Venezia Nova, or New Venice

by Rob Wills

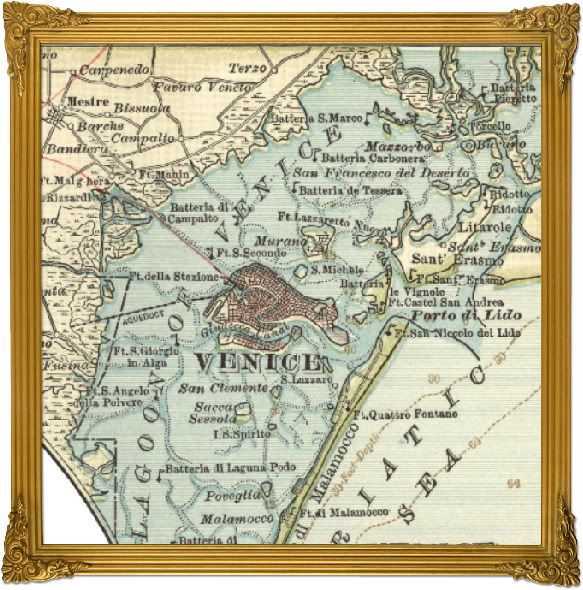

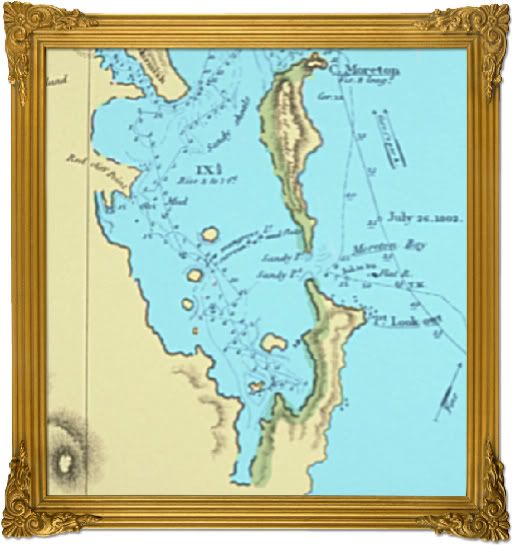

Author's Note: This piece of alternate history arose from the close resemblance I noticed between Venice's lagoon and Moreton Bay near Brisbane, Australia.

Now that certain matters have become common knowledge due to that map of one Ortelius in this year of our Blessed Lord 1570, I have been instructed to make an account, a secret and private (and alas brief) account, of the settlement called New Venice. We know this Ortelius – correctly Abram Oertel – and watch him, and his work, closely. On his map are three countries, Beach, Lucach and Maletur, within the territory of Terra Australis Nondum Cognita – The Southern Land Not Yet Known. On the flank of this Not-Yet-Known-Land Oertel writes: Vastissimas hic esse regions etc. "Here lie the incredibly vast regions described by those travellers M. Polo the Venetian and Lodovico Varthema" (and who today knows of Varthema, that Bolognese – apart from myself?).

It is known that the merchant traveller M. Polo visited the far land of the idolater Kublai Khan. It is known that Polo told of his travels in his book Description of the World, vulgarly called Il milione. It is known Polo says in his book that after taking leave of the great Khan he sailed south but contrary winds held him for five months at the island of Java Minor, preventing him from continuing westward.

It is known that in the year of our Blessed Lord, 1324, back in Venice and with death due to visit him in his native district, the sestiere of Castello, Polo claimed he had revealed hardly half of what he knew of distant lands.

It is not known that Council of Ten received specific denunciations that Polo had withheld information of the highest importance to the Most Serene Republic. It is not known that the Council interrogated Polo regarding information that, during the five months his fleet was delayed in Java Minor, one ship had in fact detached itself from the squadron and sailed east and south, some say to the land of Lucach, some say to the land of Maletur, some say to the land of Beach.

