Rob In the Hood

Translated by G. K. Werner

Translator's Note: If ballads were sung concerning Robin Hood's father (and they ought to have been), they were never recorded, or fell to parchment’s foes: moisture, moth and flame. For the elder Robert Hood’s deeds, posterity is entirely dependent on the Clerk of Copmanhurst whose historical veracity Sir Clee Pearson’s scholarship has firmly established.(1)

–GKW, Seaford, 2011

From the Clerk of Copmanhurst's(2) first letter: Robin Hood was the son of Robert Hood, and many a ballad the elder Robert’s deeds would have made had not the younger become so famous, (Or should we say infamous?), for Robert defied the Normans long before Robin set arrow to string. Study the parents to study the man, as the Gaffer used to say, thus it began…

The Tale:

Wakefield, Yorkshire, England, 1136

The Hoods of Wakefield were a fiercely independent lot, Saxons(3) who leased small holdings, feared God, and stood loyal to the King; but cared not a snap for the wealthy barons, bishops and sheriffs who lorded it over them, and had for more than two generations at the opening of our tale, ever since the invasion led by Duke William of Normandy, and the Saxon defeat at Hastings.

William had carved England for his Norman barons to feast on; warlords, who squabbled ceaselessly among themselves, raised cold stone towers and clenched England in mailed fists. They claimed the vast forests as their own, ruthlessly enforcing their harsh game laws, even in lean years. On every manor and great estate, in every village and town, law was defined by a Norman's will and imposed at the point of a Norman sword. Justice was weighed out on a Norman scale, and Saxon life and livelihood hung in the balance. The church hierarchy, the bishops and abbots who should have offered sustenance to the poor, support to the down trodden, and sanctuary to the falsely accused, had been replaced by Norman bishops and Norman abbots as corrupt and overbearing as any baron or sheriff. Even after King Henry married Eadgyth, a descendent of the great Saxon King Alfred, and marriages between Norman and Saxon houses increased, strife between Norman and Saxon remained as strife between rich and poor, the powerful and the powerless.

When Robin’s father, Robert Hood, was born on a cold winter's night in 1136, Stephen kinged it over England, ruling with a lax hand, doting on favorites, allowing them broad liberties and immunity from justice in return for support in his endless struggle against Empress Maud, daughter of old King Henry who, she claimed, had promised the kingdom to her son, also named Henry. Robert's mother died in childbirth as the snow deepened outside their one-room tenant-cottage, lovingly held in her husband's arms, cradling their first-born in hers.

And Stephen was still king, and matters worse, his reign dubbed ‘the Anarchy’ ten years later when Robert's father died on a Norman sword. Wakefield’s Father Wilibald offered to take the lad in and raise him in the church—much to the relief of Robert’s relatives, taxed into the soil they tilled to finance Stephen's wars or the rebellions against him. Barely able to feed their own children, they were in no hurry to take on another boy's appetite.

All Hallows 1146

All Hallows, the parish church, stood in Wakefield’s center where the town’s main streets met atop a hill overlooking Calder River. The Anglo-Saxon church had been rebuilt in the Norman style, its chancel, nave and transepts forming a simple cross with a central tower supported by plain round arches; but, miraculously, a Saxon priest still served the local flock.

Robert moved into the one-room, lean-to house against the church's back wall where Father Wilibald lived alone.

"Welcome, lad! Welcome! Thrice welcome! And more! My home is yours now lad, long as you want it, and right glad am I of the company, I don't mind telling you. A humble home, but all we need, praise the Lord for his bountiful blessings. Cozy and dry, a patch of fertile soil at our door, a goat for milk, a fire for warmth and cooking. Look! A chimney! More than most folk have. Built by the church builders. Runs straight up the church's back wall, our back wall that is, so there is no fear of fire and no smoke to sting our eyes as with ordinary hearths."

Wakefield's wiry little priest chattered like a squirrel nimbly darting to and fro amidst the clutter of scrolls and writing implements, gardening tools and stock, dishes, pots and utensils; his halo of wispy white hair floating along in the breeze of his passing. He cleared a space for Robert's sleeping matt in a corner against the church's wall, piled fagots in the fireplace and struck kindling ablaze with flint and stone, then set to work on their evening meal.

His spoon rattled round and round the big stew pot hanging in the fireplace as his tongue rattled round his mouth. “Hungry, lad?” He tossed in more cabbage and onions, sprinkled the mix with various herbs he had gathered and dried, naming each one in turn. "Enough to feed the king's army. Or the Queen’s! Praps even a ten year old boy's stomach."

Ironically, Robert refused to eat. He also refused to speak and, worst of all, refused to cry.

"He needs a good cry," Wilibald told his goat next morning during milking. "That is what he needs. Then we can talk it out. And then he will eat."

The goat bleated dismally.

"Oh me. I fear he will die of starvation without ever shedding a tear. Poor lad."

