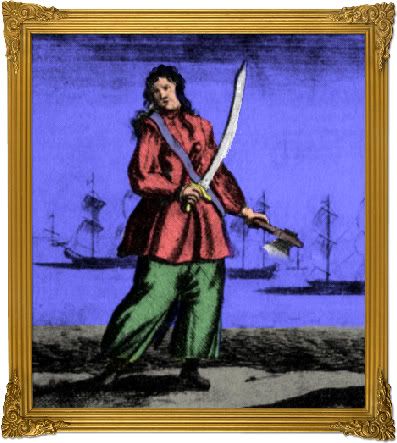

Shaitan's Daughter

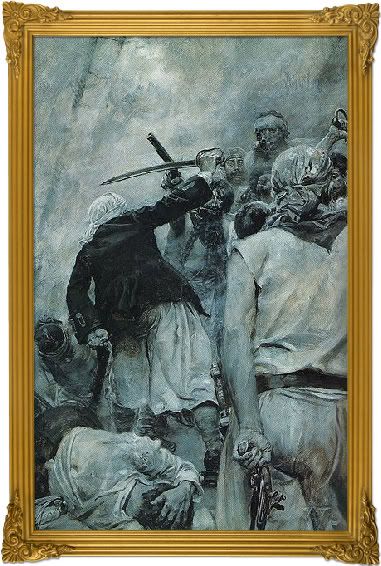

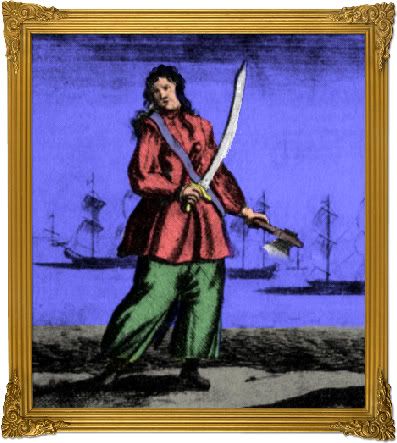

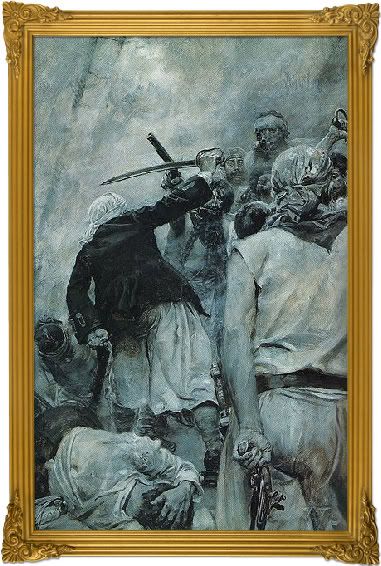

by Barbara Davies “Shaitan's Daughter” they called her, and she certainly looked the part. Dealing out death with her hawk-headed scimitar, a feral smile on her lips, while the breeze off the ocean tried to snatch off her cap.

* * *No smoke rose from the watchtower on the cliffs to the south, and no gunshot or blare of a conch shell sounded the alarm. Perhaps the watchman had been as taken unawares as everyone in our village. It was midmorning, and slavers usually come in the early hours, kicking down doors and dragging their victims naked and drowsy from their beds.

I was down on the jetty, earning a few extra

reales by helping load the weekly shipment onto Tito's boat: alum, agates, jasper, and gold from the mine a little way inland, and salt from the salt marshes. It was hot work, and I had straightened to take a breath when I saw them—three low slung, narrow ships, a galley accompanied by two galliots, gliding across the turquoise water of the bay towards us, as sleek and deadly as sharks.

The sight of the colourfully turbaned figures, armed with scimitars and arquebuses, silently crowding the prows struck me dumb, but my expression alerted Tito.

He swung round in horror. "Turks!"

Some of his crew scrambled to loose the mooring ropes—as if the lumbering boat had any chance of setting sail before the raiders reached us!

Banks of oars rose as the approaching ships coasted the remaining distance. By the time the galliots' keels crunched on the sand and the galley drew alongside the jetty, I was running, my thoughts on one thing:

Damita!

At this hour, my little sister should be helping with the laundry.

