Chapman

by N. T. Brown

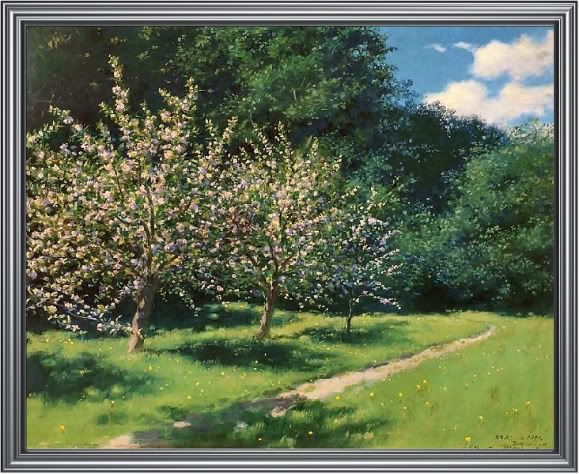

Chapman, in the schoolhouse, stares through the open window at the orchards. On a distant hill, the boughs move in the breeze as though a gentle hand is guiding them. And indeed, Chapman thinks, there must be one—the hand of God. No movement without purpose. Even if he doesn’t know what that purpose is.

The schoolmaster’s rod slams down on Chapman’s open book, and the boy nearly jumps out of his seat. Everyone in class is looking at him. The schoolmaster’s oversize nose with its tufts of black hair sticking out of each nostril dips down to within an inch of Chapman’s face. His mouth opens to reveal his rotted tooth. “Perhaps, Mr. Chapman, you think you can find that sum out in those fields?”

On the blackboard, a multiplication problem. Chapman scratches an answer onto his paper and the schoolmaster sighs, goes back to the front of the class. “You forgot to carry the two,” he says. On the board, he works the problem out to its end. “How,” he says, whirling back around, “will you ever be able to transact business if you can’t make computations? How will you keep yourself from being cheated? I know your father, Mr. Chapman. Do you think, when he takes his crops to market, that he doesn’t know the exact amount he should receive?”

Chapman blinks a few times.

“How will you make money?” the schoolmaster asks.

I don’t care about money, Chapman thinks.

Outside, boys and girls pour into the late afternoon sun. Someone shoves Chapman from behind. “Hey, big eyes!”

Chapman turns back.

“Hey, hoot-owl, where’d you get those eyes? They’re the size of dinner plates!”

“And you’re skinnier than a scarecrow. I thought your father was a farmer. Don’t you have enough food?”

“You leave him alone!” Nancy Tannehill, brown hair, blue eyes, freckles, stands between them. “Look at your own snub nose. You’ve got no right to talk!”

The boys lean back, thumbs hooked in pockets. “Let’s go,” they laugh. “Leave these two lovebirds alone.”

“We are not lovebirds,” Nancy calls after them. Then, quietly: “Where are you going, John?”

“Out to the orchard.”

“What for?”

Chapman kicks a pebble with his bare toe. “Sit under a tree, read my Bible.”

“Can I come? Will you read to me?”

On the hill, his back against a trunk, Chapman reads from the book of Matthew: “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about what you will eat or drink, or what you will wear. Is life not more important than food, and the body more important than clothes? Look at the birds: they neither sow nor reap nor store away into barns, and yet your Father in Heaven feeds them. Are you not more valuable than they?”

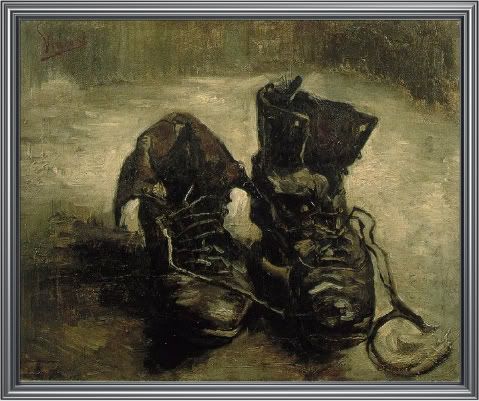

“Is that why you don’t wear shoes?” Nancy asks.

Chapman holds his finger on the page.

“You’re not poor,” she says. “I know your father can afford shoes. But you won’t wear them. Why?”

“They cramp my feet,” Chapman says.

“Let me feel them,” Nancy says. Lying on the grass beside him, hair splayed like pine straw, she twists around to examine his soles. Her tiny hands rub them up and down, a sensation Chapman has never felt. “They’re like leather,” she says. “They’re harder than any shoe.”

Chapman smiles.

“You’re a strange boy, John Chapman,” Nancy says. She starts to weave blades of grass into a design. Chapman lets an ant climb up his arm.

“I had the dream again last night,” he says.

Nancy sits up. “Tell me.”

“My mother in bed, coughing blood. Choking on her own blood. Begging me to help her. Blood coming out of her nose.”

Nancy squeezes his hand, looks into his eyes, says nothing.

The sun drops behind the hill and darkness falls over the orchard as though someone covered it with a blanket.

Chapman gets to his feet. “We should go,” he says.

The schoolmaster’s gelding is tied outside Chapman’s house. Autumn’s first chill slices through the air. Chapman steps through the dark like a cat and peers through the window, where, by light of a candle, his father and the schoolmaster sit talking.

“It’s not that he’s incapable,” the schoolmaster says. “He just doesn’t apply himself. He’s a daydreamer.”

Father smokes his pipe, strokes his beard.

“And he’s a good lad,” the schoolmaster says. “I don’t mean to imply that he’s not. I just worry about his future, is all.”

Father exhales. “Perhaps Johnny isn’t cut out for school. He’s more of an outdoorsman. Quite a talented horticulturalist—an arborman if I’ve ever seen one. In fact”—he leans forward and says something too low for Chapman to hear.

The schoolmaster rocks back with a loud snort. “He communicates with trees? Listen, sir, I graduated second in my class from William and Mary, and if you think for a second I’ll believe such twaddle—”

“And I fought with General Washington,” Father says menacingly. “While you were nestled by the fire with your books, I was freezing my balls off at Valley Forge. So you just watch what you say when you enter my home.”

The schoolmaster stands up. “I came here out of concern for the boy. I can see that my efforts were misplaced. Goodnight, sir.”

Chapman flattens himself against the wall as the schoolmaster brushes past. Halter bells jingle as the gelding whinneys and then trots away down the road. Chapman can’t go inside now—his father will know he’s been eavesdropping. Instead he walks around to the barn. He enters silently and sees, by starlight coming through the slats, his brother Nat stretched out on the hay, pants around his ankles, jerking himself furiously.

“Nat,” Chapman says.

“Hold on,” his brother says, and continues, until he makes a gruff noise. Then he wipes himself on a piece of sackcloth, buttons his pants, and sits up.

“Why do you do that?” Chapman asks.

“Because I have to do something.”

“You’re eleven years old,” Chapman says.

“Why don’t you do it? You think it’s wrong?”

Chapman leans in the doorframe. “No. I don’t know.”

“Well, it’s not. I don’t care what your Bible says.”

“The Bible doesn’t say anything about it, as far as I know.”

Nat stands beside him and claps him on the shoulder—with the same hand, Chapman thinks, the same hand he was just using. “You’re not normal, brother,” Nat says. “Those big eyes of yours see too well in the dark.”

Together they walk back to the house. Father hasn’t moved from his spot. “How do the orchards look, son?” he says as they enter.

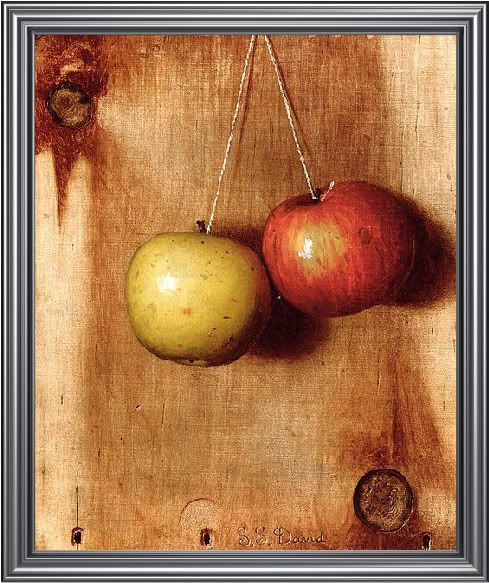

“Ready to harvest,” Chapman says. “Those apples will drop and rot soon, if nobody gets them.”