The goat agreed.

"What am I to do?"

The goat had no answer.

Wilibald stopped milking and prayed to his Lord, begging for an answer. Then he listened for one.

Wait.

He waited while visiting Widow Crum and her three baby lads having brought her one of his renowned mercy-meals. He waited while tending the sick in town, while sweeping out the church, and while cooking supper once more in his lean-to house round back. He waited through evening mass, and all through confessions.

No answer! "What shall I do, Lord?" Nothing to do! It was all in the Lord's hands.

After the service, Wilibald found Robert hiding in a musty closet. “Come along lad.”

No response.

“Come along now Rob. You can not live in there.”

Robert snatched a brown hood off one of the pegs and buried his head in its deep folds. He slumped out of the closet, eyes covered, nose and chin shadowed.

"Hie, lad. You look a right proper monk in my old hood. But how will you know where you are going?"

Robert refused to take it off. He slept in it that night, and kept to himself the next day, huddled in his sorrow at the foot of the preaching cross in the street in front of the church, arms folded and chin on chest, sunk out of reach in his hood. At dusk, Wilibald found him in the graveyard on his knees before his parents’ little stone cross. His sunken cheeks and wan, famished complexion within the hood came near to bursting old Wilibald's heart.

“Supper is on the fire, lad.”

No reaction.

"Your milk is his only nourishment," he told his goat that evening. "Three nights now. He will die if he keeps on like this. He will die and not a thing to do about it.” He fell to his knees. “Oh what shall I do, Lord?"

Wait!

On the third morning, Father Wilibald delivered a mercy-meal to a farmer's ailing wife. He returned to an empty church and an empty house. He called to Robert over and over with increasing urgency, searched every closet, beneath every pew, in every nook and cranny from belfry to root cellar. Robert was nowhere to be found.

Wilibald ran up Northgate and out Warrengate and Westgate ways, down Kirkgate and over the old wooden bridge and back again, a shepherd who had lost his lamb. "Have you seen Rob?" he asked everywhere. "Have you seen the lad?"

The tanners hadn't. Nor had the dyers.

"I saw 'im on the church steps at dawn," the milkman said. "But not since."

Robert had not been down the lane to watch the thatcher knitting his roofs, or out to watch the stone mason building his new ‘dry wall’ with fieldstones,(4) or to visit the wright with his saws and hammers. He used to sit for hours watching these men in the days before his father’s death. But neither thatcher nor mason nor wright had seen him. "Not in days, Father." Neither had the smith (another favorite), nor the potter (sudden thought), nor the spinners(5) (who always knew where everybody was and what they were doing and with whom).

"He'll(6) turn up," the big red-faced pindar told Wilibald, clapped him on the back and offered a pull at his wine-skin. "Strays mostly do. And I should know. They wander back when least expected. When they're 'ungry enow." He counted on it, being a lazy pindar.

Wilibald scratched his wispy-haired scalp, less certain. His little stray had shown no evidence of an appetite.

The women at the communal ovens were the most concerned. They spread out like hens after a lost chick.

Trembling in exhaustion and near panic, Father Wilibald sat down to pray.

* * *

It was Widow Crum who brought him news late that afternoon. "Master Sklar saw your lad,” she said, breathlessly, “entering Barnsdale.” So folk named the great forest that extended from Wakefield south to Sheffield and east to beyond the Great North Road.

Wilibald sprang to his feet. “Barnsdale?” he cried. Elves and ghosts were said to haunt forest depths, and dragons—folktales superstitious villeins(7), socmen(8) and burghers(9) spread—lies forest owners encouraged. But danger enough of a natural sort awaited a boy of ten, lost in the Great Wood’s depths—not least of which, outlaws. “And did our bold forester go in after him?" he asked the Widow.

“Says ‘e lost 'im.”

“Lost him? A ten-year-old boy? Master Sklar? The king's forester?” The king had appointed forest wardens who in turn appointed foresters to patrol the local woodlands. Sklar was theirs! Most wardens never saw their forest and most foresters never entered theirs. Sklar, for one, was too busy—forever poking into Wilibald’s mercy meals, nosing about trying to discover just how it was a poor priest never ran short of meat for the poor. “Did Master Sklar at least have the wits about him to remember where?”

"Oh aye. Past the meadow. Down by the bee skeps."

At twilight he found Robert sitting on a stump in Barnsdale Forest. The hood hid Robert’s eyes, but not the tears streaming down his cheeks.

At last! Praise the Lord!

Wilibald sat down beside him and put an arm round his shoulder. "That's it,” he said. “Have a good cry, lad. Grief is God's gift to us when we loose our dearest. A tangled forest beyond which lie meadows and brooks of ever brightening day."

"Why?" croaked little Robert. "Why?"