Past the racks of drying sardines and the fishing nets strung up to dry I darted. In spite of the sun’s heat, the shouts of “Allah” from behind as the corsairs attacked Tito’s men chilled me to the bone. I glanced back. Any hope I might have had that they would be content with his cargo was dashed as they split into two groups.

Something odd about the figure directing the raiders’ movements snagged my attention. From the splendour of his clothes and his commanding stance he was their captain. But he was beardless, and wore a modest cap rather than a turban. I had no time to consider his appearance further. With a roar, the Turks started up the beach after me.

My panting and the thud of my running feet made heads turn as I reached the outskirts of our village.

An old fisherman half rose from the upturned barrel on which he had been sitting, whittling a piece of driftwood. "What—"

"Turks!" I gasped. The men with him exchanged shocked glances and reached for whatever was close to hand—an oar, a gaff, anything that might serve as a weapon. I shook my head and thrust a fist into my aching side. "Too many. Hide yourselves."

They hesitated for only a moment, then scattered, shouting to everyone within earshot to run for the caves. I headed for the laundry troughs, my panic easing as I saw my sister helping old Albertine wring water from a sheet.

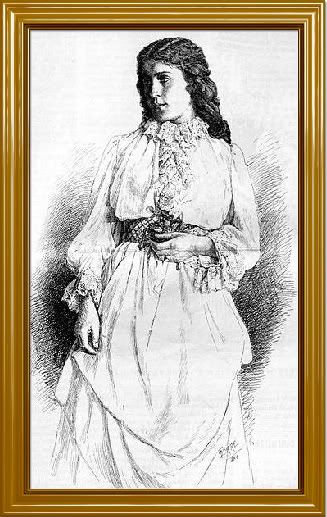

She pushed a strand of hair back from her face and smiled at me. "Adriano!" Her smile faltered as the alarm bell in the village square started to clang. "What’s wrong?"

"Slavers."

The old woman dropped her laundry and ran off. Damita gave her an astonished glance.

"We have to get out of here, now," I told my sister.

"But what about...."

Screams mingled with shouts of “Allah”. Black smoke curled upwards from the beach.

"We must get to the caves." I grabbed her by the arm. "Hurry."

But her eyes were wide, her attention on something over my shoulder. I turned and saw the first of the corsairs, a huge Moor in a red turban, his sleeves rolled up to reveal massive biceps. He grinned and made a show of twirling his scimitar.

Damita let out a piercing scream, tore herself free, and ran.

"Not that way!" I shouted as, out of instinct, she headed for the safety of our house.

More of the raiders, many with moustaches rather than full beards, were on the heels of the Moor. I set off after my sister.

Damita cut left at Albertine's house, then right. Panic drove her steps and deafened her to my shouts, but I was gaining on her with every stride. Then a corsair in a blue turban stepped into the alleyway directly ahead of her, and she halted and looked round wildly.

"Come here, my pretty," called the corsair in bad Spanish.

I pounded up beside her and put myself between them. Her tears put me in a rage and I turned on him and shouted, "I won’t let you take her."

The clangs of the alarm bell stopped abruptly, replaced by screams and triumphant bellows.

"How are you going to stop me, boy?" His teeth gleamed behind his bushy beard. "With your fist?"

I produced the gutting knife from my belt.

"Don’t be a fool. If you can find someone to ransom you..."

Who would pay for the release of a poor fisherman and his sister? I wrapped an arm around Damita, and pressed the knife to her throat. She squeaked in surprise. "I’m sorry," I whispered. "I’ll make it quick. You’ll see mother and father very soon."

"You would kill your sister?" asked the corsair, astonished.

Better that than let her suffer at the hands of the Turks. My hand was shaking but I should still be able to make the slice across her throat swift and sure—

"Stay your hand!" A woman’s voice with the ring of command to it made my hand freeze. I looked round. No wonder the corsair captain’s appearance had struck me as odd. She wore a man’s knee length tunic and trousers, her only concession to her sex being the cap covering her dark brown hair.

"Release her and she goes free," she said in perfect Castilian.

I gaped at her.

"It’s galley slaves I’m after, not concubines or house servants. Come with me freely and I will let your sister go."

The man in the blue turban threw her an indignant glance. "But,

re'is!"

Her raised hand stopped him. His jaw worked, then he gave her a sullen nod and stalked off.

"Well?"

I could feel my sister’s body trembling. "How do I know I can trust you?"

