The Silk Moth

by Jessica Owen

You have come to hear the story of the Silk Moth. This is the story as it has whispered from daughter to daughter in my house, for now legend has made her something she was not. Truth is the fish swirling below the still surface of the water, and you must look deep to see.

She was the finest weaver in the empire, and so in the world, but that is not why we sing her song. Before she was the Silk Moth, or a weaver, or anything more than what you are, her name was Li Shui.

“The master weaver is coming today.” The whisper traveled through Second house like the excited fluttering of moth wings in candlelight.

Mee stood over her row of iridescent chrysalises, moving the trays with the same careful attention as a duck shifting her eggs, into the warmth of ten red-flamed heat lamps. Each cocoon was the size and shape of Mee’s thumbs and beautiful, like the moon, like promises, like the flash of color within the shell of the oldest shellfish in the sea. Today these would give up their precious silk strands that could be woven together into threads, woven into cloth that could make women sigh and men do war.

Li Shui stood beside her, humming at her work with the toneless, sweet voice of a dove. Both girls worked in steady quiet, both pale and dark-eyed, slender from labor. They stood in the Second house, the outer work house, backs bent over the precious trays of cocoons. A dozen other girls ranged along one hundred such other trays, each tray with one hundred cocoons. The outer holding house was the largest besides the First house, where the little royal worms were kept and fed before they began spinning their cocoons. Mee and Li Shui’s work there had been so fine they had been moved to Second house to tend the cocoons, and Mee was grateful as she watched snow fall on the ponds outside of their enclosure.

Soldiers stood outside along the paths and beyond the ponds, young men guarding the silk houses against threats and secret-stealers. Now and then Mee would lift her gaze to search among the falling snow for one young man in particular, but from here they all looked the same in their red and silver armor, the armor that marked them as the guardians of the most precious secret in the world.

“Little spinners,” Li Shui was murmuring to her silent charges. Mee glanced at her sidelong, and her cocoons, which seemed to shift and shimmer under the light, under her dove voice. “Little master spinners, today the master weaver will see your strands, the most beautiful strands in the world. You should be proud.”

She was smiling and Mee caught her eye with a grin before looking back to her own tray. Her cocoons didn’t shift and shimmer, but the red-flamed lamps were dimmer where she stood.

“We should only hope to weave as finely as these,” Li Shui murmured to Mee, moving her hand over the cocoons but never, never touching them. Mee nodded, mute, seeing love in Li Shui’s gaze, and respect as one would give a master craftsman.

As Li Shui foretold, soon along down the rows strode the master weaver, her back straight as bamboo and her black hair shaved so that it never interfered with her work nor competed for the beauty of the silk threads. Li Shui lowered her gaze to her cocoons so she wouldn’t look anxious, her lips pressed tightly to keep from smiling. Mee did the same, though she had to swipe loose hair back behind her ear. They knew theirs were the best, the only ones ready and worthy.

At last the weaver stopped at their trays, her presence like the warmth and sternness of a furnace at their backs. Li Shui and Mee turned and bowed low, both hands pressed to their breasts, not speaking until spoken to. The master weaver was examining their cocoons.

“Bring these,” she said, her voice low and light and pleased. “Bring them to the Third house.”

The girls murmured assent and straightened solemnly, dark eyes bright as birds’ again. Once the weaver strode back out of sight they laughed, tears in their eyes, and hugged each other to stifle it. Too much noise would disturb the cocoons.

“Come,” Li Shui sang to her adopted brood of cocoons as she picked up the tray. “Come with me and weave with me, we will make cloth to make kings weep…”

Mee hummed along, not knowing the words because Li Shui made them up right then, picked up her tray and followed.

The Third house was indoors. They carried their trays through Second house for all to see and through the threshold of the Third house, pausing just inside to slip off their shoes. They stepped forward to bow to the little stone house god on his alter, who was sending up thick, curling incense. Inside, the heat rushed their skin and flushed their faces. Here the warmth was suited to the comfort of people, not silk worms and cocoons. Mee never felt this warm except when she slept.

Mee whispered to Li Shui. “If these give up good strands, do you think they’ll teach us weaving?”