"Your da was a man of principle, a man after God's own heart. What he did, he did without thinking. Without considering the danger! He did not want to leave you. But your da was not a man to stand by and watch another man beaten and a woman…harmed. Even though they be strangers to him."

"He killed my da!" cried Robert. "The squire killed him. And then…then his men killed the man anyway, and his wife…they…his wife…"

"I know." Sights a ten year old boy had no business witnessing. Who did? Sights all too common these days. Knights turned cutpurses and rapists! And now their squires as well? A boy not much older than Robert, by all accounts! Wilibald gathered the lad in and rocked him while he shuddered, sobbing his grief into the old priest's homespun habit. "She is with the Lord now. So is the man. So is your da! He is with your mum. At peace! Beyond the reach of those who can only harm the body but never the soul. Never the soul! That belongs to our Savior."

"But why?"

Wilibald shook his head, tears streaming down his own cheeks now, mixing with Robert's. "I do not know, lad. I do not pretend to know. But we will know one day. All of us will. When we are with our Lord in paradise. And He will wipe away our every tear."

They sat in silence as night deepened and the forest, hushed by their presence, seemed to draw close and embrace them.

“One day,” Robert whispered in the darkness, “I will kill the squire.”

A chill gripped Wilibald’s spine.

That night, Robert broke his fast on buttered scones and warmed broth. In the morning, after Robert’s third helping of porridge, Father Wilibald set the boy to work. "Busy hands banish gloom," he said. Robert's chores included sweeping out the church and replacing the rushes, white-washing the stoop, fetching firewood and water, and polishing the silver candle sticks that were the church's only valuable possession other than the large hand-copied Bible beyond monetary value. And right gladly did Robert perform such tasks, with a good heart, assisting Wilibald in tending the sick and crippled and serving as altar boy during mass.

No more was said or heard of vengeance, in the days and weeks that followed. Wilibald committed the matter to God, who alone changes hearts.

Books being rare,(10) the big Holy Bible chained to the alter fascinated Robert, its hand-lettered pages ‘illuminated’ by colorful marginal decorations and elaborate initial letters—the work of a talented monk-craftsman. Father Wilibald rose each day before the sun to study Scripture by candlelight in the sanctuary.

One morning, silent as a fox, Robert crept after him and watched, wide-eyed. Deciphering symbolic marks on a page was a magical act to most folk of that day. Wilibald’s thin, bristled lips buzzed like bee wings as he sat on his stool reading God's Word.

Reverently, Wilibald closed the Bible and, as Robert stepped from the shadows, almost jumped out of his habit.

Robert laughed.

The old priest melodramatically put a hand to his chest.

Robert’s laughter echoed in the church’s stillness. Another prayer answered, Wilibald noted. Laughter – the Lord’s gift.

Robert gently touched the ornately engraved leather-bound cover. His finger traced the intersecting lines and embossed Celtic cross.

Wilibald smiled. “Have you ever seen a book before?”

Robert shook his head.

“Most books have pages protected between wooden boards. Did you know that? Wealthy churches have Bibles with cover-boards encased in beaten gold or silver, some encrusted with precious stones and closed with metal clasps and locks. Can you imagine? I saw such a one in York. But our humble copy is quite beautiful enough with its enamel cross, don't you think? And sturdy. See? Each page hand-sewn with linen thread to flexible leather hinges. The gospel's simple message is its wealth and beauty.”

Robert frowned suddenly. “Does God really say we must forgive our enemies?”

“That He does, Rob. As He has forgiven us in Jesus.”

Robert pondered this. “What if we can’t?”

“With God, all things are possible.”

Robert’s frown deepened. “What if we don’t want to?”

Wilibald put a hand on the alter to steady himself. “Would you like to learn how to read?”

Robert’s face brightened.

“I’ll teach you, if you like. Then you can read Holy Writ for yourself.”

Robert opened the book. His wonder-lit eyes searched the page.

He took to reading like a buck to forest leaping.

Month in and month out, he listened as Father Wilibald read over his shoulder, his gnarled index finger underlining the words. Robert loved Mary’s story. He wanted to hear it over and over till his own finger traced the words unassisted—Virgin Mary, visited by an angel. Graceful Mary, who trusted God and gave birth to His Son. Sadly, Holy Writ did not include Mary’s physical description, but Robert pictured her medium tall and plumpish, with hair like wheat warmed in the sun, cinnamon colored lips tenderly shaping a lullaby—the mother he'd never known, as described by those who had.

By the end of the year, he could read stories unassisted—Elijah confounding the priests of Baal, Joshua conquering a city, David felling a giant—all by the grace and power of God.

And if a boy like David could fell a giant—

Calder River, 1147

“Cept you’re no David,” said Niles Nettles, the innkeeper’s gangly son. Robert’s sudden dark moods always disturbed him. Niles skipped a stone across the pool River Calder formed beneath the bridge. It missed the wooden piling for which he had aimed.