The old man tamps down more tobacco. “How would you like to quit school this fall and help out with the harvest?”

“Yes,” Chapman says.

“I’ll have to speak to Mr. Gordon about it. I’m sure he could use the help.”

“What about me?” Nat says. “Can I drop out too?”

“A noble effort,” the old man says. “But you must finish primary, at least. When you’re Johnny’s age, then we shall see.”

That night, lying on the top bunk as Nat snores beneath him, Chapman has another dream—not the usual one, not his mother’s death. This time he dreams of Nancy Tannehill in the woods, rubbing his feet, and then his calves, his knees, his thighs—and then—

He awakens violently to a sticky mess in his sheets. Falling back into sleep, he imagines Nancy as his wife, and the two of them, accompanied by a gaggle of children, armed with ladders, harvesting the orchards together, as a family….

* * *

Chapman moves his ladder in a circle, around the scaffold of branches, and drops the hard fruit into a sack. Voices of other pickers carry through the woods. Songs of the Revolution, still lodged in men’s minds nearly twenty years later. Songs of freedom, expansion, of endless possibility. They also speak of lands to the west—Ohio, Indiana, Illinois.

Old Gordon walks by and comments on Chapman’s bare feet. “Jesus, son, it’s getting nippy out here. You’ll get frostbit.”

Chapman smiles down at him. “Not me,” he says.

Gordon sighs. “I have some bad news, John. A few of my investments this year didn’t pan out.”

Chapman blinks a few times.

“I can’t pay your wages this year. Don’t worry, you’ll be compensated—but not before the New Year. I’m sorry, John.”

Chapman nods. The money itself means nothing, but he had planned to use it on a ring for Nancy Tannehill. He even chose one from the selection over at the silversmith’s. Now he will have to wait until spring.

That evening he walks with her along the hill, under a pink and orange sky. Nancy runs her hand over the low wooden fence. A flock of geese floats past, heading south for winter. “How are things at school?” Chapman asks.

“There’s a new boy from Finland,” she says. “His name’s Kai.”

“Finland. That’s a long way off. Wonder how he ended up here.”

Nancy balances on top of the fence with her arms outstretched. “You won’t be back, will you? Even after the harvest. You’re never setting foot in that schoolhouse again.”

“I can’t say.”

She jumps down. “Can you plant me an apple tree? In my backyard? Just one. I’d like to have my own apples.”

“You won’t get apples with just one. Apple trees don’t self-pollinate. You need at least two in order to get fruit.”

“Well, two, then,” she says, and skips ahead of him.

“In the spring,” Chapman says, and thinks: The spring. It will happen in the spring. Until then I will wait. I will hibernate. I am a bear.

On Christmas day, Father gives Nat a new knife, and Chapman a tattered copy of The Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. “That book has seen better days,” Father says, “but I thought you might be interested.” He and Nat eat quail while Chapman chomps roasted chestnuts. Snow drifts keep them indoors. In the evening, Chapman studies the book and can scarcely believe what he reads: there is a New Church, with new beliefs. The Second Coming has already arrived. Nature belongs to God now. Charity will be rewarded. There will be no Armageddon. Everyone, regardless of religion, can go to heaven.

It’s early April, first spring thaw, by the time Chapman gets his money. Old Gordon delivers it up to the front porch. Twenty-five dollars. Chapman could have sworn the other pickers got twice as much. He tries to remember the rate per bushel and how many bushels he collected, but can’t. Gordon rides away and Chapman goes straight to the silversmith. The original ring he wanted is gone, but he finds another, slightly tarnished one, forks over twenty-two of his twenty-five dollars, and starts down the road to the Tannehill house.

Nancy lives down a muddy lane with a stone wall on one side. A crow perches at the far end, cawing as Chapman approaches. He kicks through slushy snow, jostles the ring in his pocket.

At the house, no one answers. It’s Saturday, and Mr. Tannehill is likely out with his horses, but Chapman can’t imagine where Nancy and her mother might be on a grey day like this.

He strolls around back to survey the yard. Where would Nancy like her apple trees planted? They need a high spot, or else standing puddles will rot the roots. Apples are delicate. The least little thing will kill them—or at least render them fruitless.

But the yard’s highest ground already has a stand of birches. Perhaps they’ll have to come down. Chapman loathes the thought of destroying trees, but if apples are what Nancy wants….

“John!”

Chapman whirls around. Coming out of the woods in a long blue dress and a hat with a flower sewn onto the front is Nancy—hand in hand with a tall, serious-looking boy. Chapman’s fist closes around the ring in his pocket.

“What are you doing out here?” Nancy says. Her cheeks pulse red from romping in the snow.

“Looking for a place to plant those apples.”

“Oh, aren’t you sweet!” Nancy says. Then, to her sturdy friend: “I told you he’s the sweetest boy I’ve ever met. Kai, this is John; John, Kai.”

The Finn’s hand feels like granite against Chapman’s. He doesn’t smile, but says in a deep voice, “Hallo.”

“Where is everyone?” Chapman asks. “Your family?”

Nancy prances from foot to foot, almost hopping with energy. “They’re all in town. Oh, John,” she squeals, “no one knows—you’re the first to know—Kai just asked me to marry him! We’ll be married this summer!”

Chapman blinks a few times.

He recalls Nancy at the schoolhouse last year, calling out, “We are not lovebirds!”

Kai nods but still does not smile. Nancy unlocks her hand from his and flashes Chapman a ring—not a better one than his, either. “Isn’t it lovely? Aren’t you happy for me?”

“I didn’t know you were planning marriage so soon.”

“Neither did I.” She wraps an arm around the Finn’s waist. “Kai just surprised me. It’s funny how sometimes the thing you want most is right under your nose and you can’t even see it!”

Chapman shakes the Finn’s hand again, mutters something about coming back with some saplings when it gets warmer, and starts back down the road. The same crow sits on the stone wall, and this time two more join it before they all flap away.

On the way home, Chapman stops at a house he doesn’t know. An old washerwoman with a kerchief on her head answers the door. “Excuse me, ma’am,” Chapman says. “I found this ring on the road outside. Someone must have dropped it.”

The woman cocks an eyebrow and says, “Why, yes, I surely did. I’ve been looking all over for this. Bless you, son.”

“You’re welcome.”

“Hey,” she calls, and Chapman looks back. “Don’t you need any shoes?”

Chapman smiles and waves, waves like it means nothing to him, like he can’t even feel it.

Announcing his departure to Father turns out to be easier than he expected. He catches the old man in the dark, returning from the outhouse, and corners him there so Father won’t see his tears. He mentions nothing about Nancy Tannehill but says he’s tired of Massachusetts—he’s heard about open, untamed lands to the west—Ohio, Indiana, Illinois. Father doesn’t seem surprised, but rather acts as though he knew this was coming. “You don’t have a horse,” he says when Chapman finishes his speech.

“I can walk,” Chapman says.

“You need a destination. It isn’t wise to just wander aimlessly, with ‘the Ohio territory’ as your only goal.”

“I’ll know my destination when I get there.” No movement without purpose, he thinks. “God will put me where he wants me.”

“How will you live? Where will you sleep?”

“You know me, Father.”

“Take one of my guns. Then, if you get desperate, you can bring down a deer, or at least a quail.”

“I would never use it, Father, and you know it.”

The old man puts a hand on his son’s shoulder. Chapman studies his father’s features in the scant light, knowing his father can barely see him at all. “You will take shoes,” Father says. “That much I insist upon.”

“All right. I’ll take shoes.”

“I want to come too,” Nat says in the darkness beside them. Chapman nearly jumps out of his clothes, but again, Father seems unsurprised.

“I told you that you have to finish primary first.”

“But Father,” Nat says, stepping into view. “What’s a real education? Sitting at a desk all day, or exploring the wilderness? Didn’t you learn more under General Washington than you would’ve if you’d stayed home where it was safe?”

These lines sound rehearsed—as if his brother, too, foresaw him leaving. What did they know that he didn’t? “I don’t remember inviting you,” Chapman says coldly.

“You can’t stop me.”

“You two would leave me here?” Father says, yet behind his words Chapman hears a certain pride.

“I’m going tomorrow,” Chapman says, by way of warning.

Nat spits onto the icy ground. “Shoot, I’m ready to go tonight.”

By the middle of the third day Chapman’s shoes dangle from his hands by their strings. He tosses them to a traveler going the other way, a man with a bindle over his shoulder, who catches them against his chest. “Barely worn,” Chapman calls.