Li Shui held her tray in front of the house god for a moment, letting the incense curl over the cocoons in blessing, before she smiled to Mee, sure as a rising star.

“They will.”

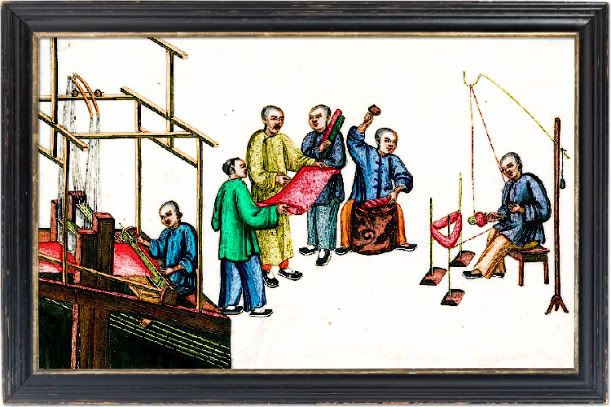

The master weaver came around the altar and smiled to the girls, motioning them to follow. The house was laid out in small rooms, warm, springy bamboo planks on the floors and veiled, translucent walls of undyed silk cloth through which they could see Fourth house – the weavers, the shadows of weavers, creating the wealth of the empire. Mee could see Li Shui straining to see behind these veiled walls, yearning to put her hands on the threads and create what those women were creating.

They came to stairs and Mee paid attention again. It was cooler as they stepped down and an odd smell drifted up, dank and too sweet, like water settled too long in wood, like mold or an old bird’s nest. Mee held her breath and frowned, glancing at Li Shui, whose sure smile had faded to pursed, tight lips.

At the foot of the stairs the way opened out into a vast room, a room that must have spanned below the entire Fourth house. Women worked here too, but not weavers and not singers who could care for worms and cocoons. These women looked hard, thin and strong. There was no singing here, and it smelled even worse of old water and something too sweet.

The dozens of women stood over massive vats of boiling water, vats they must climb ladders to see into, and also smaller basins of boiling water. In the corner Mee could see another group unraveling wet, sticky strands of pearly thread.

“This is Third house,” said the master weaver, her hands folded, hidden within her sleeves.

“But they’re killing them,” whispered Li Shui, her voice weaker than Mee had ever heard it. Mee hadn’t realized it, but Li Shui spoke the truth. They watched as trays of cocoons were lowered into the enormous vats of boiling water; the cocoons that they had so carefully warmed and sang to, the cocoons that held the worms they had fed the most tender mulberry leaves, the worms that were each one more precious than all the jewels of the empress’s crown.

“Be still,” said the master weaver. “They each render their strand this way. If we let them grow and break free the strand will be broken and lost. Be still.”

“No!”

Li Shui’s scream filled and then silenced the underground chamber. Every stern, leathern face looked at them until the master weaver barked them back to work. She gripped Li Shui’s wrist to drag her to the nearest vat. Mee followed meekly, unsure what to do. She loved Li Shui, but if this was the way of it, what were they to do?

Li Shui shrieked in anger and grief and wrenched from the master weaver’s grip, sending her precious tray up on end and the cocoons scattering across the floor. The master weaver threw her to the floor and six of the hard, strong women rushed forward to collect the cocoons. Mee cried out and put down her tray, hurrying to Li Shui’s side.

She wouldn’t stand up. She wept, reaching and clutching for the nearest cocoons to hold them to her breast.

“Little spinners,” she piped, stroking them with slender, trembling fingers. “Forgive me. Forgive me.”

“Li Shui,” Mee whispered, harsh, trying to tug the cocoons from her desperate grasp. “Stop this! Stop or we’ll never be weavers, they’ll never let you spin or sing again!”

But Li Shui clung to her little charges until the master weaver tugged Mee away from her, and in a frighteningly quiet voice ordered her back to her task. Mee turned away quickly to collect her tray and take it to the vat. Her heart ached a little, to be sure, but not like Li Shui’s. How could they suffer heartbreak over the thing that gave them their clothes, their wealth, the honor of their entire empire in the eyes of the world? She surrendered her cocoons to the boiler women and left in a hurry, head bent low so that she wouldn’t see the master weaver dragging Li Shui toward punishment.

