The Watch-maker and the Pianist

by Natasha Pulley

Thaniel Steepleton suspected that his landlord could remember the future. He didn’t like to mention it; it was the year 1887, modern times in which superstition was being firmly elbowed out by steam engines and telephones, and Mr Mori was assuredly a man of the new mathematical age. Thaniel wasn’t sure that he understood subjects which did not involve clockwork and numbers. He certainly didn’t understand about Sunday mornings. Today, for example, he paused in the hallway as Thaniel was putting on his best jacket and hat, and said,

"Really, Mr Steepleton, I can’t think that your imaginary friend minds if you dress up or not. If he can see you all the time then it doesn’t stand to reason." He spoke with very slightly sharp consonants. He was from the Orient, though he dyed his hair light and in the watery March morning he had the insubstantial look of a newly spun ghost.

"Mori, God is not my imaginary friend, and I think He likes to see that occasionally we make an effort."

Mori frowned. They didn’t have the Bible in Japan and Mori’s response to it was usually one of such honest bewilderment that Thaniel quite enjoyed provoking him to talk about it. "And to listen to a man in a dress talk to you about flesh turning to grass? It just sounds very...sticky."

"It’s a robe, not a dress, and the grass is allegorical. Anyway, Mr Foddering promised to do the Song of Solomon today. You ought to come, it’s very beautiful."

"I can’t, I need to draw out some more watch-papers before Mrs. Grey comes." Mori refused to hand people back their pocket watches with no watch-paper in the lid. Watch-papers, Mori always said, were what told simple mechanics from real watch-makers. Lots of people could mend your clockwork, but only somebody who really cared about it would spend three hours inking an inch wide circle of paper under a microscope. Thaniel suspected that watch-papers had started out as only tiny business cards, discs of paper with the name and address of the watchmaker made to fit in the lid of a mended watch, but it seemed that clockwork attracted a lot of repressed artists and Thaniel’s friend Fred collected all his papers in a special book because he liked the patterns so much.

"You should be careful though, Mr. Steepleton. I don’t think it’s advisable to be too observant in your habits."

"Whyever not?"

"I’m only halfway through the Bible, but so far it seems to me that good things come to those who cheat and the righteous shalt be rewarded with a plague of boils. Boils are not hygienic, Mr. Steepleton, so if you wouldn’t mind pausing at a rigged race on your way home?"

"Any particular horse?"

"Ferryman’s Jack looks good, I think. And take an umbrella."

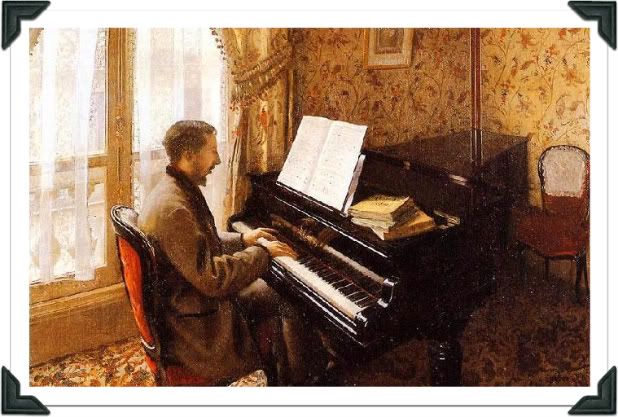

After it had poured with rain and after Ferryman’s Jack had won at sixty to one odds, Thaniel came home to piano music. He paused in the parlour doorway to listen. He knew a little about music- he sometimes paid the sixpence for the seats right at the back of the Royal Albert on a weekday- but he couldn’t play, unless you counted twinkle twinkle little star with one hand when he was bored. Of all the pianists he’d seen at the music hall, Mori was the most disaffected. He sat with his ankles crossed and a faintly disinterested look in his eyes while the voice of God sang in the harmony.

Thaniel clapped after a finished-sounding cadence. ‘"That’s brilliant. Where did you learn?"

Mori looked round. "Nowhere. I only learned from that one, I can’t play anything else."

"Who’s it by?"

"I’m not sure. English names all look the same." He leaned back on his small hands. He always had the terrible posture of a marionette with a missing string, but Thaniel thought it suited him. "And German ones."