“And the squire is no giant,” said Robert. “Only a boy! No more than five years older than me and slim as a sapling.”

“With a broad sword! And being trained to use it!”

“I’ll learn how to use a sling,” said Robert, skipping a stone smack into the piling. He rarely missed.

“You don’t even know his name or his liege lord’s.” The only other witnesses, Old Gil the fisherman and Sklar the forester, had not recognized the squire’s livery or its device—a red flame on a black, circular field. Neither had anyone else when the folkmoot met.

“Just keep your eyes peeled.”

“Robby, he’ll not come knockin’ at me father’s door. Not close on the very place where he…er.”

“And your ears open,” said Robert, trying to block the horror from his mind—his father’s blood, the woman’s screams. The Blue Boar on the highway just south of the bridge was a popular inn. The burgeoning wool trade brought numerous merchants, prelates, knights and barons through Wakefield. Surely Niles would one day overhear news identifying the squire.

Niles stared into the pool shaking his head, but Robert knew his best friend would help.

“An’ what if he does come?” said Niles. “You’ll not have justice from Norman lords. And a stone won’t slay an armored Norman.”

“All things are possible,” said Robert, “with determination.”

Barnsdale Forrest, 1148

Robert loved the greenwood—Outwood to the north, Thorne Wood to the west, and especially Barnsdale which Wakefield folk called the Great Wood. As his stride lengthened, he roamed its outskirts east and south of Wakefield every chance he got. Father Wilibald told him Barnsdale got its name from Beorn’s Dale in the Skell Stream’s valley south of Wentbridge, a place where Vikings once lived. He was filled with forest lore.

Robert found a glade where daisies opened to hard-working bees and an owl slept in a yew tree by day, where strawberries were the sweetest, and (if he kept still enough), the fallow deer came to eat the bark of linden and birch; a place where he could contemplate God's creation and the things he learned from Holy Writ under Father Wilibald's tutelage. A place, Niles would be surprised to learn, where Robert also spent time in prayer begging the Lord to free him of his lust for vengeance.

On the morning of Robert’s twelfth birthday, Father Wilibald found him in his secret glade. Though a slight man, Wilibald shattered its tranquility, crashing through bracken, startling birds and deer into flight. “How did you find me?”

“Sorry, Rob. Everyone needs a quiet retreat. I won’t reveal yours to a soul.”

Robert suddenly realized he had not heard Wilibald’s approach, only his arrival. “Did you track me like a huntsman?” Father Wilibald must be more at home in the forest than he let on.

“I could not wait till later.” Father Wilibald had something in his hand. A quarterstaff?

“Wait for what?” asked Robert. “What is that?”

“A gift for you,” Father Wilibald announced in his pulpit voice.

Robert laughed in delight. “But what is it, Father?”

“Like me, it is ancient.”

“And skinny!” said Robert, and laughed even louder.

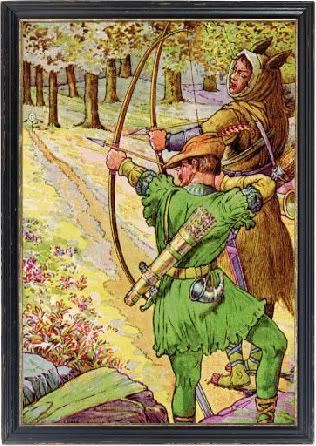

Wilibald laughed too now. “But strong still. And limber. He presented his gift. “This is a longbow.(11) Its making a secret guarded by grim Welshmen.”

Robert eagerly accepted the gift. His hand traced the longbow’s smooth surface. He had never seen its like. The shorter English war-bows and still shorter hunting bows seemed childish in comparison. “A longbow,” he repeated.

“Best there is. Made by my old friend Elwyn the Welshman(12). Served me well, it has. I was a King's Bowman before I was a priest you know.”

Robert had not—his eyes wide.

"But that was a long time ago. In old Henry’s time! A very long time ago! We shall see if I can still bend it proper. I have a new string in my pouch here, twisted from hemp. I have been working it with water glue at night while you slept.” Robert watched Wilibald loop the string into the bow’s bottom notch, brace it against his right foot and, with a bunching of wiry muscles Robert never dreamed the old man owned, deftly bend the bow, slipping the string's second loop into its top notch. "Now then. What shall we use for a target, aye?"

"You need an arrow," laughed Robert.

"Ah! So I do. Here's one." From the back of his belt he produced a shaft neatly trimmed with grey goose feathers. "Now then," he said.

"Hit that knot in the log over there," said Robert, pointing to the glade’s far end.

Wilibald squinted into the distance. "I scarce see the log," he said. Then he shrugged, and in one smooth motion nocked, drew and released his arrow.

Robert clapped his hands and ran to see. Old Wilibald's arrow had lodged a finger's width outside the knot. “What a clever shot!” Robert thought he had named the impossible.