Mee didn’t see her again until nightfall. The snow never stopped but swirled and filled the ponds until they froze over, blanketed the roofs, bridges and paths. Mee was glad she wasn’t on midnight duty; those girls who tended fires to keep the mulberry trees warm, and the worms and cocoons warm. She huddled in her bed, listening to the dozen other girls shifting in their beds, restless in the silence of snow.

A shuffle at the door remarked Li Shui’s return. Mee couldn’t see her clearly but only how she moved, stiff and slow. Beaten. She climbed into bed beside Mee without a word. Mee was quiet for a moment until she could stand it no longer, and found her friend’s cold hand under the blanket.

“What will happen?”

“They’re sending me back to First house,” Li Shui said without pause. Her dove-voice was hushed in the dark, somber and without argument.

“But that’s good,” Mee offered. “They could’ve put you to scrubbing floors, or waiting in the kitchen or warming the mulberry roots.”

“Yes,” said Li Shui without cheer. “They could have done all those things.”

“Tell me what happened,” Mee said, unable to stand the gray in Li Shui’s voice, usually so rich and warm with color. A sigh. Girls grumbled at them to be quiet. Li Shui shifted and Mee felt warm breath on her face as they faced each other to speak softer.

“The master weaver beat me, for spilling the tray. Then she instructed me. Oh, Mee, I know they’re only little worms as she says, but they’re everything to us! The silk threads are precious, but are the spinners that make the threads not all the more so? After they unravel the wet threads some of the worms are eaten, or thrown into the fire if they’re too small, or given to the empress’s great green herons or the emperor’s golden fish as if they were nothing but fly maggots.”

Mee rubbed Li Shui’s hand, trying to warm it as she spoke her grief. She could think of nothing helpful to say. “This must be as it has always been,” she finally murmured. “Because we know it now doesn’t make it any worse than it has always been.”

“She wouldn’t listen to me. She wouldn’t listen,” Li Shui said. “I said we should honor the worms for their sacrifice as we honor warriors, that they are serving the emperor and the gods as surely as we are.”

“You can’t change everything on your own,” Mee said gently, hoping to lighten her heart.

“I’ll make them see,” she insisted.

“Let it go.” Mee squeezed her hand. “You won’t think of it in time.”

Li Shui tugged her hand free at that and turned her back to Mee. After a silence so long Mee thought she had fallen asleep, Li Shui spoke, abruptly changing the subject.

“Do you hear from Huo?”

Mee’s cheeks warmed and she burrowed under her sheet for a moment. “He sends me notes.” She thought of her soldier, who was probably asleep in his own bed now after standing out in the falling snow.

“Promise me something, Mee.” Li Shui’s voice was a whisper now.

“Anything.”

“Promise you’ll marry him when he asks you, and be happy. I don’t think I’ll find a husband of my own.”

Mee laughed and girls hushed her from across the room. “But you will. A man worthy of you hasn’t come yet.” She laughed again, for Li Shui was more beautiful, graceful, and wiser than Mee would ever be. The low gray tone remained in Li Shui’s voice even though the request was sweet, the mournful tone of a dove. Mee tried to reassure her. “They say we’re like butterflies, too, that once we break from the cocoon of girlhood our womanhood shimmers like wings, beautiful wings that attract men in ways we don’t know. Li Shui?”

Li Shui didn’t answer immediately, but only when the room was so quiet they could hear snowflakes hitting the window. “Wings,” she whispered, and nothing more.

Mee did her work well, even if she was lonely without Li Shui, and as winter warmed into misty spring the master weaver at last brought her to the Fourth house, to teach her weaving. First came taking each steel-strong, nearly invisible strand the worms had spun, and swirling them together to make even stronger, thicker threads. Mee found this work tiresome and longed to work at the looms, turning long threads into cloth. The master weaver seemed to sense this, and for her impatience, made her work at spinning threads until summer.

