Breath of Amun

by Karen L. Kobylarz I awoke to a shout and a

hiss-whump breaking through the gentle rustle of the trees. My hands tightened around the arms of my chair, and I sat up, heart racing. Another cry from the guards on the walls told me the enemy had come. The Desert-folk, attacking the palace garden in broad daylight. Only Nahman, their serpent-spawn sorcerer, servant of Apepi, King of Thieves, would be so bold.

Where was he? His men? They could not be far. Where—

There, in a pole of the canopy I rested under, an arrow shaft quivered. An arrow, a mere arm’s length away, so close, even this old woman’s eyes could see it.

Hiss-whump. Another arrow struck, this time into a nearby sycamore trunk. My body tensed as memory stirred, unfurling images of a battlefield and my father, grandfather, uncles, brothers . . . Run. I had to run, had to—

I scrambled off the divan, my body protesting each move.

My fanbearers ceased their work and closed in around me, clutching their fans as if they could protect me from more than the day’s heat. The bearer at my right leaned toward me. “Lady Tetisheri?”

Voices rose from inside the palace, soon joined by the thunder of footfalls, and within heartbeats, royal guards spilled out along the garden path to join the others on the walls. Tree branches stirred and cracked; another volley of arrows sliced the air.

Our men charged forward, up the narrow stairs leading to the top of the wall. One of the fanbearers seized my shoulders and shoved me under the divan. My world dissolved to one of shadows, feet, and legs. As more arrows hissed our way, my bearers crouched down beside me, blocking what remained of my view.

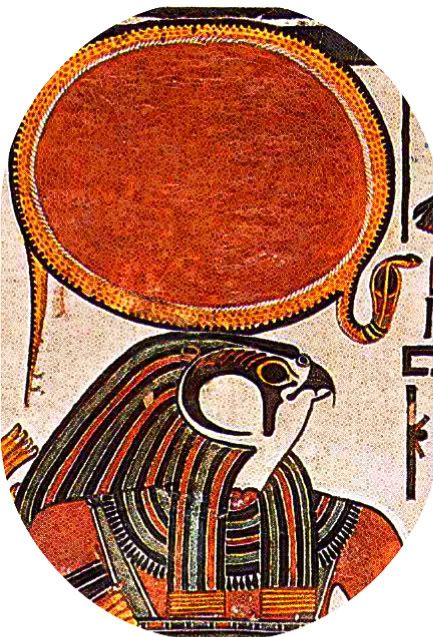

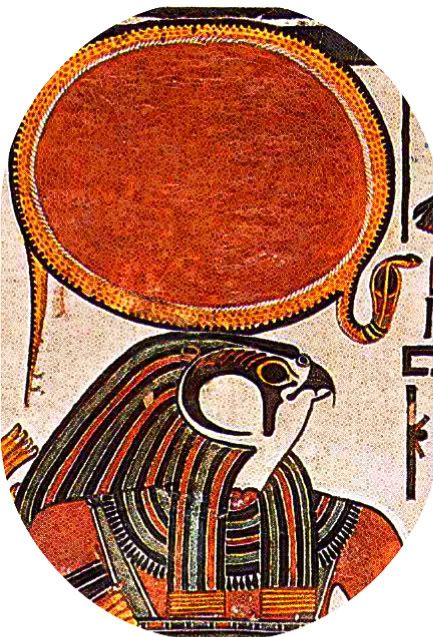

“Forward in the name of Ra Sun-Lord!”

“Hor Falcon-Lord, defend us!”

More soldiers ran to the wall, only to have their prayers choked off by Desert-folk arrows. Why invoke the names of gods who hadn’t answered our prayers for over fifty summers? Gods who left us nothing but death!

I clenched my fists, grit my teeth, and willed a thought in the direction of the enemy.

Leave us alone. We surrendered half our country to you. Be satisfied. “For Amun the Creator and victory!”

My head hit the underside of the divan. Demons of the Netherworld, was that

Kamose?

No, my grandson would not be foolish enough. His father wouldn’t let him.

“Sa-Ibana, with me,” Kamose called out to his friend from the guard. “To the walls, men.”

To the walls? An invisible hand clutched my heart, but I shook free of its grip. Crawling out from under the divan, I pushed my way through the cluster of fanbearers. Where was Kamose?

There, to my right, with leather armor over his white tunic, quiver of arrows on his back, bow in hand.

I dashed after my grandson as if I was still the ten-year-old girl who had followed

Atta, Grand-

atta, and the others when the Desert-folk first encroached upon our lands.

Branches tore at my dress, cornflowers tangled my feet, and guards brushed against me as they hurried to join him.

As Kamose reached the first step, I clutched his tunic and pulled. We both fell back, sprawling to the ground.