Under certain encouragements from the Council of Ten, Polo did not deny this. Indeed far from denying it, he said he had given a full account of Lucach in his "Description of the World". He respectfully directed Their Excellencies' eyes to the chapter that relates how a south-easterly course from Java Minor brings one to the large and rich province called Lucach, part of Terra Australis: "Its inhabitants are idolaters. They have a language peculiar to themselves and are governed by their own king, who pays no tribute to any other. Gold is abundant to a degree scarcely credible. Elephants are found there. Here they cultivate a species of fruit called berchi, in size about that of a lemon and having a delicious flavour. That country is wild and mountainous and is little frequented by strangers."

Their Excellencies observed they were familiar with this passage, but doubted that Polo was doing anything more than repeating such fabulous tales as travellers tell to astound and impress. For themselves, which means for the Republic, they wanted, demanded, the truth. The old man said indeed he had not told the half of it, and if he had related the whole truth who would have believed him? He confessed that the giant animals of Lucach were not elephants at all but hairy beasts the height of a Swiss Guard with the shape of a monstrous rat and the forward movement of a toad, or a frog, which is to say in great leaps. Had he told the truth that would rightly have been regarded as fantastic. And how did he know of this monster? Because he had seen these creatures himself.

With further encouragement Polo gave full bearings and sailing directions for landfall in Lucach, and was glad to yield up certain sea charts and portolani of that coast. He was also pleased to assist the Camaldolese monks on Murano to prepare charts even more detailed. He died soon after, in this same year of 1324, and the Council of Ten approved his burial without the door of the church of San Lorenzo in his own sestiere.

Venice being busy with other affairs, not least the impudence of the Genoese and other upstarts, all the papers and charts in this matter of Lucach were confined away in the greatest secrecy in the naval archives deep within the Arsenale. There they could not be seen, and especially not by Petrus Vesconte, that map-maker of Genoa.

It is known that a great disaster befell the Most Serene Republic in the years 1347 and 1348, when one of our own galleys brought the plague to our islands, and that only some forty thousand Venetians survived from what had once been more than one hundred thousand.

It is not known that at the height of this catastrophe the Doge Andrea Dandolo and the Council of Ten decreed in secret that as the Republic was in train to die out to the very last man, woman and child, provision must be made to save some who could, if necessary, start the city anew. In short – and short I must be, I have been given no permission to tell this history in full – a gathering of sailors and shipwrights and artisans and builders and military and notaries and, Yes, a score or more of courtesans (it was not fitting that gentle women be subjected to such an enterprise), and two priests and a band of drummers and trumpeters were held for a quarentena on the islet of San Lazzaro. Those who did not die were then sent by sea and by land and by sea again to find Lucach.

The chroniclers of New Venice tell that the very squalls and tempests that had once delayed Polo now swept them south and east through the Oceanus Indicus and on, until, with only five vessels remaining, they were left battered and hard pressed in a vast unknown sea. And before they could catch their own breath a great blast of wind from the north-east drove them landwards.

Our flagship, the San Marco, most sails blown out and the hull taking water, only with difficulty crested a double line of breaking waves. Due to my great skill and fortitude, and with the help of the Almighty, we made the safety of the lagoon, and with deep thanks dropped anchor in the lee of a sheltering island. It was shaped like a cupped hand and gave us protection from the battering wind. This was on the Feast Day of San Lorenzo in the year of Our Lord 1350 and I called this the isle of San Lorenzo. None of our other sail were in sight.

So Vitale Vidal, the Governor of the expedition, wrote (or rather did his scribe). To run, too fast, too fast, through the pages of his journal I can relate that the next day three more ships arrived together, having made entrance to the lagoon through another, wider channel to the north.

They found fresh water, they began their colonia, they made an uneasy peace with the natives (I leaf through fragile old documents in cautious haste – this is no way to write history). Here is the Governor's summary at the end of the first year of settlement, dated 10 August 1351, the Feast of San Lorenzo.