The girls of First and Second house told Mee that Li Shui toiled quietly, sang as ever to her worms and then to her cocoons as she had before, but now her song was low and mournful, thanking them for their work but warning what was to come. They still shimmered in the light for her, Mee heard from the other girls, as if they didn’t mind their task, as if to reassure her. Mee missed Li Shui’s presence at her side so much that at times her chest ached and she had to put the other girl from her mind. At night they didn’t speak anymore, both so weary they fell right to sleep.

When at last Mee became patient and meditative and joyful in her spinning, the master weaver set her to learning the looms. For the first hours as she learned, she longed for the simple pleasure of twirling together the worm-strands. It was tricky, intricate work on the looms and the shuffle and crack of the other, skilled weavers unnerved and irritated her. Hands aching, eyes aching, she rose at last from her first day as evening sun glanced through the open doorway.

A shriek of pain and a harsh, chastising shout echoed from the courtyard.

“It’s Li Shui!” One of the other weavers cried from the door, pointing. The other weavers rushed forward and Mee was lost in their midst until she pushed her way through the older women to get outside. The stone and flower courtyard was painted pink and red by the dying sun and in that light Mee saw Li Shui on the ground, curled around herself, and a man standing over her.

“Huo!” Mee shouted, shocked and pained. She shoved aside the women nearest her and rushed out into the courtyard to grab Huo’s upraised arm, to stop the blow. “What is this?”

“Mee, step away.” He was a soldier, taller and so much stronger, despite Mee’s laborious tasks, and he pushed her off easily. “She is a thief.”

“A thief, no…” Mee looked from him to Li Shui, who remained curled and weeping on the stones. Her hands were cupped around something. Mee knelt beside her and wrapped a firm arm around her shoulders to help her sit up. “Li Shui, what have you done?”

The weaver women still crowded at the doorway, watching in captivated silence. Huo stood over Mee and Li Shui, shifting weight from foot to foot as he struggled with being the authority present and his love for Mee, and through her, Li Shui.

“Wings,” Li Shui said, and opened her hands. Mee sucked a breath through her teeth when she saw what her friend held.

“Li Shui, you’re going mad! You must be ill, let me take you to the physician.”

A pearly gray moth crawled in a delicate path around Li Shui’s fingers, fluttering dusty wings. Such a creature meant she had kept a worm in secret, kept a cocoon, kept a precious cocoon and let it hatch, ruining the priceless silk thread. Mee wondered when her friend had grown so far away from her that she kept such secrets.

“It’s only one,” Li Shui said, and cooed to the little moth, which quivered its antennae in return. “Only one. But you may beat me, Huo,” she whispered, looking up to his young face, full of sternness and heartache.

“You know that I have to,” he said softly. Mee hugged Li Shui’s shoulders tighter as warm tears slipped down her face.

“But first let this one go,” Li Shui said, her dark, mournful eyes bright with triumph. Huo was silent, his lips tight, and Mee couldn’t fathom the graveness in his eyes. Yes, a beating was terrible and Li Shui might go back to First House all over again, but a small part of Mee was happy for her, for this little victory. Li Shui raised her pale hand to the last rays of sunset and flicked her fingers gently, bidding the silk moth to go. It clung and quivered on her fingers before it fell, spinning and fluttering, to the stone.

“Oh,” Li Shui said, with a laugh like a mother, and put her hand down on the stones. The moth crawled up onto her fingers again. “Try again,” she crooned. “Try again.”

“Li Shui,” Huo said finally, and his voice broke. “Don’t you know? The silk moths can’t fly.”

Li Shui went still and raised her troubled gaze to Huo’s face. Mee’s throat clutched and she hugged her other arm around Li Shui’s shoulders, eyes stinging with tears for her.

“Go along now, Mee,” said Huo, the steel of the guard back in his voice. “Go along, and take the other weavers to supper with you.”

Mee glared at him, then she kissed Li Shui’s pale cheek. When Li Shui didn’t respond, Mee stood, and hurried to gather up the staring women from the Fourth house and herd them away. Li Shui’s cry of pain followed them through every wall. Huo told Mee later that he released the moth in a wild mulberry grove and she kissed him for it, but it didn’t ease her tight heart.

