Four Sacrifices

by Jonathan Edelstein

Crete, 1745 BC

Four things were together on the slopes of Mount Juktas: the temple, the priestess, the victim, and as always at temples, the gods.

The temple, built of stone, had three rooms and an antechamber. From the western sanctuary, where the priestess and the victim were, it was possible to look through the antechamber doorway, down to the palace of Knossos and the city beyond. The palace looked imposing even from this distance - more so, in fact, than it did from within, where many rooms had collapsed and walls crumbled from the earth-tremors.

In the sanctuary, opposite the sacred fire, was a block of white stone with figures carved around the edge, faded and stained from centuries of use. A trough was carved in the ground at its base, leading out to the antechamber and the hillside beyond. And atop it lay the victim.

He was eighteen years old, a young man in the prime of health, with black curls that gleamed in the firelight and brown eyes that held secrets. His wrists and ankles were trussed together, much as a bull-calf’s might be, and he had been placed so that he lay on his side.

He was not there willingly. There had been no volunteers for this ritual; there were many among the people, and even among the priests, who didn’t believe the necessity was dire enough. He might be an outlaw sentenced for some crime, someone who had aroused the wrath of his headman or guildmaster, a stranger who’d been in the wrong place at the wrong time - none of that mattered anymore, here in the place of the gods.

Certainly none of that mattered to the priestess. Had she not been taught that the gods must have what they demanded? Had she not shared the flesh of a child with her fellow initiates, long ago in this very temple, to teach her how unyielding the gods’ demands could be?

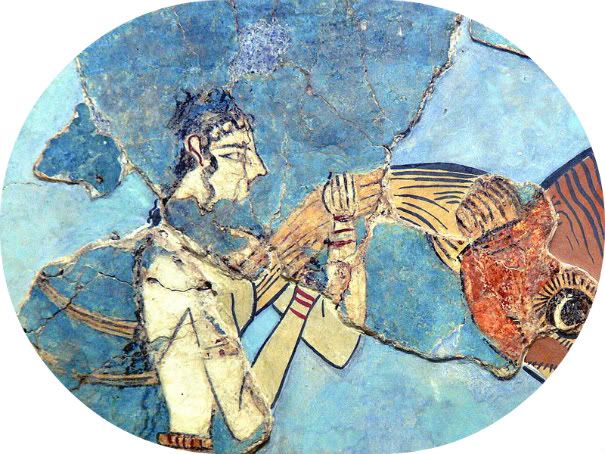

She raised her bronze knife over her head, letting the fire catch the lines of the boar’s-head etched in its blade. She pointed it at the city in the distance, at the sacred fire, at the wall-painting behind her which showed mountains, palace and sea. She chanted the ancient prayers, her under-priest joining the song as he poured libations around the altar. The victim said nothing.

He was a stranger, a potter from the south who’d come across the mountains with wares to sell. He’d come the year before and the year before that, and his work had been prized, but he was a stranger nonetheless. “Take him,” the villagers had said when the priests came, and the priests had done so. That had been three hours ago.

How beautiful it all is, he thought, and wondered at the notion. Shouldn’t his mind be fixed on his coming death, on his home, on the wife and infant son he’d left there? But it was beauty that filled him - the breathtaking view from the mountainside, the vivid colors of the wall-paintings, the marvelous tinted pottery made with love akin to his own, the shifting flames and the shadows they cast on the wall. Even the priestess, whose full form and open-breasted bodice might at other times have awakened desire.

Beautiful, even, was the bronze knife she held, which slipped between his ribs as if they were wet clay.

The sacrifice was completed. The priestess continued her chant, imploring the gods to speak.

They did.

The tremor was a hundred times as strong as the foreshocks which had shaken the land for the past month. The temple-ceiling shivered and gave way, raining blocks of stone on those within. The under-priest fell backward, raising his hands to shield his face, but his limbs were not proof against the heavy slab that fell on them. The priestess had not even that much warning; the block that fell on her was largest of all, sending her sprawling forward even as it crushed her spine.

Outside, a temple servant - the sole survivor - ran screaming to the palace to bear witness.

A long hour’s march away, another four things met their fate: the bull, the father, the mother and the child.

No priest was the father, although he had holy things in his charge. He kept the sacred bulls, the calves destined for sacrifice and the mature beasts that sired them. He fed them, groomed them, called them by name as he tended their needs. They were the animals whose shit he shoveled and who he doctored when they were sick; they were also his gods, and attending to them was an act of worship.

