The Letter of Marque

by Catherine Lundoff Celeste Adele Girard laughed, fluttering her fan just below her topaz eyes. The gesture was enough to make her audience, old rakes and young chevaliers alike, to vie against each other even harder to make her laugh again. But Celeste was becoming distracted. Her gaze turned as often on the ballroom door as it did to her admirers.

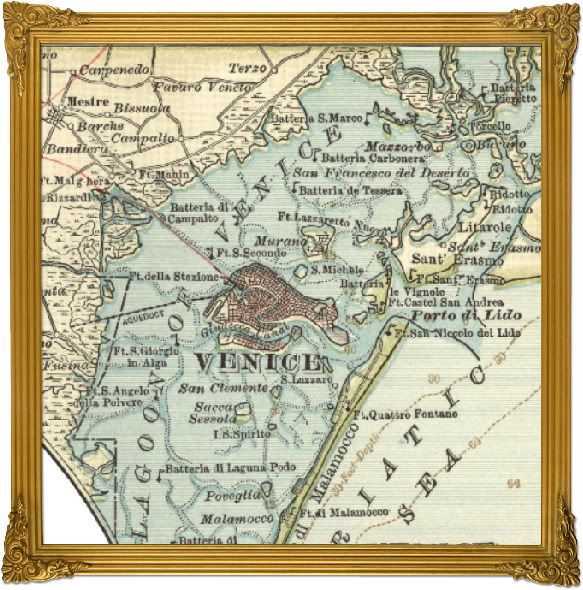

A liveried footman announced each new guest as they arrived, bowing them into the Governor’s ballroom as if it were Versailles itself. Celeste smothered a sigh at the memory of her last vision of her beloved France. Oh, to leave this benighted island, hot, dull and filled with boorish Englishmen!

Sternly, she reminded herself that the King had promised to make her a Countess if she succeeded in her mission. That alone should be reason enough to stay. She drew herself up and smiled harder.

It was at that moment the footman announced a “Mr. Bernard.” Mademoiselle Girard merely glanced briefly toward the door as if the arrival of the man she hunted was of little moment before declaring herself faint from the heat. A hundred arms, or so it seemed, were proffered and she was soon swept off to an elegant, uncomfortable chair from which she could observe her quarry. The youngest of her admirers was dispatched to fetch her wine and exited with resigned grace.

Bernard had not seen her, which was as well since he might have recognized her from the Court. But he spared none of the young ladies present a glance on his way across the room to the Governor’s side. Sir Henry Morgan, Governor of His Majesty’s colony of Jamaica, seemed inclined to listen to the gentleman. Certainly their faces were serious enough to suggest grave matters, and that alone was unusual on such an occasion.

“La!” Celeste murmured. “It is so hot in here. Perhaps you would be so kind as to escort me?” She gestured toward the open balcony at Morgan’s back and fluttered her lids at the young man who had just returned with her wine. His youthful cheeks flushed crimson but he was fast enough to offer his hand to assist her in standing, moving with a fencer’s grace before the others could reach out.

He was swift enough too in sweeping her over the floor and out into the relative cool of the deserted night air before anyone could follow. Celeste gave him a speculative glance. There was not even the beginning of a beard on his tanned cheeks. But his expression, now that suggested years of a certain kind of experience she would not have expected in one so young. Had she miscalculated? She had thought him easily handled. Celeste frowned a moment, slightly puzzled.

The young man murmured in near perfect court French, “How lovely you are tonight, mademoiselle.” He reached out and twirled one of her blonde curls around his finger, barely grazing the bare skin of her neck.

Celeste shivered despite herself. He moved his hand up and traced the delicate shell of her ear. “And such perfect ears, straining so very hard to hear the English Governor’s words. What do they talk about inside, do you think, the former pirate and the French gentleman in the somber clothes?”

He had leaned over so that his lips were nearly at her ear and this time, Celeste did start. She stared up at him in the moonlight, her eyes narrowed in suspicion. “Who are you?”

“Another lost soul from France, my lady.” The words were said with a smile that sent Celeste’s fingers searching for the small dagger hidden in her skirts, moving as if of their own accord. The young man caught her hand and pressed it to his lips. “Surely so beautiful a flower has nothing to fear from a boy like me?”

Now Celeste did stare. What was it about this lad? He had a pretty face, did the young man, with a long, narrow jaw, brown eyes, and a thin patrician nose, all beneath a shock of dark red hair. She dropped her gaze to his beardless chin and from there, below. “Mon dieu! You’re a woman!” She gasped at last.