“Thanks,” the man says, and Chapman continues on his way.

“Are you some kind of idiot?” Nat says. “We could’ve gotten at least two dollars for those.”

“And do what with two dollars?”

“Anything. Buy food.”

Chapman laughs. “There’s food all around us.” As if by providence, they come upon a blackberry thicket and Chapman plucks off several clusters.

“It was stupid anyway,” Nat says. “You’re not going to last long, you keep doing things like that.”

The forest thickens as they head west. Horses and carriages become less frequent, until the boys find themselves alone on the road for nearly a week. Something unfolds inside of Chapman, something he never knew was there—he imagines an accordion, or a piece of paper unfolded to its full size for the first time. His strides become easier, his heart lighter. The more distance between he and Nancy Tannehill, the better.

“Feels like I can stretch out now,” he says.

Nat, cooking pot clanking on his back, says nothing.

* * *

One warm evening they come to a farm carved out of the forest. A man in sweat-drenched overalls stands in the yard drinking water from a pail. A little girl waits beside him, and when he drains the pail, she takes it and scampers away. Chapman and Nat each hold a hand up as they approach.

“Well, you two look tired and dirty enough,” the man says.

“We are,” Nat says.

“Where you headed?”

“For the Ohio territory,” Chapman says, and the man bursts out laughing.

“This is only New York. You’ve got a ways to go.”

“We’re moving. We’ve got all summer to make it there, before it turns cold again.”

Newly-planted fields stretch out behind the house. Chapman recognizes the tiny green shoots of young corn. “We can work,” he says. “For a bed and a meal. We can do whatever you need.”

“Today’s work is done,” the man says. “I wouldn’t charge a man for a plate of beans and a spot on the floor. Welcome to a bath, too, if you want it.”

As the sun sets over the fields, Chapman finds himself naked in the back yard with Nat, taking turns in a wooden barrel filled with cold water. Chapman borrows a razor and shaves his beard, which has grown thick. At dinner he sits at the table with slick hair and a fresh-looking face.

“You’ve lost ten years,” the farmer says. He shovels potatoes into his mouth. The house has only one dark room, with a fireplace at one end and a curtain separating the farmer’s bed at the other. His wife sits silently alongside three young girls. Candlelight throws shadows across the walls. Nat lowers his head and clears two plates before anyone else can finish one.

“I’m sorry we didn’t get to help out,” Chapman says. “If we’d been an hour or two earlier, we could have earned our keep.”

“We could do something tomorrow,” Nat says through a full mouth.

“I wouldn’t keep you boys. I imagine you want to get a full day’s travel. Every day counts if you’re trying to make Ohio by fall.”

“There must be something we can do,” Chapman says. “Does your family keep any books around? I could read something to these ladies. I could read from my Bible.”

Nat gives him a sharp look.

“It’s not much, but it’s something I could do to show my gratitude.”

“You some kind of preacher?” the man asks.

“I think it would be lovely,” the wife says—her first spoken words that night. Every head turns her way. A long pause.

“Well, there you have it,” the farmer says.

After the meal, Chapman sits by the fireplace and reads from the book of Matthew. The women sit before him, while the farmer leans against the back wall and smokes his pipe. Nat, on the side, seems just as rapt as the females. Chapman realizes that his brother has never heard him read like this before. He did it with Nancy Tannehill a thousand times.

“Then the Lord will say to the righteous, ‘Come, take your inheritance, take the kingdom prepared for you since the beginning of time. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me water, I was a stranger and you took me in, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you cared for me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ Then the righteous will answer, ‘Lord, when did we feed you, or give you drink? When did we take you in and clothe you? When did we visit you?’ And the Lord will reply, ‘I tell you the truth: whatever you did for the least of my brothers, you did for me.’”

The wife’s face trembles on the verge of tears. Behind her, the farmer says, “You’re one of those Swedenborgers, aren’t you?”

“I am of the New Church, yes,” Chapman says.

“What?” Nat says.

“You think everybody goes to heaven,” the farmer says. “No matter what they do.”

“Well,” Chapman says. “The New Church teaches that everyone can go to heaven.”

The farmer points his pipe. “You’re telling me a Mohammedan, or some Hindoo in the jungle somewhere, is going to heaven the same as me and you?”

“Christ welcomes all,” Chapman says. “Even those who call him by a different name.”

“Do you have any extra Bibles?” the wife asks. “I can’t read, but maybe”—she looks over her shoulder—“Henry, maybe you could read to us now and then?”

“I don’t have any more,” Chapman says. “But you can keep this passage.” Carefully, he tears the page out and hands it to the woman, who stares at it for a moment before folding it into her pocket.

The farmer nods a grudging respect.

The next morning they rise with the farmer, shake hands in the dark, and leave without breakfast. Chapman can sense his brother’s discomfort after last night’s scene. Nat wasn’t expecting anything like that. They walk in silence most of the morning, and pass through a cluster of buildings in the afternoon—not enough to call a town. More like an outpost.

One of the buildings is a cider mill. Its open doors reveal an apple-crusher bigger than a carriage. Pulpy brown pomace covers the ground around it. A few men lean against barrels in the shade. “Now’s our chance,” Nat says, “to know if we’re going the right way.”

The mill workers are affable, but they give the boys one stringent piece of advice: take the river. “Walking all the way to Ohio is a fool’s quest. You might get lost, you might run into a damned bear. Why, there might even be some Iroquois still out there. Take the Susquehanna, get there fast and safe.”

“Can’t you get no horses?” someone says. “Even if you had to share a horse?”

“We don’t have any money,” Nat says.

“What do you do with all this pomace?” Chapman asks. Nat rolls his eyes.

“How hungry are you, son?” The men all laugh. “Those leftovers are no good for eating. We just throw it away.”

“Good for fertilizer, though,” Chapman says. “And full of seeds. Can I take it?”

The men laugh again. “Sure, scrape up as much as you want.”

The Susquehanna is another week’s trek. During the walk, Chapman works seeds out of handfuls of pomace, dropping the gooey pulp along the trail. He hears the river’s whoosh one night as he and Nat are settling down, and the next morning they reach it—not too wide, but swift-flowing with early-summer runoff. He and Nat stand on slippery rocks and peer downstream.

“What are we supposed to do?” Nat says. “Swim?”

Chapman points to a fallen tree. “We could make a dugout.”

“From that scrawny pine? You think that would work?”

“Worth a shot,” Chapman says.

“But we don’t have a hatchet,” Nat says. “Or an adze, or nothing.”

“You’ve got Father’s knife—that should clear away the bark, at least.”

“Hell, we could just straddle this thing and ride it down the river like that.”

Chapman starts to denounce such a foolish plan, but then recognizes his brother’s sarcasm. He rubs his chin with his hand. “We could burn it out,” he says.

“Hey now,” Nat says.

They take turns stripping the bark, a task which consumes most of the day. Nat tears into the work with a zeal that surprises Chapman. In the afternoon, they flip the log over and, using sharp rocks, cut an outline. Chapman files down knots in the trunk. He boils some oatmeal from his pack for their lunch. The sweet smell of fresh-cut wood hangs in the air. By nightfall, the tree is ready to be gutted.

“Let’s wait until morning,” Chapman says. “If we try to do it in the dark, we might burn up the whole log.”

The next day they pad the sides of the trunk with wet moss and ferns, and start a slow burn down the middle. Chapman keeps the cooking pot full of water nearby. As the middle section crumbles into ash, Nat scrapes away the blackened chunks until, late in the day, the log begins to resemble something like a canoe. “By god, this might actually work,” he says.

When they finally push the log into the water, Chapman realizes the flaw. “The bottom needs to be flat. This thing is going to capsize.”

“Nah,” Nat says. He stands waist-deep and rocks the log back and forth. “Might be a little wobbly, but I think she’ll hold.”

They shove off with their rear ends wedged into the crevice and their feet hanging out the sides. Chapman looks back and notices the cooking pot still sitting on the bank. “Wait,” he says, and slides back into the water. Nat thrusts his oar—a long pine branch—into the riverbed to stop the boat, while Chapman swims to shore, plunks the pot onto his head, and swims back.

“That looks terrific,” Nat says when Chapman climbs in. “That’s the best hat I’ve ever seen.”

Chapman smiles and, to humor his brother, wears the pot the rest of the day.