"Mozart and Beethoven don’t sound the same."

"Nor do Katsumoto and Tokugawa, but I don’t expect you could spell them."

"I suppose," said Thaniel, who always thought he was being very reasonable and patient about Mori being Japanese until the situation was translated for him, whereupon he found that in fact he was being a prat. "Anyway, I was only interested. Is there any tea?"

"The kettle’s on."

Thaniel poured them both a cup and put the second on the piano while he sat down on the stool too with his back flat to Mori’s. "Play it again?"

Mori did as he was told and Thaniel felt the muscles in his back move as the music hummed again. He tilted his head back against Mori’s fair hair and sighed. He probably ought to have been guilty about feeling more peaceful and happy here with his godless housemate than he ever had in church, but he only felt peaceful and happy.

ENDYMION GRISZT

Playing TONIGHT at THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL

The Never-Before-Seen Opus. 12

(Tickets 2s, doors open at 8 o’ clock)

Thaniel peeled the newspaper off his face where his friend Fred Pike had thrust it in his enthusiasm. It was Monday morning at the office in Whitehall. They were both underclerks belonging loosely to the Home Secretary, so loosely that their department had been shunted into the building just opposite Horse Guards, a place which was always made to sound glamorous by army types but in fact involved only an awful lot of noise made by men in unfortunate hats.

"Can you take Annie? Only she always says I talk the whole way through. Besides, she’s a damnably pretty girl, Thaniel, and it would be nice to have a family connection, wouldn’t it?"

Thaniel took a breath, aware that pausing was probably just as bad as saying no in a situation involving Fred’s beloved sister. The trouble was twofold though. Firstly, he did have two shillings, but he had been hoping to spend them on the grapes from the grocer outside, since he quite wanted to convince Mori that people in England did not live solely off tea and sausages. Secondly, he took against Endymion Griszt because he knew that the man’s name was in fact Joseph Baker, and because neither Joseph nor Endymion were brilliant composers. His pieces tended to look a lot like paintings that had gone magnificently until the painter had sat on them by mistake. So he was surprised when he heard his voice say,

"Yes, I’d love to."

"Splendid," beamed Fred. Like Thaniel. he was a man of unremarkable looks and a side parting, but he had done exams in charm at Eton and the result was what Thaniel believed women liked to call Dashing. "Any sisters you’d like me to take out?"

"She lives in Kent with her husband and four children."

"And you’ve got no spare wheel in a tiresome menage a trios?"

Which was why Thaniel fled home the second the clock clicked around to six. "Mori!" he wailed.

"Tea," said Mori as he came through from the kitchen with two cups. The exact time at which Thaniel came hope depended completely on how much he was distracted by the beautiful cake shop on the corner of Trafalgar Square, but Mori had a knack for knowing.

"Fred wants me to take Annie to the music hall. Can you think of a way for me not to go that doesn’t involve my breaking a leg?"

Mori gave him the tea. "Usually you say you must visit your mother when he asks."

"But he was nearly bouncing. Look, I’d like to see you turn somebody down like that. Come on, you can be me. Thaniel, you’ll take Annie out to the music hall, won’t you?"

"Oh, yes. I was going with some friends anyway. You remember Frank Harris? We had to fetch him from the police station after he bit that woman’s ear off?"

Thaniel paused, unsettled. "You know the only flaw in that imitation was that it was much too clever for me."

"Well, I’m not under any obligation to Mr. Pike, so it was less stressful a moment."

"I suppose. Can I hide in your workshop?"

Mori considered. "No."

Thaniel went to skulk in the parlour instead and ducked under the piano when he heard Fred voice’s chattering by the garden gate, but it was no use. Mori let them in slightly before Fred knocked and, having the good luck to be foreign, was able to indulge in his habit of pretending he did not speak English.

"Sanieru-kun," he said to the piano.

"Why’s he under the...?"

"I dropped sixpence," Thaniel mumbled.

"Oh, I see. Niiice to meet you," Fred said slowly to Mori. "Do you speak eh-ny Eng-lish?"

"Iie, wakarimasen. Kimi no tomodachi wa boke da yo," Mori added to Thaniel.