After that there was no more disobedience from Li Shui. After that, in fact, she drifted into becoming the most skilled and graceful of all the women in the silk Houses, and it wasn’t even winter again by the time she sat at a loom next to Mee.

Now and then, she even saw traces of peace and mirth on Li Shui’s face, which brought no end of joy to her own heart, and they talked as friends as the weather grew colder.

“I’ve heard,” said Li Shui as her hands danced across the loom, “That men have come from the west on fierce black horses, and dined with the emperor.”

“Yes, it’s true,” said Mee, and nodded to the other women who looked in their direction to listen. She tried not to be envious of Li Shui’s skill, who had been in the Fourth house for fewer months and was already the best of them all. “Huo told me. He said that the men are large, dark and rough, but they speak freely of the world to the west, and they think they know the secrets of our thread. Huo said that tomorrow they’ll be shown the mulberry groves and the weaving rooms. We are to weave more tales for them and let them think they’ve guessed right.”

All the women gasped and laughed and began thinking up ways to guard their secrets. Li Shui came up with the first, dark gaze never leaving her loom as she smiled.

“We shall tell them it’s the silk from the mulberry blossom fluff that they’ll see clinging to the trees.”

“The silk of dragon’s beards,” Mee chimed in.

“Of ki-lin manes,” said another girl, and the others laughed and nodded. They made up more: the threads came from unraveled snow flakes, from the heads of virgin orphan girls or from the most delicate peacock feather’s veins. Their work went on tirelessly that day, as autumn light painted the room lavender and pale gold and they made up magic and laughed. Only Li Shui went quiet after some time, as if pondering, again, where the thread truly came from.

The men from the west didn’t stay long. They paid gold and horses for bolts of dyed and un-dyed silk cloth and several mulberry seeds to take home and ‘grow’ their own silk, as they thought they could. Each of the weavers as well as the tenders of the mulberry groves were rewarded for their ingenuity with a feast and pearls for their hair.

Mee saw Li Shui’s face growing pale as winter came upon them and began to worry again.

“Li Shui,” she asked over the looms as the first snow flakes fell outside on the stones of the courtyard. “Are you ill?”

“No,” she murmured, lifting her dark dove’s gaze to Mee, and smiled. “Just tired. I’m very tired.”

“You are ill,” Mee insisted. “You should rest. You’ll make no beautiful cloth if you’re ill.”

“No,” said Li Shui, continuing to weave. She had begun a new length of cloth and this one seemed different, this one seemed to shimmer more than the others’ on their looms, as the cocoons had once shimmered when Li Shui sang. “No, I must finish this one first. Then I’ll rest.”

“All right,” Mee said, but her brow cramped from frowning at her the rest of the day.

Li Shui didn’t come to supper that night, and Mee wasn’t sure if she ever came to bed. When she and the other weavers entered the house the next morning, Li Shui was there ahead of them, weaving. As far as Mee could tell, she hadn’t gotten much farther on her piece, as if she had unraveled any imperfect rows and begun again.

“You’ll rest today?” Mee asked, sitting beside Li Shui at her own loom.

“When it’s done,” Li Shui said, soft as a moth’s wing fluttering, and her eyes never left her work.

So they worked in silence again, until Mee could stand the chilly quiet no longer. It wasn’t snowing outside but the world was gray and cool, still, sleeping and dusted with frost.

“Tell me why this one? And it has no pattern. What are you making?”

“It will be my masterpiece,” said Li Shui, finally looking to Mee with the slightest smile.

“Oh,” whispered Mee, and looked at the plain cloth again. Li Shui was already seeking mastery? Of all of them, perhaps she was ready. As Mee watched the cloth it didn’t look plain but warm, shifting, shimmering. “Tell me why this one will be your master piece?”

Li Shui paused in her work, and ran her fingers down the perfect, completed part of the cloth. “In my months back in the First house, I raised these worms. Then I went with them to the Second house to tend their cocoons. I took them to Third house myself to boil, and unraveled their threads with my own fingers. There were so many…but the master weaver let me, and so I did. These creatures and I, we have done all this together.”