In three days the boat dies. Chunks of the log start to break off, and capsizing becomes more frequent. Eventually, with all their gear soaked, the boys admit to each other that they are basically clinging to a piece of driftwood. They wade ashore, and after clambering through some brush, find themselves at the edge of a homestead.

Chapman knocks at the door, but no one answers. He and Nat wander around back. An old man kneels over a wooden bench, whittling something with a knife. The blade flashes in the sun. Several figurines line the table before him. Yellow fields lay untended, rising to a hill covered in poplars. A flock of birds wheels around the sky, then disappears in the woods. “He’s no farmer,” Nat says. “Look at these fields.”

“Excuse me, sir,” Chapman says. “We’ve been traveling for a while now—whereabouts are we?”

“Just outside Freeport,” the old man says. “About three days from Pittsburgh.”

“Pennsylvania?”

“That’s right.”

Chapman gestures to the fields. “This your land?”

“Sure is,” the man says. “I’m a veteran—served under General Knox, fought at Trenton and Yorktown. They give me this land for my service.”

“Our father served under General Washington,” Chapman says.

“Is that so? Does he know about the land grants? The government is giving all veterans a parcel of land—a hundred acres—provided they can prove that they served. Can your daddy prove it?”

“He has his discharge papers,” Nat says.

“Pennsylvania’s full, though—they’ve opened up the Ohio territory now. Won’t be long before all that land is grabbed up too. If he wants to claim his, he better get moving. Me, I don’t even plow mine—I’m a woodcarver, not a bean-picker. I earn my living selling these figurines.”

“We’re headed for Ohio,” Chapman says. “How far is that?”

“Never been that far. I hear it’s a farmer’s paradise. But the hunters and trappers, they usually keep going west, into the deep woods, to a land called Wisconsin. Nobody knows how far that stretches—it could go all the way to China. We’re just scratching the surface of this continent. No telling what’s out there.”

Chapman eyes the section of hill beneath the poplars. “That would be a perfect place for an orchard.”

“Apples?” the man says. “I haven’t eaten an apple in ten years.”

Chapman reaches into his satchel and comes up with a handful of seeds. “I can start some for you. You won’t get fruit for two or three seasons. But once they mature, you should get apples every year.”

“You’ll plant me an orchard—for what in return?”

“Nothing,” Chapman says, but at the same time Nat says, “A place to rest.”

The man laughs. “You’ll have to show me how take care of the saplings. I don’t know the first thing about apple trees.”

“It’s easy,” Chapman says.

The next day they walk into Freeport proper. Ramshackle buildings flank a muddy street, where horses and people scurry back and forth. They pass a large white building with pillars out front, labeled CITY HALL. Nat gets excited—he presses his face against every shop window. “Look at that candy!” he says. “If only we had some money—if only you hadn’t given away those shoes.”

Chapman, meanwhile, only sees opportunities for trees. “Right here, between these buildings,” he says. “That would be a great place to plant two or three apples. The drainage here is great. I don’t think it’s too shady, either….”

As they wander through town, Nat says, “You know, it wouldn’t be so bad to settle in a place like this.”

“Really?” Chapman says. He thinks of this town as a novelty, an interesting way station, but not a permanent residence.

“Don’t you get tired of sleeping in the woods with the snakes and bugs?”

“I guess not,” Chapman says.

A mustached man hawks tickets for a fair, to be held that night along the river. Paper lanterns have already been strung up; workers are assembling tents and booths. “Get your tickets now,” the salesman says. “Only a nickel. You’ll see one-of-a-kind acts, marvels found nowhere else on God’s green earth—magic and mystery—hurry before we’re sold out!”

“Isn’t there some way we could get in on credit?” Nat asks.

“Cold hard cash is the only credit, son.”

Nat walks away grumbling, and he and Chapman find a tree to lie under by the riverbank. Skiffs push off from shore, loaded down with cargo, operated by men who laugh and shout from raft to raft as they zip downstream. “We could hire on to one of those boats,” Nat says.

“I doubt they’d hire me,” Chapman says. He closes his eyes, and when he opens them again, Nat is gone. He left his pack behind, which means he didn’t abandon Chapman—he just went to explore the town. Chapman eats an old biscuit he’s been saving and, to kill time, reads from the book of Proverbs. Down by the water, workers set up the fair. One of them walks over and leans against the tree, wipes his face with a rag. “You better get in there behind that screen,” he says. “I bet they don’t want people getting a free glimpse before the show starts.”

“Excuse me?” Chapman says.

“You one of them, aren’t you?” the man says. “The ones in the show?”

Chapman blinks a few times. “I’m just passing through.”

“You’re not in the show?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Chapman says.

“I just figured with those eyes of yours,” the man says. “And how skinny you are. Never mind, kid.”

The afternoon grows hot, and Chapman brushes mosquitoes away from his ankles. The fairgrounds lay in deep shadow, the sun just an orange glow in the west, by the time Nat returns. He has a young girl with him, maybe thirteen or fourteen. “This is Lizzie,” Nat says. “She got us free tickets.”

“How’d you manage this?” Chapman says.

“My ma gives me money,” the girl says.

Reluctantly, Chapman rises and follows them down the bank. The paper lanterns, strung from tree to tree, rustle in the breeze. As they walk, Chapman takes Nat by the shoulder and whispers, “Where did you meet her?”

“Outside one of the stores,” Nat says. “She has a great big family. She said we can spend the night at her house.”

People congregate around the tents. Chapman hands his ticket to the same man who spoke to him under the tree earlier, but this time the man isn’t paying attention. “No re-entry!” he calls to the crowd at large. Chapman wades into a throng of people, and they move down a long row with tents on either side. Nat and Lizzie duck into one, and Chapman loses them. He works his way over to a tent and pokes his head through the flap. There, on a makeshift stage, is some kind of monster—a person so mangled and deformed that it can scarcely be called a person. Chapman quickly retreats, and realizes that each of these tents contains some abnormality, some poor, freakish being. He doesn’t care to view the rest, but stops with his head bowed for a moment and wishes the blessings of Christ on all of them, indeed on everyone here.

Up ahead, Nat and Lizzie emerge from one tent and scamper across the aisle, into another one. At the end of the row, close to the water, sits the main attraction—a large cat of some sort. A rotund man with a top hat and waxed mustache claims it to be a tiger captured in Sumatra and brought to America on a perilous journey. The animal paces its cage with glowering eyes. It looks well-fed, but Chapman pities its life. He slips out of the fair, back onto the moonlit riverbank, and starts walking. To be different is one thing. To be caged is quite another. He fingers some loose seeds in his pocket.

At a high spot, he pushes them into the spongy soil.

Sometime during the night, Nat finds him under their tree. “Come on,” his brother says. “We got a roof over our heads tonight.”

Chapman is comfortable where he is, but shrugs on his pack and walks two or three miles across Freeport to Lizzie’s house—an old British-style mansion, shaded by oaks, probably built twenty years before the war, now handed down to a family of women. “Their father died,” Nat says. “And now they just roam and do what they please.”

Lizzie’s feet are black with dirt as they walk up the lane. “You don’t wear shoes, either,” Chapman says. The girl smiles up at him.

The house is cavernous—Chapman figures the original owners were Loyalists and the place has been ransacked, refurbished, trashed again, handed down through various parties. Lizzie leads them by candlelight to a room with some blankets on the floor, beneath a window. Whispers come from other rooms and Chapman gets a sense of people shuffling about. “How many sisters do you have?” he asks.

“Eight,” Lizzie says. “We always got to tend mama. She’s too fat to get out of bed.”

Someone down the hall coughs loudly.

“What happened to your father?” Chapman asks.

“Kicked by a mule,” Lizzie says.

Chapman expects Nat to bed down beside him, but Lizzie leads him away to another room and he doesn’t come back. The moon floats halfway across the window before it occurs to Chapman why. His little brother, eleven years old, is dominated by urges Chapman has felt only rarely, and in passing. By moonlight, he studies Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: “All other sins are committed outside the body, but the man who sins through sex sins against his own body. Do you know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit? You are not your own—you were bought at a price. Therefore honor God with your body.”

Nat comes to him before dawn and says: “I’m staying here.”

Chapman sits up. He is utterly dumbfounded. So much time passes before he answers that Nat thinks he’s still asleep, and shakes him: “Hey! Wake up. I’m not coming with you today, you hear me?”

“I hear you,” Chapman says.