"I give you my word, by Allah."

I spat on the ground. "The word of a corsair."

She studied me. "And of a sister who loved her brother."

"Adriano!" whispered Damita, a pleading note in her voice. My will to kill her drained away and the knife dropped from my slack fingers with a thud. I let her go and she turned and regarded me in confusion.

The corsair captain nodded. "Your name?"

"Adriano."

"Say your goodbyes to your brother, girl, and run for the caves." She saw my puzzlement and shrugged. "There are always caves."

Damita remained frozen.

"Go!" The woman’s bellow broke my sister’s paralysis.

Eyes brimming, Damita hugged me and ran. I watched her disappear into the distance—she didn’t look back.

The woman motioned me to join her. We walked back through the now empty village towards the beach, where the corsairs were busy loading cargo and captives onto their ships.

My heart thumped as the magnitude of what I had done came crashing home. But my sister was safe. A touch of bravado came over me. "I told you my name. What’s yours?"

Her lips twisted, as if at some private joke. "They call me Shaitan’s Daughter."

"And are you?"

We mounted the jetty and walked towards the galley. "You decide."

* * *

* * *"Welcome aboard the Ruby Scimitar," said the grizzled old Spaniard whose rowing bench I was to share. He held out a calloused hand, chain clinking. "I’m Alvaro."

I waited for a Turk to finish attaching my wrist to the heavy oar and my ankle to a chain that ran the length of the bench, before taking his hand. "Adriano."

He jerked his thumb at the two men sitting on his other side. "Miguel. Giacomo."

They peered at me and nodded a greeting.

Before I could ask questions, the mooring ropes thudded onto the decking, and there came a series of whistles. A Turk at the boat’s stern began to pound a drum. My bench mates reached for the oar and the chain around my wrist yanked my hand with it. It took me a moment to pick up the rhythm.

Alvaro gave me an approving nod. "You’ll get used to it."

As the galley reversed out into the clear waters of the bay, Turks gathered round the prows of the two galliots, ready to shove off and follow us. The smoke from Tito’s burning boat receded into the distance, taking the coastline and all I held dear with it.

A lump formed in my throat.

I’ll return, Damita. By the Holy Virgin, I promise. I had seen no sign of my cousin among the captured men. He would look after my sister.

At least she’s alive."Cheer up," said Alvaro, catching my expression. "This ship’s not as bad as some. You can thank our

re’is for that." He jerked his head towards the corsair captain, who was standing on the poop deck, staring out over the ranks of rowers.

I grunted my disbelief. The men on the bench in front wore ragged linen breeches that covered their privates and little else. Their sunburned backs were scarred with lash marks, courtesy no doubt of the overseer prowling up and down the central catwalk, a tar-dipped, knotted rope’s end dangling from one fist.

"You’ll see," Alvaro went on. "She may be the bitch from hell, but she’s not a sadist."

As if the woman knew we were talking about her, her brown eyes rested on us, then her helmsman distracted her with a question and she turned away.

Pungent, sweet-scented smoke drifted over from part of the stern that had been enclosed to make the only shelter on the vessel. Moustachioed, armed fighting men lounged there, talking and smoking pipes.

Alvaro caught my glance. "Janissaries. That’s opium you can smell."

"It’s all right for some," grumbled Giacomo.

As we rowed, we exchanged our stories. Giacomo came from Lisbon and spoke Spanish with a thick accent. He was an arquebusier with the Portuguese infantry, on leave when the corsairs took him seven months ago. It had been four years since Miguel had been snatched; he was tending his goats on a hillside near Valencia. As for Alvaro, six years had passed since his fishing boat was attacked further up the coast from my village. All were younger than they appeared, their hair prematurely grey, lips chapped, and with deep creases around the eyes from squinting against the sunlight reflected off the water. I wondered how long it would take me to acquire the same characteristics, including the stench of stale sweat.

Alvaro briefed me on the galley’s command structure. The

re’is had overall charge, but the fighting men answered to their

aga.

"Pace yourself," he advised. "It’s a long pull to Algiers."

"Is that what happened to my predecessor? They didn’t pace themselves?" There had been empty places on several of the rowing benches, now filled by men from my village. "I wondered if it might be plague."

"Not this time," said Alvaro. "The

re’is works us hard. Some

galeottis just aren’t up to it. Pedro’s heart burst in his chest."