“Kamose!” I kept my grip on him. “Are you mad?”

“Grandmother.” He sat up and tried to yank himself free. “For the love of Amun, we can’t sit in the palace and do nothing.”

I tightened my hold on him. “We cannot die.

You cannot die. Did you never listen when I—?”

“Yes, yes.” Kamose frowned. “The same old story about your father and grandfather and brothers and the Desert-folk.”

An arrow whooshed over us, grazing my hair. I pushed him flat to the ground. “You need to hear it again.”

“Not now.” He shoved me aside, sprang to feet as his namesake had done years before.

My little brother’s voice still haunted me.

“Hurry, Tetisheri. Let’s follow Atta

and the others. We’ll get to see a real battle.”We had been so certain then. The gods were with us. The Desert-folk had driven us from our North Land, but with strength in numbers, we would take it back. So

Atta had said. So Grand-

atta and our uncles had said as they and our elder brothers marched off with the army.

My little brother and I waited until they had almost disappeared from sight and crept after them. We found an unguarded spot along the city wall and climbed to the top. On the other side, our army waited for the foe, bows and spears and swords ready.

A dust cloud rose on the horizon, and silence fell. As the cloud came closer, closer, thunder roared. Darkness swallowed all of them. Though my brother and I strained our eyes, nothing but yellow-gray dust spun below us. Shouts rose, then cries, yells, screams, whimpers.

The cloud lifted even higher, rolled toward us. My brother and I ducked for fear it would swallow us as well. But it stopped when it reached the wall, hovered as if examining us, then retreated. As it neared the ground, the cloud became a crimson haze, and from it lanky figures emerged: Desert-folk tramping amid the bodies of our soldiers, the once-dry earth soaked with blood.

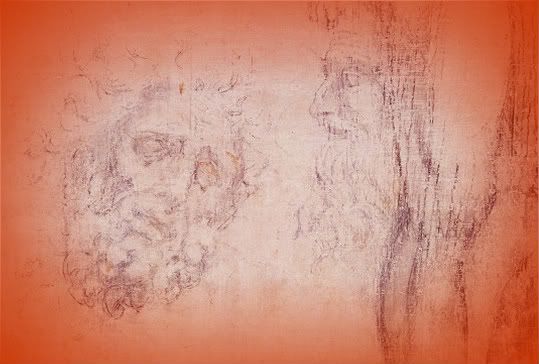

In the center of the carnage, a tall, thick-limbed man stood in a chariot. Obsidian-black steeds crowned with red feathers stamped before him. Cloaked in silver, he surveyed the other men, arms folded across his chest, remnants of the dust cloud lingering at his shoulders.

I had straightened for a better look at him, and my little brother had followed my lead.

The man raised his head. Dark eyes fixed on me, and he pointed my way. The Desert-folk archer nearest to him fired his bow. The arrow shot toward us. I ducked; my brother didn’t.

I caught him before he fell and eased him down upon the top of the wall. The arrow had lodged itself in his right eye, and blood poured out faster than tears. His breath came in short gasps, and as I searched frantically for someone or something to help us, a dust cloud danced close by.

When I turned, the thick-limbed man crouched beside me, a dagger as silvery as his cloak in one hand. “Come, child. I am Nahman.” With the dagger pressed to my throat, he brought me down from the wall.

He had guided me to my father’s body, flayed the corpse before my eyes, and ordered the same done to all our men. He had left them for the vultures, setting up a guard to stop those who might try to recover the remains.

I shuddered at the memory and grasped the end of my grandson’s tunic. “I won’t let them do that to you. I won’t.”

“

Won’t?” A whisper came with a questioning ring, and warmth rushed over me.

Strong hands seized my arms, pulling me away from Kamose, and Sa-Ibana’s voice filled my ears. “Stay here, Lady.” Then he, Kamose, and half-a-dozen more guards raced up the stairs to the top of the wall.

No, not the wall. Arrows flew over the wall, and it would only take one. One arrow, and my brother had fallen, my brother had died . . . On a wall. Because we climbed the wall . . .

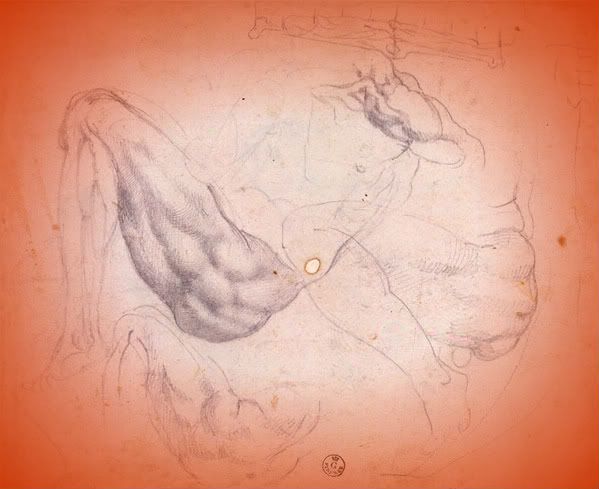

I followed them as fast as age would let me. Archers stood aligned, raining arrows down on our attackers. Below, more of our men brandished their straight swords against the sickle-shaped blades of Desert-folk soldiers. The air had thickened with their magic, even though today Nahman did not walk among them. The land had turned into a swirling mass of men and dust and blood.