Wilibald shook his head and clicked his tongue. “I shall have to do better than that if I am to set a proper example for you.”

Robert caught his arm. “So this is why your mercy-meals never run short of meat!”

“Clever lad!”

Robert’s face became grave. “But it’s death or worse to steal the king’s venison.”

“Better to break the king’s law than God’s will,” said Wilibald. “I simply spend the talent He gave me.”

“May I try it? May I? Now?”

Wilibald showed him how to hold the longbow at an angle, it being longer than a boy. “Always remember, Rob, a longbow takes life or gives it. The bowman decides.”

V

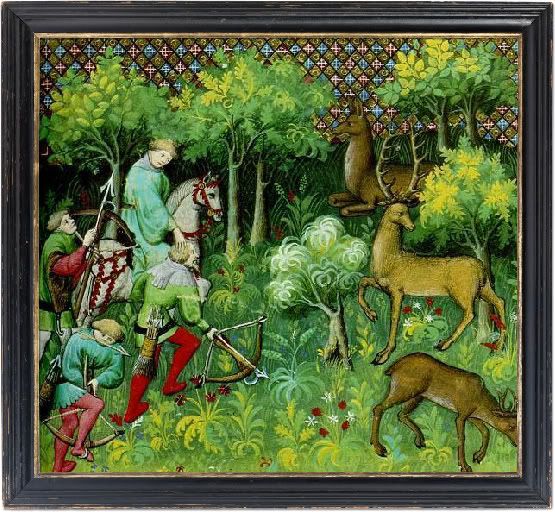

Heath Common, 1151

Merry Wakefield(13) was never merrier than on May Days. Celebrations always included a shooting match held on Heath Common, southeast of the village. When Robert Hood turned fifteen, old enough to compete in the competition, he revealed his longbow for the first time.

It impressed his friends. “But can you use it?” they asked.

His first arrow struck the mark, qualifying him for the main competition. Wilibald smiled proudly.

“How did you spare time to learn a trick like that?” asked Niles Nettles, knowing how busy the church builders kept his friend.

Robert’s fascination with building trades had become his occupation a year earlier when the new Warrene lord(14) began a building program at Sandal Castle and All Hallows. A north aisle for processionals was being added to the church, seven bays of alternate octagonal and round columns. Robert worked hard as both apprentice wright and rough mason, but never neglected his lessons in Scripture or bowmanship. He practiced secretly in Barnsdale, fashioning garlands and setting up willow wands as targets, far from meddling elders and taunting peers. His skill had surpassed a royal forester’s within months and old Wilibald’s by year’s end—which was when he insisted his bowmanship alone would supply the priest’s mercy-meals.

They won’t catch me, Father, he had said.

Meaning they will catch me, Wilibald had replied.

Sooner or later, Robert’s look read. You gave it me. You can not be borrowing it back all the time.

Very well then, Rob! I admit I am not as spry as once I was. But, if I permit this, I want your promise in return—that you will never put your bowmanship to the purposes of war. Promise! Robert had promised. He would confine himself to feeding the poor. He could get back at the Normans and do God’s will at the same time. Was that what Wilibald had intended by giving him the bow?

Now, two years later, when the crier announced the finalists in Wakefield’s May Day shooting match, Robert’s name was among them. His friends were amazed. “All things are possible, Niles, with determination.”

Niles rolled his eyes.

“And where would a Saxon find a bow such as this?” demanded an imperious voice at Robert’s back.

Robert turned to meet the haughty gaze of a young knight in chain mail, whose jet-black surcoat was emblazoned with a red flame. The hooked nose and close-set eyes made the lean warrior into a bird of prey. Even though five years had passed, Robert instantly recognized him. The squire who killed his father had become a knight!

And where did a murderous cur find the spurs of a knight? Robert wanted to ask, but held his tongue.

Father Wilibald put a hand on Robert's elbow—a warning? Or the grip of an old ex-warrior prepared to block his foster son’s rash act?

“Speak, bowman,” barked the squire at the knight’s side. “Sir Isambart de Belame, lord of Bleakstone Castle, and Baron of the Fells addresses you.”(15)

Belame! He had the name at last. Isambart de Belame—with a squire of his own now. Robert spoke evenly. “My bow was a gift, milord.”

“From whom?”

Robert did not answer.

“The gift of a rebellious Welshman, no doubt,” said Belame.

“I see you know your bows, milord,” said Wilibald(16). “And have a right fine war-bow strapped to your charger’s saddle. Would you care to test it against a longbow? I am certain the provost of the games would grant late entry to a knight of the realm.”

“I would prefer to test this Welsh bow against the mark,” said Belame, reaching a slender hand for it.

“I would be no true bowman to hand it over for the asking,” said Robert.

“How dare you, boy,” cried the squire, half drawing his sword.

“Be still,” said Belame. “We have not come here to shed Saxon blood. Fetch my bow. I will join the finalists in their shooting.”