The young man went on holding her hand. “Captain Jacquotte Delahaye, at your service.”

“The pir--!” Jacquotte’s fingers were on her lips now, silencing her startled exclamation. Celeste could feel her eyes go round, like a girl scarcely out of the nursery and she despised herself for it. With an effort, she squelched her awe.

Even though she stood in the moonlight with the celebrated French pirate queen, steps away, an Englishman plotted against the French King. There was no time for this nonsense. Her expression must have changed because the pirate pulled her fingers away, so speedily she must have feared being bitten.

Celeste pushed her companion back toward the curtain, a low, flirtatious laugh rising from her lips. “Oh sir,” she said in an excellent English accent, “You are too forward!”

Delahaye smiled and looked down as if she was the only maiden in the world. The Governor and Mr. Bernard continued their discourse. Now and then, a word, a phrase, drifted out on the night breeze. There was mention of a treasure, then something else she could not hear.

A moment later, though, Morgan’s voice boomed out, “You have done well, Sir. Come to my residence tomorrow and we will discuss payment.” The Governor slapped his guest on the shoulder, clearly to the other man’s distaste, and turned to survey the room. His expression was shrewd as he glanced around, pausing a moment on the two figures on the balcony.

“Don’t bite me, chéri,” Jacquotte murmured and Celeste found herself being thoroughly kissed. She pushed vainly against the pirate’s muscular arms and shoulders but could do nothing against being held tight in the other woman’s grasp. It was only for a moment, but it was enough to her gasping for air and filled with strange sensations. Delahaye released her. “Now behave as you would with any young man who took such liberties.”

Celeste slapped her hard. “How dare you, sir! I am not to be used in this way.” She shoved Jacquotte so that she stumbled back, releasing her grip. Then she stormed into the ballroom in time to catch Governor Morgan’s eye.

The old pirate leered and offered his arm. “And how could any man resist stealing a kiss from such beauty? Permit me, dear lady. I shall keep you safe at my side until you desire otherwise. You are newly come from England to visit Lady Aston, are you not?”

Celeste noticed that Monsieur Bernard had vanished as suddenly as he had come. She simpered and blushed under the Governor’s eye, summoning nearly forgotten skills. The blush was long out of fashion in Paris, but here it seemed required. “Yes, my Lord. Jamaica is such a beautiful island!”

Morgan smiled down at her, while his black eyes caressed her décolletage so that if she had been the maid she pretended to be, she might have feared for her virtue. As it was, she thought of her mission, and not a little of Jacquotte Delahaye. With the former in mind, she prattled on about the tropics and about her fear of pirates, now assuaged by the presence of such a stalwart representative of His Majesty’s government.

At the mention of pirates, Morgan’s face changed from flirtatious to nearly unreadable. Celeste found herself transferred inelegantly from the Governor’s arm to that of Lady Aston, who approached at his gesture. “He’s very sensitive on that topic, my dear,” Lady Aston murmured. Celeste very nearly rolled her eyes. Lady Aston was charming, of course, but sometimes it was simply not enough. At that moment, their progress toward the door was blocked by a familiar figure.

“My apologies, Lady Aston. I felt I must beg forgiveness from your young charge.” Jacquotte Delahaye had a sweeping bow, graceful and powerful. “I was overcome by the moonlight, beautiful lady. Please forgive me. Say that I may call tomorrow.”

Celeste drew back, her heart pounding. Whatever the pirate wanted here, it could have nothing to do with her. Unless she too sought the Spanish gold that the King of France needed. There was only one way to find out. Celeste fluttered her fan once more as if undecided. Lady Aston sounded puzzled when she answered for them both, “I’m not sure what you mean, sir.”

“Very well. You may call tomorrow afternoon.” Celeste closed her fan with a snap and tugged Lady Aston forward. Delahaye stepped back and they made their escape.

Lady Aston looked askance as they entered her coach. “Have you acquired an admirer, my dear?”

“Something even better.” Celeste’s smile was more genuine than it had been all evening, but not another word would she say on the topic. Instead she steered her friend into the safer waters of gossip and fashion. Such things were far less likely to place her neck in a noose than knowing the secrets of the King of France’s best spy in the Caribbean.

Celeste’s mind was whirling when she reached her room, and once her maid had unlaced her and helped her into her nightdress, she found herself dismissed. Her employer paced the room as she left, absently running a brush through her blonde curls.