At the mention of their former bench mate, Miguel crossed himself and muttered, "Should have given him a proper Christian burial. Heathens!"

"You there, save your breath for rowing!" called the overseer, his glare fierce. After that we rowed in silence.

Already I could feel blisters starting to form on my palms and my back was aching, but the oar’s demands were relentless. I tried to distract myself by following the progress of the

re’is around the galley. I was not the only one watching her; there was something about her that drew the eye. Taken separately, her features weren’t anything out of the ordinary: olive skin, a piercing gaze, a rather hawkish nose. But taken as a whole....

"Fascinating, isn’t she?" said Alvaro, when the overseer was safely occupied at the other end of the walkway. "You’ll probably dream about her." He grinned. "The rest of us do."

"But a woman as captain! And she speaks Castilian. Is she a renegade turned Turk?"

"Her name’s Muhya, but you must address her by her title. She’s a Mudéjar from al Andalus." Alvaro threw me a significant glance. "Her family were forced to flee to the Maghreb."

I grimaced, knowing how hard life was for Muslims under King Charles. "Little enough reason to love Christians, then."

He grunted agreement.

"But she wears no

yashmak," I persisted.

"Likes her victims to see who killed them?" guessed Giacomo.

Miguel shuddered. "Unnatural creature."

"What turned her into a slaver?"

"God knows." Alvaro was rowing one-handed so he could scratch a fleabite. "They say she sailed with Barbarossa for a while, learning the ropes. And that he had a soft spot for her."

"More like a hard one!" Giacomo's grin was lascivious, and Miguel threw him a disapproving glance.

Alvaro ignored them both. "Then she struck out on her own."

Something cool feathered the side of my neck. I glanced round.

"Praise God!" said Alvaro. "A breeze!"

Muhya's second-in-command let out a shout and sailors unfurled the sails. Shortly after, the flap of canvas, creak of block and rigging, and the cries of the seabirds wheeling above our masts replaced the splash of the oars and the relentless pounding of the drum.

As we sat, recovering, a Turk came round handing out hard black biscuits and let us gulp our fill from a skin of watered vinegar. I grimaced and thought longingly of sardines cooked with oil and garlic.

"I thought you said The Ruby Scimitar is better than some!"

Alvaro winked and bit into his biscuit. "It is."

* * *I had been hoping for respite in Algiers, but it was not to be. A Turk in a purple kaftan was standing on the quay, and Muhya left her men unloading goods and captives, the latter bound for the slave market, and went to meet him. The pair walked away, deep in conversation, and when she returned, her eyes had a distant look, her jaw a determined jut.

Her junior

re’is took some convincing before they nodded and went back to their galliots. She beckoned her second-in-command and the janissaries’

aga to her. Their voices drifted towards us from the poop deck, but they were speaking too fast and in the

lingua franca I had yet to pick up. From the expressions and gestures, her proposal was unpopular.

"What’s happening?" I asked Alvaro, who was listening intently.

"Hush." After a moment he breathed, "Holy Mother of God! She must have a death wish."

"What is it?" asked Miguel.

"A Hospitaller ship’s been sighted off Tunis. She’s going after it."

Miguel’s face paled.

"

Merda!" Giacomo crossed himself. "Everyone knows they’re like scorpions—best avoided."

"What are they doing this far west?" I wondered.

Alvaro shrugged. "Whatever the reason, they’re within our range."

The

aga threw up his hands and let them drop, then stalked off to talk to his janissaries.

I scratched my jaw. "They don’t look happy."

Alvaro glanced at me. "Would you? They were expecting feasting in celebration of a prosperous voyage. Instead we’re putting to sea again."

He was right. A turn of the hourglass later, we were rowing out of Algiers” harbour, water barrels restocked, banner flying.

There were several fresh faces this voyage, replacements for those corsairs who had opted to stay in Algiers.

"Watch out for that one," muttered Alvaro, eyeing a bald corsair with a ring in his right ear and a badly scarred face. He was called Omer, and the way he liked to puff out his chest and strut reminded me of a rooster.

Alvaro’s instincts were proved right when Omer snatched the whip out of the overseer’s hand, and administered a flogging to a slave himself. Only when the man lay bloody and unconscious over his oar did Omer stop, a satisfied gleam in his eyes.