"No, he isn’t. Don’t be rude," Thaniel muttered. He didn’t know the words but he had heard the tone before; it was the one Mori saved for when Thaniel tried to talk to him about the importance of cricket.

Fred looked impressed. "Gosh, Thaniel, do you speak Chinese?"

Thaniel smirked and looked down in time to see Mori’s slanted eyes narrow a little. Mori was particular about not being called Chinese, much in the way that Thaniel was eager not to be mistaken for Welsh. "I’ve sort of picked some up," he lied.

"Well, that’s splendid, isn’t it, Annie?" said Fred, consulting the light of his universe, a plain young woman with an interesting nose and a green shawl. "Thaniel here’s a brighter spark than I knew. Shall we go? Thaniel, you’ve met Annie before, but doesn’t she get better with age? Like good wine. Well, goodbye, Mr. Mori, nice to meet you I’m sure." He glanced at Thaniel. "Are you sure he’s a mister? He’s very...petite, I mean it probably bears checking."

"I’ll just get my coat," said Thaniel quickly, leaning inside past Mori. "Sorry," he whispered.

Mori didn’t seem to mind. "If they’re selling the music, could you buy it for me?" he asked instead. "I’ve put the money in your coat pocket."

"Yes, of course." Thaniel didn’t bother to count it. He knew it would be exactly the right amount.

They had a box to themselves, and despite Fred’s assertion that Thaniel was only there because he would not talk through the whole concert, Thaniel couldn’t see how doing so would have worried Annie, who had brought her knitting. It was excellent knitting; she was doing a pair of gloves with a pattern on the back, but the sound of quick knitter is a constant clicking and every now and then Thaniel saw the conductor looking puzzled and scanning the orchestra for anybody who might be fiddling with their clarinet keys or eating a boiled sweet. Thaniel didn’t mind. The concert was typical squashed-sounding Griszt with more maths than music and lots of bits that he had stolen from Mozart but not quite enough for anybody to sue him. Or at least it was until the last movement, when the orchestra left and Mr Griszt came out himself, a showman as usual with a red ribbon on his top hat, which he swept off to catch the rose a lady in the front row threw.

"Oh, he’s handsome, isn’t he?" Annie said cheerfully.

"No," said Thaniel. "He’s all shiny and unctuous and he talks like he’s swallowed a trifle."

Annie thought for a second. "Fruity?"

"Yes, that got away from me a bit," Thaniel admitted.

Down on the stage, Mr. Giszt sat down by the piano and pulled back his sleeves by a fastidious fraction of an inch before bringing his hands down on the keys. Thaniel expected more of his clever but painful discords, but though what he played was woven through with the clever things that had come before, it was quite different. It had a real harmony, and it sang up high and whispered in the left, and strains he remembered more and more often until he could have hummed the tune for a minute at once toward the middle.

"Do you recognise that?" he asked Annie.

"It says on the programme that he only finished writing it yesterday."

"Only I’d swear Mori’s been playing it all year. I must be hearing wrongly," he said, but he didn’t quite convince himself.

"Are you joking?" the man at the ticket office said when Thaniel asked him after the show. "Yesterday night. He finished the damn thing yesterday night, we thought we were going to have to cut that bit out but no, in he swings at half past ten with it written out in purple ink with crossings out and tea spilt on it and God knows what else. We only just managed to get the thing printed in time, if you want to buy-"

"Mr. Steepleton, Emily’s here, let’s all go for dinner. Come on. Emily, this is Mr. Steepleton, I can’t remember his first name-"

"Thaniel," said Thaniel, who was flustered to find himself presented with a very beautiful woman out apparently by herself.

"Delightful to meet you," said Emily, though in the way of very beautiful women she said the words with some irony.

Thaniel’s mind did a splendid impression of a blank piece of paper. She was wearing very plain clothes and no corset and his thoughts couldn’t seem to get past the curves under her blouse. Obviously all women had curves to varying degrees, except maybe Annie who had hiccups, but they weren’t so soft. "Um. Yes. You too."

"Excellent, we shall all get on stormingly," Annie said happily. "There’s a hotel over the street, let’s go there. Emmie, is George here?"