Morgan and his mysterious visitor had to have been speaking about the missing treasure of Jean Fleury. Rumors that the privateer’s gold had finally been discovered had drifted as far as Versailles and the King’s ear. And here she was, sent to find the truth. She pulled her orders and papers from their hiding place and spread them on the desk. But she wasn’t ready to sit down and read through them again, not yet.

She had managed to gain enough information in the last fortnight to make it clear that the stories were true, but as to the who and the where of it, that was more challenging. For that, she would need something more than her disguise as an English near-innocent come to visit her aunt in Jamaica. She opened the wardrobe and reached into its darkest recesses. There was a click, as of a tiny secret lock, then she emerged carrying a bundle of clothes, a pair of boots and a sheathed sword.

The curtains at the open window fluttered, their white length startling her. But that was nothing in comparison to her response to the appearance of Jacquotte Delahaye in their midst. “Good evening, mademoiselle. I prefer to set my own hours for visiting.” The pirate smiled.

Celeste threw the clothes and boots aside and drew the sword with the ease of long practice. She held the length of her rapier between herself and her unexpected visitor. “What are you doing here?”

The pirate looked amused. “I’m accustomed to young ladies shrieking for their maids when I appear in their rooms. This is something new. But then, you’re not what you seem, are you, mademoiselle?”

“Do you make a habit of sneaking into ladies’ bedrooms at night then? I though pirates sailed on ships and robbed on the high seas.” Inwardly, Celeste cursed Delahaye’s timing. A few more minutes and she would have been dressed for fighting. Now, her nightdress would slow her down. But she did not let the pirate see that thought and the hand that held the rapier was rock steady.

“Only very unusual young ladies.” Delahaye nodded toward the sword. “And you can handle a blade. I can see as much from your stance. So now that I know that, put up your sword, lass. I’ve come to talk.”

“Talk fast then. My aunt often comes to my room to say good night.”

Delahaye moved like a striking cat, knocking aside Celeste’s blade with a pillow she seized on her way to the door. With a single gesture, she slid the bolt home and leaned against it. “Now we won’t be disturbed.” She looked around the room, ignoring Celeste’s muffled curse as she rubbed her wrist. “Ah. Just what I was looking for.” She snatched the papers from the writing desk and drew her pistol, pointing it at Celeste.

Celeste saw her death in its round mouth for a span of breaths. But Delahaye did not pull the trigger. Instead, she rifled through the papers as if looking for something specific. Celeste lunged forward, hoping to catch her off guard.

Delahaye spun away, her expression annoyed. She leveled the pistol at Celeste’s head and spoke in a tone that did not allow for disagreement. “Do that again, mademoiselle, and I’ll be forced to damage a work of art.”

Then she seemed to find what she was seeking. She studied the document with a satisfied expression that froze Celeste in place, waiting for what she could not prevent. She read aloud, “It is in the service of the King of France that the bearer of this letter has done what she has done.” Delahaye’s smile turned wicked. “You have a landsman’s letter of marque, mademoiselle. Perhaps you might tell me why.”

The pirate’s dark eyes were cold and fierce and the easy lie she had been about to tell caught in Celeste’s throat. What would Delahaye believe? “I’ll make it simple for you then. You are a Frenchwoman pretending to be English and you can handle a sword. I believe you to be either a spy or an assassin. Now what has Sir Henry Morgan got that your King Louis wants?”

“He is your King as well as mine,” Celeste retorted, her tone ice in the humid air. “Now put my papers back. I would dislike to add you to my list of enemies, Mon—Maidemoiselle.” She stumbled over the words, wincing at her own clumsiness.

Jacquotte Delahaye laughed softly. “Madame, if you will. But alas, widowed.”

“Widowed? Never mind.” Celeste raised her free hand. “I have no wish to know the fate of Monsieur Delahaye. I do, however, want my papers and to be free of your presence.”

“And thus I am dismissed.” Jacquotte crossed the room, pistol still pointed steadily at Celeste. She seated herself on the edge of the bed. “Sit,” she gestured at the room’s only chair.

Celeste gritted her teeth. “I prefer to stand.”

“Indeed.” Jacquotte shrugged. “Well, mademoiselle, I have speculated on your purpose here in Jamaica and you have not denied my theories.”

“Do you really believe me an assassin?”

“I imagine that I would even now be fighting for my life if that were the case.” Jacquotte’s eyes gleamed with mockery. “I suspect that we both seek the same goal, however: Jean Fleury’s gold. Though it would seem we have a different purpose for its use.”