Muhya had watched the proceedings with a frown, and I thought that, had the slave been anyone but Joseph, who according to Alvaro had once been a Hospitaller knight, she would have intervened.

"Why does she hate the Knights of St. John so much?"

Alvaro sighed. "Few Muslims have cause to love them."

A breeze sprang up, and Muhya ordered the sails raised. The drum fell silent and we shipped our oars and dozed, ate, or clambered over one another, chains clanking, to the opening at the hull side of the bench to relieve ourselves.

The wind carried the scent of heat, dust, and the faintest hint of jasmine—the Maghreb was not far to our south—and a longing for home nearly overwhelmed me. Night fell, and the stars winked down as we snatched a few precious minutes of sleep. But all too soon the breeze dropped and the whistle blasts I had grown to hate woke us, followed by the beat of the drum.

We took up our oars once more.

All night we rowed, at the fastest cruising speed a

galeotto can sustain without collapsing. The coming of dawn revealed haggard faces among crew and slaves alike; only the janissaries looked well rested.

"Why doesn’t she put in to the coast somewhere and let us sleep?" asked Miguel.

Giacomo rolled his eyes. "Isn’t it obvious? She’s afraid our prey will slip away before we get there."

We rowed for two more hours and were coming up on Tunis when the lookout’s cry went up. Muhya shaded her eyes, then her face split into a grin. We glanced at one another in apprehension.

"God save us!" said Miguel.

The galliots drew level, their captains exchanging shouts with Muhya across the water. We were sailing blade to blade, and I feared that at any moment an oar would become entangled, but the helmsman’s skill kept us clear. Above the sound of our drums, I heard the beat of the enemy’s and the blare of trumpets.

Then our forward guns opened fire. Moment later came the reply, as a shot screamed overhead and splashed into the ocean. On the catwalk, the overseer clapped a hand to his shoulder with a look of pained surprise. When he studied his bloody hand, I saw he had been shot. Another Turk ran to relieve him.

A crossbow bolt thudded into the hull beside Giacomo, and the ball from an arquebus chipped splinters from the wood between my hands. I cursed and let go of the oar.

The new overseer lashed out at me with his whip. "Keep rowing, dog!"

Back stinging, I grabbed the oar once more.

The galliots dropped astern, then came the order for our side of the galley to ship oars. The boat began to turn, and I caught my first glimpse of our prey.

"Mother of God!" breathed Miguel.

The Hospitaller galley was almost on top of us, and she was a sight to chill the blood. Larger and more imposing than the Ruby Scimitar, she was painted a brilliant scarlet, and the triangles of her sails were red and white, emblazoned with the eight-pointed, black cross of the Order of St John. Sunlight glinted off armour and burnished mail as knights and men-at-arms milled on her deck and peered at us over the railing.

There was a cracking and snapping of wood. Splinters rained down on us and a judder went through the galley. Her speed faltered before picking up again.

"We’ve crippled their oars!" shouted Giacomo.

We came about and started rowing once more, the galliots resuming their position on either side, then our forward guns opened up again. The crash of a mast toppling was followed by agonised screams and shouts of "For Our Lady and St. John!"

The drumbeat rose to a furious tempo and the overseer began to run up and down, lashing out indiscriminately.

"Ramming speed!" said Alvaro. "Brace yourselves, lads."

His words were lost in the great crash as the galley’s metal-tipped spur hit home. If we hadn’t been chained to our bench, the impact would have sent us flying. As it was, the oar winded us, and we lay across it, gasping.

A great roar went up and I raised myself in time to see the janissaries charging across the ram onto the impaled Hospitaller ship. Muhya was with them.

Crossbow bolts and arquebus balls rained down on us as I watched the blur of colour and movement that was Muhya slashing her way towards the enemy’s poop deck where the enemy captain was regarding the melee below him with a frown.

The clash of blades and crack of arquebuses mixed with roars and screams, and the acrid stink of gunpowder grew stronger. Soon a pall of smoke was obscuring the view and when next I saw the

re’is, she was engaging the enemy captain. Unlike him, she wore no armour for protection, but his was bulky and hampered him. They appeared equally matched, but what did I know?

Then the smoke obscured the two fighting figures once more. Moments later, a severed head flew, bounced off the rail, and splashed into the sea. My heart pounded, but before I could voice my fears, the smoke had cleared again.