Robert’s thoughts whirled. At this range, his bow could put an arrow straight through the fiend, chain mail and all. That was his first thought. His second was to publicly accuse Belame, denounce him as a murderer and a false knight. But of the other two witnesses, one was now dead and the other a Norman puppet—Sklar the Forester (who suspected him of poaching in Barnsdale but could never prove it, followed him but could never catch him) would certainly perjure himself for Norman coin.

Belame sneered. “We shall see if a fancy bow shoots straight in Saxon hands.”

Robert prayed for a steady arm and a keen eye. Perhaps victory at the butts(17) would heal his riven heart.

Five bowmen stepped up in turn to shoot. Five arrows struck the target. Two stood in the pin(18) —Belame’s and Robert’s.

The crowd cheered, and Niles and Robert’s friends shouted Hood! Hood! A-Hood! above the din.

“I see you are adding a north aisle to your church,” said Belame to Wilibald while selecting another arrow from his store. “Would you care to balance it with a south aisle?”

“That would necessitate violating the grave yard,” said Wilibald.

Belame shrugged. “Will the dead care?”

Wilibald regarded the youth in astonishment.

Belame returned his stare. “I am offering the Church a gift, priest. A substantial one!”

“Why?” asked Wilibald.

“Why?” said Belame, fitting his arrow to his string. “To sanctify my newly won knighthood, of course, and the honour(19) I have inherited.”

Wilibald studied the young man.

Belame studied his arrow’s point. “I have come into my own and would cleanse myself of certain…excesses. So to speak.” He cleared his throat uncomfortably. “I expect nothing less than full absolution in return.”

Wilibald shook his head in disbelief. “Your coin cannot purchase that which Christ’s blood purchased on the cross.”

Belame looked puzzled. He shot a glance at Robert who stood waiting, coldly half-smiling. Looked the young bowman up and down—recalling a boy watching his father die?

The provost called over to them, inquiring as to the delay.

Belame cursed, raised his bow, sighted the target, paused, and released his arrow. It struck the pin’s exact center.

The crowd, mostly Saxon socmen, burghers, and villeins, applauded, but no one cheered the Norman. Many shook their heads. Impossible to beat such a shot as that!

Robert prayed earnestly, wondering if it was proper to do so over a game, even one of such significance. He raised his bow, and the only sound was his arrow humming for the target. It struck the pin, cleaving it in three. Isambart’s arrow dropped to the ground.

The crowd went wild.

The older, more experienced bowmen, who had lost to Robert earlier, doffed their hats to him. Niles and his friends lifted him above their heads and carried him to the platform where the provost of the games waited with the prize, a silver penny. Over the heads of the crowd, Robert watched his father’s murderer mount his charger and ride off with his squire up the road to Lancashire.

An outdoor feast had been prepared, but Robert did not feel like celebrating. He used a sour stomach as an excuse and slipped off into Barnsdale as soon as he could.

Isambart de Belame was not the only one to leave the field unsatisfied.

Fountains Abbey, 1152

The following year, after Robert’s sixteenth birthday, Father Wilibald retired north to Fountains Abbey and Robert went with him. The Cistercian monks were greatly surprised to find that in addition to reading and writing Latin, Norman-French and his native Anglo-Saxon, Robert Hood could split a willow-wand at a hundred and fifty paces. Effortlessly!

“He has an eager mind,” Wilibald told them, “and a deft hand.”

Abbot Fastolf(20), a severe-faced Norman with dour, pursed lips, frowned deeply. "Archery? No fit skill for a monk," he said.

"A monk?" cried Robert. Shave the top of his head? Wear a coarse woolen habit? Take vows of poverty and obedience? And celibacy? He looked at Wilibald in dismay.

But the abbot placed a hand on Robert’s shoulder. "No fit skill for a monk, say I. But a God given skill for an abbey guardsman." His kindly eyes softened his unsmiling face. "Will you accept such a post, Young Master Hood, in return for food, lodging, clothing and study?"

Robert hesitated, a vigorous youth to be cloistered away for the rest of his days.

But Abbot Fastolf offered to add Hebrew and Greek to his languages. And Fountain's Precentor, the monk in charge of their small library, showed him copies of the early church-fathers' writings, Josephus' histories, and Bede's; and the Abbey's newest acquisition—a volume containing the exploits of Arthur, King of the Britons, written by a certain Geoffrey Arthur from Monmouth(21). Robert loved tales of King Arthur and his knights. Then Kalen, Captain of the Abbey Guard, a retired veteran of many a king’s war, offered to teach him the skills of a man-at-arms. This was all so much more than the only son of a youngest son, without lands or title could ever imagine.

That evening, Father Wilibald, his fingers trembling with great age and greater joy, hemmed Robert's guardsman tunic. "My little Rob, hiding in his hood, could scarce have imagined such a day as this, aye? The Lord is good, is he not, Rob?"