Celeste snorted. “The taverns of Port Royal are hardly a noble purpose.”

“In comparison to gold-plating the asses of some aristocrats at Versailles? No, I suppose not. In any case, I desire more than that and you, mademoiselle, may help me achieve what I desire. I am willing to divide the gold equally in return for your help.”

“And if I don’t?” It was an extraordinary offer. Extraordinary and ridiculous. Why should this woman think she would accept it?

“I could shoot you now,” Jacquotte responded, her expression thoughtful. “But that would rouse the household and be something of a waste. No, mademoiselle, refuse my generosity and I will foil your plans at every turn. Consider, if you will, that I have a ship and men at my command. You have only your wits and considerable charms. How will you liberate the gold? What will you do with it then?”

Celeste studied the pirate before answering. It seemed wisest to appear as foolish as the other woman thought her. She mustered a look of confusion. “I can call upon any French ship in these waters.”

“And as you have been so eager to declare me a subject of the King of France, allow me to offer my ship as the one you call upon. Provided, of course, that you accede to my wishes.”

“Which I know nothing of. Do you plan to enlighten me?”

“It will be nothing beyond your powers, I can assure you. Now I have other business to attend to and must take my leave.” Jacquotte stood, but seemed to waiting for a response.

Celeste frowned as if considering her options. Finally, she summoned a reluctant, “Very well.”

“Excellent. Then I will take my leave, Celeste, if I may call you so, and leave you to your dreams.” The pirate vanished out the window before Celeste was able to respond.

She dashed over and looked out. Delahaye was clambering down the wall below, ending with a short leap into the bushes. She was gone from view within moments, leaving her audience shivering behind her. Celeste closed the window before she turned back to the room, refusing to wonder what the pirate might want from her.

Within moments, she was dressed in her man’s garb. She bucked her rapier to her belt, slid daggers into the sheaths in the top of her boots and bound up her hair so it would tuck up beneath her hat. The heavy vest that she added next would leave her panting if she had to run but would cover her breasts enough so that she might pass as a man, if not examined too closely. She had no intention of letting anyone get close enough to notice.

Last, she caught up her most important papers and slipped them into a pouch that hung around her neck and tucked it beneath her shirt. They would be safer there, she suspected if Delahaye could enter her room so easily.

Then she grabbed the rope she had stored in with her clothes and opened the window once more. After tying it to her bedpost, she began her own descent to the ground below. Miraculously, it seemed as if Lady Aston’s household slept through it all. She viewed the darkened windows above her with relief. Lady Aston had been so kind, had asked so few questions of the daughter of her former school friend, that to distress her seemed an unkindness.

Celeste slipped through the garden like a shadow, silently traversing her way through the old gate in the far wall and into the quiet streets beyond. The streets of Port Royal were as close to silent as they ever were. Celeste could hear drunken shouts in the distance as she slipped quietly through the darkened streets. She made a right turn, then two lefts and she saw torches flickering feebly before an old inn. Faded letters pronounced it to be “The Sea Dog.”

She stepped forward with a quick glance to either side to verify that she was not followed. Then she loosened her sword in its scabbard and opened the tavern door with a manly swagger. Still, her heart raced as she looked around the common room, prepared as she could be, for anything.

Fortunately, the lateness of the hour ensured that there were few within still sober enough to sit upright. Men slept on the benches or head down on the tables. A whore snored in a corner near the unlit fireplace. Only one or two heads turned to watch her, then looked away when they saw her sword. The landlord gave her a hard stare, then jerked his head toward a closed door in the darkened recesses under the stairs when she gave him a two-fingered salute. She nodded and rapped door three times.

Responding to a sound from within, she entered. The two men at the table stood, one after the other. The taller one swept his plumed hat from his head and would have bowed had he not been stopped by a preemptory gesture. A few moments of muted conversation followed and candlelight glinted on a handful of gold coins as they changed hands. Then all three left the room, and the tall man tossed the landlord a coin.

Once outside, they separated, each moving in a different direction. Celeste directed her steps back toward Lady Aston’s and bed. Perhaps weariness made her careless, or so she thought afterwards. By then it was too late. Before she knew she was under attack, shadowy figures forced a foul-smelling sack over her head and knocked her unconscious.