Mee was silent for as long as it took Li Shui to return to her task, and the clack of her loom made Mee start up and begin her own work again. She thought to say something to comfort Li Shui, but she was smiling again, even humming as she worked. At last, hesitantly, Mee sang the words that Li Shui had made up so many months ago.

“Come with me and weave with me, we will make cloth to make kings weep…”

She saw Li Shui smile and her lips moved to sing along. Now they added new words, words that sang of the mulberry trees, of dragon’s beards, secrets and dreams.

Li Shui wouldn’t be taken from her loom, so finally Mee began to bring her food and drink but had to jam her loom to make her stop and eat. Her body was growing thin and pale in the gray, sunless winter light. When they lit the lamps, the perspiration on Li Shui’s face and pale sinewy arms made her seem to shimmer.

* * *

The day the cloth was done, all the grounds of the Houses smelled of spring blossoms about to burst forth. Delicate green had replaced snow around the ponds and fish leapt from the waters in the warmer air to feast on hatching insects. The first day of spring was a blessed day to begin or finish any task. The pale dawn sky filled every windowed room of the silk houses with silver light. A girl flew into the sleeping room to wake Mee and all the others, for the master weaver had found Li Shui first and sent the message to all the houses.

“It’s done! Li Shui’s cloth is done, and the most perfect in the world. The master weaver is going to present it to the emperor today.”

The girls flew from their beds and groggily tugged on clothes, some backwards, stumbling, combed back their hair and rushed to the Fourth house. Li Shui was wrapped like a worm in a cocoon in her own cloth, asleep and pale. The girls laughed and dropped to their knees to feel of the cloth, wanting to see it before the master weaver took it away.

There was no pattern, no color, and yet every color as a pearl is every color. Mee knelt quietly beside her sleeping friend and touched at the cloth reverently. It shimmered under her touch, as a moonbeam would in the night, as the half-lit edge of a cloud in day or a slant of sun through water. Mee lifted the cloth to her nose and breathed deeply. It smelled of mulberries, of the oil of ten red-flame lamps and of boiling water, of the sweat on Li Shui’s palms. It smelled of love.

“Li Shui,” Mee murmured, caressing the new master weaver’s cheek. Li Shui’s eyes fluttered open, lashes like moth wings.

“It’s finished,” she said, hugging the impossible cloth around her.

“Yes,” Mee said, and hugged Li Shui close to her. “It’s finished. The master weaver is going to present it to the emperor.” She laughed, happy to see a peaceful smile on Li Shui’s mouth. “I’ll be surprised if he doesn’t want you for a bride – but even if not, oh, you will be sung of! You are the greatest weaver in the world, and always will be.”

“Not alone,” said Li Shui, sliding fingertips over the cloth. “I didn’t weave this alone.”

“Come rest now, please?”

Li Shui consented and Mee took her from the giggling, gasping weavers before the master weaver returned. She walked slowly, lightly; Mee expected her to sag from weariness but she moved as if she felt very light or felt nothing at all. She paused at the doorway of the sleeping house.

“No. I think I’ll walk and…clear my mind. Then, rest.” She turned and suddenly closed her thin, strong arms around Mee. Mee, baffled, hugged her carefully in return, afraid to crush her in this delicate state.

“Let me walk with you.”

Li Shui was silent for a long moment, then drew back, appraising Mee with her dark eyes, dark eyes filled with a startling sorrow. “Very well,” she said softly.

With nothing more to say she turned, her feet still bare, and walked. Mee followed her, her chest tight with misgiving. Why this sadness? Lost in her own musings, she didn’t realize they had passed again through the Fourth house and Li Shui was gliding down the stairs into the Third house. No one was working yet. The vast boiling chamber sat empty, but the water ever boiled. It took too much time and fuel to let the water cool and then bring to boil again.

“Li Shui…”

Mee paused when Li Shui turned, all sorrow gone from her eyes now, and gently touched Mee’s lips to silence her. “Dearest friend. You’ll keep your promise?”

“Promise?” Mee whispered, bewildered.

“You’ll marry Huo, and be glad?”