Several nearby guards noticed my arrival and hurried to my side, covering me with their shields as another swarm of arrows sped our way. When it had passed, I peered over the shields’ edge. Our swords scratched the enemy and nicked their shields. Kamose and Sa-Ibana knocked their bows and fired. But their arrows sailed no further than a child could fling a stone, one grazing the side of an enemy soldier, the other bouncing off a shield.

The majority of Desert-folk soldiers kept well out of our range. But their arrows found us, and in combat the sickle blades of their swords hooked on our shields, forced them down, and sliced our men’s throats.

A hand gripped my shoulder. “Come down now, Mother.”

I spun around and glared at the man standing before me, his gold-threaded kilt glistening in the daylight. “Why? They’ll defeat us whether I stand here or not!” He may have been Lord of the South for the past eighteen years, but Tao was still my son. “Take a look for yourself.” I waved a hand at the battlefield. “We might as well be fighting with pebbles and cattle prods.”

Tao’s usually amber-bright eyes darkened. He opened his mouth, but a distant rumble tore his attention away. Beyond the embattled troops, came a Desert-folk chariot. A lanky man with a fine cloak draped over his armor clutched the reins. He stopped well out of our arrow range and lifted his chin. “Hear me, Vassal Tao! Apepi, King of the North, sends you this warning: The hippos in your eastern canal have been bellowing too loudly of late. They disturb the Great King’s sleep. Remove them at once, or Nahman will come.”

Kamose shifted the quiver on his shoulder, revealing another bow beside it. He cast aside the bow in his hands and took up this one. Beside him, Sa-Ibana did the same.

“Wait!” Tao held up a warning hand.

Kamose clenched his jaw, his fingers drumming against the bow—a bow with a band of wood that curved in the middle ever so slightly. Why wasn’t it straight like the others?

Before I could ask, Tao stepped forward and tapped Kamose’s arm. My grandson fired, and the arrow soared over the Desert-folk ranks, striking Apepi’s herald below the neck. The man slumped over the chariot frame.

Tao grinned. “Now, desert bows!”

Our archers cast aside their straight bows and armed themselves with curved ones. Below, our swordsmen fell back, and a familiar thunder filled the air.

I reached for Tao, my heart like a stone in my chest. “Nahman.”

Tao’s smile didn’t fade. “Not this time.” He turned to the men. “Fire!”

The archers obeyed, the arrows from their new bows flying deeper into the Desert-folk ranks. A second magic cloud rose around the palace as chariots bearing

our men, charged the enemy from either side. Another wave of our soldiers followed, armed with the same sickle-swords the Desert-folk wielded.

I stared across the battlefield, my pulse regaining its rhythm.

How?The enemy fell back; their cloud wavered. Desert-folk soldiers flung down their weapons and fled.

Soon, all were retreating, many bleeding from multiple wounds.

One straggler turned and shot single arrow our way. It whisked between Tao and Kamose, and stabbed into the ground below. The sun, which our ancestors had named Ra, shone down upon the weapon, turning its pale wood a dazzling white.

Scrambling down from the wall, Kamose yanked the arrow from the earth.

Tao and I followed.

“

Nahman will come.” The whisper brushed my ear, rising above the groans of the wounded. I turned to seek its source.

Guards gathered around us. “What was the meaning of that? The man, his warning—” I jabbed a finger at the wall, my blood chilling with realization. The Desert-folk capital was a good ten-day journey down the River, too far for anyone to hear hippos in our canals.

My pulse pounded in my ears.

Some-thing-else, some-thing-else. A threat lurked behind those senseless words.

“Tao?” I grabbed his hand, squeezing his fingers until my knuckles whitened. “What have you been doing? Those bows and chariots and swords . . .”

Tao sighed. “I’ve been putting them to good use, and trusting in Lord Amun.”

“Amun?” I spat. “That god has done nothing,

nothing.”

Tao’s lips thinned.

If only the gods would grant me power to read his thoughts, I might believe in them again.

“

Believe again.” The whisper taunted me once more, and a fly tickled my neck. I shook my head to banish them both.