When she awoke, she was bound hand and foot, but at least the sack was gone. Her head hurt like the very Devil, and she could feel the sea’s motion somewhere under the table she was tied to. The room was nearly dark, for which she was grateful. She forced herself to test her limbs, then to try her bonds. Both were solid but the movements hurt enough to tear a groan from her throat.

As if it was a signal, a huge man opened the door and stepped inside. He grinned down at her, his smile exposing a few missing teeth. His beard was filthy and his person made even less appealing by the stench that rolled off him: rum and long unwashed flesh. Celeste yanked frantically at her bonds, nearly breaking her wrists in her struggles. She had sworn that no man would harm her again; two deaths were testament to that vow. But now she was helpless.

The man laughed and stepped closer, meaty hands descending on her bound legs. His fingers dug into her flesh through her breeches. “You’re a pretty piece, aren’t you? Think I’ll have me a bit of fun while the Captain’s not about.” He leered as his hands slid higher and Celeste cursed him with every oath in her vocabulary.

The door opened behind him with a sharp bang, making them both jump, and she could see another man in the doorway. Silently, she vowed that she would live to kill them all, every one of them. That determination leant steel to her spine and a layer of ice to calm her panic. She had only to endure, wait for her chance and be ready.

A sharp blow from behind staggered the brute and he fell away, spinning around with his knife drawn. He was snarling now, knife held at the ready, knees in a fighter’s couch. But there was a sword’s point hovering before his eyes now and at the other end, the blazing eyes of Jacquotte Delahaye.

Celeste wondered if Delahaye was swordsman enough to defeat an opponent nearly twice her size. She worked even harder at loosening her bonds; after all even if Delahaye won this unequal combat, there was no guarantee that Celeste would not be next.

The clash of blades tore her from her thoughts. The man lunged at Jacquotte and she had turned his blade easily. The knife blade flashed as he matched her movements, looking for a chance to get past her rapier. But her guard held. “Give it up, Poole,” she said in heavily accented English. “Your pigsticker is no match for my steel.”

He growled something at her and Celeste could see his free hand dart out of sight, searching for something to hurl. “Watch out!” She exclaimed as his hand closed on a loose bolt.

Jacquotte dodged as it sailed through the air, then ducked under his arm and drove her sword into his shoulder. He bellowed in pain as she yanked the blade free and pressed the tip against his throat. The knife fell to the floor with a clatter and Celeste smiled as blood began to stain his already filthy coat.

Delahaye raised one dark eyebrow. “Is this done?” Poole nodded. “Disobey me again and I’ll cut your balls off and stuff them down your throat.” She stepped aside and he sidled past her, clearly reluctant to turn his back until he could stumble away across the deck.

“Now, as to you, mademoiselle, my apologies for your treatment. I anticipated that you might prove...reluctant to cooperate if you had too much time to think.” Jacquotte smiled and it sent shivers down Celeste’s spine. “But I suppose my point is made.” With a few deft turns of her wrist, she severed the ropes that bound her captive to the table.

Celeste sat up awkwardly, hands still bound. She held them out, “What must I exchange for my freedom?”

Jacquotte’s smile changed a bit, her lips twisting in a slight grimace. “So simple? I must wonder. But here it is, mademoiselle. I want a letter of my own, one that says that I do what must be done in the service of France. I would like to return home a welcome hero, not a despised pirate. This is my price.” Her back straightened and she looked past Celeste as she spoke, as if she was seeing into the future she described.

“A letter of marque, making you a privateer for the King?” Celeste spoke slowly, trying to think. It surprised her that Delahaye would trade the complete freedom of the seas to pillage for France but if the great Henry Morgan could turn governor, anything was possible. “And for this, you will help me to capture all of Fleury’s treasure for France?”

“Let us say much of it. I have expenses.” Jacquotte sheathed her sword and gestured expansively at the cabin walls.

“Rob more Spanish and English dogs then, and leave the King of France his gold.” Celeste growled. “Fleury would have done so had he lived.”

“Would he? God save us all from honorable pirates,” Jacquotte laughed. “Now, Mademoiselle Celeste, I will free you if I have your word that you will not attempt to slaughter the crew or myself.”

“It is much to ask.” She could feel the boat’s motion changing, as if sails were being brought in. “Where are we?”

“We are following our mysterious countryman, he who is such a good friend of Monsieur the Governor.” Jacquotte gestured toward the open door. “Do you wish to see if we have been successful at finding his hiding place?”

Celeste held out her bound hands in mute answer, nodding to the question in Jacquotte’s eyes. Her wrists were free a moment later and she was staggering to her feet on legs not yet seaworthy. Jacquotte caught her arm and guided her forward to the door, and from there across the deck.