"That he is, Father."

"There now." Wilibald eyed his handiwork. "A dashing figure you cut in sword and helm, bow at your back." He clapped Robert's shoulder—the proud spiritual father.

Fountains' peace and scholarship suited Robert's temperament like a knight’s fitted armor. He missed Barnsdale, but loved the wide woodland downstream from the abbey. Sometimes he visited the milkmaids in the lower fields, interrupting their work.

"Guardsmen are not monks, mind you,” Father Wilibald told him one day. “They're free to marry, raise bairns unto the Lord. Wives and children board on the grounds in the new lay brothers' dormitory, you know."

Robert blushed.

"I know, Rob. I know. I’m a meddling old matchmaker!”

* * *

That same year, Isambart de Belame came to Fountains Abbey, and Robert resolved to exchange his new life for the homeless one of an outlaw.

Belame did not bargain with the Church this time. Simply opened the chest he had brought with him. It brimmed with silver coins. Ignorant of Belame’s crimes, Abbot Fastolf accepted his gift in Fountains’ behalf—that which Father Wilibald had refused in All Hallows’. Then, he freely absolved the knight, grateful for such benevolence.

Father Wilibald sought Robert at his station by the main gate. “The adder has grown crafty,” he would have commented. But Robert was gone.

“Deserted his post!” said Captain Kalen, disappointed in his newest guardsman.

Wilibald tottered, as though from a blow.

“He heard Belame would be leaving within the hour,” said the grizzled warrior. “Won’t stay the night in a house of God.”

Wilibald grasped the gate, stared through the grillwork. The empty road wound toward dense woodland in the gathering dusk. “I thought it was finished. Thought he had let it go.”

“Ought to warn Belame!” said Kalen. “Then again—“

Wilibald pressed his forehead against the cold, iron gate.

“Steady, Father,” said Kalen. “They’ll never catch him. Not Rob. Not in the wood.”

“But don’t you see?” cried Wilibald. “If he does this thing, it will change him forever.”

Bow in hand, Robert was out the gate and down the lane, racing along the way the knight would go. He darted into the forest and ran like a deer, down-river to a place he knew where the road dipped into a tree darkened cleft, before twisting out onto bleak moors. There he waited, hiding in the dense undergrowth above the road, face lost in the folds of Father Wilibald's old hood, arrow on string, not daring to pray or even acknowledge God’s presence.

The jangle of harnesses and tlot-tlot of hooves alerted him even before the knight and his retinue came into view. Robert raised his bow, drew the string to his ear. Belame rode at the head of his men. A clear shot! And Robert would vanish before the men-at-arms could react.

Belame deserved to die. After the shooting match, news at the Blue Boar Inn had always included his latest crimes for which no assize ever summoned him. So much for Norman justice! Well, here was Saxon justice, served at arrow’s point.

Belame was directly beneath him.

Robert’s fingers trembled on the string. He did not have to do anything to slay his foe. Just stop what he was doing—holding the string—and the arrow would pin his foe’s evil heart.

Sir Isambart de Belame, at the head of his men, rode on, passing out of the wood.

Robert lowered his bow.

Oddly, a weight lifted from his shoulders.

He bowed his head as night fell.

Father Wilibald and Captain Kalen were waiting for him back at Fountains’ torch-lit gate.

“No missing arrow,” Kalen observed. “Is it possible?”

“All things are possible,” said Robert, winking at his foster-father, “with God!”

Wilibald stretched up to embrace Robert. “You are free, my son, unlike Belame.”

“Free?” Kalen exclaimed, trying to sound angrier than he felt. “Not of a week’s worth o’ double duty for desertion!”

Endnotes:

1. Sir Clee Pearson’s investigations into each letter’s historical context (place names, allusions and attitudes), textual context (dialect, spelling and cursive hand), and material context (inks, parchment and binding) have authenticated the Clerk of Copmanhurst letters as early 13th century documents, predating all extant versions of the tales and, ironically, influencing many of them. Even our mysterious clerk’s pseudonym reappears as the outlaw band’s spiritual shepherd as late as 1819 in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. See: Pearson, Sir Clee. Sherwood Tales: The Clerk of Copmanhurst Letters, Annotated. Halifax: Furness and Sons, 2007.

2. Sir Walter Scott wrote much of Ivanhoe at Fountain Dale House near Blidworth, Nottinghamshire. He referred to the Fountain Dale area as Copmanhurst for reasons unknown until the discovery of these letters. Why our Clerk chronicler calls his retirement cell Copmanhurst is still a mystery. Did he, in fact, return to Fountain Dale, or was Copmanhurst located elsewhere?