Nat puts his hand on Chapman’s shoulder. “I’m sorry,” he says. “But I’ve found something here that I can’t walk away from. Lizzie and I are going to get married.”

“You’re only eleven—”

“I turned twelve last month. Don’t you know your own brother’s birthday?”

“Nat,” Chapman says, but before he can say more, his brother says:

“Johnny, you know how you’re always searching for something?”

“No,” Chapman says.

“No? What’s so special about Ohio? Why are we going there? Why do we live like animals? What are you looking for, Johnny?”

Chapman blinks a few times.

“Listen—I found what I was looking for. These girls don’t have a man around here. I can help them. You could stay too—maybe you can marry one of Lizzie’s sisters.” Nat looks hopeful, then adds, “Lizzie’s the oldest, though, so you’d have to wait a few years.”

“You know I can’t do that,” Chapman says.

They sit for a moment, and then Nat dives forward to embrace him.

By first light he is back across Freeport, back to the river road, which he walks all morning as the sun rises behind him. Birdcalls fill the air. Travelers on horseback tip their hats. To Chapman’s right, flatboats skim lightly down the river.

He doesn’t stop to eat until dark, when he boils some oatmeal and mixes it with nuts and berries from his pack. The first night without Nat, the old dream returns: Chapman’s mother, lying in bed coughing blood, blood coming out of her nose, until Chapman runs screaming from the room—but this time, when he jumps awake with a shout, no one is there to reassure him. No one snores softly beside him, or even down a hall. He is alone, and chilly, lying on a bed of pine needles in a glistening forest. There is a certain purity in this.

Dear Father,

After a long journey, I have reached the Ohio Territory and am happy to report that it is a beautiful country. There is much farmland and wildlife here. Autumn is nearly upon us, and I have completed my journey just in time.

Nat and I parted ways in Pennsylvania—he met a family there and stayed on to help. I’ve been walking alone these many weeks. I wouldn’t have known I was in Ohio, had I not come across a lonely post office, which is where I now sit, in the gloaming, writing this letter.

This journey has been remarkable. People everywhere are friendly and happy to offer help. There exists a spirit of optimism amongst our countrymen that I never knew about. Perhaps you recognize it, Father, from your time in the war—everyone seems to be looking forward to something. I don’t fully understand this but it gladdens my heart to see it.

Ohio is an empty country, but not for long. The rumors of land grants are true. If you show your discharge papers, you will be granted no less than one hundred acres of prime farmland. According to locals, even the native Shawnee honor these grants, and don’t resist new settlers. This could be a splendid opportunity for you.

I do have one request: my Bible is quite worn, with some pages missing, and I would like to have another, if you could send it. You may respond at this address; I’ll likely stay around these parts for the winter. Nat’s address is also enclosed, though I can’t attest to how accurate it is.

If I don’t hear from you before spring, I will leave a notice with the postmaster that you might be headed this way. On horseback, the journey should not take long. I may be somewhere else by then.

You are in my heart daily. I think of you and pray for you often, and trust that you know that I love you very much, Father, and eagerly anticipate a good word from you. Until then, I remain,

Your son,

John Chapman

Moonless night. Chapman—skinny, dirty, with crow’s feet around his eyes and a beard that stretches past his collarbone—sits hunched over a fire with wild potatoes skewered on sticks. Early June, chilly. He’s been in the woods for over a month, and can’t recall the last time he spoke to another human being.

Down the trail, a slight noise. A twig snap, a shuffle of dirt. The smell of another traveler. Chapman’s senses are like an animal’s. Soon a figure emerges from the shadows: long cloak, gun across his back, canteen slung over one shoulder.

“Howdy,” the voice says—high-pitched, like a child’s, and for a moment Chapman imagines Nat, whom he hasn’t seen in fifteen years. “Mind if I share your fire?”

“Sit down,” Chapman says, and the figure enters the circle of light. His face is almost cherubic in the flickering glow. “You want a potato?” Chapman says. “I’ve got plenty.”

“Obliged,” the kid says. “I tried all day to nab a deer but they’re too quick. Or else I’m too poor a shot. You couldn’t get no game, neither? Ain’t there any wild boars around here?”

“I’m not even sure where here is,” Chapman says.

“Why, you’re in Indiana,” the kid says. “Don’t you even know where you are?”

“No,” Chapman says simply. He feels the kid waiting for further explanation, but he doesn’t have one. “No,” he says again.

“Well, hell, you’re on the Ohio border. You’re just south of Fort Wayne. That’s where I’m headed. Where you headed, mister?”

“Nowhere in particular,” Chapman says.

The kid bites into a potato and chews. “My daddy beat the hell out of me two days ago and I’ll be goddamned if I stay around there. I’m going to sign on to fight Indians.”

“Why do you want to fight them?”

The kid snorts. “Hell, you got to fight somebody.”

Chapman blinks a few times.

“You don’t have any meat here, do you?” the kid asks. “Dried jerky or anything?”

Chapman almost says, “I don’t eat meat,” but fears the kid would only react with derision, so he says, again, “No.”

The kid spits into the darkness. “Lean times, I guess. Well, I appreciate you sharing your fire. All right if I bed down here?”

“Of course,” Chapman says. “But I’m about to douse this fire, so bundle up.”

“What? What in the hell for?”

“It draws insects.”

“Aw, they dive right into the flames. They ain’t going to pester you none.”

“That’s precisely why,” Chapman says. “I don’t want to be responsible for killing anything. Even bugs. Christ was against it.”

The kid cocks his head. “Are you crazy or something?”

Chapman takes another bite.

“You’d rather lay here in the damn cold than kill a couple of flies?”

“It’s not that cold,” Chapman says.

“I never heard of nothing like this before,” the kid says.

Later, after the potatoes are gone, Chapman kicks dirt onto the fire so that he and the kid are sitting in pitch darkness. “By god, wait till I tell them about this in Fort Wayne,” the kid says. “You know, I could just as easy go off a ways and make my own fire.”

“You could,” Chapman says. In the dark, he can see only outlines of things—which means the kid can’t see at all. But the kid doesn’t move.

“You some kind of preacher, or what?”

“Sometimes.”

“You know any of them old Bible stories?”

“Most of them, yes.”

“Is it true what they say about the End Times—God’s going to send a wave of fire over the Earth and burn everything up?”

The kid’s voice sounds vulnerable all of a sudden, young and scared lying there in the dark woods. “No,” Chapman says. “That’s not true at all. The End Times have already come and gone. We’re already living in the New Earth. People just aren’t aware of it.”

At dawn, Chapman rises and slinks away through the woods, leaving the kid on his back, open-mouthed, shiny drool running down one side of his face. In the grey light he looks even younger than Chapman thought. He takes a portion of cornmeal from his pack, leaves it beside the kid, and heads toward the rising sun, back into the Ohio territory, a land he has crisscrossed a hundred times, but which always seems to have something new in store for him.

One evening at dusk he rounds a bend and comes face to face with a black bear. The animal has its front paws halfway up a tree trunk, grasping for something, and it jumps back when Chapman appears. The little bob tail twitches. It’s at least six hundred pounds.

Chapman raises his arms above his head and looks the bear directly in the eyes. It gives an agitated growl and backs up a few steps. If he flees, it will chase—Chapman knows this much. So he steps forward, and echoes the bear’s growl right back at it.

They eye each other for a full minute before the bear makes a noise like a dog’s whine, a noise of frustration, as though it’s being pulled back by an invisible hand. It slinks away without breaking eye contact. Chapman keeps his hands raised and walks slowly past, singing an old battle hymn, one of the songs the apple-pickers back home used to sing. Anything to make noise, anything to show the animal he isn’t afraid.

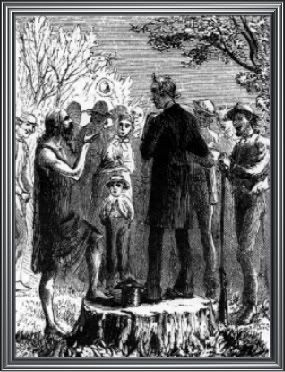

On a ridge, looking down at a stream, he sees an Indian: buckskin clothing, feathers woven into long hair. Over his shoulder the man carries a type of satchel. He kneels down at the stream, cups water in his hands, drinks. Birds flit back and forth over the rocks.

Something inside Chapman says: Don’t pass this up.