Despite her stumbling, Celeste was able to look around the ship as they moved toward the prow. It had been a flagship, probably English, from the build, before it turned pirate. The black flag was folded and stowed on deck, she noticed, while the ship flew merchant colors from Portugal.

But the men were as she expected: a rainbow-hued assortment of cutthroats, murderers and common sailors. Celeste glanced from one scarred or tattooed hard-eyed face to another and wondered what kind of woman could survive their company.

Jacquotte glanced at her and smiled. “I’m their Captain and they know I’m fair. Everyone gets an even split of the spoils. It’s enough for most of them. The rest know I can kill them.”

Celeste felt her lips curl into a reluctant smile. It was difficult not to feel admiration for this pirate. She only hoped that she would not be forced to kill her.

A motion out on the water caught her attention: some distance away, a small boat was sailing into what appeared to be a wall of rock. “Look!” The word fell from her lips before she realized that Jacquotte had released her arm and was now training a spyglass on the ship. “Are we going in after him?” She demanded, her voice full of newfound eagerness for the hunt.

Jacquotte did not lower the glass. “No, chéri. We would tear the bottom from my ship and I will not permit that to happen. We will wait here for him to sail back out and we will capture him then.”

Celeste let out a sigh as if deeply disappointed. In reality, she had ordered her men to find and hunt this dog Bernard when they left the tavern. If all had gone well, one of them should be aboard that vessel. The other... well, time would tell, she hoped.

Jacquotte glanced briefly at her, then ordered one of the pirates to bring up a short stool. “Here,” she nudged it with her foot. “Sit and keep watch up here. We’ll be preparing the ship.” With that, she turned over the glass and nearly flew down the stairs to the deck. Celeste watched her, bemused as she strode the length of the deck, barking orders and gesturing at the rigging and the guns.

Celeste permitted her mind to drift, watching the sea and the rocks for a time, while she dreamt of home. But then she saw the pale outline of a ship’s sales against the rock walls. “They’re coming!” She called over her shoulder, hoping her voice would carry above the mayhem on the deck, but no further.

Several footsteps raced up the stairs behind her and a large hand plucked the spyglass away. Celeste glared up at a skinny man with a scar running the length of his long face. Jacquotte threw her an amused glance and she staggered to her feet, determined not to be caught off guard.

“Right enough,” the fellow grunted as he handed the glass to Jacquotte and gave Celeste an approving nod.

Celeste took a moment to glance at the deck below them and was astonished to discover that the cannon were all hidden below painted clothes. Everything was the color of the deck or of the sea beyond, so the guns might well be invisible from a distance. But why go through so much trouble for one small ship?

She looked up at Jacquotte for answers and noticed that the glass was pointed toward the distant cape now. If she squinted against the sun, she could just make out the sails of several large vessels. “Henry Morgan’s ships, awaiting delivery of Fleury’s gold.” Jacquotte murmured as if she knew Celeste’s thoughts. “But we’ll hail them first.”

The pirate captain bared her teeth in a species of ferocious grin and Celeste could not suppress a shudder. If the pirates miscalculated, they would be attacked by their quarry and Morgan at the same time. That way lay near certain death.

Celeste could not stop herself from glancing away toward the other end of the island. Were there white sails visible in that direction as well? She prayed that it was so. Unless the French ship was in place, she might well have to turn pirate herself.

When she turned back, the rock wall and Bernard’s ship were much closer than she expected. There was a brisk exchange in Spanish above her head, the words too fast for her to follow. Then she found herself being towed down to the deck and back to the cabin by the thin man.

“Captain’s orders, dulce. No landsmen on deck to get underfoot.” He grinned down at her with blackened teeth and gave her an affectionate slap on the buttocks as he crammed her into the cabin where she’d been held earlier. A key turned in the lock as she grabbed for the knob and she cursed Delahaye and her crew heartily.

A few moments later, the ship listed sharply, as if it had struck a rock. Celeste fell to the floor and cursed even harder. She had not thought Delahaye so foolish as to sail too near the shore. From outside, she could hear voices bellowing, then the sound of a ship being hailed. She glanced out the porthole and noted a taut chain that dragged something through the water.

More shouts from outside, then a moment of silence broken by a barked order. The chain clanked sharply as it was suddenly released. The ship rocked back upright and one cannon, then three suddenly loosed their load. Celeste covered her ears and braced for return fire.