Muhya stood alone on the poop deck, bloody scimitar raised in triumph. At the sight, the Turks let out a great roar and the Knights of St. John groaned.

* * *

* * *Both sides of the Ruby Scimitar were packed with slaves jubilant at being freed from the Hospitallers’ rowing benches, some still sobbing with relief. They leaned on the parapet or sprawled on the planking jutting out over the oars, rubbing shoulders with tired corsairs and sailors. The janissaries had retired to their shelter and once more the scent of opium wafted to our nostrils.

The Hospitaller captain’s comfortable chair had been installed on the poop deck beneath a hastily erected awning. On it sat a grey-haired woman in expensive silks. For all she was clearly exhausted, her back was straight, her manner haughty. Muhya and her men treated the woman as solicitously as if she had been their own mother. She was the aunt of the wife of the pasha of Algiers, apparently. The Hospitallers had intercepted the ship bringing her from Athens, and demanded a ransom. The pasha would reward her rescuers handsomely.

On the

re’is’s orders, every last one of the Knights of St John had been slain. Our final sight of their galley had been of her red-painted hull, now canting at a precarious angle and gaping with holes from cannon shot and ram strikes, sinking beneath the waves. Muhya’s lack of mercy shocked me. It had also upset some of her men, though for different reasons.

"Omer thinks it’s all very well rescuing the aunt, but the

re’is should have ransomed the knights and their galley," reported Alvaro. His eyes were fixed on the bald corsair with the scarred face, who was talking to his friends not far from our rowing bench. "They’d have fetched a tidy sum, Omer says. She’s cheated them out of their share."

"He’s jealous," said Giacomo.

"No man likes having to answer to a woman," said Alvaro.

I wondered if Muhya was unaware of Omar’s resentment or didn’t care. But if he was disgruntled, the freed slaves adored her. Heads turned and respectful greetings followed her as she made her way round the galley, inspecting the damage done to both vessel and occupants. One Muslim even kissed the hem of Muhya’s trousers and called her his saviour.

"A pity there’s no one like her around to save

us!" muttered Giacomo.

Our losses had been light—three corsairs dead and few serious injuries. As the doctor treated the wounded, Muhya’s clerk took notes of their injuries. The families of those corsairs who had died would be sent compensation. No such consideration applied to us. I watched a Turk tie a length of chain round a dead

galeotto's ankles and pitch him overboard. It was Joseph, and as his corpse splashed into the deeps I said a silent prayer that he had found relief from his torment.

Depression settled over us like a pall and we rowed in silence. The sun beat down on our heads and backs, until the helmsman changed course to put us closer in to the Maghreb—Muhya wanted to put ashore, so the Muslim dead could receive proper burial. A welcome breeze picked up.

The

re’is paused on the central catwalk to talk to a corsair who had lost two fingers. We hoped she would move on soon, for her presence made the overseer overeager.

"Uh oh." Alvaro spied Omer at the same time I did. An air of frustration and banked anger cloaked the corsair as he made his way towards Muhya.

Her head came up as he drew near. "Omer."

"

Re'is."

They were so close I could hear their conversation clearly, but lack of

lingua franca hampered my understanding. Omer's meaning was plain, however. He bunched one hand into a fist and smacked it into his palm for emphasis. Muhya’s lips tightened and her reply was terse. He bowed his head, but I could see he was far from satisfied. And as he turned away he caught sight of me watching him.

"Look out," warned Alvaro, as Omer’s face suffused with anger.

Too late. The corsair had snatched the whip from the overseer and the rope’s tip caught my left earlobe and tore it off. Pain lanced through me, and I felt the warm gush of blood down my neck. I raised my arm and ducked, fearful the next blow was going to take out my eye, but the attack stopped as suddenly as it had begun.

I blinked and saw a thwarted Omer glaring at Muhya, who had taken possession of the whip. She returned it to the overseer and walked away. Omer scowled at her back, his face growing redder by the second. Then he started after her along the catwalk, his hand going to his sword hilt.

"

Re'is, look out!" I shouted.

But she was already turning, her own scimitar sweeping up and out in a great arc. Blood sprayed over the rowing benches, and something landed at my feet with a thud. The severed hand was still clutching the scimitar. I gaped at it then sought its owner. Omer was kneeling at Muhya’s feet, his face ashen, his expression one of disbelief, trying to staunch his bleeding wrist with one hand.