So he climbs over a rock and then down the ridge, through the trees, kicking leaves and shaking branches to make as much noise as possible. The Indian leaps up. Chapman stands with his arms outstretched, just as he’d done with the bear—but this time in a gesture of conciliation. The Indian is unarmed.

They stare at each other. The Indian says something in French. Chapman can’t help but smile. He expected a wild man, a savage, but this Indian wears boots, appears clean—and speaks more languages than Chapman does. He says the French phrase again.

“I only speak English,” Chapman says.

“English,” the Indian repeats thickly. “My English not as good.”

Chapman’s heart pounds. “You understand me?”

“Understand yes, not speak as good.” His mouth twists to form the words. “Even my grandfathers speak francois. English, this is something new. But I learn fast.”

“You’re Shawnee?”

“Shawana,” the man says. He touches his chest. “Abukcheech. The little mouse.”

Chapman repeats the name back slowly. “Ah-book-cheech. My name is John.” He isn’t sure whether to offer his hand or bow, so he does both. The Indian squeezes Chapman’s fingers for a moment.

“Do you know where you are?” the Indian asks.

“I think I’m in Ohio somewhere….”

“You are in Shawana lands. This place is not safe for you.”

“I’m just passing through.”

Abukcheech’s face is smooth, cheekbones like boulders under his skin, eyes wide-set and placid. “You are lucky you saw me first. My uncle would have killed you. The francois leave us alone, but you English clear our land, you chop down our trees.”

Chapman shakes his bag of seeds. “I plant trees.”

The Indian peers into the bag and then up at Chapman with a strange glint in his eyes. He mimes eating an apple, and a thrill of excitement shoots through Chapman, stronger than anything he’s felt in years. “Apples,” he says.

“Yes. Apple.”

Abukcheech kneels down and opens his satchel, which is full of herbs and dried mushrooms. Chapman recognizes most of them. He points to cornflower, which eases colds and fevers—the purple petals now crispy and curled up on themselves. “And that yellow one is St. John’s wort,” he says. “That relieves pain.” He names Klamath root, Pokeweed, Skunkweed, stinging nettles, thistles, blackberries, and for each one, Abukcheech provides the Indian name.

They crouch over the sack and Abukcheech holds up a handful of brown mushrooms. “For talk with Great Spirit,” he says.

Chapman pulls out his Bible. “I talk to him through here.”

The Indian takes the Bible and leafs through the pages, though it’s obvious he can’t read. “In Shawana, I am healing man,” he says. He hands the Bible back to Chapman. “You are healing man?”

“I’ve never healed anyone,” Chapman says, and the Indian smiles.

“You are man of Wakan Tanka—of Great Spirit.”

“I call him Christ,” Chapman says. “But I believe we’re talking about the same thing.”

Abukcheech squints at him. “You cannot travel these lands alone. Follow me, I will show you to my uncle. He will grant you passage.”

Chapman blinks a few times. “Lead the way,” he says.

* * *

A cluster of tents around a creek. Horses dip their snouts into the water. Laundered buckskins flap on lines. Women pound flour into thin cakes. Children scamper.

“This is only summer camp,” Abukcheech says. “Temporary camp.”

He leads Chapman to a group of men standing apart from the village. No one down by the creek notices Chapman’s presence, but the men in this group grow animated and shout when they see him. “Wait here,” Abukcheech says, and goes forward to speak with them. One of the Indians, a fierce-looking man with only one eye, gestures wildly and has to be restrained by his fellows. Chapman’s knees shake as Abukcheech comes jogging back.

“They want to see you. Come.”

Chapman approaches the group and bows. The one-eyed man spits at his feet. These Indians are old, older than Chapman, with impenetrable faces. The one who restrained the one-eyed man—a tall, fine-featured fellow wearing a red cap with a feather—steps forward to grasp Chapman’s hand. “This is my uncle,” Abukcheech says. “Tecumseh.”

The man says something in Shawnee and Abukcheech translates: “He says he has heard of you. The Apple Man. You have roamed these lands for twenty years.”

Chapman nods. Tecumseh says more.

“He wants to know why you do not align yourself with the other whites,” Abukcheech says.

Chapman stammers. “I—I travel alone. I don’t align with anyone.”

Tecumseh nods, but the one-eyed man shouts a long slew of watery language and several others murmur agreement.

“This is also my uncle,” Abukcheech says. “Tenskwatawa—the Prophet. He says all white men come from the Serpent, the Evil One, and they must be burned. For him it is great insult that I bring you to this village.”

Chapman lowers his head and says, “I’m not here to fight anyone.”

Abukcheech and the Prophet exchange words. Their voices grow more and more heated, until Tecumseh steps between them. He holds a finger in Chapman’s general direction and says a few words, then walks away. The Prophet, clearly upset, spurts some last invective and stalks in the other direction. The group of men break apart, leaving Chapman and Abukcheech alone on the little rise.

“Tecumseh gave you permission to cross our land,” Abukcheech says. “I knew he would. He knows you are man of Wakan Tanka.”

“The Prophet didn’t seem quite as happy about it.”

“They are brothers—but they will never agree. The Prophet claims all white men are evil. Tecumseh is too smart for that. He knows the difference between the government and a person like you.”

“A person like me,” Chapman repeats.

“There are no people like you,” Abukcheech says, and smiles.

A week later he comes upon a homestead with a young orchard out back, and realizes it’s one he planted four or five years ago. The farm has since changed hands—the new owner a young man in a straw hat who complains to Chapman that he can’t yield any apples.

“You haven’t been pruning enough,” Chapman says. The young trees aren’t even as tall as him, though they should be much bigger by now. “Or you’ve been pruning during the wrong time. If you prune during winter, you’ll get a big harvest the next summer. Prune in the summer, your tree will stop growing.”

“I’ve been pruning every summer,” the man says.

Chapman bends a branch and inspects it. “These might be stunted permanently. But maybe not. See, your branches should be two feet apart. That way the fruit will have room. And your trees ought to have a scaffold shape—these limbs should grow out perpendicular. They should have been weighted with rocks during their first year. Now they’re all over the place. And you have far too many buds on here.”

“I wanted as many as possible,” the young man says. “To sell the leftovers.”

“The fewer the buds, the bigger the fruit,” Chapman says. “Those buds should be six inches apart. Otherwise you’ll get nothing worth selling.”

The man offers Chapman a meal and a place to sleep by the hearth. His log home is bigger than most of the others Chapman has seen in these parts: the man and his wife actually have separate sleeping quarters from their children. The little ones sit rapt as Chapman reads from the book of Genesis—the story of Noah and the ark, something he figures will entertain their young minds. When he finishes, he says, “Remember, it doesn’t matter if the story really happened or not. It’s the lesson that’s important.”

Five little heads nod, and Chapman is amazed—this married couple looks far too young to have so many babies. The woman is skinny as a scarecrow, with large shimmering eyes like Chapman’s. They look so much alike that Chapman can’t stop staring at her, and fears the farmer will get the wrong idea. She might have been his sister.

After the Bible story they eat biscuits and honey—a treat for the children, Chapman surmises, brought out in honor of him, the visitor. He asks the wife: “Do you see well in the dark?”

“Like an owl,” her husband answers. “She can look out the window and see a fly flap its wings a hundred yards away at midnight. It’s those big eyes.”

“That’s right,” the wife says.

“I’m the same,” Chapman says.

“Is that so? Well, I can see it now, though I didn’t notice before. You two have got the same eyes.”

Chapman flips to the Book of Acts, to the passage about Saul getting blinded on the road to Damascus. Carefully he tears out the pages. “Here,” he says, handing them over. “This story always reminds me that true sight comes from our souls, not our eyeballs.”

In the morning, the farmer scribbles an address on a piece of paper and says, “Write to us sometime—I’ll keep you updated on that orchard.”

When Chapman reaches a hill on the road, he looks back. The entire family, man, wife, and children, stand waving to him. He waves back until they’re out of sight.

In the town of Mansfield, at a one-room post office, a group of burly men surround him as he scratches out a letter to his brother Nat. Chapman glances up from his paper. The men cross their arms over their chests.

“You been out in the woods,” they say.

“We know who you are.”

“You been out to Indiana. You seen the Shawnee.”

“I’ve been living in the woods for some time, yes,” Chapman says.

“You know their trails,” the men say. “You know where their village is.”

“No,” Chapman says.

“What do you know about their ways?”

“No more than you, I’m afraid.”

One of the men points a finger at Chapman. “Just mind you know which side you’re on when the fighting comes. If we find that village and you’re in it, you’ll get cut down with the rest of them.”