“Yes,” Mee said, reaching up to grip Li Shui’s wrist. “You’re frightening me. Please…”

“Teach your daughters the song we sang.” Li Shui stepped away, easily shaking off Mee’s grip as if she had a new, secret strength. She walked toward the first massive vat of boiling water, humming softly as she loosened her clothes.

“Li Shui!” Mee sprang forward and then tripped as Li Shui cast off her clothes and threw them in Mee’s path. As she untangled herself, Li Shui climbed the ladder and let down her long black hair. Mee cried out and surged up, throwing off the tangle of Li Shui’s clothes. “No!”

Her shriek echoed across the empty chamber. The last she heard and saw of Li Shui was a glimpse of her face as she cast a look over her shoulder, dark eyes bright.

“I’ve given my thread,” she whispered, and even as Mee threw herself up the ladder, Li Shui turned flung herself into the boiling water. Mee slipped down from the ladder and clutched Li Shui’s clothes to her, weeping, shattered, as Li Shui had once wept shattered over another precious sacrifice, and she knew at last what Li Shui had known.

When she managed to still her tears she rose, folded Li Shui’s clothes and climbed the stairs. She must find the master weaver and tell her that their precious Li Shui was gone.

The weavers wept, shocked and baffled. All the houses wept and went in silence for three days. Why? was the wail throughout the houses. Why would Li Shui have done this? Mee couldn’t bring herself to speak, though she knew the answer. A cold chrysalis wove itself around her heart.

The emperor came on the third day after, demanding to know the one who had woven the perfect cloth so that he could reward her. The master weaver broke the mourning silence to greet him as Mee and the other weavers rose from their looms to kneel in his presence. They were still so cold with grief that none of them could even feel awe of the emperor.

“Our Li Shui,” the master weaver began, her voice quivering in a way that Mee had never heard before, “Was taking trays of cocoons to the boiling water, when she slipped–”

“No!” Mee’s cheeks burned as disbelief flashed through her, then anger that shattered the cold cocoon around her heart. “That’s a lie! I was there.”

The emperor and the master weaver looked to her and she ducked her head down before lifting it again boldly, and then stood up to meet the emperor’s gaze. The master weaver drew a sharp breath and the emperor lifted his hand slowly to stop her, watching Mee’s face as she spoke again.

“Li Shui was heartbroken to know that we must sacrifice the silk worms to take their strands.” Mee clenched her fists, feeling as if the whole room of weavers trembled on her behalf, trembled like moths. Her grief and outrage kept her own voice steady. “She gave her greatest gift, as they do, and then chose to die as they die, so that we might honor them as we’ve honored her, so that we might all know and honor each thread, each life, each sacrifice, as Li Shui did.”

The emperor, who held the precious cloth in his arms even now, rubbed it slowly between his thumb and forefinger while he watched Mee, then looked around the silent room and at the face of each weaver, and finally the master weaver.

“Is this true?”

“Yes,” she answered quietly, but didn’t look up. The emperor turned his gaze to Mee once more.

“Then, this we shall do – this morning, and evermore. For Li Shui. We will remember her as our own silk moth.”

Then before their eyes the emperor knelt, laying the cloth before him. Mee sank back to her knees and bowed her head again as the other weavers bowed their heads, even the master weaver, to honor those who had gone. After a moment of thundering heartbeats passed, the emperor rose, took his perfect cloth and left them.

Mee was the first to raise her head. The other women watched her, and she felt a new sternness in her jaw. The cool morning light picked out the anxious sweat on her brow and arms, and she shimmered as she stood.

“Back to work,” she murmured. Then she began to sing. “Come with me and weave with me, we will make cloth to make kings weep…”

Jessica Owen grew up writing, painting, running wild on a ranch and finding other ways of making the imagined real. This passion took her to theatre where she worked for several years, touring and toiling in professional companies in the Northwest – still writing all the time. A native Montanan, she now resides in North Carolina with her sister, two dogs, and a rat named Sam.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?

Ideas come from all places – history, science, beautiful images, odd names or far away places. Delving into the world and history and nature makes my mind explode with possibilities, and the treasured “what if” question. An image forms, then a question – and as I answer it, the story is born.

0 comments:

Post a Comment