He was not educated as the priestess had been; he hadn’t been taught of the gods’ demands and caprices. The gods themselves would have to teach him.

The tremor knocked him off his feet, but it did more than that. It shook the paddock-fence and tumbled the rails to the ground. And it maddened the bull inside - the oldest and holiest of the sacred bulls, jet black in color and thirty talents in weight.

The father was just starting to rise when the maddened beast caught him in full charge. He went down under the hooves, his skull crushed, dead before he had a chance to cry out. He lay there, killed by his own god, and the god charged on.

The mother saw. She had come with their child to bring him his meal. She had managed to keep from falling, and watched as the bull trampled her husband into the earth. She had cried out where he had not, but her scream went unheard. And now she, too, was in the bull’s path, as was her daughter.

For a moment she stood frozen, watching without comprehension as the crazed bull bore down on her. Almost, she allowed herself to be charged down as her husband had been. Only at the last second did enough of her senses return for her to throw her child from the bull’s path.

But there was no time now to save herself. She stood before the charging bull, fully aware of the doom that awaited and realizing there was no possible way to escape.

Instead, she did the impossible.

Something within her - inspiration? desperation? embrace of death? the voice of the gods? - took control of her limbs. She leaped, not away from the bull, but toward it, and seized it by the horns.

The bull reacted with the instinct of its kind, throwing its head back to shake off the pest that had taken hold of it. The mother, her grip uncertain, lost hold of the horns and flew high into the air. She tumbled end-over-end three times and landed full on the beast’s back. Dimly, she realized she was astride it, riding it as she might ride a donkey.

She reached forward, caressing the bull’s neck and head, trying to gentle it as she’d seen her husband do. Something about the touch brought the bull back to itself, drained its madness away, let it fade to harmlessness as the tremor had by now done. Slowly it came to a stop, pawed the ground once with bloody hooves, and stood there as if nothing had happened.

By now, others had come, and they had seen. They took charge of mother and child, and helped lead the bull back to the paddock. And they, too, bore witness.

Four things now assembled for the sacred trial: the minos, the priests, the witnesses and the gathering.

The first three were always present in a trial of the gods; the last never. Such hearings took place in secret chambers deep within the palace, where the priests read portents and consulted oracles: only afterward, and sometimes long after, were their verdicts delivered to the people. But now the secret rooms were in ruins, and the portents that must be judged were like none before: the palace had been brought down, a sacred bull had killed his keeper, a temple had been destroyed during the very act of sacrifice.

Lesser signs than this had caused kings to fall and nations to be overthrown. The people had clamored for the trial to be held in public, on the very field where the bull-keeper had fallen, and not even the king had dared oppose them. So the minos and the high priests on the dais faced the people in their thousands, the villagers gathered in their tribes and the townsmen in their guilds, and wondered, for the first time they could remember, whether their verdict would be accepted at all.

The temple-servant and the mother had given their testimony already, and now the next witness, the holy examiner, took oath. She was a wizened crone of eighty, a distant relative of the minos and a member of the most secret of the priestly orders; her body was shrouded in a shapeless black cloak, and a silver charm in the shape of a snake wound around each arm.

The king addressed her. “Divine one” - she had given up her name when she joined the snake-priesthood - “give now your report.”

“I went to the Anemospilia temple with a dozen workmen, and pried away the stones that had fallen during the great tremor. We found the priestess and the under-priest buried under them, with the victim of their sacrifice still on the altar.”

“Are you certain,” the king said, “that the sacrifice had already been made?”

“The knife was red with his blood, and the altar around him was stained. Half his bones were black where the sacred fire had charred them, and half were white. He was only half bled out when the tremor happened; he must have been sacrificed only moments before.”

A moan went through the gathering as the import of this testimony sank in. The gods really had rejected the sacrifice, destroying not only the priestess who had performed it but the temple where it had taken place. What mighty curse would fall on their nation now?

“Who was the victim?” asked one of the high priests on the dais.

“A trader from the south. He’d been there to trade before, but none of the villagers would admit to knowing his name.”

“A stranger-sacrifice?” the priest cried. “Little wonder the gods rejected it! Who are we, that we give strangers to the gods rather than sacrificing something precious to us?” A rumble of agreement, low and dangerous, ran through the assembly.