The men start to walk away, but Chapman calls out: “The Shawnee are angry. They say you’re taking their land.”

The men come back. “They signed away that land to the United States government under the Treaty of Fort Wayne. My Pa fought in the war, so I know. And now these goddamn animals think if they swoop down and kill women and kidnap babies, we’ll just turn tail and run. They’ve got another thing coming. We’ll hunt down every last one of them.”

This encounter leaves Chapman so shaken he can barely finish his letter.

He meets Abukcheech by the stream and tells him how unhappy the settlers are. “They claim your tribe steals babies and murders women.”

Abukcheech casts his eyes down. “This is true,” he says. “I am ashamed at certain things the Shawana have done. But there is no stopping my uncle. When the Prophet speaks, the people listen. They follow him. He says to burn Christian artifacts, we burn artifacts. He says to burn any Shawana who has converted to Christianity—and so we burn people. Now he says all white men must burn.”

“How did he lose his eye?” Chapman asks.

“The gods took it from him during a vision. In exchange he can see the spirit world.”

Chapman doesn’t know what to think of this. “Those townspeople are looking for you,” he says. “Your tribe should just relocate—move west with the others.”

“This has been our home since the beginning,” Abukcheech says.

“The beginning of what?”

“Of everything,” Abukcheech says. “Come, I want to show you something.”

He leads Chapman away from the stream, into a hidden thicket where a black-and-white mare stands silently, her rope bridle looped over a branch. Chapman climbs behind Abukcheech and they trot away through the forest. He hasn’t been on horseback in years and is amazed at how much ground they cover so quickly. Soon they crest a hill where he can see the entire town of Mansfield below.

“We can slaughter them at any time,” Abukcheech says. “Yet we do not, because Tecumseh does not believe in slaughtering innocents. Nor do I.”

“It would be harder than you think,” Chapman says, pointing to the walled fortress, a circle of upright spiked logs toward the back of the town. “They could hunker in there for weeks.”

“We would starve them out.”

“Maybe there’s a compromise,” Chapman says.

Abukcheech sighs. “I once hoped for such a thing. But for the Prophet, there is no compromise.”

“Maybe I could talk to your uncles.”

“You do not understand what you are saying. They will kill you for insulting them.”

“I don’t mean any insult. I just want to prevent a massacre—to either side.”

Abukcheech gives him a hard look. “Why do you not speak to your own people?”

“I’ve been trying for twenty years,” Chapman says. He slides off the mare and Abukcheech wheels her around. The Indian’s face is heavy, melancholy, as he starts back down the trail.

“Meet me at this spot on the new moon,” he says. “If there is a time my uncle will listen, it is then.”

Chapman stays in the town and observes. The men form hunting parties. They arm themselves with rifles, muskets, swords, ropes. They leave at dusk, carrying torches. Chapman, under awnings, leaning in alleyways, crossing muddy streets at dawn, sees them return from their midnight searches. They want blood.

At night he can’t sleep. The nightmare returns: his mother, coughing blood, blood coming out of her nostrils. Lying in a field under an oak, he jerks awake again and again. Never did he think the frontier would be like this, with groups of men hunting other groups of men like animals. Twenty years ago, he felt a spirit of optimism pulsating from this land. Now it’s on the verge of descending into madness. He thought the continent was limitless—but apparently it is not large enough.

He tries to read his Bible, but it’s too dark. Instead he sits with his back against the tree and thinks about his father, the revolution, the orchards, the river, the chain of events that led him to be here tonight, the Earth rotating on its axis.

He thinks of the northeastern beach, which he hasn’t seen in so long.

Abukcheech’s face appears from the shadows, painted red and white. An uneasy feeling churns in Chapman’s stomach. It is the new moon. The fires of Mansfield burn below. “Why are you painted like that?” Chapman asks.

“Tonight we make war. I warn you so that you may escape.”

“You said I could speak to your uncles.”

“If they see your face tonight they will remove it from your body. The Prophet’s blood is boiling. He has the tribe in a rage. Tonight the Shawana kill.”

“You plan to kill as well, Abukcheech?”

The Indian nods. “For you to kill is against your nature. But for me it is different. The little mouse will do what the Shawana require.”

“Your English has gotten better,” Chapman says.

“And still you have learned no Shawana at all.” Abukcheech places a hand on Chapman’s shoulder. “I am sorry to make violence on your people. But the Shawana have a saying: There is time for peace, and time for war. This, John Chapman, is time for war.”

“The Bible says the same thing,” Chapman says.

“Then you understand.”

“No,” Chapman says. He starts back down the hill, leaving Abukcheech’s glowing face behind as though it were the absent moon. “No, I don’t,” he says.

Halfway down the hill, stumbling in fear and disgust, rusted cooking pot clanking on his back, he agonizes. If the Shawnee leaders won’t listen to him, and the white men won’t listen to him, then what can he do? Flee into the forest and allow the slaughter to happen? What would Father do? What would Swedenborg have done? Anything, Chapman decides—anything to stop the killing. He sprints into town, leaping over gullies and hedges, and pounds on the door of the first house he comes to. A man’s voice calls out: “Wilson, I already told you, the damn thing ain’t for sale!”

“The Shawnee are coming,” Chapman yells. A moment later the door swings open and a bearded man—one of the men who cornered Chapman at the post office—says: “You.”

“Get your family inside the fort,” Chapman says.

“Why should I listen to a damn lunatic like you?”

“Get your children behind those walls. They’re going to kill everybody.”

“Everybody but you, I guess,” the man says, but Chapman doesn’t stay to argue. He runs to the next house and repeats the message. The man at this door rebukes him outright.

“I don’t give a good goddamn how many are coming,” he says, and brandishes a long bolt-action rifle. “I’m staying right here.”

“You don’t understand,” Chapman says. “They’ll burn this house to the ground.”

A woman in a bonnet appears. “How many are coming?”

“What in the hell kind of question is that?” her husband says.

“I don’t know,” Chapman says. “But we don’t have much time.”

“Janice,” the woman calls behind her. “Diana. Get your sisters.”

“Now hold on just a goddamn minute,” the man says. But the woman pushes past him, outside with Chapman, leaving the man standing there holding his rifle, with a dumbfounded expression.

“I’m going to tell the Yorks,” she says. “And the Marcums.” She runs down the road with her dress billowing behind her.

“I ain’t never had control of that woman,” the man says in a low, confidential voice.

“If there’s ever a time to listen to her, it’s now,” Chapman says. “The Shawnee are out for blood.”

“So am I,” the man says, and slams the door.

Chapman runs through the town shouting warnings, until candles flare in every window. The streets overflow with people carrying bags and provisions. Mothers drag children by their wrists. Everyone floods toward the fort, whose spiked walls stand in mute defiance. Men gather in groups amidst the chaos, guns dangling at their sides.

Panting, Chapman stops at a corner and leans with his hands on his knees. Disaster may yet be averted. Just as he catches his breath, he finds himself once again surrounded by a group of angry men.

“How do we know you’re telling the truth?”

“You been out there living with them Indians?”

“Hell, he’s probably trying to trick us in there, so the sons of bitches can come loot our homes. I say we stand and fight!”

“You’ll need a militia for this,” Chapman says. “There’s too many of them.”

“What are we supposed to do? Hide like cowards while they run wild through town?”

“There’s a garrison over at Mount Vernon,” someone says.

“It would never get here in time.”

The men make some quick calculations. There are fewer than two hundred men in the town, and a third of those are too old to fight. Suddenly, all at once, like a flock of birds changing direction, the men become frightened. “We’re about to get scalped, gentlemen.”

“How far is it to Mount Vernon?” Chapman asks.

“About twenty-six miles,” a man says. “South, through Fredericksburg.”

“Well, if Philipides can do it, so can I,” Chapman says. He grins at the men. “Of course, he dropped dead afterwards.”

“What in the hell are you talking about?”

“I’ll go rouse the garrison. They can make it back here by dawn.”

“None of us is loaning you a horse, you damn fool. Hell, you’d probably run right into the damn Shawnee and get chopped up.”

“No,” Chapman says. Already his calf muscles are twitching, his feet are moving. “I can see in the dark. Get your women and children into that fort,” he says, breaking through the circle of men. “And don’t do anything stupid.”