Polo said there is gold in abundance. There is no gold (Note to Self: should I mention this so ... inelegantly, so bluntly, so early?) (Second Note to Self: Should I mention it at all?) (Third Note to Self: Reconsider when fair copy is made). [Marginalia in a different hand: No fair copy was made, only this foul draft survives].

A survey of the land, and the sea, is well under way, to the north, to the south, to the west, and of the two great littoral islands, Pellestrina and Lido. The lagoon and its islets have been described in full. The great river that waters it, the Brenta del Sud, has been navigated and charted to its upper reaches (Note to Self: Perhaps better if the river were to be named after some leading figure in the world of public affairs, for example the River Andrea Dandolo? For further thought).

We have seen Polo's giant Swiss Guard rat toad (we call it Swiss Toad but the natives call it boogal) and we have eaten Swiss Toad. The taste is like goat. But we are Venetian and the seas are rich in fish. There is a small whale that lives in the water-grass of the lagoon and the natives put it to many uses. I have appended a word-list of the natives tongue. [Marginalia: No such list can be found].

The Governor's report continues with a list of Items: Order; Agriculture; Towns; Church; Itineraries; Health; and so on (there was also an item Carnival, but this had been struck out). However there are no entries under most of these Items, except for Towns, where he writes:

There is stone for quarrying. In the middle reaches of the Andrea Dandolo/Brenta del Sud there are cliffs that can provide good material for the masons (Note to Self: No need to mention that all the masons have died – the carpenters say they can work stone).

The report includes a large map of New Venice, showing the amount of territory the New Venetians had surveyed in a year. As always, when I study maps of New Venice and see the great lagoon, the two long sheltering islands to the east shielding the small, settled islands within, I am astounded by the resemblance to old Venice. But whereas our islands are in the lagoon's north, in New Venice this was the opposite, as only befits the reverse of the world, the islands there being, in the main, in that lagoon's south.

To my joy I have been given unfettered access to the most secret archives in order to write this history, to my despair I have been told my account of New Venice (to be produced in one original and ten copies) will be read only by the Council of Ten and then, the copies destroyed, the original will join its sources and all will be returned to the archivio segreto. The sources I use – journals and reports and maps and letters and scraps of paper – all are kept in a handsome, iron-banded, double locked chest. I have one key, the Chief Secret Librarian (a most worthy, helpful, generous, learned and sharp-witted man) has the other. His kindnesses to me are immeasurable.

Here is a private paper written in his own hand by notary Enrico Contarini, also compiled at the end of New Venice's first year:

The banks of the Brenta del Sud are patched with seasonal encampments of the natives. Many fine cities, towns and villages could line this broad river, but with our small numbers we consolidate New Venice on our islands in the lagoon, the foremost being San Lorenzo. Two others are permanently settled, Sant'Elena and San Zan Degola. Being three districts in all we have gone but a half measure and have only a terzieri, yet from understandable affection for our distant home we continue to call them sestieri.

We are Venetians, we live best surrounded by water.

The question of crime: We have gibbets, each island has a gibbet, but these are more to encourage than to punish (I for one do not want the corpse smell following me in each sestiere). And in any event, while we might willingly rid ourselves of a dishonest mouth and stomach, we cannot afford to lose the strong back and the useful arms and legs nourished by that stomach. Our Governor proposed a prison on the island dedicated to Sant'Elena (named with affection for our true home) but there was no enthusiasm for the waste of such fine ground. It has a good eminence commanding the mouth of the Brenta d/S.

Naval Captain Ordelafo Orseolo, a coarse man notorious for his unguarded tongue, openly said only a fool would waste such a fine island to house criminals. When Vitale Vidal heard of this he swore that he would have Sant'Elena as a prison, but did nothing further. Of course. He is a man who blows hot and cold, cold and hot.