Silence had fallen, broken only by the slap of waves against our keel and the sound of a man being sick. All eyes were on Muhya. Her expression was glacial as she regarded Omer. She hefted her still dripping sword and for a moment I thought she was going to lop off his head. Instead, she gestured, scattering yet more scarlet droplets over the decking, and said something. I thought I heard the word for “fire”. Moments later, a sailor brought her a burning torch.

As Muhya herself cauterised his wrist, Omer let out a terrible scream. I can still hear it in my nightmares sometimes. Mercifully, unconsciousness cut short his suffering. His friends carried him to a corner of the poop deck and erected a makeshift awning over him. Normal activity resumed, but what had been a joyous atmosphere was now muted. Only Muhya was unperturbed by what had happened. But she seemed deep in thought.

"She’s planning something," said Alvaro.

But what she had in mind, I could never have imagined.

* * *My bench mates looked on in dismay as two Turks unshackled me, dragged me to the poop deck, and forced me to my knees in front of the

re’is. She was cleaning her sword with a rag; its hilt was shaped like a hawk’s head. A few feet from her, the pasha’s wife’s aunt dozed in her chair.

Muhya glanced up, grunted, and resumed her task. When the blade’s cleanliness satisfied her, she sheathed it and turned her attention to me.

"So," she said in Castilian. "The man who would save his sister’s life now seeks to save mine."

Her expression was unreadable. I glanced towards the awning, where the unconscious Omer lay, then ducked my head, uncertain how to respond.

"What made you think I needed your help, slave?"

Deep down, I had been hoping, almost expecting her to thank me. My heart pounded.

"Is it that I’m a woman?" she went on, her voice gaining in volume. "Weak and feeble and unable to defend myself?"

Several corsairs exchanged baffled glances. After a moment, one began to provide a low-voiced translation of Muhya’s words.

"No,

re’is." But there was truth in her words, and I felt my cheeks redden. "Your back was turned when he drew his sword. It seemed a cowardly act, treacherous."

She stood up and took a menacing step towards me. "You thought Allah would not keep me from harm?"

It dawned on me that I was in serious trouble. I blinked the sweat from my eyes. "Yes,

re’is. I mean no. I thought—"

She cut me off with a gesture. "Slaves don’t think. Slaves obey."

That drew a laugh from the listening corsairs and she smiled at them before continuing.

"I don’t like troublemakers." She drew her sword and pointed it at me. "Any man who causes trouble, be he a member of my crew—" she gestured with her free hand towards the unconscious Omer, "--or a slave, I punish."

A fit of trembling overtook me. How could I have so badly misjudged her? She had been named Shaitan’s Daughter for a reason. And I had seen from the Hospitallers how ruthless she could be.

But she didn’t cut me. Instead, she issued a crisp order and I found myself being carried over to the parapet. A roar of approval went up, and the aunt woke from her doze with a start.

As they dangled me over the side by my ankles, the waves rushing beneath my head terrified me. "Have mercy,

re’is!"

I tried to convince myself that they would soon pull me back up and return me to my bench. She was merely playing with me as a cat plays with a mouse. But the minutes passed and the blood rushed to my head. Planking brushed my reaching fingertips. I tried to grab hold of it but could get no purchase. Then a face peered down at me over the rail.

Even upside down I recognised Muhya. For a moment I felt hopeful. Her brown eyes were alight, her lips curved in amusement.

"I hope you can swim, Adriano," she said.

Then the grip on my ankles vanished and I plummeted into the sea.

* * *

* * *For a long time after, I hated her. I had tried to help her, and she had made me shark bait. It was fortunate we were heading shoreward when they pitched me overboard. Fortunate that, unlike many of my countrymen, I was a strong swimmer. Even so, we were far enough from land that it tested me to my limits.

By the time I dragged myself up onto the beach and retched up a lungful of seawater, I was close to exhaustion. A fisherman found me, sprawled as one dead, and carried me home. There, a fever ravaged me—my torn ear lobe had become infected—but I recovered, though it left me weak and shaky.