“How may we atone, then?” said the king.

“We must give our own children to the gods. Many of them, to atone for such a terrible sacrilege, and they must be the finest we have to offer. The children of the nobles, even,” the priest’s voice flattened, “the children of the minos.”

The king’s face turned white. The high priests were no friend of the throne, or of the royal council that was increasingly dominated by the guildmasters and merchant princes rather than the priesthood, and now they had a chance to end the dynasty. If the people believed that the gods wanted his children as blood-sacrifices, they would demand precisely that. But was this priest speaking with the voice of the gods, or with the voice of a man who saw an opportunity to seize power?

“Is that the verdict of the gods?” he asked, trying to hide the tremble in his voice.

“It is…” began the other priests.

“It is not,” said the holy examiner.

The priests on the dais fell silent, much as they would have liked to do otherwise. They hoped to use the mob, but they were at its mercy as much as the king was, and if they denied a snake-priestess her say, the gathering would tear them apart.

“You are looking only at one thing,” the snake-priest continued. “We must look not only at the sacrifice the gods rejected, but the one they accepted.”

“The bull-keeper?” a high priest began. “That was no…”

“Not the bull-keeper,” the examiner said. “The mother.”

“That was also…”

“No sacrifice? Quite the opposite. She cast her child aside and took the gods’ wrath upon herself, and she stood before the god to accept his penalty. And the god spared her.”

Another murmur ran through the assembly. Many of them had seen what happened at this field on the day of the earthquake, and all of them had heard; they knew that something holy had taken place, but until now, they’d lacked an explanation.

“The gods want no blood-sacrifices of men or women,” the snake-priestess said. “They made that plain a month ago when they brought down the temple of Anemospilia. They want us to offer ourselves to the bulls, and they will take us if they deem that punishment is necessary.”

“Who would do that?” the high priest asked. “Who would stand before a charging bull and accept its wrath? If that is what the gods want, who will give it to them?”

For a long moment, the assembly was silent, and the priest’s challenge stood unanswered. Who would dare to submit themselves to the bulls now, when aftershocks still rocked the city? Then the mother stepped forward - the mother who had lost her husband and saved her child, and who had survived the wrath of a god.

“I gave myself to the bull once,” she said. “I will do it again, if that is what the gods demand.”

The roar from the assembly said that, whether or not the gods demanded this act, they did.

* * *

And at the solstice, four things combined to make the sacrifice: the bull, the mother, the minos and the field.

The field was the one where the mother had dared the bull before, and where the holy trial had been held. The sacred field, the people called it now.

The bull entered the field rampant, magnificent in its freedom. The mother stood at the opposite end, waiting for its charge. She was nineteen years old, young and strong, and had practiced for this day, but she was still uncertain: would she be able to do in cold blood what she had once done in despair? Could she withstand the bull’s charge long enough to give herself to it, and grasp its horns?

She could.

The bull ran toward her, and she stood her ground. She would not give in to her husband’s killer, and he would not risk renewing the gods’ anger now that the earth was calm again. The bull was fifty feet away, thirty, ten, and still she stood firm.

At five feet, she leaped off the ground and caught the bull’s horns, letting it throw her into the air, letting her momentum shape her flight. And this time she landed standing, riding the back of the bull for a split second, throwing her arms high in triumph before gathering herself and leaping off.

The mother let herself be gathered in by her fellow bull-priests, the young ones she was training to take her place, while the people at the boundaries of the field cheered in release. She noticed not as a bull-calf was brought in, borne on a silver shield by four priests, and brought to the bonfire where the minos stood. The king raised high his two-bladed labrys, showing it to the gods, and brought it down on the calf’s head.

The sacrifice was accepted.

Jonathan Edelstein is 40, married with cat, and living in New York City. His interest in the Neolithic and Bronze Age worlds has taken him to Newgrange, Teotihuacan, Crete (including the temple that is the scene of this story) and other places.

This is his first fiction publication. He is working on the second draft of a Minoan novel set about a century after the events of this story.

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

It's important to be open to all the worlds of the past on their own terms, and never to underestimate them. The past is a country in which people thought, loved, feared and questioned as we do today. We know a few more tricks than they did, but we aren't a bit smarter or more human, and a story shouldn't sell the past short by treating its people and societies as caricatures.

0 comments:

Post a Comment