Soon he is out of the town, running down the dark road. His bare feet skim over briars and rocks. His mind detaches from his body and he imagines Swedenborg, sixty years ago, scribbling at a table by candlelight, somewhere in Europe, trying to capture the visions he had just received. He imagines himself, Swedenborg, and Abukcheech sitting down to dinner together. The road widens and he passes through sleepy Fredericksburg without waking anyone. When he reaches Mount Vernon, in the darkest pre-dawn hours, he starts shouting again, but his voice comes out a croak. He pounds on a door and someone opens, a dark figure, and Chapman hears himself babbling about Indians and garrisons and forts and help, but now his legs buckle. His lungs burn, his tongue swells in his mouth, and he falls to his knees at the doorstep. Boots clomp around him. Shouts, torches. The jingle of halter bells. A soft female hand touches his face, drips water into his mouth. His body trembles as with cold, though the morning is quite warm now. Something occurs to him: the soldiers whom he has roused will descend upon the Shawnee with the same vengeance the Shawnee had for those settlers. Violence for violence. Death for death. “Why,” he moans, as the woman pours water over his head. “Why?”

“Because you’re burning up, honey,” she says. “You need to rest.”

“Wars and rumors of wars,” he says, thinking of the Book of Revelation.

“That’s right,” the woman says. She pushes him gently back. “You’re all right. Just lie still now.”

Chapman rests his head on the dewy grass, and sleeps.

Chapman, in the woods, crouches down to scoop walnuts. Liver spots decorate his hands. His beard, almost completely white, hangs halfway down his chest. Blue eyes blaze from within a network of lines. He moves slowly, fills his satchel with nuts, makes his way back to the road. His wooden staff swirls dust before him.

He has no idea where he is.

At the edge of a town, a preacher stands on a hickory stump and addresses a crowd of several dozen men and women. Chapman approaches from the back, his bible clutched in one hand.

“My friends, you are on the path to evil. That’s right, every one of you. This great country of America had a chance to steer itself the right way. It had an opportunity to do something no other nation had ever done. It had the chance to turn toward Jesus. But it failed. It failed, friends, because all of you got caught up in material wealth. That’s right, you.” The preacher points at individuals in the crowd. “And you. And you.”

Chapman squints at the man. He’s young—no more than thirty—and dressed in a ratty jacket and patched trousers. He shakes a bible in the air, and Chapman marvels at how thick the book seems—much thicker than his copy. Then he remembers: most of his pages have been torn out.

The preacher goes into a mock falsetto voice. “How much land can we grab? How many clothes can we buy? Where do I get those fancy new boots? What about toys for the children? A new horse, a new cow, a new slave, a looking glass? Jewelry?” He raises both hands to the sky. “Friends, Jesus Christ himself told us that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God. The way you’re headed is the way to Hades, let me tell you. Where can I find a man who, like the early Christians, is traveling to heaven bare-footed?”

“You’re wearing shoes, yourself,” someone calls out. The crowd murmurs around him.

The preacher lowers his head for a moment, then looks up and speaks in a low voice. “I am a traveling minister, friends. I travel in the name of Christ. But you—you farmers and mill workers and shopkeepers and horse dealers—give up your wealth, give up your possessions! Come to God as he made you! I ask again: who among you is like the early believers? Who here is journeying to heaven clad only in what the Lord provides?”

“You want us to walk around naked?” someone calls. General laughter. The preacher reddens.

Chapman seizes this opportunity. He nudges his way through the crowd, to the hickory stump, and plants one bare foot upon it. His toes are black with grime, the toenails hardened and yellow. “Here I am,” he says. The audience howls.

“Why, sir,” the preacher stammers. “Sir, I—you—well—I do believe I stand corrected.” He gestures toward Chapman. “Only one man here today is living as he should. Let him be an example to you all.”

Chapman turns to the crowd. “Jesus doesn’t care what you wear. Just treat each other well. That’s all that matters.”

* * *

Chapman is confused. He can’t remember the last time he ate, but he doesn’t feel hungry. A sort of numbness has overtaken his body. He rambles through rocky fields—is this still Ohio? Is he going east or west? Low clouds make it impossible to tell.

High above, a vulture circles.

Chapman feels a presence beside him. Someone walking with him. He stops in the middle of the field and turns around and around. No people—only a distant orchard on a hill. He heads toward it, laboring slowly. Footsteps again fall beside him. His mind playing tricks. Unless—is it Nat? Is it one of the children he read to? Is it Abukcheech? Is it that woman, that farmer’s wife, who had eyes just like his?

It’s no one, he decides. It’s everyone. It’s God. He’s walking with God.

This orchard feels familiar. Chapman walks among the trees and touches their trunks, caresses each one. Whoever planted these did so expertly. Then he realizes: this orchard is his father’s, he’s back in Massachusetts somehow, and there’s Nancy Tannehill—white hair, blue eyes, old skin, sagging bosom. Walking now with a stoop. She clutches the hand of a small girl, her granddaughter, and as Chapman approaches, she smiles. “I knew you would come back,” she says.

“Have you stayed here all this time?” Chapman says.

Nancy nods. “Eight children will keep a woman at home.”

“What about your husband?”

“Kai can’t venture out much these days. He’s almost blind now. But you, Johnny—you still have those same eyes.”

Chapman blinks a few times.

The little girl runs after a squirrel. Her blonde pigtails whip around. Nancy places a hand on Chapman’s cheek. “Are you all alone, Johnny? Didn’t you ever find someone?”

“I found a lot of people,” Chapman says.

“You know,” she says, “solitary trees won’t bear fruit. Someone wise once told me that.”

“My reward is in heaven,” Chapman says.

A fog rolls through the orchard and seems to carry Nancy away with it. Her granddaughter remains, squealing as she scampers through the heavy-laden trees. A fat apple plunks down beside her—just a few more weeks and the season will be over, the fruit will rot, the harvest will be wasted. Chapman looks for a ladder, but there isn’t one. Weariness washes over him, and he finds an old tree to sit under. The little girl skips over his outstretched legs, laughing. A sweet sound—indeed, the sweetest sound he can imagine. He will rest for a little while, and then he’ll help her pick some apples—bring them back to her grandmother—maybe he could finally plant those saplings in the back yard. But first a nap—just a small doze—just enough to regain his energy—just a short break before he gets moving again….

Chapman closes his eyes.

Dear Sir:

I am writing to inquire about your orchard, and to remind you of the particulars of its upkeep. First of all, remember to prune during winter only. That way, when spring arrives, your trees will distribute their energy into fewer branches, thus making those branches bigger. You will reap much more fruit in this manner.

Remember also to keep the buds at least six inches apart. The more room your apples have to grow, the bigger they will be.

If you ever plant a nursery of your own, make sure to do it on a hill with good drainage. The root systems of apple trees are especially delicate and susceptible to water damage. Tie your saplings to stakes and weigh down the young branches with rocks to give the tree a handsome scaffold shape.

It would also behoove you to place your young orchard near a windbreak—a barn or wall, or better yet, a cluster of full-grown trees. This way, during storms, you will not lose too much of your crop.

I am heading northeast at the moment, but whenever I venture your way again, I shall stop by to examine the orchard and offer any new advice. However, I am fully confident that you will be able to raise fruitful trees that will provide for your family, and even your town, for years to come. Apple trees will keep producing fruit for decades, if you take proper care, so even your grandchildren will be able to enjoy them.

Give my regards to your wife, and know that I think of your family often, when I am on my solitary rambles, and look forward to the day when I can sit at your table again. Until then, I remain,

Your friend,

John Chapman

N. T. Brown lives, writes, and teaches in Orlando, FL. His work has appeared in Matchbook, Nanofiction, Gulf Coast, Pebble Lake Review, and elsewhere. He has a dog named Seven and a cat named Mrs. Mia Wallace.

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?

In most historical fiction, there is a sense of dramatic irony---the audience knows things that the characters don't. We love Napoleon's cameos in War and Peace and Baron in the Trees because we know precisely what will happen to him, and his army, someday. We enjoy Russell Banks's Cloudsplitter because we all know what John Brown's ultimate fate will be. Even the movie Titanic falls into this category---we all know the boat will sink, though the characters don't. I think readers enjoy knowing what will happen to certain characters, and watching those characters advance inevitably toward their fates.

2 comments:

Powerful story -- a little darkness, a little light. It feels true. Encore!

I enjoyed how it took so many different directions almost as much as I enjoyed reading about such a pure man. If only more of us would feel as Chapman.

Post a Comment