Other papers tell me that the island of Sant'Elena there was so called because it shared the shape of the same-named island here in our true Venice, which perhaps to their eyes it did – eyes sadly fogged with the mist of yearning for an old, familiar life. As for the third part of the terzieri, the Governor was moved to write, it seems in his own hand, on the back of a chart of this inshore island:

San Zan Degola (in our Venetian tongue) – the name is a foolish caprice of Captain Orseolo, a man quite lacking in piety, who joked that the island looked like a head severed from its shoulders, namely the coast of the mainland close by. Not to mention this locality's bright red clay – the "blood" from the "beheading" visible on both "head" and "shoulders". A silly conceit, but the name has stuck. He named it so on the second feast day of St John the Baptist, 29 August, when the loss of the saint's head is observed. Naturally a small chapel to St. John has been built there. Addendum: The Captain was even more pleased with himself (if that is possible) when he discovered that the natives already call the island Goocheemudla, which, he speciously claims, sounds like San Zan Degola. But he went too far when he proposed (how seriously I do not know) that we might use this native name. I firmly rejected such a ridiculous idea. Firmly.

In my box of archives there are many letters that are indeed but one extraordinarily long letter written by the courtesan Francesca Monegario to a sister in disgrace, her friend Olimpia, whose dwelling here in true Venice, according to the direction carefully noted on each, was: "Sestiere of Castello, parrocchia of San Zanipolo, the house with the carving of the sword and the book where the Rio di S. Giovanni Laterano meets the Rio della Tetta." Clearly a neighbourhood of courtesans! Nonetheless I can say, objectively as a scholar, that this woman Francesca Monegario, despite her shameful calling, writes with wit and colour, and I confess that from time to time I am glad she is so prodigal with her words.

My dearest Olimpissimissima,

What to say of this place where we have – I was going to say "ended up", but I refuse to believe, to think, to even consider that I will "end" here! It is not New Venice, it is not "old" Venice, in short it is not Venice at all. What it is is sand. Sand sand sand sand sand. It is sand everywhere. My dear I have so much more sand than I have ever wanted or needed. In my hair, in my clothes, dusting the very few small objects I possess, in my very person!

But enough of sand. I will speak of it no more. We live on the main island, San Lorenzo. Think of some primitive little hillock just above high tide in the far reaches of the lagoon (the real lagoon) where a fisherman and his family have set up summer camp. A fishing camp with a crude hut of one room and walls of rough timber (imperfectly fitted), reed roof and a cooking fire outdoors, fishing nets everywhere, boats and sails and oars and balers and hooks and shells and the smell of fish everywhere. Welcome to San Lorenzo!

The company here is, you might imagine, quite limited. At the top of the column, wreathed not in laurels but the nastier plants that flourish here (there are so many!) is our Governor. A man whose opinion of himself is so high that he need not worry what others may think, which is just as well as others are of a different mind. A man of tall stature (and like all such he believes his height translates into superiority in all things), I have to concede his person is not unpleasing. When not engaged in making decisions of state – and we have already learned that not making decisions is very much part of his humours – he has an engaging manner about him, and eyes and mouth that tell he is man not unfamiliar with pleasure. Of course I do not speak from personal knowledge. Yet. Beyond his fine robes, not quite so fine now, behind his "official" face, so stern and forbidding, some kindness, some tenderness might perhaps be found.

The Governor holds decisions delicately at arms length between his fingers, examines them from all sides, then drops them and walks away, while the Captain makes too many decisions. Like all sea captains he believes that the imperative is the only manner of speech. Do this. That. Stop. Go. Come. Run. Wake. Sleep. He barks like an angry dog all day and much of the night. And when I tell him so, like any dog he only barks some more. So I call him good dog and pat him and offer him some titbit (so to say) and he settles to that. To our mutual comfort. Oh, and when he eats he gnaws and chomps with table manners not fit even for the deck of a ship of war. Unsightly battle wounds have disfigured him everywhere. This is known to more than me, as Dame Modesty has no lodging in our New Venice (I think she must have drowned on the voyage here or else died of shock on arrival). From living so long in close quarters aboard ship, from still living crammed together on these damned sand islands where even tho' we wash separately in the lagoon, men at Adam's Beach, women at Eve's, we all know each others' bodies as well as a mother knows her baby. I tell a slight untruth – the Governor of course bathes shielded by his servants holding up an old sail.