Though I was an escaped slave in hostile territory, I found kindness as I slowly made my way west, bypassing Algiers and other corsair haunts for fear of recapture. Common folk took me in and fed, clothed, and hid me. I was never far from exhaustion, and several times was on the verge of giving up, but my hatred for Muhya and a longing to be reunited with my sister drove me on.

Eventually, I crossed back into Christian territory and was able to relax my vigilance. In the Portuguese-run port of Ceuta, where on a clear day you can see the Spanish mountains, I found a sea captain preparing to set sail across the straits. He let me work my passage and two weeks later, footsore and weary almost to death, I arrived home.

The first thing I did was to drop to my knees and kiss the sand. The second was to wrap my arms around Damita, for to my joy and intense relief my sister was safe and well.

It had been a long, nerve-shredding journey, however, and now reaction set in. The slightest thing—the cry of a gull, the sight of my sister sitting quietly sewing—could reduce me to weeping. I could not explain why. Damita quickly grew accustomed to my fits, merely rolling her eyes and telling astonished onlookers to ignore me.

I tried to pick up the threads of my old life, but some of the villagers couldn’t overcome their resentment that it had been I who had returned and not their son or brother. I caught myself repeatedly scanning the horizon and the slightest sound made me jump. Every night I dreamt I was at my oar again. And every morning I woke and felt relief that the drum beat was only the pounding of my heart.

In the end I moved Damita and myself to a village further inland that had never been the target of corsairs. There I found work on a farm, and the simple labour helped rebuild body and mind.

One day, after I had recounted my bitter tale to Lucita, the pretty young woman who would become my wife, she asked me a question that turned everything on its head.

"That captain hoped you could swim," she said, as we lay in each other’s arms. "Did she mean it?"

I raised myself up on one elbow. "Of course not! She was taunting me."

"Then you are lucky she didn’t tie a chain round your ankles, Adriano," she said with a yawn. "You’d have sunk like a stone."

Lucita's observation triggered doubt where there had been certainty. Gradually it dawned on me: was it possible that I had misunderstood Muhya’s intentions? That for all this time I had got it wrong? Listeners to my tale often remarked that I was fortunate.

Galeotti usually died at their oars. If I had not escaped, I would probably have died there too. But escape I did, unshackled, and within reach of land.

Could it be true that Muhya had made it look like a punishment but it was in fact a reward? She had risked my life, for she had no way of knowing whether I could swim or if a shark might not take me before I reached land. But how else could she set me free without losing face in front of her men?

I will never know for certain. Muhya de Belvis, for that was her name I later learned, died a few years after my escape. At the hands of Hospitaller knights—apt, considering her background and bloody exploits.

She was only ten when the galleys of the Knights of St. John came raiding along the coast and scooped up her brother. Six years she searched for him, without success. What she eventually discovered broke her parents’ heart and made her vow revenge. For her brother was a galley slave like me. But unlike me, he died a wretched death at his oar.

My dreams of the rowing benches have faded and grow less frequent by the year, but I don’t think they will ever vanish entirely. I now own the farm I used to labour on and Damita and her husband live close by. Though my scarred ear twinges from time to time, I’m hale and prosperous enough that Lucita and Nerea, our daughter, need never lack for anything. Nerea is the same age that Muhya was when our paths crossed. I can’t help but contrast their lives.

People have tired of my tale of the female corsair, so these days I rarely tell it. But if a stranger asks, I make sure to inform him of one thing: “Shaitan’s Daughter” they called her, but she was an angel to me.

* * * Barbara Davies is a freelance writer and reviewer and lives in the English Cotswolds.

Her short fiction has appeared in various genre magazines, ezines, and anthologies, including Marion Zimmer Bradley's Fantasy Magazine, The Lorelei Signal, Khimairal Ink, Byzarium, Neo Opsis and Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine.

Her two lesbian historical novels,

Christie and the Hellcat and

Rebeccah and the Highwayman, are available from Bedazzled Ink, as well as a collection of her short specfic:

Into the Yellow and Other Stories.

Barbara's website is: http://www.barbaradavies.co.uk

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?To someone more used to writing science fiction and fantasy, the big attraction of historical fiction is that I don't have to make up the setting. It's there already, in all its grime and glory - all I have to do is find it. Cue lots of research, but I have always enjoyed that. Besides coming in handy for answering quiz questions

, researching a particular period of history always throws up unexpected and fascinating nuggets of information that I can use to enrich my characters and plot too.