhododendrons—keep moving forward? We have only what we have before us. And the best we can do, with these days that we are given, is to take our cue from nature, and keep going. We do what we are able. We strive and try.

* * *

Author’s Note: The Adirondack Mountain Reserve, the first privately owned nature preserve in the United States, encompassed approximately 25,000 acres of New York State high peaks wilderness at its incorporation in 1887. The AMR was managed by seven wealthy businessmen landowners who acted as trustees. In 1903 a tragic forest fire spread through much of the Reserve, destroying old-growth forests and threatening St. Hubert’s Inn, the private guesthouse of AMR members. Although its boundaries and acreage have changed over the years, the AMR remains in private hands and the original Inn still stands.

Mary Akers' short story collection WOMEN UP ON BLOCKS won the 2010 IPPY gold medal award for short fiction. She received the 2008 Southern Writer's Award from TBRA Publishing and produced a book of short performance pieces for dramatic high school performance with same. She also co-authored a non-fiction book titled ONE LIFE TO GIVE that has been published in seven countries.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

Most of my historical fiction is inspired by visiting a modern location and learning about its history. The facts I pick up are generally dry ones--names, dates, statistics--but they often lead me to imagine a living, breathing person in that space during a very different time. In the case of A Day for Burying, my husband and I have backpacked in the Adirondack Mountains every summer for ten years, including many of the mountains referenced in this story. Writing A Day for Burying became a way to learn more about the mountains that I love and helped me to imagine the people who also loved them--enough to save them--so many years ago.

1 comments:

What wonderful artwork you selected! It fits the piece perfectly. Thanks so much, Megan. You run a lovely journal. :)

Post a Comment