3. The Clerk of Copmanhurst uses the term English here and throughout his letters. Sometime prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066, the three Germanic tribes (the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes) began referring to themselves as English. However, since the 14th century, the Clerk’s time period has been referred to as Anglo-Saxon, his language as Old English, and his people as Saxons. Likewise, the Normans referred to themselves as French. I have translated the Clerk’s ‘Englishman’ as Saxon, and ‘Frenchman’ as Norman because of their familiarity to modern film audiences.

4. One of the first dry-stone wallers. The Yorkshire countryside’s distinctive characteristic, its low, mortarless stone walls dividing hill and dale into a patchwork quilt did not exist in the Clerk of Copmanhurst’s time. His allusion to this ‘new’ technique is one of many details used by Sir Clee Pearson to historically place and validate the Clerk’s letters. [Pearson, Sir Clee. “Robin Hood: Fact or Fiction?” Yorkshire Digs: Overturning History 80 (2005): 32-49.]

5. The tanning, dyeing and spinning industries were well established by the 1200s according to “Medieval Wakefield Unearthed by Sheffield Experts”/ 19 December 2006 at www.shef.ac.uk/mediacentre/2006/709.html

6. As is characteristic of Old English, even as late as the 12th century, the Clerk’s writing does not contain contractions. I have therefore used them sparingly where they would naturally occur in modern usage, mostly in dialogue for the purpose of characterization.

7. villeins: serfs, often hardly better off than slaves, tied to the land and the lord of the manor, having their own small track of land and serving on the lord’s land three days out of each week (often to the neglect of their own)

8. socmen: natives of a shire who own their own property

9. burghers: townsfolk

10. Here are further details aiding the modern scholar in his quest to repudiate the skeptic. The printing press was not invented until c.1450, and bookbinding was in a primitive state prior to that.

11. The Clerk’s letters support modern research confirming that the longbow originated in Wales and was not in general use prior to c.1250. A band of determined longbow men, like those later belonging to Robert’s son, would have been unique in their day and could indeed have held armies at bay from forested safety. Because of its power, range, and re-firing speed, the English longbow has been called the machinegun of the middle ages.

12. Elwyn the Welshman is mentioned as a contestant in the famous shooting match scene in both J. Walker McSpaddon’s Story of Robin Hood and His Merry Outlaws (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1904) and Warner Brother’s 1938 Robin Hood starring Errol Flynn. Similarities between the two indicate that McSpaddon’s version influenced screenwriters N. R. Raine and S. I. Miller. Did McSpaddon have access to copies of the Clerk’s letters? Was there an independent Elwyn the Welshman tradition in balladry since lost? The Clerk’s history offers little additional information.

13. The appellation ‘merry’ was often used in regard to Robert’s hometown, not surprising since Wacanfeld (Wacca’s Field) had long been the site of rural festivals known as ‘wakes’.

14. Hamelin Plantagenet, half brother to Henry II, became the fifth Earl Warren and Lord of the Manor of Wakefield in 1150 by marriage to Isabel, the third earl’s daughter.

15. Was Isambart de Belame a descendant of Robert de Belleme, Earl of Shrewsbury, the brutal warrior and cruel lord who rebelled against Henry I in 1102? Belleme’s castle and estates were confiscated by the crown, and he was banished for life. The name Isambart, however, does not appear in Belleme lineages.

16. If this is a descendant of the notorious Robert de Belleme, he might well have recognized a Welsh design, the family seat having been Arundel, from which they harried the Welsh, seizing much of their land.

17. butts: archery targets made of compacted straw with earthen mounds for backing

18. pin: wooden peg marking the target’s center

19. honour: a baron’s holding

20. Richard Fastolf, Abbot of Fountains Abbey from 1148 to 1170.

21. Undoubtedly, an early copy of Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain), by Geoffrey of Monmouth, one of the earliest British historians (or the first British historical fiction writer, depending upon the modern scholar one consults).

G. K. Werner teaches English, history and martial arts when not writing genre fiction from a Biblical perspective. In addition to Lacuna, his stories have appeared in Tower of Ivory, The Sword Review and Fear and Trembling. He lives in ‘slower lower’ Delaware with his wife, author,poet, songwriter and homemaker Virginia Ann Werner (who taught him story telling), their collie and cats (who don’t write but have strong opinions).

Where do you get your ideas for your stories?

For some reason, I read Shakespeare comedies while writing Robin Hood tales, and draw (no pun intended) on the original Robin Hood folk ballads as preserved in the 16th and 17th century plays and broadsides, as well as the Victorian era adventure books.

Often reprinted and still the best:

Robin Hood and the Men of the Greenwood by Henry Gilbert (1912), illus. by Frank Godwin

Robin Hood and His Merry Men by E. Charles Vivian (1906), illus. by Harry G. Theaker and Jules Gotlieb

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire, written and illustrated by Howard Pyle (1883)

Maid Marian by Thomas Love Peacock (1822)

Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott (1819), illus. by N. C. Wyeth

0 comments:

Post a Comment