When none came, she reached into her belt and found a thin, narrow piece of metal. She bent it first one way, then the next and inserted it into the lock. She kept trying until the lock turned and she was able to crack the door enough to see out on deck. The other ship was well within range now and it was clear that it had lost sails and part of its mast to the pirates’ cannon.

Celeste squinted through the smoke as the ships moved closer. A grappling iron thrown across fell short but she knew it would connect the next time. Smoke was rising from the other ship’s hold.

And on the pirate deck, Delahaye was shouting her orders. She carried a pistol in her hand and there was a light in her eyes like that of a woman in love. Celeste looked out to each end of the island, one after the other, checking on Morgan’s ships as much as her own. The sails were closer now. If they were to take the gold and get away from Morgan, they must do so now.

A hail came from the listing ship. Bernard stood at the prow, hands cupped around his mouth to make his voice carry. Delahaye yelled something back but the wind turned it and shredded it before Celeste could hear it. She suspected that he intended only to buy time until Morgan’s ships arrived but it was clear that he would not succeed.

There was a crunch of wood as first one grappling iron, then another found its purchase. Pirates began to wiggle or swing across. A shot from a musket felled one into the water, then the first of them were over. Celeste could hear the clash of blades as she eased her way out of the cabin.

No one seemed to notice as she made her way around the deck. All eyes were trained on their quarry or on Morgan’s ships. It was child’s play to reach the ropes that bound the ships together, less so to crawl across. As she hung between ships, it gave her a moment’s pause to notice that Delehaye’s ship was called

The Lioness while Monsieur Bernard’s was

The Antelope. Had she not been so terrified of falling into the churning waves below, she might have laughed.

As it was, she hung from the swaying rope and hoped that her legs would hold her if her bleeding hands finally released the coarse salt-laden twine. Perhaps she did not need to be a Countess after all. If she disappeared into the jungles of this New World, who would ever know that she had failed in her duty?

Finally, she reached

The Antelope’s side and managed to ease her trembling body over the rail to collapse on the deck. Once there, a few of the sailors still fought the pirates. Bernard was in the thick of it, his sword flashing as he repelled as many of Delahaye’s crew as he could.

Celeste saw one of the pirates glance her way and turn to alert Jacquotte whose sword even now met Bernard’s. She gathered herself for an awkward dash across the smoking deck before diving into the open hold. She landed with a roll that brought her up short against something hard.

She unrolled with a curse and fumbled through the smoke and the darkness for the flint she’d hidden in her leather vest. There must be something down here that she could safely light as a torch. It was then that her nearly deafened ears heard the tell tale crackle of flames coming from somewhere above her. Her heart sank; the French ship would not get here in time. This ship would sink and she would die and vanish along with the gold.

But there was no time to give her fears free rein. The flames would give her a bit of light to see by, as long as she was fast and careful. With a mighty effort, she pulled herself back from the brink of despair and began to look through the objects in the hold. The gold must be here somewhere.

There was a shout from the deck and a figure hurtled down into the hold, landing next to her. She and Monsieur Bernard stared at each other in startled recognition. “You!” He finally hissed. “Louis’ little spy! This all your fault!”

“Traitor!” Celeste bellowed.

He swung his sword as she spoke, a great sweep of the blade that might have taken Celeste’s head from her shoulders if she hadn’t ducked. She felt for her own sword, forgetting that Delahaye’s crew had taken it when they kidnapped her.

Bernard’s blade passed perilously close to her face and she threw herself backward in an acrobat’s roll. When she uncoiled, her hands closed on a loose iron hook, heavy but not so much that she couldn’t lift it. Bernard was stumbling toward her now, trying to see in the dim light and the smoke.

She hefted her weapon and swung it, forcing him back for a moment. He brought up his sword and she caught the blade on the hook. For a moment, they wrestled and she held him off. But he was stronger than she was and the blade was coming free.

Using every bit of force she possessed, she kneed him sharply between the legs and he doubled over. But he held onto his blade as she stumbled back ward.

“Here.” Jacquotte’s voice rang out unexpectedly over the noise of the fire. She tossed her cutlass hilt first and Celeste caught it, though barely.

It was nearly as heavy as the hook but she managed to raise it in time to meet Bernard’s blade. She could see his face now, teeth set in a snarl as sweat and blood ran down his cheeks. A quick glance upward told her that the flames were spreading: not much time left. She dropped down into a crouch so that he stumbled and shoved him backward while he was still off balance.