And there is the Notary, a sober and learned man, with somewhat cold blood in his veins, even in the heat of New Venice. He stares, he examines, he observes, he notes. I suspect he already has a list of our weaknesses longer than the priests who hear our confession. He seems to have wit but is too mean to share it, old miser. In this purgatorio we are all starved for entertainment, for amusement, and a man with a sharp eye and a quick tongue is highly valued – or would be if we could find one. You know I love nothing more than to chatter of people and their foibles, their deeds and their do's and their don'ts. How I miss it!!

I will stop here before my great tears of sorrow for myself blot and blur all I have written so far. I do not want to have to write it all again!

With muchest love, your dearest friend Francesc-amica.

Dated this Feast Day of St Giles (the hermit!)

Venezia Nova

Sestiere of San Lorenzo

The fourth fishing hut on the left as you follow the path from Merciful Cupped Hand That Saved Us Bay (the hut that stinks worst of fish guts)

That was her first letter and I treasure it. By which I mean of course that I value the perspective even a wicked mind and tongue and pen can provide to better assist my understanding of New Venice. Her description of the "fishing camp" has a greater ring of truth than many of the Governor's fine and elaborate accounts, where one might be led to believe that the very Doge's Palace had been transported in the same way as the Holy House of Loreto, namely through the skies, and laid down on a patch of sand atop the isle of San Lorenzo in the southern seas.

How Francesca Monegario thought this letter these letters would ever be read by her friend Olimpia I cannot say. But a person, like myself perhaps, has some understanding why she would be moved to confide all things, all, to a sympathetic piece of parchment. Yesterday I found my steps had taken me through the city to that house with the carving of the sword and the book. Several centuries on but still my thoughts, my thoughts ... No, there is no profit in this.

At the end of the colonia's first year comes mention of the sealed orders, and the secret order, that came to, to contaminate New Venice. There were a number of orders, but I have done my best to untangle which order was issued by whom, and to whom, and why, and what each order was (this is not as clear as I had intended). Apart from their large wax seals, the only aspect they shared was that each was marked: "To be opened by the named holder on the first anniversary of arrival in the Land of Lucach."

The Governor had one such instruction, issued to him by the Council of Ten. He was ordered to establish a trading agreement with the King of Lucach so that Venice might gain access to the gold of this kingdom. Any other riches and trading goods of value that came to the Governor's knowledge were of course to be included in this agreement. And any agreement need not be confined to the King of Lucach should there be other kings, other kingdoms, whose possessions would enrich Venice and Venetians (the Council took pains to spell out all possibilities so that Vidal could be in no doubt of what was expected of him). By order of the Council, His Excellency Vitale Vidal was raised to Ambassadorial rank and as a Plenipotentiary Extraordinary granted full powers to treat with the King (any king) on behalf of the Most Serene Republic of Venice. His new status was to be displayed by a heavy silver chain, embellished with a precious jewel, to be hung round his neck (the value of this symbol of office was noted by the keepers of the state Treasury and Vidal was adjured to hold the chain in secure keeping).

The most senior of the two priests also opened a sealed command, although here the wax was stamped with the seal of St Peter, his orders having come from Rome rather than Venice. Giovanni of Dorsoduro (an apt place of origin, the papers reveal him to be a hard-backed, stiff, unyielding cleric) was told that he was both to keep close watch on the Venetians to make sure there was no back-sliding from the faith and the precepts of Rome, and to bring the heathen natives to the true religion. The first of these orders would surprise no one, it being no secret that Venice and Rome hold each other in mutual suspicion. As the popular saying drolly has it – we Venetians believe in San Marco whole-heartedly, in God to a sufficient degree, and in the Pope not at all.