“The hippos.” I clutched the broad collar around Tao’s neck. “He means you, doesn’t he? You’re encouraging our people to take up arms against him.”

An amber glint came into Tao’s eyes. “It seems I do bellow loudly.”

An uneasy chuckle made its way through those gathered nearby.

Tao placed a hand on mine. “All the stories about Nahman and his magic are just that—stories. The Desert-folk’s real power lies in their weapons. They were able to drive our forefathers from the Northern Land by using better weapons.”

I stepped away from him, a silver dagger and flayed corpses lingering in my heart. “Don’t dismiss the stories. I’ve seen what Nahman can do, the sandstorms he raised.”

Tao laughed. “Magic alone doesn’t give the Desert-folk their sandstorm speed. Chariots do, and we now have some of our own, as you have seen.”

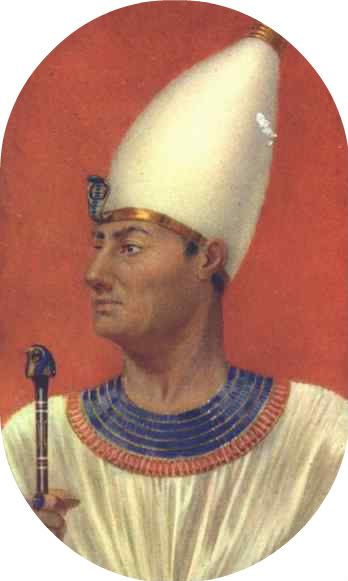

He turned to Kamose and took the arrow from him. “My years on the throne have not been idle. My border patrols collected Desert-folk items, and men like Sa-Ibana studied them.” He nodded at Kamose’s friend. “You’ve seen what we have, Mother: their bows, chariots, sickle-swords, and armor. I have been working on this for over twenty years, even while Father still lived. Yes, we must be wary of Apepi and his people, Nahman most of all, but we cannot fear them forever. It’s time to win back our Northern Land.”

Heart pounding, I stared at him. Though a thousand questions filled my thoughts, only one made it to my lips: “How do you know it’s time?”

Tao drew closer, his irises burning like two golden suns. “When I was Kamose’s age, I went to the Mansion of Amun before sunrise and joined the priests in their morning ritual. I heard a voice telling me the time would come. It commanded me to learn the secrets of our enemies and prepare the Southern Land for war. The gods have not deserted us.

Amun has not deserted us. We can defeat the Desert-folk. Amun Himself told me I would know when it was time. It

is time, Mother.”

My lips pressed together so hard they numbed. “I don’t believe you. I cannot. Where was Amun in the time of our forefathers, when the Desert-folk came and drove them from the North? Where was Amun the day Nahman breached the borderland wall and slaughtered our men? Where was He when the Desert-folk shot my little brother and—?” Sorrow choked my throat, and tears stung my eyes. “Where was

He when your father’s father was forced to grovel at Apepi’s feet?”

Taking my hands in his, Tao drew me back into the present. “Mother, He is here now. He has always been here. It is we who have failed, we who have lost faith. Come with me to Amun’s Mansion tomorrow. You will believe.”

* * *

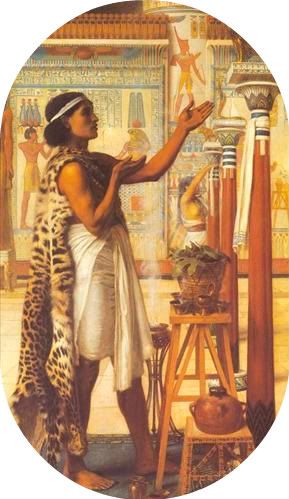

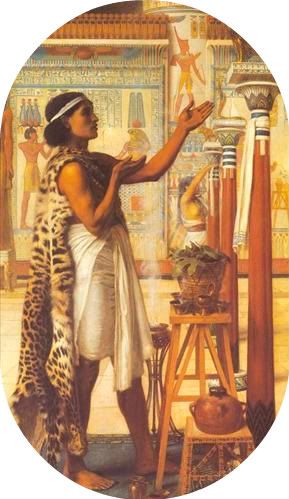

* * * Tao and I came to the Mansion of Amun moments before dawn. Murmurs arose amid the gathering of priests, musicians, and torch bearers waiting there. The Lord of the Southern Land rarely joined them in their ritual; the Lord’s mother never had. We waited, until the sun’s first rays pierced the horizon, tainting the east with a thin line of blood. The lead musician began shaking her sistrum, two priests opened the Mansion doors, and Tao entered, followed by the First Prophet, then me. Behind us, musicians and priests struck up a chant of welcome to the reborn sun.