Then she swung Jacquotte’s sword with all her might, slashing her way across Bernard’s belly. He screamed and clutched at himself with his free hand, but still managed to deal Celeste a savage blow with his own blade, cutting her shoulder before she managed to force his blade away. “Slash up! Up!” Jacquotte bellowed from the dimness.

For a moment, Celeste staggered, unable to grasp what the other wanted her to do. Then she turned the blade and sliced Bernard open. He fell with another scream and a liquid thump. Celeste turned away, trying not to be sick. She had never killed like this before.

It almost made her forget the gold. “I’ll take that.” Jacquotte plucked the blade from her nerveless fingers. “You did well, chéri. Now help me find the gold before this tub sinks.”

That brought Celeste back to herself. Moments of frantic searching later Jacquotte stumbled across a locked door in the back of the hold. A single ball from her pistol opened it for them and there they found the chests they sought. Celeste ran a wondering hand through a sea of gold coins, marveling at the wealth before her.

Jacquotte’s crew found them then. “Captain!” The mate’s eyes were wide. “This tub is spent and both Morgan’s men and the

Neptune, flying the colors of France, are nearly upon us.”

Jacquotte stared at Celeste. “Your pistol, Villiers.” She took it from his hand and pointed it at Celeste. “Now take two of these chests over to

The Lioness.” Celeste jumped up to protest, but stopped at the look on the pirate’s face. “You sent for a ship of the line, mademoiselle. Very clever. Now you shall wait here for them to rescue you.”

“You could take me with you. You’ll outrun Morgan or maybe even outfight him.”

“Best to run. Morgan’s ships carry more guns. Now, as regards taking you with me...”

Jacquotte caught her up then, hard arms holding her still while steel fingers trapped her jaw. Then she kissed Celeste, her lips and tongue so surprisingly tender that Celeste found herself surrendering to them.

She wrapped her arms around Jacquotte’s neck and kissed her back until it felt as if she might lose herself completely. It was enough to ignore the little voice in her head that screamed that she was committing a mortal sin. What was one more amongst so many? The bearer of the letter had done what she had done.

Celeste gasped as the pirate let her ago. “Until next we meet, chéri. Perhaps I will see you at Versailles.” Jacquotte moved like a cat, slipping over the side of the wounded ship before Celeste could utter a word. Celeste watched as she swung across on the grappling iron’s rope. The pirate ship was cut loose in a span of breaths and began to pull away as the wind filled its sails. Celeste glanced to either side at the ships bearing down on them. Already Morgan’s ships were turning to chase the pirates, and Celeste’s man had emerged from somewhere to hail

The Neptune.

Jacquotte stood at the prow of

The Lioness, Celeste’s letter of carte blanche from the King fluttering in her hands. “The bearer of this letter had done what she has done in the service of France,” she bellowed over the cheers of her crew. Then she blew Celeste a kiss as the wind caught her ship’s sails, leaving Morgan to wallow in its wake.

Celeste pounded her hand on the railing in frustration. When had Jacquotte stolen her letter? And she had only a third of Fleury’s gold to show for her efforts. How could she lose so badly? Unconsciously, her fingers touched her lips. She would find a way to recover what was hers; of that, Jacquotte Delahaye might be quite sure.

* * * Catherine Lundoff is the two-time Goldie Award-winning author of

Night’s Kiss (Lethe Press, 2009) and

Crave: Tales of Lust, Love and Longing (Lethe Press, 2007) as well as over 70 published stories. She is also the editor of

Haunted Hearths and Sapphic Shades: Lesbian Ghost Stories (Lethe Press, 2008) and is the co-editor, with JoSelle Vanderhooft, of

Hellebore and Rue: Tales of Queer Women and Magic (Drollerie Press, 2010). In her other lives, she's a professional computer geek and teaches writing classes at The Loft Literary Center. Website: www.visi.com/~clundoff

What do you think is the attraction of the historical fiction genre?I've always been a big fan of historical fiction. As a kid, I read a huge amount of Alexander Dumas (father, not son), Howard Pyle, Robert Louis Stevenson, Baroness Orczy and Raphael Sabatini. I still enjoy them all, though now I tend toward Jeffrey Farnol and Georgette Heyer. As a genre, it has the charm of being based on real events without the burden of coming off as rather dry. I'm often fascinated by the differences I see in what is presented as established history and what actually happened. The latter is often even much livelier than the fiction, but the fiction is usually better written.