The Captain, Ordelafo Orseolo, was the third man to break the seal on a confidential letter on 10 August 1351. His orders were brief and to the point. To ensure the preservation of Venice – the real Venice – the colonists were to hold their quarantine abroad for one hundred years from their arrival in Lucach. Then they and their descendants could return. That was all. Any breach would result in the painful death of those who flouted the order, and eternal ruin for any and all family members, to the third remove. And the Captain was charged with the duty to make sure that – in the event he was not still alive in 1450 – his successors carried out the order. Should he fail, ruination would befall his family to the sixth remove. He was at liberty to make these proclamations.

The Captain, not a man comfortable with his letters, was moved to scrawl in a large hand on this order:

100 years generous indeed as we expect in 1450 the youngest of us will have lived 112 and I will be 139. well the best we can hope is that the plague in Europe will have left no one to carry out barbarous commands. of the other order the most secret order I am at a loss I will keep it close held the closest and consider

This "most secret order" was an insidious plague that entered New Venice at this time. But more of this later, perhaps.

A leather pouch in the archive chest contains disparate pages where the Notary, who took an interest in the natural world, kept notes he wrote on divers topics. Despite Francesca Monegario's unkind view of him, I felt some warmth for the Notary, a man who could use his Logic skilfully without losing regard for his fellows:

The mangroves, like the natives, are all around us but we see more of the mangroves. These amphibious trees are great colonisers, certainly better than we. They send out fleets of small green pods to claim and settle tracts of mud flats. They are everywhere in the lagoon, fringing the islands, concealing the entrance to the Brenta d/S, and clinging to its banks. We could well take example from their quiet tenacity, but for us it is a hard lesson to learn.

There are signs of the natives wherever we go, footprints, old fires, piles of shells. And in every direction we see the columns of smoke rising high from their fires. One of the natives, Toonbar, a man with whom I converse so we can learn each other's language (altho he does better with mine than I with his) showed me an ingenious fish trap at the place called Goompee on Pellestrina (Goompee is where we have built a modest chapel to San Marco). In shallow water by the shore the natives have set low rock walls to make a large square enclosure, so that when the tide recedes fish are held within the walls for harvesting. I was delighted, and told him of the valli da pesca back in our old home lagoon that use dykes for the same purpose. And the long, tapering fish cages they make here from reeds have the shape of our own cogoli. He was less amazed than myself, taking it as natural that such ways of fishing would be universal among men – and I do believe now he is right to think this way.

We struggled, I struggled, up steep sandy tracks to the highest point on Pellestrina, a hill they call Bippo Penbean – a name which, despite the Governor's distaste for native words, has nonetheless gained currency among us. We gazed in silent pleasure at the lagoon and its islands shining with gold and silver alchemised by the late-day sun. In the far distance the smudge of purple trees, the thin strings of smoke, and all around us the insistent buzz and hum of summer in New Venice. At dusk the bats we call pipistrelli fly out in their millions and overflow the sky.

Letter of Francesca Monegario, dated Feast of St Porphyry of Gaza, 1352:

So much good news!

I have eaten berchi! It is like ... nothing I have tasted before. Smooth yellow outer skin, great oval seed inside and between skin and seed the sweetest golden flesh that makes the most delicious mess and leaves stringy reminders between the teeth for days! We all gorge and grow drunk on Marco Polo's berchi.

We have sung and danced our first carnival in New Venice!! With masks of painted bark and songs that marry the music of old Venice and native chanting of the New. The natives can take up a tune or a dance faster than any music master from Paris. This carnival is the first and only time we and they have been at ease in each others' company. I hope for more.