At the entrance, the ceiling soared above us, balanced atop walls and pillars that reached up like lotus petals welcoming the light of the sun. A hundred colors, shades of red, yellow, brown, green, and blue seemed to blaze off the whiteness of the stone—a white purer than ivory, dazzling my failing eyes in the early morning dreariness. The newborn world must have been this bright on the first day of creation. Among such hues, a god might be near.

Might.

We moved onward at a stately pace, suited for honoring the god and for an old woman’s legs. The musicians’ hymn bounced from pillar to pillar. Our path rose ever upward. My calves began to ache. Above, the ceiling dipped down. A dozen pillars became a hundred, gathering around as we moved in deeper. Darkness snatched the white away, leaving me half breathless. Was it much further? Why had I agreed to this? To feel a so-called

presence? Why would the god come after so many years of silence?

Another doorway opened before us, almost invisible in the gloom. Here, the priests prepared the offering, fogging the air with incense. Smoky gray and the smell of bitter-spice mingled with the music and assailed my nostrils. I breathed in and coughed. Why would a god come for

this? Incense and song battered against the night. Beneath this attack, the darkness faltered, lifted one handwidth, then another.

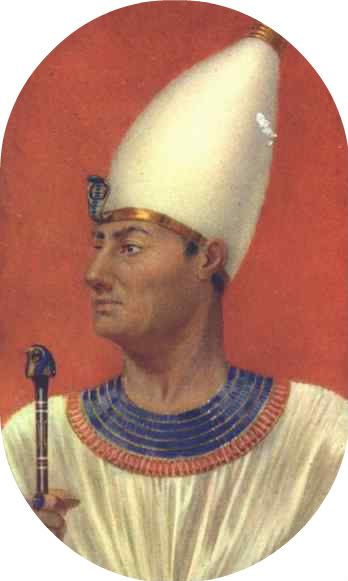

Taking the offering, Tao passed through the doorway to the sanctuary hidden beyond, the First Prophet and the chief musician at his side. I stood ten steps behind them. Tao reached out and touched the darkness. A beam of light from the east slid across the floor and up, up, until it caressed his outstretched hand. My heart thundered in my ears. Morning magic crackled in the air, unseen doors thunked open, and the image of Amun, Eternal Lord of Creation, shimmered, his right arm extended, bathed in newborn sunlight.

“Amun,” I whispered the name, shivers dancing across my skin.

The chanting grew louder, and the Mansion roared a joyful welcome to the Creator as if he had truly come.

Breath, hot as the noonday sun, grazed my neck. My skin prickled, and I glanced back, ready to scold the idiot priest who would dare play games with me, but—Nothing. No one was there. The priests had vanished into the field of lotus-columns. The breath brushed against my neck once more. “Who’s there?” I turned around.

No one.

“Tetisheri, who is Ra?”

Something about the voice chilled my flesh, dried my throat. I swallowed hard. “Ra?” The old god of the sun? He had deserted us, as Amun had.

“No.” The voice came wind-whisper soft, its owner reading my thoughts. “He is here with me.” Another breath rushed over my neck and down my back, following the path of my spine. “I am the Creator. I am Amun, and I am Ra.”

I shook my head. He was Amun

and Ra? How could one god be another? “Show yourself!” The priests were playing games with me, that was all.

Laughter rippled the air. The voice came louder and clearer now, its words flowing like river water. “Tetisheri, Mother of Kings, is that what you want from me?”

Tears stung my eyes. My hands balled into fists. “Yes, let me see you! Tell me where you were fifty years ago when the Desert-folk slaughtered our men. When—”

When my brother bled to death on the wall? Something touched my cheek, lifting away a tear.

The laughter faded. “You want easy answers.”

The voice fell silent; moments passed. Had the speaker fled? I peered into the mix of light and shadow, hoping to catch a glimpse of something.

Nothing.

“I am

Amun-Ra, the Hidden One and the Visible Sun!” The words came with such force, I stumbled backwards. “By my will, the foreigner shall be ground to dust by weapons of his own making.”

I stared into the darkness, my breath caught in my throat. Could it be? Would He really appear after all this time, as Tao had said?

Tao. My lips curled. How conveniently the god echoed the wishes of my son.

A low chuckle rose from the darkness. “I

am Amun-Ra. Long have I waited to do battle against enemies of the Two Lands, for the right vessel through which I could enter your world.” Rays of sunlight rushed before me, gathering together, pouring down like a golden waterfall. The light took shape, the form of a boy with an arrow through his eye.

Then arrow fell away, and the eye healed. The boy grew into a man wearing the Double Crown of a king of a united Two Lands. Amber eyes stared out from a gilded face. Eyes like Tao’s, but the face . . . so bright. His right hand clutched a dagger, not by the hilt, which was covered in gold and inlayed with chips of red jasper and lapis lazuli, but by the blade. He held it out to me. “You have readied that vessel for me at last, Tetisheri, Mother of Kings. Strength and victory are my gifts to your House.”