"George? Oh, no, I left him at home with the boys."

"Are you a suffragist?" Thaniel said, having at last managed to coax some thoughts into working again. They were doing so on the condition that restricted his gaze to her eyes and upward.

"No, I’m a woman with a brain and my husband is a milksop, which is why I married him. Annie, you really ought to do the same. Have you considered dear Mr. Steepleton here?"

Thaniel was aware that he ought to be offended, but he was too busy feeling pleased that she had remembered his name. He spent a very pleasant hour looking at her over a fine dinner at the hotel opposite, and having taken Annie home afterward to an exuberant Fred, he took a cab back to Filigree Street and wondered if it would be all right to ask the Home Secretary to make corsets illegal.

"Mori?" he said as he let himself into the house. "Mori, where are you? It was amazing, there was this beautiful women with no underwear on and she spoke to me."

"To tell you to stop looking at her?" Mori asked, rather flatly. He had just come out of his workshop and he was still wearing the gold glasses he used for navigating the finer parts of the clockwork. He took them off and hooked them over the top buttonhole of his waistcoat.

"Don’t tell me you don’t like beautiful women."

"I’m not very keen on any women at the moment. They’re walking flowers and I don’t want to waste my breath speaking to a chrysanthemum."

Thaniel laughed. "You know women are good for things other than talking."

"I do my own cooking."

"I mean-"

Mori sparkled at him mutedly and Thaniel flicked his arm with his fingertips.

"Don’t do that, I can never tell when you’re joking." He put his hands in his pockets to take out his gloves before he hung it up, and felt the cold coins Mori had left there early. "Oh, good grief, I forgot the music for you, I’ll go back and fetch it tomorrow. Though I’d swear it was that piece you’ve been playing since I came to live here."

Mori watched him with a seahorse stillness while he waited for him to come around to something sensible.

Thaniel sighed. "I’d better go to bed," he concluded.

FIRE AT MUSICIAN’S HOME

Police investigate absinthe accident.

Thaniel read the paper at his desk over his lunch the next day, which he was sharing with Fred because the Home Secretary was holding half a cabinet meeting in the canteen. Or at least, he tried to read the paper while Fred talked at him.

"...so I think we should all go out together, you and me and Annie. And then you and Annie will have a chance to talk some more, she said you were delightful yesterday to her friend Emily even though you had no warning she’d be there. Really very decent of you."

"Yes, it was lovely," Thaniel murmured as he turned the page. Unfortunately, Griszt himself was fine; on the bright side, the fire had eaten all of his manuscripts and the stack of unsold copies from the concert.

"Well, that’s settled, then."

"Damn," said Thaniel suddenly.

Fred looked up. "I’m sorry, old chap? I didn’t know you found my sister quite so repellent as all that."

"No—no. I mean—I was supposed to buy the music yesterday for Mori, but I forgot because of—er, Annie—and then I was supposed to go by and get it today but the musician’s house has burned down."

"How inconvenient," Fred said. "Anyway, I thought we should go somewhere nice and then-"

"Fred."

"Hm?"

"Can I just...look. Annie’s a delightful girl, but I’m in no financial situation to get married for at least a few years. I live with Mori because I can only afford half rent. I’d just like to be of better means before I start going about giving anybody ideas, all right?"

"Oh, of course. I was only joking before about a family connection, I just thought it would be jolly nice if we all knew each other and got along and so forth."

Thaniel deflated. "Right. Yes. Good."

* * *

"Well, I’m off the hook with Fred," Thaniel reported as he arrived back at number 27 Filigree Street. He hung up his coat and Mori gave him the cup of tea he’d been holding ready. "Thanks. Oh, did you see the paper? Griszt’s house burnt down, so I can’t get the music for you, but it’s all right, it was what you’ve been playing since January so you know it already. How do you, by the way? Griszt didn’t finish it until the day before yesterday, so unless you learned it from remembering the copy I was probably going to give you, months before I gave it to you, then I don’t see how and that’s completely silly. Actually, can I hear it again to check?"

Mori shook his head. "I’m sorry, Mr. Steepleton. I’ve completely forgotten how it goes."