The Governor's second year summation is an odd document:

New Venice, Feast of San Lorenzo, 1352

Great progress was being made in treating with the native kings. There are many, but, as ordered, I have been assiduous in establishing harmonious contact with the great chiefs. However my untiring efforts have been seriously impeded by the loss of my Ambassadorial chain of office. When I say loss there should be no misunderstanding that I misplaced it. I am pursuing this serious breach of order and have [etc etc].

There is much, much more in the same vein. Indeed the whole lengthy report deals with nothing but the missing chain.

Letter dated Feast of St Euthymius the Younger 1352 from Francesca Monegario:

The Governor's latest grand notion is a colony up river, opposite the stone cliffs. Knowing his humours, all agree with him and of course nothing gets done. When the Governor speaks of this or that plan I hear the Captain grunt rudely, or see him flick his eyes and shoulders heavenwards. I asked him later what he thought of a land-bound village and he replied, "It may well sing the Gloria for some, the Genoese I would certainly think, but not for we Venetians – we are people of the islands, of the lagoon." I laughed. I have grown fond of his rough wit but his irreverent mention of the Gloria brought on a bout of melancholia as I recalled the voices singing in rich, splendid San Marco. I yearned so for my old life and wept for my present my past my future, for us all.

But to happier matters! The bird song here is the sound Venetian glass would make if it sang – full of brilliance and trills and twists and turns. There is a particular bird, a small sharp-shaped one, with such silken bright colours that we smile every time we see one. Its nest is a burrow in the sand!

Then the Captain was killed, his lifeless body found behind a sand dune. At first the natives were suspected but the Notary, who was charged to investigate, found evidence suggesting it was not one of them but one of the colonists who had done this thing. A scrap of paper clutched tight in the Captain's clenched fist had remains of a wax seal and all believed that this was from the "most secret order", but no sense could be made of it. The Notary's investigations were fruitless, no one being brought to justice for the crime.

As for the Governor's Ambassadorial chain, it was, to my knowledge, never found.

As for who killed Captain Orseolo, I am satisfied I have deduced who committed that crime. But, and I say this without spite or malice, because I have insufficient space at my disposal here I will not reveal who the criminal was. To do so in a true and convincing manner I would need to set out my Logic in full. Unfortunately I am denied the words so to do.

The history of New Venice did not proceed peaceably, but where and when does history ever do that? There were more deaths, murders even, many on San Zan Degola, and there are sombre hints in the documents that these were due to the infamous "most secret order." As always, rumours rushed to fill the gaps left by lack of knowledge.

But life stumbled on, as it does, and there were marriages and births and deaths. In great contrast to Francesca Monegario, I will say nothing of her marriage – she devotes countless letters (some 23 in all) to her swain (a man of no account), his courtship, her joy at her nuptials and matters too degrading for an important report such as the one I am writing here. There is no more to be said on this. It is of no account whatsoever.

Nonetheless I have to say, because my history demands it, that her marriage was fruitful and she bore eleven children, of whom four survived; including her last born, a son, who was baptised on St Genesius the Actor's day in 1375. He fathered a daughter, Caterina, born in 1414, but he did not live to see her an adult. Francesca Monegario herself died a "respectable" old woman of ninty-two in 1426, and her grand-daughter Caterina buried her with pomp on the cemetery island of San Michele. This Caterina married Domenico, a descendant of the notary Contarini, and together they governed New Venice, with what authority I am sure I cannot say, both sadly abusing the title of Doge.

Domenico Contarini writes as follows somewhere around the year 1440 (alas, precision with dates had fallen into some confusion in the most remote colonia of New Venice and I have often had difficulty in matching their dates with the correct ones):

Our relations with the natives remain ... unresolved. Over the years there have been killings on both sides, reprisals and truces. And the n the same again. And there have been lives saved by both sides – some party in danger rescued, a lone traveller nursed to health from snake bite, struggling children plucked from the lagoon by a saviour who saw only a child, not the set of its hair or its skin colour. For all that we are still separate. They do not accept us here, and, truth to tell, if the Turks were to build their dwellings on an island in our old home lagoon in full view of the mighty church of San Marco ... well.