Heat poured from Him, driving me to my knees. My body shook. My heart slowed; my breath came in gasps. The god

was here, before

me. The god was . . . truly . . . and my son would be his vessel. I prostrated myself and awaited His command. “What do You desire, Lord?” My heartbeat faded to a faint pulse, and my blood filled with a winter’s chill. “How can I help make your vessel ready?” If Tao could drive Apepi and Nahman from our lands . . . “What sacrifice do you need?”

“No, Tetisheri, not sacrifices. Faith. Believe my words. If the flesh of your flesh bleeds, I shall bleed also. The blood of a true king will destroy the greatest weapon of another. From the blood of Nahman’s slayer shall come not mere kings, but

Per-aa, a Great House that shall rule over the Two Lands for generations to come.”

A hand touched my head, and I lifted my eyes. My breathing eased, and warmth flooded through me. The voice and image faded, but His final words lingered in my heart.

“Mother!”

I turned toward the cry.

Tao was rushing to me. “Mother, are you well?” He knelt down, his eyes dark with worry. “Did you sense Him?”

I shook my head. “More than that. I

saw Him. I heard His voice.” I swallowed hard and met Tao’s gaze. “You were right, my son. Amun is with you.”

He clapped his hands, triumph rising in his eyes and in his smile. “As the god wills it. The next sound Apepi will hear will be the roar of

our chariot wheels.”

* * *

* * * Yellow dust rose in the distance as the enemy approached. From atop the city gates, I watched them, a three-man guard with me. Below, Tao took his place in his chariot, his cloud-white horses stamping the earth. A company of sickle-swordsmen surrounded him, the polished leather of their armor reflecting the sunlight. Behind them lined the common ranks, loincloth-clad, gripping straight swords and leather shields. Kamose joined the left flank of our army. Sa-Ibana joined me atop the walls with his archers, many armed with Desert-folk bows.

For months, Tao had sent Sa-Ibana and our elite forces into Desert-folk border towns, destroying everything and bringing enemy survivors to our capital in chains. Then we had deliberately fallen back, let Apepi’s army through. Hadn’t Lord Amun promised us victory? And where better to win it than before His city?

The enemy drew nearer, and Tao unsheathed his sword. “This day Nahman himself shall die in the sight of Amun-Ra!” A single stroke down, and our army charged. I gripped the protective wall. The drum of horses’ hooves sounded in my ears. The armies met in a thunderclap, a mass of humanity, chariots, horses, and metal. Men fell on both sides, splotching the ground with an all-too familiar shade of red. But Tao stood tall, and so did Kamose, their new curved blades tearing down enemy shields and slicing deep into Desert-folk ranks.

I waited, my body quivering, my fingers growing numb. The dust thickened. Cries filled the air: voices of the dying. Desert-folk or ours? I raised my eyes to the heavens. Ra shone down in a dazzling white ball. Where was the breath, the touch of Amun on my neck? Amun and Ra—they were one.

My guards and Sa-Ibana’s men grumbled and fingered their bows. Thudding hooves, growling chariot wheels, clanking swords, shouts, screams.

Sa-Ibana signaled the archers.

The men raised their crescent-shaped bows and fired. Arrows showered deep into the Desert-folk ranks. The enemy faltered and began to retreat.

“Look, Lady!” A guard’s voice rose above the fray. “Something comes.”

Another chariot hurtled out of the north, bearing a single rider cloaked in silver. Arrows flew his way, only to drop to the earth before reaching their target.

Nahman.

Dust-filled air and flashes of sunlight on metal met my eyes. Tao and the others vanished in a sandy haze.

My heart pounded as if it longed to break free from my chest. One beat. Two, three, four, five . . . one hundred. At last they emerged from the dust: our men running toward the walls. A familiar voice reached my ears. “You and you, with me. We must open the gates. The rest—cover us.”

Sa-Ibana. He bolted from my side and to the stairs. What had happened to Tao? Kamose? The aches of age slipped away. I rushed down the steps, after Sa-Ibana. When I reached the ground, I headed for the gates, battle dust swirling around me, the guards at my heels. Soldiers ran past, their eyes wide with fear. My feet slowed and finally stopped. Pain, low and dull, throbbed in my bones. My lungs heaved. “Sa-Ibana! Sa-Ibana, answer me!”

“Lady.” A rough hand grasped my arm. “Go to the palace. Nahman is victorious. We can’t find the king or the prince.”

A chill raced through me. Couldn’t find them? Before I could question him, Sa-Ibana dragged me away from the gates, down the road toward the palace. A stream of bodies flowed around us, panting breaths and thundering footfalls. Ra was in His heaven, but Amun . . . Where was Amun?