Thaniel frowned. "What? But you knew the whole thing off by heart yesterday."

"Yes. I’m sorry. My memory seems to be arranged in an inconvenient fashion." He looked sad for a moment and then hid it neatly. "Mr. Evershot will be here in ten minutes and I haven’t finished his receipt, so you must excuse me."

He disappeared into his workshop, leaving Thaniel in the hallway with only the squeaking of the settling floorboards for company. Thaniel chewed the inside of his lip while he looked at the piano through the parlour door. "Completely silly," he mumbled. "Except...if you were remembering a possible future where I did remember to get the music, and it’s impossible now because his house burnt down with all the copies, then you’d forget what you’d learned from it when you did have the, I mean when you would have had..." He sipped his tea unhappily and went to sit down with Sherlock Holmes and the case of the apparently haunted house. "Or it sounded a bit the same as Griszt because Griszt pinches everything, I’m talking nonsense and you’re really forgetful. Except you’re not." He looked at Mori’s door. "Everything can be explained empirically and logically. The house isn’t haunted, it’s just troubled by an irate snake. Well, bully for you, Mr. Holmes. I’d like to see you say that here."

Mori leaned through with his accounts book open in his small hands. "Mr. Steepleton, I’m sure I read that your first imaginary friend would be upset if you started talking to other imaginary people too."

Thaniel smiled. "I don’t think Sherlock Holmes counts."

"Are you sure?" he said seriously.

"Fairly."

"Well, good. I wouldn’t want you to be turned into a pillar of salt in the middle of our parlour. The maid’s got flu, she won’t be in for a week."

"No, she hasn’t, she was in this morning, singing. About...oranges and psychopaths, or something," Thaniel finished vaguely. He didn’t come from a musical family and so nursery rhymes had a way of confusing him now. It was no wonder that all the children on the street were so strange and unusual, he thought, if people kept telling them things like that. He could not think that the way to produce a sensible and well-balanced adult was to insist that bells talked about fruit in their off hours.

"Oh, I must have got confused." He drifted back into the workshop and didn’t come out when there was a knock on the front door.

"Mori? Isn’t that your Mr. Evershot? No, all right, I’ll get up, don’t worry, I’ve only been at work since seven o’ clock this morning..." Thaniel opened the door. It was not Mr Evershot. "Can I help?"

"Um, yes, sir, I’m Felicity Keane’s brother."

"Felicity...oh, the maid. Yes. Is she all right?"

"That’s the thing, sir. It’s nothing serious, but the doctor says she’s got a touch of the influenza going about and she wanted me to make sure it would be all right with you if she doesn’t come in til next week. I can fill in for her if you really need?"

"No, that’s all right, Mr. Keane. Thank you for telling me. I hope she’s better soon."

"Thanks very much, Mr. Steepleton."

Thaniel shut the door. "The maid won’t be in for a week," he said to the workshop door. "She’s got flu."

Image by Gustave Caillebotte

* * *

Natasha Pulley says: I have just finished university at Oxford, where I read English Literature and was usually bewildered. Now I live in China, where I'm also bewildered. I teach English in Han Dan and although it must be at least the size of London, I've seen no other westerners here- Chinese people keep stopping me in the street to take my photograph because I look so unusual to them. Accordingly, very few people speak English here, so I read a lot in my spare time, mostly Terry Pratchett and Arthur C. Clarke. At home I have a peculiar brother, who I'm looking to trade in for a cat.

What do you think is the most important part of a historical fiction story?

The balance between history and fiction. History is always much funnier and more idiosyncratic than I think it is and I would never have guessed half the things I found out from even just a bit of research. At the same time, I think that it's important not to fret about overly specific details, such as what manner of guttering was used on terraced London houses post-1850, or the precise measurements and architectural features of the average garden shed. It's fiction. Make it up.

2 comments:

Brilliantly engaging.

I'm currently reading the novel that this was spun into. Actually, I've gotten so into the story already that I googled Natasha Pulley and found an interesting article she wrote about Sherlock Holmes for The Bubble and this short story. I'm enjoying the vaguely fan fic feel of this. Ms. Pulley, you can count me a fan.

Post a Comment