As the wheel of the years turned, the colonia expanded and contracted like a bellows (does this read well? – the wheel and the bellows?). From time to time new settlements were established. some even on terra firma, along the banks of the Brenta d/S. But then they would shrink back again to the lagoon. In the last years the New Venetians were consolidated, confined even, only on Sant'Elena, the other islands having been reduced to seasonal or overnight camps shared with the natives. On one of these out islands – Pellestrina, I believe – during a fishing party's overnight stay, the last warning came.

A young native man, name not given, who was admiring the paintings glorifying the walls of the chapel of San Marco told one Agostino, also an art-lover it seems, that he should know there was continual talk of the Black Swan dance. Caterina then explains in her careful, small hand, that this unlikely bird, the black swan (proof if ever it was needed that all things are reversed on the underside of the world) was notorious for aggressively defending its territory, for driving out intruders. Thus when the natives were enraged against some encroacher they would paint their bodies black and their noses red to resemble, to be, this fierce bird. This man told Agostino that red ochre was being gathered in great quantity from Goocheemudla. Smoke could be seen up and down the coast from a great number of fires, many more than usual.

To hasten through to the end game, the colonists decided they must leave immediately, standing no chance against overwhelming numbers. Their departure had been long planned for they believed the year 1450 to be fast approaching. But not all wanted to leave for there were those who would stay. But whether all left or whether some stayed I cannot say. No list was kept of travellers on the vessel New Marco Polo. Certainly there is none in the records I have seen. A small number of New Venetians made landfall in India, finding refuge on the Malabar coast where it seems there are rivers and lagoons and backwaters and sand dunes – a dear, familiar landscape for old and new Venetians. St Thomas is revered there. These survivors – how many? one, two, more? there so many frustrating gaps! – made contact with the Portuguese and lied and bluffed and false-promised their passage home. Here they were of course, and quite rightly and properly, interviewed by the Council of Ten. Let us trust they were then peacefully and happily reunited with distant family members who would succour and cherish them. Let us trust this happened, for no more is heard of them. Their records – all these papers and charts and letters and sketches and dead leaves spread out before me – do survive to this day.

Here ends my meagre history of Venezia Nova. The Council of Ten, in their far-sighted wisdom, have decreed that I must limit my account to some few thousands of words, but in truth one hundred thousand could not do it justice.

Venice, Feast Day of St Cyriacus the Recluse, 1570

Signed,

AS THERE IS NO NEED FOR THIS NAME TO BE KNOWN, IT HAS BEEN REMOVED BY ORDER OF THE COUNCIL

* * *

Rob Wills says: I am quite old and content to be so. I'm glad I studied foreign languages at high school (where I had to) and at university (where I chose to). Languages are the best key to other peoples, other cultures and – not least – other times. I married young and we lived and studied and worked abroad before settling back home in Australia. Our children were born in the UK and Ghana. My daughter recently saw a performance of King Lear and said that, unlike most productions of Shakespeare, the fool was actually very funny, and he looked and behaved like me. This pleased me.

What advice do I have for other writers of historical fiction?

Do your research, but don't overdo your research. I have a lot of embryonic stories, novels, film scripts, that never developed into anything because I kept thinking they "need more research". It's a pity, because so many good ideas stay just that, good ideas and nothing more. So be sensible in your research on an historical subject: remember that you only need to know enough, you don't need to know everything.

4 comments:

i like it this writer has alot of promise

wow! i didnt get it at first, but then when i did i had to read it again, which i really enjoyed. i got an extra experience out of it. i'm going to look our for more of his stuff

deBeirs62, Ma

this is a cleverly-written, intelligent piece that revels in, rather than shows off, its cleverness. i really enjoy the "documenta" form of it, and it makes "alternative history" twice as attractive as "real" history, which as we all know is already pretty cool *grins*

knows both places well,and the time and the eternal human condition.

Post a Comment