“The god’s Mansion.” The answer came to my lips. I tugged Sa-Ibana’s arm. “We must go there. The god will protect us.”

Sa-Ibana repeated my words to the others and together we made our way to the Mansion. We ran to the gates, and they swung open.

The shadows of the torch-lit hall gathered around us, as did priests, chanters, musicians.

Sa-Ibana turned to the soldiers. “Bar the gates and line the hall, both sides, ten paces apart, weapons ready.”

The First Prophet approached me, his hands shaking, his face pale. “My Lady?”

I didn’t answer at first. Amun-Ra had promised victory. Amun-Ra would know what to do. I grasped the First Prophet’s wrist. “We must go to the sanctuary.”

The man stared at me, his mouth gaping. Angry shouts erupted from behind the gates. There came a thud, then another. The plank of wood barring the gates shuddered.

I tightened my grip. “Now!” Without waiting for him to obey, I hastened down the hall. “Sa-Ibana, all of you, come with me.”

The hallway threatened to slow me down. The floor slanted upward, and columns closed in on all sides. Darkness gathered, punctured only by a handful of torches. But Sa-Ibana and the First Prophet, who had recovered his wits, took hold of my arms and propelled me forward. Soldiers and priests crowded around us. Thunks and cracks echoed behind us.

We reached the sanctuary door, and the First Prophet flung it open. “May Lord Amun forgive this intrusion.” He stepped aside for me.

I approached the gilded doors Tao had opened months before. They gleamed orange in the torchlight, needing Ra’s light for their true golden glow.

Another crack, a groan, the tramping of hurried footsteps. The Desert-folk had breached the gate and were coming our way. Bodies pressed against me. Sa-Ibana’s orders lashed against my ears. “Take up position! Form rows, shoulder to shoulder. Shields up!” The priests called to Amun.

I reached out and flung open the doors.

A wind rushed into the sanctuary, cold as the north breeze at night. I turned to face it. It bit into my skin. Dust filled the hall and the sanctuary, choking off priests’ prayers and soldiers’ curses. The men forming the first row drew their weapons and swung, only to have sand grate against their blades. At last, the wind began blowing in circles, gathering the dust together in a tall, thick cloud before our first line of men.

The cloud took shape, rounding at the top, splintering lower down into limbs, fingers—a human form. Amun-Ra?

I hissed in a breath as the cloud solidified into a man with thick-boned features and silver cloak.

Nahman, unchanged from when I saw him last.

The sorcerer held up his hands. “Disarm yourselves, people of the South! We have your Lord and his heir.”

Desert-folk warriors poured in behind him, two dragging my grandson between them. Kamose’s hands were bound behind his back, his scalp cut and bleeding, his eyes blackened.

I stepped forward, trying to push through the crowd of priests and soldiers. A hand came down on my shoulder, and the First Prophet’s voice brushed my ear. “Lady, don’t.”

I stopped and turned my eyes to Nahman. The air grew heavy with the smell of sweat and fear.

The sorcerer smiled and inclined his head in my direction. “Old woman, tell these fools to do as I say.”

I swallowed hard, dryness filling my throat. “Where is my son?”

Amun-Ra, where are You?

Nahman motioned to his men. Four of them came forward bearing a shrouded pallet. Our soldiers and the priests drew back as they set it before me. At a word from Nahman, they pulled back the covering.

Tao lay there, as he had appeared only once before. On the day of his birth, the midwife had held him up, a little squirmy thing, muddy red. He’d cried and thrashed when she’d washed him. Then I’d held him for the first time, and he’d reached out with a tiny hand. . . .

Now Tao didn’t cry, his body frozen in a final thrash. An arrow had claimed one amber eye. Others pierced his arms, and in his neck, a dagger with inlays of jasper and lapis lazuli, like the one Amun had offered me. And silver, like the one Nahman had pressed against my neck years ago when he made me watch—

The world blurred in a crimson cloud. My stomach clenched. My knees gave way. I fell to the floor beside my son. I stroked his forehead as I had done so many times when he was a boy.

Tao, my son, my boy, my baby, so full of promise.

Promises.

Amun-Ra had made me a promise.

I lifted my head and turned to the sanctuary. Between the open doors, the statue of the god stood, gleaming dully. The crook of kingship rested in His right hand, the crown of the south upon his head. His lips curled in a gentle smile.

Smile? How dare He smile? No sacrifices. He’d promised me.

My hands curled into fists. Something more than blood coursed through my veins. Hate.

Curse You, Amun-Ra. Liar! Traitor! My gaze fell upon Tao, the blood, the arrow shafts, the dagger handle.

Nahman made his way among our men. “Surrender, men of the South, or your prince will share his father’s fate.” He waved a hand at Kamose. Desert-folk warriors forced my grandson to his knees. Another held a sword to his neck. One by one, Sa-Ibana and our soldiers cast down their weapons.

No. Surrender was not in the promise. Neither was defeat. A god who couldn’t keep His promises was no god, but a Netherworld fiend.

I reached out, gripped the handle, pulled the dagger free. The dagger of Nahman, stained with the blood of

my son. I struggled to my feet and rushed to the statue of the god. I raised the dagger, aiming for the neck.

Have faith, Tetisheri. Warmth washed over my face and trailed along the back of my neck, a tickle, a puff of air, the breath of Amun, who was one with Ra.

“Lady!” The First Prophet’s voice quivered with horror.

I drew my hand back. Too late. The tip of the dagger grazed the statue, marring the gilding. Liquid gold oozed from the gash like blood.

Blood of the gods.

I pressed my hand against the wound.

If the flesh of your flesh bleeds, I shall bleed also. Nahman’s laughter filled the hall. “See the end of your royal house, men of the South.”

Tetisheri, Mother of Kings. The voice of Amun-Ra rose above the sorcerer’s words.

Strength and victory are my gifts to you. His blood burned against my palm. His breath touched my neck and hastened up my cheeks to my nostrils. I breathed deep, taking Him in.

Footsteps behind me, a cold hand on my shoulder. “Come with me, old woman.”

Old woman? No, not I, not now. I had once dwelt in the watery abyss, tamed it, changed it, shaped it into the world that was. I had swum across the surface of the sun, sailed amid moonlight and stars, and danced in the dust of the earth. I was the air stirring that dust, the breath giving life to Sa-Ibana and Kamose, to Apepi in the distant North.

To Nahman.

The hate in my veins boiled into fury, a divine rage, numbing age and pain. I was Tetisheri and Amun and Ra, and what had been given, I could take away.

As Nahman tightened his grip, I turned to him, dagger in hand, a promise on my lips: “The blood of a true king shall destroy the greatest weapon of another.”

Amun-Ra poured out of me, into the weapon, the Creator of Life becoming death. The air pulsed with light. A single stroke to the neck, and Nahman’s blood mingled with Tao’s.

I released the dagger, its hilt silver no longer, but as gold as the blood of a god. The sorcerer collapsed at my feet.

Cries filled the air, those of triumph and disbelief. Sa-Ibana retrieved his sword. “Men of the South, take up your weapons!”

Our soldiers followed his command.

Some Desert-folk warriors fled. Others stood, staring wordlessly at the body of Nahman, at Amun-Ra, at me. One warrior swung out with his sword. Amun’s priests gained courage, rushed at the man, dragged him to the ground. Too late.

Kamose had fallen.

No, Lord Amun! No! I raced to him and knelt by his side. “Kamose!”

“Grandmother?” The sound came, half word, half cough. Kamose raised his head, scalp still bleeding and face bruised, but no other mark on him.

Tears rushed to my eyes, and with them flowed relief. I touched my grandson’s cheek. Lord Amun had spoken true. Kamose, child of my blood, lived.

“My Lady?” The First Prophet came to me, and the other priests drew around us. The shouts of soldiers and Desert-folk were fading into the distance.

I raised my head and met the First Prophet’s gaze. “This is the beginning of our victory.” Tao had not died for nothing. My hand went to Kamose’s shoulder. “Behold, the first of the

Per-aa, as Lord Amun-Ra Himself decreed.”

Kamose rose and pulled me to my feet. Sunlight streamed into the sanctuary, a warm wind in its wake. The First Prophet and priests of Amun-Ra dropped to their knees before Kamose, Lord of the Two Lands—South and North to be reunited for generations to come.

* * *

* * *Karen L. Kobylarz first encountered ancient Egypt and Rome while watching

The Ten Commandments and

Cleopatra at the age of eight and has been a devotee ever since.

Her previous publications include the short stories “Expecting Miracles” (

Fables Webzine), “Cleopatra’s Needle” (

Paradox), and “Imperishable Stars” and “The Book of Thuti.” (

Leading Edge).

When she’s not exploring the mysteries of the Land of the Pharaohs, Ms. Kobylarz teaches third-grade transitional bilingual students at a local elementary school. She has B.A. in Elementary Education and an M.A. in Writing.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?[Karen L. Kobylarz] finds ideas for her stories from three sources. She remains an active student, attending as many classes, workshops, and lectures on ancient history as she can. Nonfiction books are also a source of inspiration as are educational programs on the National Geographic Channel, History, Discovery, etc. Sometimes a seemingly insignificant detail or a fleeting image raises the question: What if . . .?